Last month, we discussed the relationship between the monastic charism (often colloquially called spirituality) and the general, Gospel spirituality. We saw that the end of all monastic practices is nothing other than a concentrated form of the Christian life. In the history of the Church, monasticism was never viewed as something extraordinary or particular. Men and women enter the enclosure to seek God according to the Gospel principles in a more deliberate, focused manner.

The essence of monastic life and its practices are attainable by laymen in appropriate proportion to their state. Unlike other religious orders that might require specific gifts in order for a person to thrive, the monastic charism demands only a baptized, immortal soul and the will to seek God. This month, as we continue our journey to discover how the liturgy is the premier source of formation in spiritual childhood, we turn at last, specifically, to the liturgy. Since the monastic practices are applicable to all Christians in due proportion, their premier obligation and most sacred work, liturgical prayer, is here examined.

Prayer, Life

“Prayer is man’s richest boon. It is his light, his nourishment, and his very life.”1 These are the opening words of Dom Gueranger’s “General Preface” to The Liturgical Year. Without reading another sentence, the argument of Gueranger is clear. By beginning his 15-volume commentary on the Liturgical Year with the declaration that “prayer is man’s richest boon,” the reader is assured that Gueranger will argue that the liturgy is man’s richest boon. Liturgy is the deepest and most intimate prayer a soul can experience. Gueranger was certainly not the first author to comment upon the liturgy, but he is seen to be the father of the modern, liturgical movement.2 In the 150 years since Gueranger, the Church has seen a renewal in the desire for the faithful to understand and participate in the liturgy. The exhortations grew from the ground up as well as from the top down.

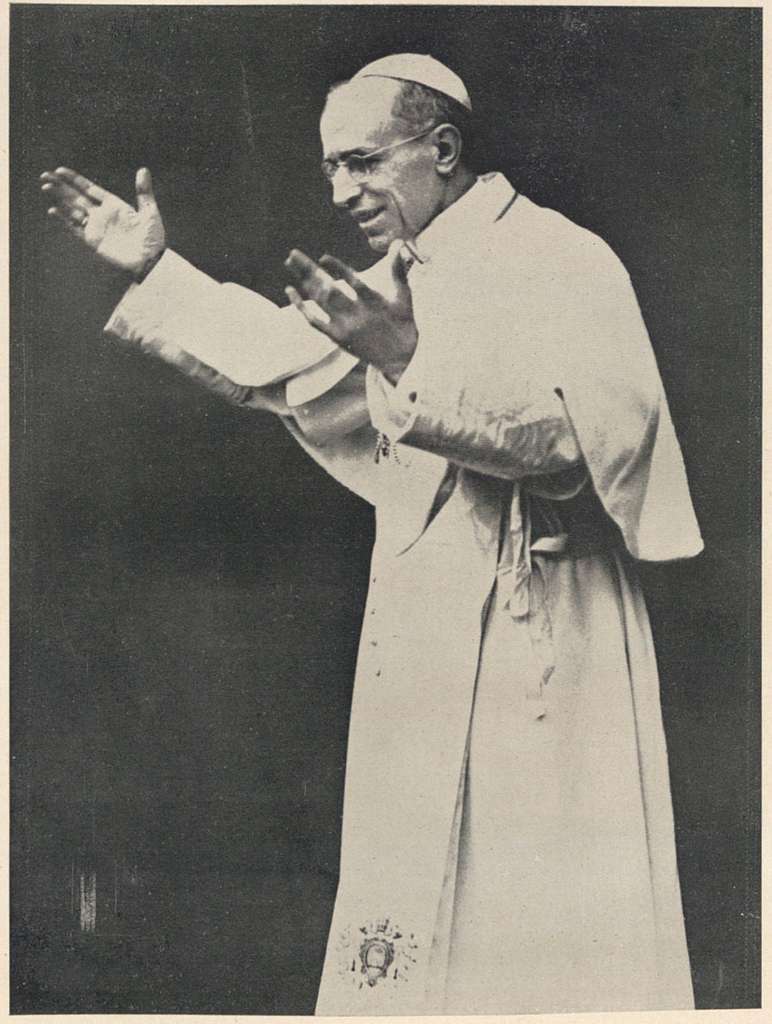

No conflict exists between public prayer and prayers in private, between morality and contemplation, between the ascetical life and devotion to the liturgy. –Pope Piux XII, Mediator Dei

The proponents of the Liturgical Movement believed that the liturgy of the Church is the most sacred and intimate heirloom of each individual Christian. It is true that the liturgy is “the public worship which our Redeemer as Head of the Church renders to the Father, as well as the worship which the community of the faithful renders to its Founder, and through Him to the heavenly Father. It is, in short, the worship rendered by the Mystical Body of Christ in the entirety of its Head and members.”3 Yet, the public nature of the liturgy does not detract from the intimacy of personal prayer: “Let not then the soul, the bride of Christ, that is possessed with a love of prayer, be afraid that her thirst cannot be quenched by these rich streams of the liturgy…. So true is it, that for the contemplative soul’s liturgical prayer is both the principle and the consequence of the visits they receive from God. But in nothing is the excellency of the liturgy so apparent, as in its being milk for children, and solid food for the strong; thus resembling the miraculous bread of the desert, and taking every kind of taste according to the different dispositions of those who eat.”4

The reality is far from the idea that private and liturgical prayer are in opposition—one that souls desire and one that they begrudgingly participate in: “no conflict exists between public prayer and prayers in private, between morality and contemplation, between the ascetical life and devotion to the liturgy.”5 The 20th-century theologian Louis Bouyer also discusses the connection between the two forms of prayer. After previously discussing lectio divina as the epitome of private prayer, he writes, “Lectio and psalmody [liturgical prayer] are, as it were, [the soul] breathing in and out, the diastole and systole of the heart created in him anew by the Spirit.”6 In both forms of prayer, the Word of God is central. The inspired Scriptures form the heart. That is because “the Spirit helps us in our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us with sighs too deep for words” (Romans 8:26).

–Image Source: AB/Wikimedia

Thus, the Holy Spirit is the author of both forms of prayer, and they are perfectly complementary. Private prayer, especially lectio divina, is the arena wherein the soul inhales the Spirit of God. The soul breathes in the Holy Scriptures, meditates on them, listens to the whispers of God, and integrates them. In response to this inhalation, the soul’s natural and inevitable response is exhalation—the aspiration of God’s praise in the liturgy. Lectio divina teaches us to meditate on God’s Eternal Word so that we can, in imitation of the Blessed Virgin, “keep all these things, pondering them in our heart” (see Luke 2:19). The pondering, ruminative process leads to an eventual exclamation of Magnificat anima mea Dominum—“my soul magnifies the Lord” (Luke 1:46). While both forms of prayer are necessary for the spiritual life, liturgical prayer has primacy: “Unquestionably, liturgical prayer, being the public supplication of the illustrious Spouse of Jesus Christ, is superior in excellence to private prayers. But this superior worth does not at all imply contrast or incompatibility between these two kinds of prayer. For both merge harmoniously in the single spirit which animates them, ‘Christ is all and in all’ (c.f. 2 Cor. 6:1). Both tend to the same objective: until Christ be formed in us.”7 Such a primacy derives from its communal nature, the common good, and promulgation by the Bride of Christ.

Central and Essential

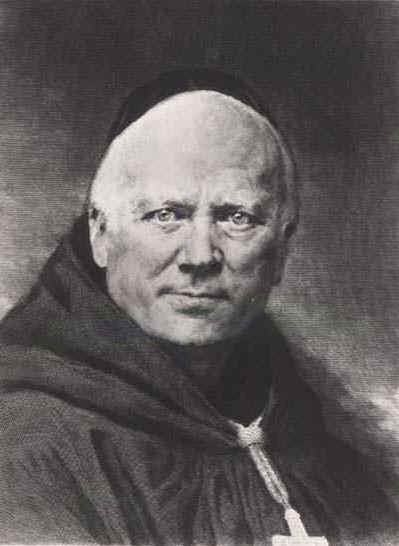

Taking the monastic life as a model once again, Dom Delatte (who as abbot of Solesmes from 1890-1921) sheds light on the primacy of the liturgy in the spiritual life. He writes: “having traced the main lines of the spiritual training of his disciples [ch. 1-7], St. Benedict now sets himself to organize liturgical and conventual prayer [ch. 8].”8 In the mind of the great monastic Legislator, liturgical prayer immediately follows the establishment of fundamental spiritual principles. Delatte continues, “He begins without any doctrinal introduction; but we may pause to ask ourselves what the Church and the old monastic legislators mean when, whether explicitly or not, they make the Divine Office [and Holy Sacrifice of the Mass] the central and essential work of the religious and contemplative life.”9 If it is the center of contemplative life, then it must also be the center of the Christian life.

Part of the liturgy’s centrality is its ability to unite all of creation. The liturgy reminds Christians that “the heavens are telling the glory of God; and the firmament proclaims his handiwork—caeli enarrant gloria Dei, and opera manuum ejus annuntiat firmamentum” (Psalm 19[18]:1). For well over a millennium the liturgy of the Church concluded Lauds—morning prayer—with the laudate Psalms.10 These Psalms call upon all of creation to unite in man’s adoration of God.

Praise the lord from the earth,

you sea monsters and all deeps,

fire and hail, snow and frost,

stormy wind fulfilling his command!

Mountains and all hills,

Fruit trees and all cedars!

Beasts and all cattle,

Creeping things and flying birds (Psalm 148:7-10)

Although non-rational creation cannot praise God in the same manner as men, their very natures testify to Him. For this reason, Paul declared to the Romans that “what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. Ever since the creation of the world his invisible nature, namely his eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made” (Romans 1:19-20). Paul further asserts that “the whole creation has been groaning in travail together until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait for adoption as sons, and the redemption of our bodies” (Romans 8:22-23).

We are, therefore, united to creation throughout the liturgy. We possess a rational and conscious nature while creation acts instinctively. Delatte asserts that “the whole of this vast creation speaks of God and obeys Him; it is a sweet song in His ears, a surpassing act of praise.”11 This proclamation of God’s praise is not a metaphor, a convenient image. As St. Paul said above, it is a deep reality and that those who fail to listen to their praise will be judged for their closed hearts. “Creation as a whole possesses in a true and special way a liturgical character. It resembles the divine life itself.”12 Yet, “formal glory is paid only by rational creatures, who alone are capable of appreciating objective glory and of tracing it back to its source. And only in this act do we get religion and liturgy.”13 Delatte goes so far as to say that man is “by his very nature an abridgement of the universe…his function is to collect the manifold voices of creation, as if all found their echo in his heart, as if he were the world’s consciousness.”14

Liturgy Defined

At this point, it is necessary to point out that the term liturgy encompasses more than just the external rites of the Church. According to David Fagerberg, professor emeritus of liturgical theology at the University of Notre Dame, “liturgy had a larger meaning when Christians borrowed it in the first place.”15 The Greek term Leitourgia is a combination of “work” (ergon) and “people” (laos) which means a work of the people. Specifically, “it denoted a work undertaken on behalf of the people. Public projects undertaken by an individual for the good of the community in areas such as education, entertainment or defense would be leitourgia.”16 Even this definition, however, is insufficient according to Alexander Schmemann. He describes leitourgia as producing a transformation among the people: “it meant an action by which a group of people become something corporately which they had not been as a mere collection of individuals—a whole greater than the sum of its parts.”17 Consequently, although certain men might have specific duties in the liturgical rites, the liturgy is not the property of these clerics. Nor is every member of the baptized able to exercise the ministry of the ordained.18 All members contribute to the body but each has a distinct role.19 As such, leitourgia is truly a communal act performed by the entire people.

Man is ‘by his very nature an abridgement of the universe…his function is to collect the manifold voices of creation, as if all found their echo in his heart, as if he were the world’s consciousness.’

–Dom Paul Delatte

Fagerberg points out that “when a verb is turned into a noun, the subject is usually the one who commits the action: A wrestler is one who wrestles, a builder is one who builds, and a plumber is one who plumbs.”20 Unfortunately, in much of theology and among the faithful, this understanding of every other verb-turned-noun is not applied to liturgy. On the contrary, “ordinarily, a liturgist is thought to be either the person who might want to read (or even write) a book like this one…that is, the person we ordinarily call ‘liturgist’ is the one who conducts classes, or conducts choirs.”21 A more authentic definition of liturgist would apply to those who do liturgy which, as was stated above, includes all Christians by virtue of their baptism. “Liturgists make up the Church, and the Church is made up of liturgists, and the word liturgist can be used as virtually synonymous with baptized or with laity to name the members of the mystical body of Christ.”22

The role of men and women as liturgists dates back to creation because “it is a doctrine that places man and woman, as microcosm, at the interface between the spiritual realm and material realm.”23 It is certain that “men and women were created as rational liturgists of the material world and placed at the apex of the systolic action in order to translate the praise of mute matter into speech and symbol.”24 Once again, the duty of man to speak on behalf of all creation is reaffirmed, and this duty has existed from the very beginning. Regrettably, “the fall was the forfeiture of our liturgical career. The economy of God, climaxing in Christ’s paschal mystery, was the means to restore it.”25 Fagerberg calls this natural state and duty of mankind a “cosmological priesthood” which “should not be confused with either the Church’s common priesthood of the laity, or the Church’s ministerial priesthood of the ordained. The latter two are for the healing of the first.”26

Thick and Thin

Now, the rites of the Church constitute an invaluable dimension of leitourgia, but we must always beware against a sort of rubricism—an attempt to restrict liturgy to simply the external celebration of instituted rites. Such adherence is necessary, of course, but adherence is not the essence nor the end of liturgy. To believe so is to restrict liturgy to what Fagerberg calls a “thin sense.” He says that: “Liturgy in its thin sense is an expression of how we see God; liturgy in its thick sense is an expression of how God sees us. Temple decorum and ritual protocol is liturgy only in its thin sense; in its thick sense, liturgy is theological and ascetical. Both senses are true and necessary, and one way of constructing the question would be to ask how thick liturgy is expressed in its ritual form (thin).”27 There is more to poetry than meter, and there is more to liturgy than rubrics. In other words, the liturgical rites are ordered towards a deeper, “thicker” participation in creation and adoration. The structures allow for and help achieve a greater purpose than themselves. Ultimately, however, it is true that “Christ is the premier liturgist, head of a body animated by the Holy Spirit, and so it is Christ’s work that the Church performs—which is to say the thick liturgy done by the Church must always and only be Christ’s liturgy, never its own.”28 Through Christ’s liturgy, preeminently in baptism, children of wrath are made children of God (see Ephesians 2), and the Head “commissions them to perform Christ’s work. That’s where liturgists come from: They are regenerated. Christ is the firstborn of many little liturgists who perpetuate a Christic, kenotic, salutary, sacerdotal, prophetic, and royal work.”29

There is more to poetry than meter, and there is more to liturgy than rubrics.

As liturgists who are recreated and commissioned by Christ himself to perpetuate his work, we are called to bring all of creation together in a resounding praise of God. “All particular liturgies center round, are merged in, and draw their strength from, the collective liturgy of that great living organism the Church, which is the perfect man and the fulness of Christ. The whole life of the Church expresses and unfolds itself in its liturgy; all the relations of creatures with God here find their principle and their consummation.”30 The liturgy is, therefore, the ultimate common good in this life. A common good is not simply the conglomeration of individual, private goods. Nor is it an abstract good that people must out of duty strive for at the cost of their individual good. Rather, the common good is “a good which by nature is one in number but communicable to many. At the same time, the common good is a real and genuine good for the individual without being an individual good.”31

To truly be a good, it must aid in the achievement of man’s proper end, which St. Paul declares to be holiness—union with God: “For this is the will of God, your sanctification…for God has not called us for uncleanness, but in holiness” (1 Thessalonians 4:3, 7). The Church, furthermore, “like her divine Head, is forever present in the midst of her children. She aids and exhorts them to holiness, so that they may one day return to the Father in heaven clothed in that beauteous raiment of the supernatural.”32 This end is achieved primarily through the sacraments which “as considered by us now, is defined as being the sign of a holy thing so far as it makes men holy.”33 St. Thomas Aquinas identifies three reasons why the sacraments are necessary for salvation: “It follows, therefore, that through the institution of the sacraments man, consistent with his nature, is instructed through sensible things; he is humbled, through confessing that he is subject to corporeal things, seeing that he receives assistance through them: and he is even preserved from bodily hurt, by the healthy exercise of the sacraments.”34 The sacraments are a remedy for concupiscence and a source of sanctification designed specifically for mankind. The weaknesses of man, composed of body and soul, are appropriately and efficaciously addressed by the sensible and supernatural components of the sacraments. The Providence and design of God have made these remedies necessary, from our point of view, for salvation.35

–Image Source: AB/Wikimedia

Necessary Necessity

The external rites of the Church are not necessary for salvation in the same way the sacraments are necessary. Aquinas points out that “necessity of end…is twofold. First, a thing may be necessary so that without it the end cannot be attained; thus food is necessary for human life. And this is simple necessity of end. Second, a thing is said to be necessary, if, without it, the end cannot be attained so becomingly: thus, a horse is necessary for a journey. But this is not simple necessity of end.”36 He goes on to say that only Baptism (and in the case of mortal sin, penance) is necessary simply and absolutely for salvation. The other sacraments have a secondary necessity that is more fitting to achieve the ultimate end—sanctification. The same distinction can be applied further to the sacraments and the liturgy. Baptism (and penance) are absolutely necessary. The other sacraments sanctify men but, technically speaking, are not strictly necessary. Although, in practice, they are necessary. Man’s weakness is so great that each of the sacraments are necessary for the average man to overcome vice and become a saint. Likewise, the liturgical rites of the Church are not necessary in the same respect as any of the sacraments, but they definitively contribute to our sanctification. “For although the ceremonies themselves can claim no perfection or sanctity in their own right, they are, nevertheless, the outward acts of religion, designed to rouse the heart, like signals of a sort, to veneration of the sacred realities, and to raise the mind to meditation on the supernatural. To serve to foster piety, to kindle the flame of charity, to increase our faith and deepen our devotion. They provide instruction for simple folk, decoration for divine worship, continuity of religious practice. They make it possible to tell genuine Christians from their false or heretical counterparts.”37

The rites, ceremonies, prayers, etc. of the Church come together to form the liturgical year which contains all the feasts days, seasons, and commemorations that the Church makes in a year. The arrangement ensures that every mystery of faith, every doctrine, and every historical reality is presented to the faithful to guarantee an everlasting commemoration. The entirety of the liturgy generates “a drama the sublimest that has ever been offered to the admiration of man…. Each mystery has its time and place by means of the sublime succession of the respective anniversaries. A divine fact happened nineteen hundred years ago; its anniversary is kept in the liturgy, and its impression is thus reiterated every year in the minds of the faithful, with a freshness, as though God were then doing for the first time what He did so many ages past.”38 In our modern, Western culture, it can be difficult to understand how the liturgy could truly have such an overwhelming effect. But we must remember that the teleology of the liturgy is not meant to be achieved with one hour of exposure a week plus an occasional Holy Day of Obligation. Rather, “the ideal of Christian life is that each one be united to God in the closest and most intimate manner. For this reason, the worship that the Church renders to God…is directed and arranged in such a way that it embraces by means of the divine office, the hours of the day, the weeks and the whole cycle of the year, and reaches all aspects and phases of human life.”39

The liturgy is meant to sanctify every moment of life, not just one or two hours a week. To achieve this end the Church has developed since Apostolic times the Divine Office which consists of, primarily, the Psalter, short readings, responsories, hymns, antiphons, etc. Additionally, liturgical rites such as exposition, benediction, Stations of the Cross, etc. developed to extend the adoration of God beyond Mass: “The Divine Office and the Hours are but the splendid accompaniment, the preparation for or radiance from the Eucharist.”40 Such an extension ought to guide the spiritual life of Christians. The entire corpus of the liturgy is meant to act as a constant stimulus to raise the soul to God, to be recollected, to meditate on Divine truths. The realities that are commemorated in the liturgy are exceedingly different than those anniversaries and holidays we celebrate privately or civilly: “as the liturgy is all set out within the framework of the liturgical year, this framework contains not only an expression of the Mystery but also the reality of the Mystery.”41 In other words, the liturgy does not simply present before the eyes of the faithful a memorial of salvation history but provides a real participation in the events themselves.

Liturgy and Sanctity

Thus, it should now be clear that the liturgy, both in the sacraments and complementary rites of the Church, are the primary means by which the Church as a body, and individual members themselves, are able to grow in sanctity. The liturgy is the fundamental and primary prayer of Christians. All other prayers, private or communal, should come from and lead back to the liturgy of the Church—the most profound encounter with Christ in this life. Therefore, if the liturgy is fundamental and primary for our spiritual life, and if spiritual childhood is a necessary disposition to enter heaven, then it must needs be that the liturgy is the primary and fundamental means for growth in spiritual childhood. We will explore this more closely in next month’s installment.

For previous instalments of Steven Hill’s Spiritual Childhood from Liturgical Worship series, see:

Stephen Hill is an MTS student in Liturgical Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Prior to this program, he completed a BS in psychology and an MA in systematic theology. All of his research was inspired by several years of Benedictine formation, and the monastic tradition continues to influence his work. Hill strives to explore the intersection of contemporary psychological research and patristic psychological writings where both fields are most fully manifested: in the sacred liturgy.

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia. The Starry Night, by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Footnotes

- Prosper Gueranger, The Liturgical Year, “General Preface” (Powers Lake: Marian House, 1983), 1.

- Oliver Rousseau, The Progress of the Liturgy, trans. By the Benedictines of Westminster Priory (Westminster: The Newman Press, 1951), 3.

- Pius XII, Mediator Dei, 20.

- Gueranger, 8.

- Mediator Dei, 36.

- Louis Bouyer, Meaning of Monastic Life, 180.

- Mediator Dei, 37.

- Paul Delatte. The Rule of St. Benedict; a Commentary by the Right Rev. Dom Paul Delatte. Translated by Dom Justin McCann. (England: Burns, Oates & Washbourne, 1921), 131.

- Delatte, 131.

- Psalms 148-150 prayed together under one Gloria Patri. The monastic breviary retains this practice as it is mentioned explicitly in the Rule of St. Benedict. The practice was ended by St. Pius X’s reform explained in Divino Afflatu. Although there is usually a laudate Psalm at the end of Lauds in the current edition of the Roman Breviary, the practice of reciting all three each morning has ceased.

- Delatte, 131

- Delatte, 131.

- Delatte, 132.

- Delatte, 132.

- David Fagerberg, Theologia Prima: What is Liturgical Theology? (Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2004), 11.

- Lawrence Madden, “Liturgy,” The New Dictionary of Sacramental Worship, ed. Peter Fink, (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1990) 740.

- Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1976) 25.

- Fagerberg, 11.

- See 1 Corinthians 12

- Fagerberg, 7-8.

- Fagerberg, 7

- Fagerberg, 8.

- Fagerberg, 8.

- Fagerberg, 8.

- Fagerberg, 8.

- Fagerberg, 8-9.

- Fagerberg, 9.

- Fagerberg, 11.

- Fagerberg, 12.

- Delatte, 133.

- Steven Long, Teleological Grammar of the Moral Act, ___.

- Pius XII, Mediator Dei, 22.

- Summa Theologiae, III, q. 60, a. 2: “secundum quod nunc de sacramentis loquimur, quod est signum rei sacrae inquantum est sanctificans homines.”

- ST, III, q. 61, a. 1.

- God himself is not bound by the sacraments and may freely disperse grace as he sees fit. Yet we do not have the right to seek grace outside of the sacramental order that God has established.

- ST, III, q. 65, a. 4.

- Giovanni Cardinal Bona, de divina psalmodia, c. 19, par. 3, 1.

- Gueranger, 14.

- Mediator Dei, 138.

- DeLatte, 133.

- Louis Bouyer, Liturgical Piety (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1955), 189.