Last month I began this series with an assertion that if spiritual childhood is a necessary disposition for sanctity, then the universal prayer of the Church must have some relation to it. It is rarely, if ever, mentioned that the most famous popularizer of spiritual childhood, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, was steeped in the liturgy. As a religious, she faithfully prayed the Office and had the privilege of daily Mass. Even though they experienced many of the deficiencies of 19th-century liturgical practice (e.g., praying Vespers near noon during Lent), the liturgy always guided and exerted a real influence upon their lives and spirituality.

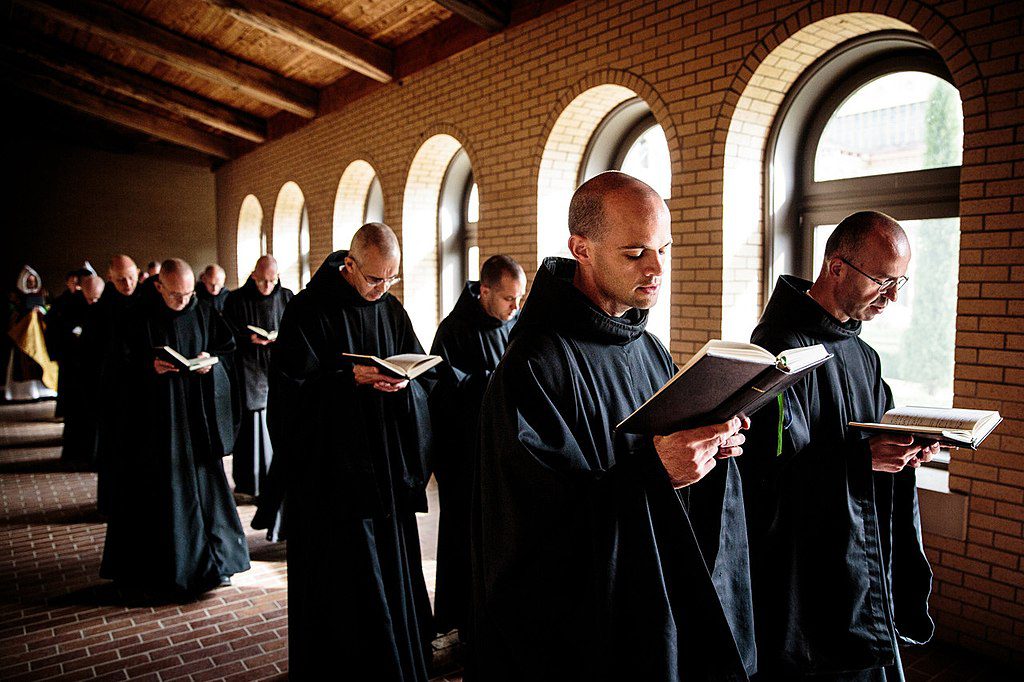

This month, we will be reviewing the relationship between Christian spirituality and monasticism. This exploration is necessary for our overall goal of connecting spiritual childhood to liturgical worship. As I will show, monasticism is focused on the most fundamental tenets and practices of Christian spirituality. As such, it is the premier place to look for the practices and ideals which all Christians should practice, as their state allows, and aspire towards, respectively. The final analysis will demonstrate that monasticism strives, above all else, towards spiritual childhood formed by liturgical worship.

Seek Perfection

You, therefore, must be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect (Matthew 5:48). If you would be perfect, go, sell what you possess and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me (Matthew 19:21).

All Christians who take seriously the Lord’s injunction to be perfect must consider the means necessary for attaining such an exalted end. Childhood, as we showed last month, is a necessary component of sanctification. When searching for the most efficacious formation in spiritual childhood, one ought to examine the spirituality of Religious Life. Also referred to as living out the Evangelical Counsels (poverty, chastity, and obedience), this way of life possesses a greater perfection in its essence than other states. The Fathers of the Council of Trent decreed that “if anyone says that the married state is to be placed above the state of virginity, or of celibacy, and that it is not better and more blessed to remain in virginity, or in celibacy, than to be united in matrimony; let him be anathema.”1 This does not, as the Council affirmed, detract from the honor and dignity of marriage, but it does establish a proper hierarchy of states.

In other words, there is a greater, objective perfection in the Religious Life. Yet, this objective reality makes no conclusive assertion about the individual people within a given state. For example, there are a plethora of ordinary, lay Catholics who died in the odor of sanctity, and there are, presumably and unfortunately, numerous men and women in Religious Life who lived in a state of sin. The Religious Life is more perfect in its essence because the three Counsels combat the three predominant vices. John the Evangelist says that “all that is in the world, the lust of the flesh and the lust of the eyes and the pride of life, is not of the Father but is of the world” (1 John 2:16). Poverty combats lust of the eyes; chastity combats lust of the flesh; and obedience combats the pride of life. Therefore, the very nature of Religious Life provides greater protection against vice and more robust aids to the growth of virtue. Further, the celibate life more closely approximates the life of the blessed in heaven: “For in the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage but are like angels in heaven” (Matthew 22:30). Religious Life is a foreshadowing of heaven in manner distinct from the beauty of married and family life.

If all religious orders live out the Evangelical Counsels, then it might seem difficult to make sense of the near innumerable list of religious orders in the life of the Church. In the first place, St. Paul’s teaching reminds Christians, “Just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ…. For the body does not consist of one member but of many…. If the whole body were an eye, where would be the hearing? If the whole body were an ear, where would be the sense of smell? But as it is, God arranged the organs in the body, each one of them, as he chose. If all were a single organ, where would the body be? As it is, there are many parts, yet one body. The eye cannot say to the hand, ‘I have no need of you,’ nor again the head to the feet, ‘I have no need of you’ (1 Corinthians 12:12, 14, 17-21).

Ordered Members

Each religious order is a member of the Body of Christ, the Church, and has a unique responsibility. Each order has been entrusted with a particular mission to accomplish and possesses its own, unique charism. There is a distinction, however, when considering the nature of monasticism.2 There is something far more universal about monastic life than any other religious order.

The universal nature of the monastic charism is what allows Dom Paul Delatte, a venerable Abbot of the Abbey of Solesmes in France, to declare that there is only one qualification for the monastic and Benedictine life: “An immortal soul—the same baptized—the same from that moment endowed with the supernatural faculties of which contemplation is the proper exercise: this is enough, no more is needed. Does the condition seem simple and easy to be realized? Yet it is the principal one of all, and the fundamental one; it might almost be said that it is the sole condition, given a determined will.”3 Father Louis Bouyer pushes the envelope even further when, in the “Preface” of The Meaning of Monastic Life, he declares, “The purpose of this book is primarily to point out to monks that their vocation in the Church is not, and never has been, a special vocation. The vocation of the monk is, but is no more than, the vocation of the baptized man. But it is the vocation of the baptized man carried, I would say, to the farthest limits of its irresistible demands. All men who have put on Christ have heard the call to seek God. The monk is one for whom this call has become so urgent that there can be no question of postponing his response to it…. In every Christian vocation lies the germ of a monastic vocation. It may develop to a greater or a lesser degree; its very development can take on many different forms. But this germ cannot be smothered without at the same time killing the germ of the Christ-life in us.”4

Another way to view the relationship between monasticism and the Christian life is to see monasticism as the most concentrated form of Christianity. Every dimension of monastic life is, at its heart, the ideal of the Christian life. The principles, the essence, of monastic life are attainable by all Christians. It is the degree of intensity that differentiates the monastic from the ordinary Christian life. Therefore, one must consider the principles of monastic life as applying to the entirety of the faithful.

The Search for God

The most fundamental aspect of the monastic life, the sole telos of its existence, can be summarized in two words: quaerere Deum—to seek God. St. Benedict bids his abbeys to appoint a “senior who is skilled in winning souls, who may watch [the novice] with the utmost care and consider anxiously whether he truly seeks God.”5 Bouyer’s consideration of the titular question, what is “the meaning of the monastic life” arrives at the same conclusion as St. Benedict. He first considers several incorrect beliefs about its meaning such as singing the liturgy, doing penance, studying, etc. Taking each postulation in turn, he demonstrates that each is important to monastic life, but they are not the purpose of monastic life. They are aids to achieving the true purpose. “The search, the true search, in which the whole of one’s being is engaged, is not for some thing but for some One: the search for God—that is the beginning and end of monasticism.”6

It is in this respect that the spiritual practices of monastic life are the most universal and easily attainable. Bouyer criticizes the contemporary paradigm of multiple types of Christian spiritualities. According to him, there is one spirituality—that of the Gospel. There are no “denominations” within the Christian spiritual life. That being said, there are distinct approaches to and applications of this one spirituality. The monastic charism is the most general and universal manifestation of the Christian life. All other charisms, such as Carmelite, Jesuit, Dominican, etc., presuppose the fundamental dimensions of the monastic approach: the search for God. Other charisms pursue their search for God in a specialized manner. We can compare monasticism to a general practitioner in medicine and other Orders to medical specializations such as cardiology, neurology, etc. The latter possess all the necessary components of the former but with additional areas of expertise. Now, the very nature of a specialization means it is not attainable by all. There is a real degree of compatibility that must align between one’s temperament and these specialized orders. Monasticism, on the other hand, is attainable by all regardless of temperament, personality, intelligence, etc.

If the monastic charism is attainable by all Christians who truly seek God, then those who desire to fulfill the exhortation of Christ to become like children ought to examine the fundamental disciplines of the monastic life which are ordered towards that end. The most powerful tools in the search for God are lectio divina (holy reading) and the opus Dei (“work of God”—the liturgy). Delatte points out that “every authentic form of the religious life has for its first object the unifying of the powers of the soul, so as to make them combine for the contemplation and service of God…. In fact, apart from rare exceptions or dispensations, the Divine Office remains the first duty of every religious family.”7 In other words, the chief obligation of every religious order is to pray the Divine Office (Liturgy of the Hours). Unfortunately, “the harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few” (Matthew 9:37). Therefore, “the Church, desiring to secure full success for apostolic or charitable work, puts [these works] into their consecrated hands. Yet, they are then religious ‘with addition,’ in view of work which is superadded and which, though religious because of its motive and relation to God, is not so directly and in its object.”8

Monks, on the other hand, “are religious ‘without addition,’ [they] are religious only…[they] content [themselves] with the affirmation that the proper and distinctive work of the Benedictine, his lot and his mission, is the liturgy.”9 For monks, the Divine Office is not about simply reciting a formulary of prayers, even prayers recited with a devout heart. It is a form of holy performance. Yet, the performance is not for man. Although monks are certain that the “spectacle of the Office worthily celebrated [is] a very effective sort of preaching,” the evangelical potential is not their goal. That possibility is simply an added benefit. Ultimately, the liturgy is about rendering to God his due, and Delatte forcefully declared, “What if the world does not understand this work of prayer and does not appreciate its purpose, except it be from an aesthetic standpoint? …We shall never be tempted so to reduce our life that the world may comprehend it; for our life is what God and St. Benedict and our own free act have made it.”10

Read Into God

The monastic life does not consist of only the liturgy, however. It is complemented by lectio divina—divine reading. St. Benedict exhorts his monks to spend their time which is not devoted to the opus Dei or manual labor in lectio divina.11 Divine reading in the monastic tradition has no other purpose than to “bring us near to God and make us enter little by little into union with Him.”12 This reading is not intellectual in nature. It is “not abstract, cold speculation, nor mere human curiosity, nor shallow study; but solid, profound, and persevering investigation of Truth itself…. It is a study pursued in prayer and in love.”13 Most importantly, lectio divina is prayer. There is much talk nowadays about holy hours, mental prayer, etc. While all true prayer is to be commended, there are serious, possible pitfalls with these modern approaches to prayer.14 In the monastic tradition, however, prayer was seen as much more holistic and all encompassing.

“Apart from the Divine Office (which after all is surely prayer), apart from some moments of private prayer, ‘short and pure,’ which St. Benedict permitted to those who felt attracted to it, all were bidden to devote prolonged study to Sacred Scripture—the book of books—to the Fathers, and the words of the liturgy. So, by ordinance of the Rule, the whole day was to be passed in the presence of God. The method of prayer was simple and easy. It was to forget self and to live in habitual recollection, to steep the soul assiduously in the very beauty of the mysteries of faith, to ponder on all the aspects of the supernatural dispensation, under the inspiration of the Spirit of God which alone can teach us how to pray (Romans 8:26). For sixteen centuries, clerics, religious, and simple lay folk knew no other method of communicating with God than this free outpouring of the soul before Him, and this ‘sacred reading’ which nourishes prayer, implies it, and is almost one thing with it.”15

Historically speaking, the life of prayer has been seen, on the one hand, as much more holistic than a purely intellectual endeavor once per day. On the other hand, prayer was not seen as synonymous with one’s work. Prayer is both an act and a state. It is the guiding principle in our life. Delatte says that “when we were little children, we watched the looks of our mother so as to estimate the value of our actions, and this was the beginning of conscience. The look that we keep steadily fixed on God becomes the final form of our conscience as children of God.”16 The life of prayer, therefore, includes explicit moments of deliberate communication with God but also a prolonged state of continuously living in his presence, beneath his gaze. (We will consider this practice of living in the presence of God and prayer more thoroughly in a future installment.)

Given the greater perfection of the Religious Life and the universally accessible nature of the fundamental tenets of the monastic charism, the disciplines and customs of monastic life are the most logical place to seek out insight about formation in spiritual childhood. Monasticism has long emphasized the discipline of remaining constantly beneath the gaze of God. This includes formal prayer and a prayerful recollection. In order to extend such a state throughout each day, the ancient solution has always been the liturgy.

Next month, we will consider the nature of liturgical worship and its importance in the Christian life. As we will see, liturgical worship consists of far more than Sunday Mass and is critical for every Christian, not just clerics and religious. What does the Church teach about the role of public, communal worship in each individual spiritual life? How can the liturgy of the Church touch the innermost part of the individual soul? How do these realities prepare us for receiving a formation in spiritual childhood? These are the questions that we will dive into next time.

For previous instalments of Steven Hill’s Spiritual Childhood from Liturgical Worship series, see:

Stephen Hill is an MTS student in Liturgical Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Prior to this program, he completed a BS in psychology and an MA in systematic theology. All of his research was inspired by several years of Benedictine formation, and the monastic tradition continues to influence his work. Hill strives to explore the intersection of contemporary psychological research and patristic psychological writings where both fields are most fully manifested: in the sacred liturgy.

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia/Wall Street Journal

Footnotes

- Council of Trent, Session 24, Canon X.

- For the purposes of this article, monasticism includes all the children of St. Benedict: Benedictines, Cistercians, and Trappists.

- Paul Delatte, Commentary on the Rule of St. Benedict (London: Burns, Oates, & Washbourne, Limited, 1921), 370.

- Bouyer, Meaning of Monastic Life, ix.

- Rule of St. Benedict, ch. 58. Et senior ei talis deputetur, qui aptus sit ad lucrandas animas, et qui super eum omnino curiose intendatet sollicitus sit, si vere Deum quaerit.”

- Bouyer, Meaning of Monastic Life, 8.

- Delatte, 134.

- Delatte, 134.

- Delatte, 134.

- Delatte, 136.

- Holy Rule, 48.

- Delatte, 306.

- Delatte, 306.

- The modern approaches to prayer are to a large extent the result of the modern intellectualism which has lost much of the simplicity and purity of the ancients. Further, contemporary Christians seem to equivocate prayer with the intellect rather than also with bodily movements, liturgy, etc. For a full treatment of the issue, see Cecile Bruyere, The Spiritual Life and Prayer: According to Scripture and Monastic Tradition.

- Delatte, 306-307.

- Delatte, 105.