For what now lies beneath the aforementioned species is not what was there before, but something completely different; and not just in the estimation of Church belief but in reality, since once the substance or nature of the bread and wine has been changed into the body and blood of Christ, nothing remains of the bread and the wine except for the species—beneath which Christ is present whole and entire in His physical “reality,” corporeally present, although not in the manner in which bodies are in a place.1

St. Thomas More Parish, located in an impoverished neighborhood of Scranton, PA, is the first parish property purchased by the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter. Established in 2009 by the late Pope Benedict XVI’s Anglicanorum coetibus, to receive those of the Anglican tradition into full communion with the Church, the US-based personal ordinariate is one of three ordinariates, along with Our Lady of Walsingham of the United Kingdom and Our Lady of the Southern Cross of Australia. Two years ago, I began attending Divine Worship in choro at the hospitable invitation of the pastor, Father Eric Bergman, and with the encouragement of Dr. Carmina Chapp. Training soon began in the celebration of the Said Mass, Sung Mass, and Solemn Mass in the roles of deacon and priest. My love of the rites coupled with the vibrancy of the parish’s life—a crisis pregnancy center, daily communal Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, a K-12 academy, intentional neighborhood outreach, and parishioners’ farms—drew me to assist sacramentally on a regular basis.

Divine Worship according to the Ordinariate is a ritual beautiful in its orations and structure, drawing from the rich heritages of both Roman and Anglican liturgies. Here, I wish to highlight the Prayer of Peace because it continues to make a powerful impact upon my priesthood and is quite effective in drawing the mind to the reality of the Real Presence of Christ on the altar, a perennially important topic and especially so in this time of the Eucharistic revival.

Word and Gesture

The rubric for “The Peace” according to the Divine Worship Missal states, “Then bowing in the middle of the altar, with hands joined upon it, the Priest says: ‘Lord Jesus Christ who saidst to thine Apostles, Peace I leave with you; my peace I give unto you: regard not our sins, but the faith of thy Church; and grant to her peace and unity according to thy will; who livest and reignest with the Father and the Holy Spirit, ever one God, world without end. Amen.’”2

The rubric to bow and the prayer itself are known by those familiar with the 1962 Missale Romanum (MR62) issued by Pope St. John XXIII since both are present. MR62 states, “Deinde, iunctis manibus super altare, inclinatus dicit secrete sequentes orationes: ‘Domine Iesu Christe, qui dixisti Apostolis tuis: Pacem….’”3 This prayer dates back to the beginning of the 11th century in the Roman tradition.4 Interestingly, this prayer is found in the 2001 Missale Romanum, but the directive to bow—inclinatus—is not. Why then does the Ordinariate’s Divine Worship Missal include the rubric to pray the Prayer of Peace with a bow?

Here it is helpful to turn to the rich tradition of English Uses, namely the Sarum, Bangor, York, Lincoln, and the Hereford Uses—all frequented by Christians until the Act of Uniformity of 1549. Dating to 1070, the Sarum Use originated at Salisbury Cathedral and enjoys the greatest of esteem. Dated also from the 11th century, the Hereford Use was prayed primarily in the South of Wales.5 The prayer, “Domine Iesu Christe, qui dixisti Apostolis tuis…” is present in the Hereford Use, but the rubric to bow is not.6 The Sarum Use includes a prayer similar to the “Domine Iesu Christe, qui dixisti Apostolis tuis…,” but does provide the rubric, “Hic inclinet se sacerdos ad hostiam dicens.” 7

As found in the Roman and Sarum traditions, the Ordinariate rite directs the celebrant to pray the Prayer of Peace while bowing to the altar upon which rests the consecrated elements. Importantly, both the words prayed and the gesture performed affirm that Christ Jesus is now present upon the altar. The words and gesture assist the celebrant and the congregation to recognize that at this point of the Mass we address not the Father, but the Son present to us in the Sacrament. This is an important shift in the Mass: to whom we address changes.

I am nothing short of delighted to have renewed in my mind this shift in address, thanks to my regular participation in the Ordinariate liturgy. And with humility, I wonder how many Catholics are aware that prayers have changed from addressing the Father to addressing the Son who is present on the altar. Now, when celebrating the Roman Rite, at the Prayer of Peace, I make a very slight and subtle bow to the host so as to acknowledge by gesture that Christ is truly present while at the same time respecting the integrity of the Roman Rite.

The words are plainly addressed to the Son—“Domine Jesu Christi, qui dixisti Apostolis tui…”—but the addition of gesture—a bow directed to the consecrated elements—reinforces this change of address. Here, then, is a prime example of word and gesture working in tandem to communicate a reality. We read, “More than simply conveying information, a mystagogical catechesis should be capable of making the faithful more sensitive to the language of signs and gestures which, together with the word, make up the rite.”8 As pointed out by Helen Hull Hitchcock, the sacred mysteries cannot be fully understood by words alone—a “super-rational approach.” Gestures communicate in bodily form what the words convey in textual form. Both contribute to our praying well.

Bowing toward the consecrated elements during the Ordinariate rite has deepened my awareness of and attentiveness toward the Real Presence of Christ on the altar, because such a reality is affirmed verbally and bodily. This is also a sociological phenomenon.

My growing familiarity with and experience of praying according to the Divine Worship liturgy coincided with hearing a talk given by Audra Dugandzic, Ph.D., who earned her doctorate in sociology from the University of Notre Dame this Easter Monday. Dugandzic gave a luminous presentation at the Society for Catholic Liturgy’s conference in September 2023 on this very point of the importance of gestures. Dugandzic highlighted Peter Berger’s The Sacred Canopy and his discussion on “plausibility structures.” These structures are reliable habits that make us presume that something is real. Dugandzic pointed to the practice of genuflecting to the tabernacle—interestingly, this is how Hitchcock begins her article linked above. The habitual gesture of genuflecting to Christ present in the tabernacle is a structure that gives plausibility to the reality that Christ is indeed present in the tabernacle. Conversely, to not genuflect (or some similar gesture such as bowing by those unable to genuflect) decays the plausibility of the Real Presence.

Plausible Reality

This insight can be applied to our topic at hand. The words of The Peace are addressed to Christ Jesus and the gesture of bowing to the consecrated elements provides a “plausibility structure” that reinforces our belief in the Real Presence.

Much of the Mass is prayed to the Father, through the Son, and in the Holy Spirit. But, as Chris Carstens explains, “at the sign of peace, when the paschal Christ is on our altar and in our midst, we begin to speak directly to him: ‘Lord, Jesus Christ, who said’; we sing to the ‘Lamb of God’; the priest prays directly to Christ in his private prayers after the Lamb of God; he shows us the Lamb of God; I respond to him, ‘Lord, I am not worthy’; etc. In short: with the sign of peace, a remarkable shift occurs.”9 Indeed. Participating more fully in the Mass means possessing an awareness of this change of address.

I am particularly aware that the Sarum Use directs the celebrant to bow towards the host, “Hic inclinet se sacerdos ad hostiam dicens….” This is precisely the mind of the pastor at St. Thomas More Parish who explained it to me in exactly this way. Fully aware that Christ is present on the altar, the celebrant is bowing and is addressing directly Christ present in the consecrated elements. This theology and practice is supported by the quote from Pope St. Paul VI which began this essay. “For what now lies beneath the aforementioned species is not what was there before, but something completely different; and not just in the estimation of Church belief but in reality….”10 As mentioned before, the Sarum Use has similar words as The Peace and includes a beautiful line. Inclining toward the host, the celebrant prays, “Te adoro, te glorifico, te tota cordis intentione laudo et precor….”11 I adore you, I glorify you, I praise you with all the intentions of my heart and I pray….”

A change of address occurs. Gestures, whether genuflecting, bowing, striking the breast, etc., affirm the spoken word. And consequently, this marriage of word and gesture “make up the rite.”12 Furthermore, the marriage of word and gesture is an important element of our renewed understanding of not just the plausible, but the very Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist.

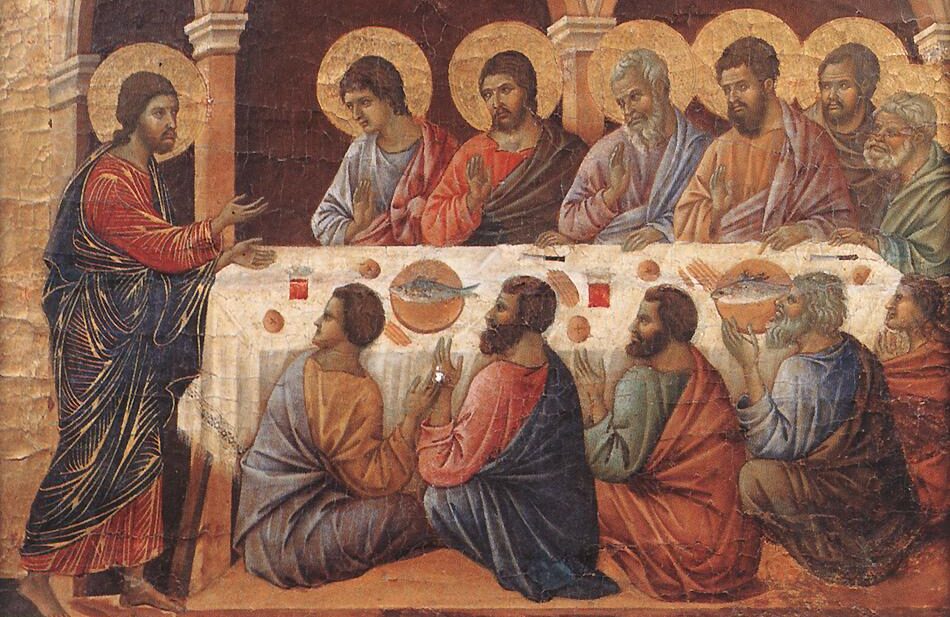

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia. Appearance While the Apostles are at Table (between 1308 and 1311), by Duccio

Footnotes

- Pope St. Paul VI, Mysterium Fidei, September 3, 1965, no. 46.

- Divine Worship: The Missal, The Catholic Truth Society: London, 2015, pg. 651.

- Missale Romanum edition typica 1962, Edizione anastatica e Introduzione a cura di Manlio Sodi e Alessandro Toniolo, Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Città del Vaticano, 2007, pg. 402. Emphasis mine.

- See The Traditional Mass by Michael Fiedrowicz, pg. 110.

- See Use of Hereford: The Sources of a Medieval Diocesan Rite by William Smith, 2015.

- Maskell, William, The Ancient Liturgy of the Church of England, According to the Uses of Sarum, Bangor, York and Herford, and the Modern Roman Liturgy (3rd ed. Oxford 1882), pg. 53.

- Maskell, William, The Ancient Liturgy of the Church of England, According to the Uses of Sarum, Bangor, York and Herford, and the Modern Roman Liturgy (3rd ed. Oxford 1882), pg. 54.

- Benedict XVI, Sacramentum Caritatis, no. 64.

- Personal correspondence.

- Pope St. Paul VI, Mysterium Fidei, September 3, 1965, no. 46.

- Maskell, William, The Ancient Liturgy of the Church of England, According to the Uses of Sarum, Bangor, York and Herford, and the Modern Roman Liturgy (3rd ed. Oxford 1882), pg. 54.

- Benedict XVI, Sacramentum Caritatis, no. 64.