Apostolic custom has it that Mass be celebrated over the relics of the martyrs. A second-century letter on the martyrdom of St. Polycarp records that “we took up his bones, more valuable to us than precious stones and finer than refined gold. We laid them in a suitable place, where the Lord will permit us to gather ourselves together, as we are able, in gladness and joy.” This practice is universally kept by every ancient church, each in its own way. Once Christianity was allowed by the Roman Empire, altars containing the relics of wonder-working saints garnered mass pilgrimages, created trade routes, and quite literally altered the map of Europe.

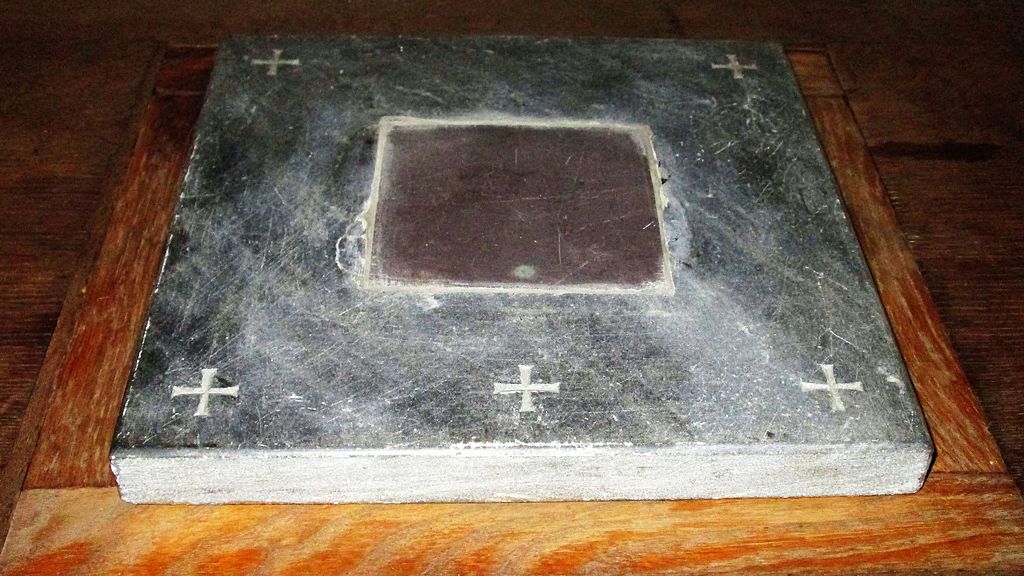

Very quickly there were more altars than tombs of saints, so smaller relics were placed into altars. In permanent stone altars, these relics would be deposited directly into a niche and sealed by the bishop who consecrated the altar. Where the permanence of the altar, or the materials were lacking, an altar stone previously consecrated by a bishop would be used. The exact size and material of this stone varied (although usually eight to 12 inches square), but the stone is always engraved with crosses in each corner and in the center, and there was a niche in one side where relics can be sealed. If the church or altar was no longer suitable for Mass, the stone could be removed and used in another place.

The requirement of relics for the celebration of Mass is long-standing and was not dispensed even in the most extreme conditions. In the 20th century, chaplains offering Mass in camp or in the trenches during both world wars were issued small, paperweight-sized stones, or antimensia, “Greek corporals.” This Eastern equivalent to the altar stone is made of cloth and the relics are sewn to the inside, easier to carry and foldable.

Although these relics are now not strictly required in the more recent rite of The Order of the Dedication of a Church and an Altar, the current Code of Canon Law enjoins: “The ancient tradition of placing relics of martyrs or other saints under a fixed altar is to be preserved, according to the norms given in the liturgical books” (Canon 1237 §2). Even though the law does not strictly require relics for the celebration of Mass, their absence or deliberate omission is wholly unknown to the history of Christian liturgy and contrary to a Catholic sensibility of worship.

An altar stone was consecrated by a bishop, or by his delegate. In practice, many stones would have been consecrated at one time, since the rite is involved. The stones with a niche would be prepared, with the bone relics of at least two (but three is common) martyrs at hand. These relics would be sent by Rome sealed in small packets for this purpose. Paper was used since they were usually smaller fragments of lesser-known martyrs destined for altar stones. Relics intended for public veneration are sealed in round metal reliquaries called thecas, so they can be viewed by the faithful. Some dioceses were issued larger fragments of bones mostly from the Roman catacombs. It is likely that most altar stones from the 19th and 20th century contain relics such as these.

Once consecrated, altar stones could be stored indefinitely and issued to new parishes, especially where circumstances did not permit a solid marble altar. Metropolitans would also store large numbers of altar stones for its suffragans and newly-built side altars.

Identifying an Altar’s Relics Today

Because many stones were consecrated simultaneously, it is often possible to infer the contents of an altar stone, if the contents of many others in the diocese from the same time are known. Many of these altar stones still rest in diocesan archives and can be readily compared to the stones installed in parishes.

Conscientious clergy and layfolk documented whose relics were placed in the stones, sometimes in certificates affixed to the reverse side, though sometimes the names were merely written in chalk. Diocesan or parish archives could also keep these records, but very many have been unfortunately lost through negligence or a revolutionary spirit. If records have been lost, any good conclusion is still guesswork. Stones once consecrated are not opened, since to do so would be to destroy them. The relics inside are doubtless very small, and are sealed with grout. After this consecration the stone constitutes a whole and should never be dismembered. Nevertheless, the stone and its unknown holy ones are a tie to a tradition as old as the Church herself, and a real source of grace for the faithful.

The absence of records that identify an altar stone’s relics is frustrating, but we can do much in our time to prevent this for future generations of Catholics. Although the more recent rite for the dedication of an altar envisions relics being placed inside the altar, beneath the mensa, altar stones (which contain relics whose authenticity are certified by the Church) could be placed inside the altar in addition to other relics to show continuity with the past and give honor to the martyrs contained in them. The newer rite of a dedication of an altar does not, in fact, require the relics be of martyrs (though it suggests it as the first option), but this is the practice of the Church since time immemorial, and it draws a direct connection to the worship of the earliest Christians. Thus, the tradition of using the relics of martyrs should not be dispensed with lightly. New altars dedicated should be documented with many possible redundancies, and in good Latin, so that future generations will have certain knowledge of the church’s own special saints.

Relics housed in the parish church’s altars, whether in past decades or in recent memory, are not a peripheral detail, but are truly at the center of the Church’s worship. They rest in the middle of God’s dwelling place, in his altar where the faithful come to receive him, and at the place where private devotion is joined to the public prayer of Christ to the Father. Relics tie us to the Mass of the earliest Christians and join our sacrifice to that unending choir which praises him unceasingly.

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia