“And Jesus answered him, ‘Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born anew, he cannot see the kingdom of God.’ Nicodemus said to him, ‘How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter a second time into his mother’s womb and be born?’ Jesus answered, ‘Truly, truly I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God” (John 3:3-5).1

A consistent theme throughout the Gospel of John is an apparent disconnect between the teaching of Our Blessed Lord and the understanding of his disciples. We should not scoff at the early disciples of Christ, however, because, in many respects, we are no better. For instance, although any decently catechized Catholic can confidently describe baptism as a spiritual rebirth, many ask the same question as Nicodemus: how can a man become a child again once he is old?

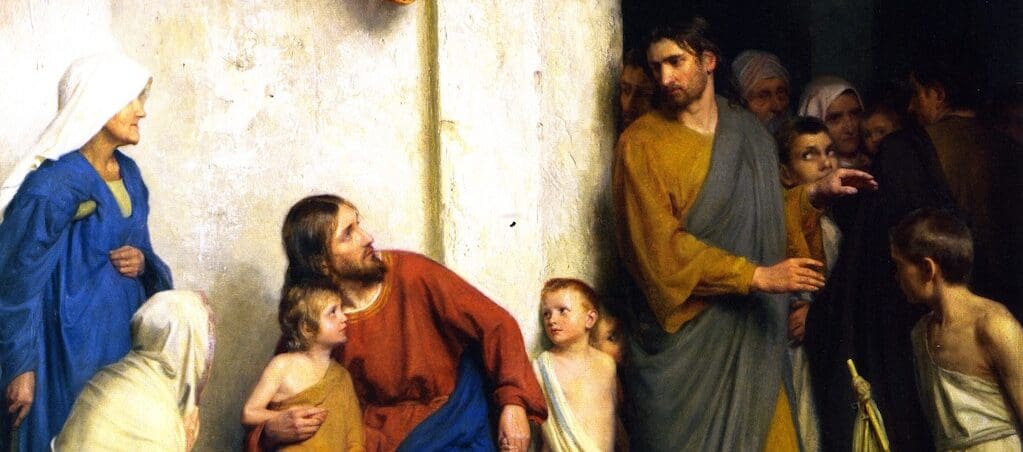

Spiritual childhood is so vital to the Christian life that this teaching comes from the mouth of Our Lord himself as related by all three synoptic Gospels (Matthew 18:3, 19:14; Mark 10:15; Luke 18:17). Indeed, since our Lord considers this disposition necessary in order to enter heaven, he continues to teach it through his Church. Perhaps most prominently, our Lord renewed this teaching by giving St. Thérèse of Lisieux a double portion of that true, childlike spirit. Despite only composing a short autobiography and some letters and poems, she has exercised more influence over the past century than many prolific authors.

There is no doubt that the “little way” of spiritual childhood proposed by St. Thérèse has had a wide-sweeping influence in the life of Christians. Her sway began small when “she taught the way of spiritual childhood by word and example to the novices of her monastery.”2 After her death, her doctrine was “set forth clearly in all her writings which have gone to the ends of the world, and which assuredly no one has read without being charmed thereby, or without reading them again and again with great pleasure and much profit.”3 Over the past century, the Magisterium has consistently promoted a devotion to her and her doctrine. Pius XI, who beatified and canonized her, declared at her canonization, “We nurse the hope today of seeing springing up in the souls of the faithful of Christ a burning desire of leading a life of spiritual childhood [original emphasis].”4 St. John Paul II, who shared the hopes of Pius XI, proclaimed St. Thérèse a Doctor of the Church in 1997.5 By doing so, he conferred upon her “an outstanding recognition which raises her in the esteem of the entire Christian community beyond any academic title.” A Doctor of the Church is one whose doctrine “can be a reference point, not only because it conforms to revealed truth, but also because it sheds new light on the mysteries of faith, a deeper understanding of Christ’s mystery.”6

St. Thérèse was instrumental in explicating the doctrine of spiritual childhood. She may be fittingly compared to another Doctor of the Church: St. Francis de Sales. Father Louis Bouyer of the Oratory, in his book The Meaning of Monastic Life, wrote that the glory of St. Francis de Sales was that “he has discouraged Christians living in the world from imitating the externals of monasticism, while helping them to adopt and adapt its vital principles.”7 The same praise should be given to St. Thérèse concerning spiritual childhood. She reiterated this ancient and venerable doctrine in a manner accessible to the masses. Therefore, her autobiography and letters have justly merited for her the title of Doctor of the Church.

Many souls might easily read The Story of a Soul, become convinced of the absolute necessity of spiritual childhood and the way of love, but remain mystified at the possibility of attaining it. Or, to put it in the words of G.K. Chesterton, “we have sinned and grown old” and are unable to become children again.8 St. Thérèse, it is said, never committed a mortal sin. She never lost the spirit of childhood which she assiduously taught. Initially, therefore, it seems more difficult for the average Catholic, weighed down by a history of sin, to regain the spirit of childhood compared to someone who never lost it. Yet, God never demands the impossible. He has certainly given his children the tools necessary to attain their end. In this series, I will demonstrate that the fundamental and principal source of initiation into, and development of, spiritual childhood lies in the liturgy of the Church.

There will be five subsequent parts developing this argument. The first part demonstrates that the customs of monastic life are among the most universally accessible practices in the Church. Other spiritual traditions (e.g., Carmelite, Jesuit, etc.) contain practices that are more akin to specializations within the taxonomy of the spiritual life. Monasticism is the spiritual equivalent of a general practitioner and other forms are like cardiologists, neurologists, pediatricians, etc. Principally, we will review the writings of Dom Paul Delatte and Father Louis Bouyer here. These authors show us that if monasticism has handed on many accessible spiritual practices, and if spiritual childhood is necessary for sanctity, then the monastic tradition is a worthy place to search for such tools in our formation. Finally, after establishing the primacy of monasticism in this search of ours, we should next examine their primary form of prayer: the liturgy.

The second part explores the liturgy as the primary form of prayer for Catholics. Sources for Part II include magisterial texts, monastic authors (e.g., Gueranger, Delatte, Marmion, Bruyere), as well as Bouyer, and the liturgy scholar David Fagerberg. The objective therein is to demonstrate that if spiritual childhood is as necessary to the spiritual life as has been asserted, and if the liturgy is truly the most fundamental form of prayer for Catholics (indeed, the only required form of prayer), then the liturgy must in some way be responsible for the formation of spiritual childhood. How the liturgy forms the faithful as children will not be addressed in this second part. Rather, it is focused on demonstrating that the liturgy is the appropriate place to seek a pedagogical formation in spiritual childhood.

The climax of the series occurs in Part III. Within this part of the series, I show the profound reality that it is within the liturgy of the Church that we are made children of God. This occurs metaphysically and psychologically. We continue to grow and develop in spiritual childhood on a supernatural plane through the liturgy and in particular the Sacraments. Additionally, the liturgy exerts a psychological influence that deepens the spirit of childhood within us. Part III is further divided into two subsections: the first builds upon magisterial texts, the writings of Marmion, Gueranger, and Bouyer to establish our entrance into and growth in spiritual childhood through the sacraments and liturgy. The second subsection, on the other hand, focuses on a more practical dimension of spiritual childhood, viz., which dispositions are requisite for true spiritual childhood. Primarily, this includes simplicity, docility, and participation in eternity. In addition to previously cited authors, Part III also references G.K. Chesterton as an incisive and influential Catholic writer who has clearly taken the notion of spiritual childhood to heart.

After demonstrating how the liturgy forms the Christian soul in spiritual childhood, both metaphysically and psychologically, the fourth part of this series shifts back to monastic spirituality. Since the monastic life was previously shown to be the most concentrated form of the Christian life, it is a fruitful endeavor to demonstrate how the monastic life incorporates the principles of spiritual childhood into practice extended throughout the day, the week, the year, and the entirety of life. In other words, how do monks and nuns live out the formation they receive in the liturgy?

The series concludes with a practical section. In the spirit of St. Francis de Sales and Louis Bouyer, there is no reason to attempt to artificially mimic the external practices of monastic life among the laity. The laity are not Religious-Lite nor are we simply non-actualized Religious. That being said, we can and absolutely should distill the essence of their disciplines and find the most fruitful application of those principles in our own lives. Thus, as a fitting conclusion to this series, we examine many practical tips and suggestions for truly living out the formation in spiritual childhood which the liturgy so richly provides us.

Editor’s note: Look for the next installment of “Spiritual Childhood” in next month’s AB Insight.

Stephen Hill is an MTS student in Liturgical Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Prior to this program, he completed a BS in psychology and an MA in systematic theology. All of his research was inspired by several years of Benedictine formation, and the monastic tradition continues to influence his work. Hill strives to explore the intersection of contemporary psychological research and patristic psychological writings where both fields are most fully manifested: in the sacred liturgy.

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia Commons: Carl Bloch: Let the Little Children Come Unto Me

Footnotes

- Biblical quotations are from the RSVCE unless otherwise noted.

- Homily of Canonization given by Pope Pius XI. See, Rev. Thomas N. Taylor, Saint Thérèse of Lisieux: The Little Flower of Jesus, (New York: P.J. Kennedy & Sons, 1930), 271.

- Taylor, 271.

- Taylor, 272.

- John Paul II, Proclamation of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face as a Doctor of the Church, Homily, Vatican Website, October 19, 1997, https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/homilies/1997/documents/hf_jp-ii_hom_19101997.html.

- John Paul II, sec. 3.

- Louis Bouyer, The Meaning of Monastic Life, trans. Kathleen Pond (New York: P.J. Kennedy & Sons, 1950), ix.

- G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc., 2004), 52.