We cannot build up the idea of the apostolate of the laity without the foundation of the liturgy.” 1

I came to know of Dorothy Day during my senior year at the University of Notre Dame. I had just returned from a study abroad program in Rome, where I had the blessing of experiencing in audience the greatness that was St. John Paul II. I saw the bones of St. Peter. The reality of the person of Jesus, his Incarnation and Resurrection, struck me to the core of my consciousness. I fell in love with my faith and with Holy Mother Church.

At moments of conversion like this, we look to the saints, first for affirmation of our conversion, and then for examples of what life looks like for the converted. Upon my return from Rome, I was edified in the former, but lacking the latter. The saints with which I was familiar were mostly religious men and women who lived in historical circumstances far different from my own. Who were the examples of living the Christian life in modern day America? Enter Dorothy Day and her 1952 autobiography, The Long Loneliness, assigned to me in a Catholic Social Teaching class.

Born November 8, 1897, in New York City, Dorothy Day founded the Catholic Worker Movement with Peter Maurin in May during the Great Depression in 1933. Their vision for this movement, which continues to this day, was to found self-sustaining communities, modeled on the justice and charity embodied by Jesus Christ, which would serve the poor and marginalized in society. A Catholic convert well-known for her journalism and political activism, Day lived Catholic social teaching to its fullest, and advocated for all Catholics, religious and laity, to do so. Here was an example for me of a lay woman living out her faith in 20th century America. What hope!

Foundation of a Movement

Day was ahead of her time as a lay person leading a lay ministry committed to living out the Corporal Works of Mercy. Surely, had she been born even 50 years earlier, she would have been encouraged by the Church to establish a religious order for such purposes. As a lay movement of the Catholic Church, the Catholic Worker was neither a religious order nor a secular organization doing social work (what today we might call an NGO). It is a lay movement doing the work of Jesus Christ. Christ comes first. Christ always comes first. For this reason, the liturgy of the Church is essential to the Catholic Worker staying true to its roots. Both Day and Maurin were thoroughly saturated with the liturgical life of the Church.

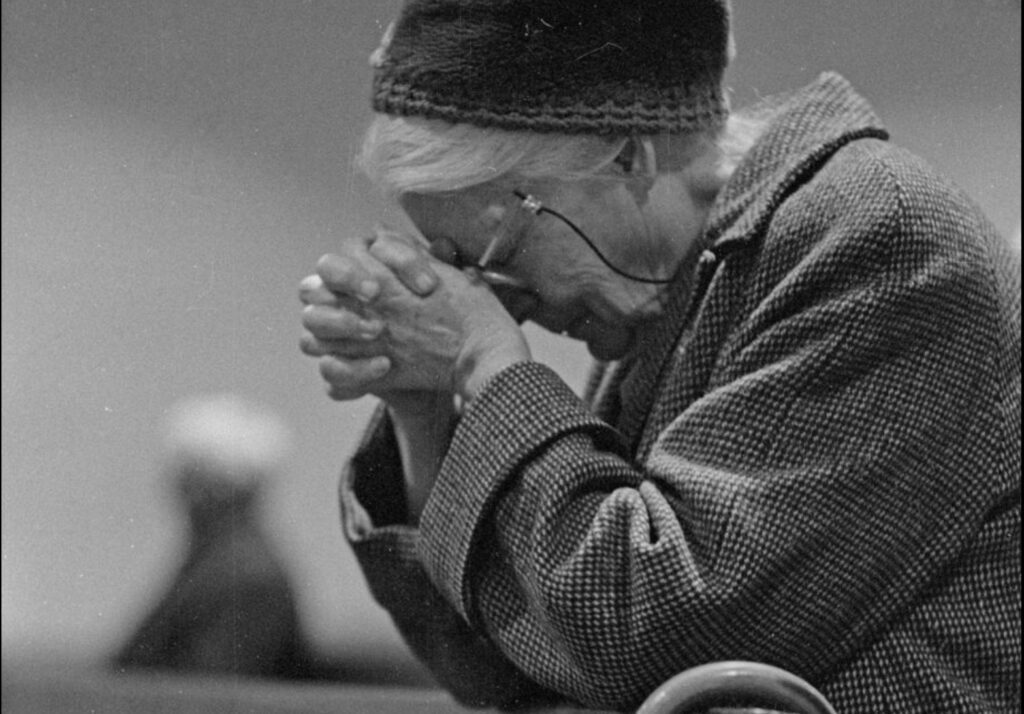

Day was a daily communicant. She found her strength in the Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. The Liturgical Movement of the 20th century interested her greatly, as it attempted to bring about a greater awareness to the laity of what is happening, and especially what they are actively doing—offering their lives to the Father through Christ, in the celebration of the Mass. She was familiar with the writings, liturgical and otherwise, of Father Romano Guardini and Benedictine Father Virgil Michel, and knew from her own experience that a conscious participation in the Mass was vital to her ability to do the work she was doing in the world. As she wrote in her column in the movement’s newspaper, The Catholic Worker:

“The basis of the liturgical movement is prayer, the liturgical prayer of the church. It is a revolt against private, individual prayer. St. Paul said, ‘We know not what we should pray for as we ought, but the Spirit Himself asketh for us with unspeakable groanings.’ When we pray thus we pray with Christ, not to Christ. When we recite prime and compline we are using the inspired prayer of the church. When we pray with Christ (not to Him) we realize Christ as our Brother. We think of all men as our brothers then, as members of the Mystical Body of Christ. ‘We are all members, one of another,’ and, remembering this, we can never be indifferent to the social miseries and evils of the day. The dogma of the Mystical Body has tremendous social implications.”2

Daily Mass was not simply a pro-forma exercise for Day, a mere habit she had formed. She expected it to have a real effect on the way she interacted with those our Lord put in her path each day. “If daily Mass and Communion do not make people kinder, milder, gentler, it must be very saddening to Our Lord.”3 Dorothy often pondered her own failure to live the faith and was keenly aware of her need for grace, particularly sacramental grace. Her outreach to the poor was her way of living out the sacrifice of her own life to God, which she offered every day in the liturgy. Her life was an example of a healthy integration of contemplation and active ministry.

Day was also ahead of her time in her praying of the breviary. Her participation in liturgy was extended throughout the day with her reading and praying the psalms. Long before St. John Paul II encouraged the laity to pray the Liturgy of the Hours, Dorothy Day was already drawn to it. Eventually, in 1955, at the age of 58, she made her final oblation as an Oblate of St. Benedict through St. Procopius Abbey in Lisle, IL, taking the name Benedicta. One of her more famous quotes refers to this practice: “My strength returns to me with my cup of coffee and the reading of the psalms.”

Inspired by Day to become an Oblate of St. Benedict, I can appreciate her Benedictine spirituality and how it encapsulates her entire ministry. Three aspects of this spirituality are especially relevant: simplicity of life, hospitality, and the care of creation. To put these in perspective, we must understand the Benedictine concept of “Ora et Labora.”

“Idleness…enemy of the soul.” 4

A Benedictine spirituality is a beautiful integration of prayer and work, a lesson all laity can learn, especially in these stress-filled, workaholic times. Dorothy Day’s robust liturgical life exemplified this integration. St. Paul tells us to pray without ceasing. Our prayer must flow into our work, and back into our prayer.

Work is not simply the arbitrary thing we do to make a living and pay the bills. Indeed, we are given a vocation, our own personal means by which each of us builds the Kingdom of God. We trust that in doing God’s will, he will provide for our needs. When we integrate our prayer and work, we find our vocation and can flourish.

When I first read The Long Loneliness, I was so inspired by Day that I imagined myself living in a House of Hospitality, wearing jeans and a gray sweatshirt everyday for the rest of my life. But God had other plans for me. My prayer life led me to a doctorate in theology and a position teaching seminarians and lay students. My work, my career, was in response to my prayer, and I brought all that I encountered in my work to my prayer. Prayer not only reveals God’s will to us, it also gives us the courage to step out and do it.

For the Benedictine, work is a creative outlet. We are to glorify God with our lives, and so our work manifests the particular gifts that God has given to us. Our motivation is always Christ. We do our work to the best of our ability because we do it for him. In those we encounter during our workday, we encounter him. We do all things for Christ. “Whatever you did for the least of these, you did for me” (Matthew 25:40).

We can only appreciate Day’s practice of a Benedictine spirituality—her simplicity of life, her radical hospitality, and her care of God’s creation—in light of this attitude toward work and prayer. Especially as a lay woman, and not a religious, Day’s commitment to integrating prayer and work seemed odd in her day. Yet, it is exactly what Vatican II called for in Lumen Gentium. The universal call to holiness is for all of us. Once again, Day was ahead of her time.

Day’s life of simplicity was manifested in her voluntary poverty and in her solidarity with the poor. She lived with and like the poor, even after the Great Depression was over. Her ability to maintain this lifestyle was related to her practice of radical hospitality. Following the example of her mentor, Peter Maurin, if she had something that someone else needed, she gave it to them. If she was able to help, she did. In helping others, she found that all her needs were met, too. Her vocation was sustained by God himself, who provided the means for her to continue.

Maurin’s influence on Day is also seen in her love and vision for the Catholic Worker farms. While Maurin looked to the farms as agronomic universities where people would learn the value of going back to the land and gaining knowledge and appreciation of how God created humans to be sustained by it, Day saw them also as places of respite for the city worker, somewhere to experience God in the quiet, peaceful atmosphere of nature. Manual labor on the farm, the proper care for creation, integrated with opportunities for prayer, complete the Benedictine vision.

Day’s commitment to the liturgical practice of the Church empowered her to boldly spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ in both word and action. Catholic doctrine and social teaching permeated everything she did. She explains beautifully her understanding of ecclesiology and the role of liturgy in forming the Church in another article in The Catholic Worker:

“The Mystical Body of Christ is a union—a unit—and action within the Body is common action. In the Liturgy we have the means to teach Catholics, thrown apart by Individualism into snobbery, apathy, prejudice, blind unreason, that they ARE members of one body and that ‘an injury to one is an injury to all.’”5

Her prayer life, and particularly her liturgical life, brought her into an intimate relationship with Jesus, which enabled her to see her neighbor, any neighbor, as a brother or sister in Christ. She had a bond with people only seen in the saints.

In Hoc Signo Vinces

Though she famously said that she did not want to be called a saint, she is exactly the example of holiness needed for Catholics today. Day did not want to be dismissed as a “saint” because it would put her in some higher category out of reach of the average person. The point of her life, however, was to show that every human being not only is called to be holy, but actually can be holy, by the grace of God—grace obtained in the participation of the sacraments. She was convinced that Catholicism radically lived is the only answer to our human misery. She continues in the same article with a rallying cry: “Our faith is stronger than death, our philosophy is firmer than flesh, and the spread of the Kingdom of God upon the earth is more sublime and more compelling. We Catholics must pray, act and sacrifice together for Christ the King, for the spread of His Kingdom and the salvation of the world. We Catholics, together, can conquer the world.”6

Yes, we Catholics, together, can conquer the world! We see so much infighting in the Church today, and it hinders our ability to evangelize. Day’s approach to evangelization is simple—to know Christ is to love Christ, to love Christ is to love your neighbor. Christ comes first. Christ always comes first.

Footnotes

- Dorothy Day, The Catholic Worker, January 1936, 5.

- Dorothy Day, The Catholic Worker, January 1936, 5.

- Dorothy Day, The Duty of Delight: The Diaries of Dorothy Day, June 16, 1951., p. 173.

- Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter 48.

- Dorothy Day, The Catholic Worker, December 1935, 4.

- Dorothy Day, The Catholic Worker, December 1935, 4.