Pope St. Pius X issued the motu proprio Tra le Sollecitudini on the feast of St. Cecilia, November 22, 1903, and the Council Fathers of Vatican II voted on the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, on the same date 60 years later. This year, November 22nd gives us the opportunity to revisit Tra le Sollecitudini, 60 years after the Council Fathers voted on Sacrosanctum Concilium.

Pius X wrote Tra le Sollecitudini,1 (“Among the concerns”) as a motu proprio, i.e., something done on his own initiative and not in response to something else; in doing so, Pius X signaled to the Church that the sacred liturgy and sacred music were of special interest to him. In fact, the liturgy was something that he was already concerned about when he was the Patriarch of Venice and before he was elected pastor of the Universal Church.

From our perspective of 120 years, looking back on Tra le Sollecitudini, what can we glean from it that is apropos to our own time? First of all, this document is not essentially focused on liturgical music, although it is often described as such. Rather, Pius X sees liturgical music as a contributing element to attaining to what he calls “the true Christian spirit,”2 and he sees the goal of the liturgy itself as being “the glory of God and the sanctification and edification of the faithful.”3 Liturgical music contributes to both of these, and for that reason he considers it to be important. It is essential to keep things in perspective, for Tra le Sollecitudini, the sacred liturgy, and therefore liturgical music serve the purpose of attaining the true Christian spirit and are vital to the glory of God and the sanctification of the faithful in the sacramental life of the Church.

The True Christian Spirit

With this background, one must also take into account the fact that Pius X is dealing with a Latin liturgy whose liturgical books derive from the liturgical reform of the Council of Trent. So given that fact, what do we find in Tra le Sollecitudini that remains as a constant for both his time and ours?

Both Tra le Sollecitudini (originally written in Italian) and Sacrosanctum Concilium are concerned with the faithful acquiring the true Christian spirit. In the introduction to Tra le Sollecitudini, Pius X states that he has a most ardent desire to see the true Christian spirit flourish in every respect and to be preserved by all the faithful. Sacrosanctum Concilium 14 is even more direct as to how the faithful derive the true Christian spirit. That document states that the sacred liturgy is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive this true Christian spirit.

Further on in the introduction to Tra le Sollecitudini, we find the expression “partipazione attiva” (active participation), used for what seems to be the first time in papal teaching in reference to the participation of the faithful in the sacred liturgy. In Tra le Sollecitudini, Pius X states that by “partecipazione attiva” in the public and solemn liturgy of the Church, the Christian faithful drink in the true Christian spirit from its primary and indispensable source. Unfortunately, however, in the text of Tra le Sollecitudini, Pius X never describes exactly what he means by “partecipazione attiva.” Nonetheless, the expression was fostered by the liturgical pioneers of the first half of the 20th century and became an essential element of the liturgical reforms of Vatican II.

In the introduction to Tra le Sollecitudini, we find the expression “partipazione attiva” (active participation), used for what seems to be the first time in papal teaching.

That lack of clarity becomes even more obvious in the Latin version of Tra le Sollecitudini that was published with the Italian original in the same volume of the Acta Sanctae Sedis. It is interesting that the Latin text of Tra le Sollecitudini does not use the Italian expression “partecipazione attiva” or the Latin phrase “actuosa participatio” which appears in Sacrosanctum Concilium. It speaks only of the faithful’s “participatio divinorum mysteriorum” (participation in the divine mysteries).4 The Italian original is the official text, but the Latin translation is listed as a Versio fidelis, a faithful translation of the Italian original. The fact that the Latin version does not speak of “participatio actuosa” seems to indicate that the Latin translator did not think that the participation of the faithful needed to be more active than their participation in the divine mysteries already was at that time for those who were regularly present at Mass. But the Italian expression “participazione attiva” also begs the question: since the liturgy in 1903 was in Latin and since one’s actions in it were very much determined by the rubrics of the Missale Romanum of those days, what sort of more active participation could the assembly of the faithful have engaged in?

It is important to understand the “partecipazione attiva” of Pius X in the context in which he was writing, i.e., when the modern liturgical movement was still in its infancy and not unconsciously thinking of it in the context of the more participatory liturgy that has developed since Vatican II. In 1903, it was still common to speak of attending Mass or hearing Mass, e.g., did you attend Mass today or did you hear Mass today? Mass was going on and people attended it even if they were not involved in it, and to the extent that the Mass was a High Mass or Solemn High Mass, they would have heard Mass or at least parts of it from the choir. Also, if they went to a Low Mass, they were at Mass, even if they would not have heard anything (i.e., they attended Mass even if they might have been praying their rosary the whole time). But attendance at Mass was certainly sufficient to fulfill one’s Sunday obligation. Perhaps Pius X, in Tra le Sollecitudini, was referring to the “Missal Movement,” i.e., people using hand missals in order to follow along in the vernacular what the priest was saying in Latin at the altar. Although the Missal Movement was still in its early stages, there already existed Gérard van Caloen’s Missel des Fidèles which was first published in French in 1882 and Anselm Schott’s hand missal that was first published in German in 1884.5

Active participation is not a good translation of “actuosa partipatio,” which we find in Sacrosanctum Concilium 14.

Although a more profound consideration of this issue would go beyond the scope of the present article, it is this author’s contention that active participation is not a good translation of “actuosa partipatio,” which we find in Sacrosanctum Concilium 146 and many subsequent documents on the sacred liturgy. I would maintain that engaged participation might be a more appropriate translation and one that is certainly justifiable when considering the Latin expression “participatio actuosa.” The Merriam-Webster online dictionary describes the word active as being characterized “by action rather than contemplation,” something that “produces or involves action or movement,” and which describes “one who is marked by vigorous activity.”7 That understanding of active participation hardly takes into account the reflective listening to the readings, gospels, and homilies, as well as the self-offering, that is expected of those participating in the sacred liturgy. It also neglects the contemplative dimension of the sacred liturgy that is so essential to it, or as Pope Pius XII writes in Mediator Dei 23-24: “The worship rendered by the Church to God must be, in its entirety, interior as well as exterior…. [B]ut the chief element of divine worship must be interior.”8

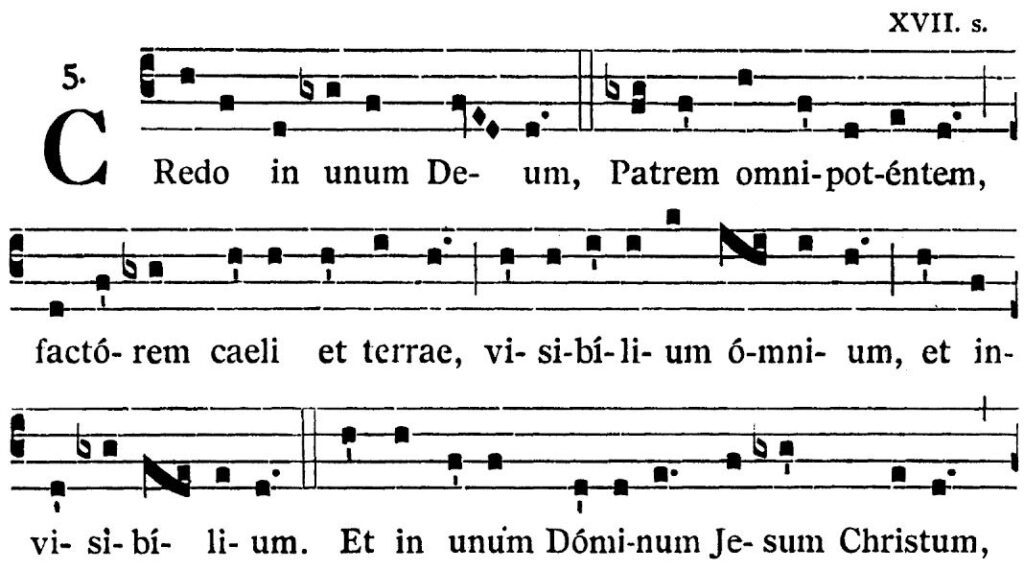

Gregorian Chant

When considering liturgical music in particular, Pope Pius X, called for it to be sacred, true art, universal, and excluding all profanity, elements that he says are found in the highest degree in Gregorian chant, which he calls the chant proper to the Roman Church. This expression regarding Gregorian chant as being “the chant proper to the Roman Church” has been used as well in various other documents including: Sacrosanctum Concilium 116, Musicam Sacram 50a, Sacramentum Caritatis 42, and the General Instruction of the Roman Missal 41.9 Pius X wanted Gregorian chant to be restored to public worship. At the same time, he wrote that it is permitted for every nation to admit into its ecclesiastical compositions special forms that may constitute its native music.

It is worth asking ourselves if the music used in the sacred liturgy is such that it truly raises the heart and mind to God in prayer.

Although we live in a much different liturgical world than did Pius X, it is worth asking ourselves if the music used in the sacred liturgy is such that it truly raises the heart and mind to God in prayer as one celebrates Christ in his mysteries. Is it, in other words, what Pius X calls sacred and true art? As one archbishop and musicologist wrote in 2009 regarding the music used in the Catholic liturgy: “I am afraid that most of the music composed for the liturgy over the last decades, unlike the music composed in previous centuries going back as far as the Gregorian chant, will be consigned to oblivion.”10 For example, we have largely forgotten that there is traditional Catholic funeral music and, therefore, that even the English translations of the entrance antiphon Requiem aeternam and the communion antiphon Lux aeterna hardly find any place in Catholic funerals in our day.

The text of Pius X also forms an important part of the collection of writings on the liturgy that contributed to the formation of Sacrosanctum Concilium.

A challenge that we have today, one that was not so much a challenge for Pius X, is the issue of ritual music—that is, music that is repeated, music that is used again and again, music that is used in certain settings and which one can count on being used, e.g., at Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, at Benediction, at the various celebrations of the Liturgy of the Hours. While Tra le Sollecitudini certainly allows for and encourages new compositions, the liturgy during his time also had ritual music (e.g., the 18 Mass ordinaries, the Asperges me, the Veni, Creator Spiritus, and the Te Deum—or Holy God, We Praise Thy Name if one prefers the English vernacular). Ritual music is not just music that is used in liturgical rituals. Ritual music is music that is used again and again in those characteristic liturgical settings, so much so that people have come to count on it being there. They know it, and in this sense, they “own” it. It belongs to them, just as does the rest of the liturgy. I recall that when Jesuit Father Robert Taft was asked a number of years ago at a meeting of the Society for Catholic Liturgy, what can the Western Church learn from the East, he responded that Latin Catholics need to get over their “allergy to repetition,” and he emphasized that repetition is at the very heart of ritual.

Blueprint for True Reform

While our world, including our liturgical world, is quite different from that of Pius X, there is still much that we could ponder from Tra le Sollecitudini, a writing that in a very real sense authorized the liturgical movement to move ahead in the decades before Vatican II. The text of Pius X also forms an important part of the collection of writings on the liturgy that contributed to the formation of Sacrosanctum Concilium. The historical-critical method of interpreting sacred scripture teaches us that one must consider the historical, literary, social, and theological contexts that contribute to the composition of a scriptural text. The same is true of a conciliar constitution such as Sacrosanctum Concilium. To truly understand it, one must study the texts that contributed to the formation of the document. It is radically insufficient to study only the texts that came after it. For that reason, Tra le Sollecitudini remains relevant for all those who wish to understand how to acquire the true Christian spirit, how important is one’s engaged participation in the sacred liturgy, and how one may learn to appreciate and appropriate the chant proper to the Roman liturgy.

Father Kurt Belsole, OSB, is a monk of St. Vincent Archabbey and Coordinator of Liturgical Formation at the Pontifical North American College, Vatican City State, Rome. He earned a license from the Patristic Institute “Augustinianum” in Rome while also pursuing studies at the Pontifical Liturgical Institute. Subsequently, he earned a doctorate in theology at the Pontifical Athenaeum of St. Anselm in Rome. His liturgical interests focus principally on the theological foundation for Sacrosanctum Concilium and the authors whose contributions have laid the groundwork for the liturgical reform of Vatican II.

Footnotes

- Pius X, Tra le Sollecitudini, November 22, 1903, Acta Sanctae Sedis (1903-4) 36: 329-339. For the English translation, accessed July 20, 2023, https://adoremus.org/1903/11/tra-le-sollecitudini.

- Pius X, Tra le Sollecitudini, Introduction, November 22, 1903, Acta Sanctae Sedis (1903-4) 36: 331

- Pius X, Tra le Sollecitudini 1, November 22, 1903, Acta Sanctae Sedis (1903-4) 36: 332.

- Pius X, Tra le Sollecitudini 1, November 22, 1903, Acta Sanctae Sedis (1903-4) 36: 388.

- Stefan K. Langenbahn, 23. April 1896 ‒ Anselm Schott in Maria Laach verstorben, accessed July 20, 2023, https://www.maria-laach.de/aktuelles/nachrichten/125.-todestag-von-p.-anselm-schott.html. So significant was Schott’s work and his multiple editions of his people’s missal, that his name has become synonymous with the hand missal used by the people at Mass. It is simply known as a Schott.

- Sacrosanctum Concilium uses the same expression in the following numbers as well: 19, 21, 27, 30, 41, 50, 79, 114, 121, and 124. Sacrosanctum Concilium, Acta Apostolicae Sedis (1964) 56: 105-132.

- Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “active,” accessed July 20, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/active.

- Pius XII, Mediator Dei 23-24, accessed July 20, 2023, https://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/en/encyclicals/document/hf_p-xii_enc_20111947_mediator-dei.html.

- Pius X, Tra le Sollecitudini 3, November 22, 1903, Acta Sanctae Sedis (1903-4) 36: 332; Sacrosanctum Concilium 116, Acta Apostolicae Sedis (1964) 56: 129; Musicam sacram 50a, Acta Apostolicae Sedis (1967) 59: 314; General Instruction of the Roman Missal 41, accessed July 20, 2023, https://www,vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccdds/documents/rc_con_ccdds_doc_20030317_ordinamento-messale_en.html.

- Rembert Weakland, OSB, A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans), 119.