The Second Vatican Council’s constitutions and post-conciliar documents were used to reshape the way Catholic churches looked around the globe. Gone were high altars, prominent tabernacles, altar rails, and the like. However, while the specious “Spirit of Vatican II” has often been cited as a reason to strip churches of their traditional art, furnishings, and architecture, a study of these documents shows that they suggest nothing of the sort—in fact, quite the opposite. This article will focus on the use of altar canopies. Used throughout the Church from St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome to St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, altar canopies architecturally manifest the liturgical and Eucharistic theology of Vatican II and should be encouraged and used in the Church today.

Altar Canopies: An Introduction

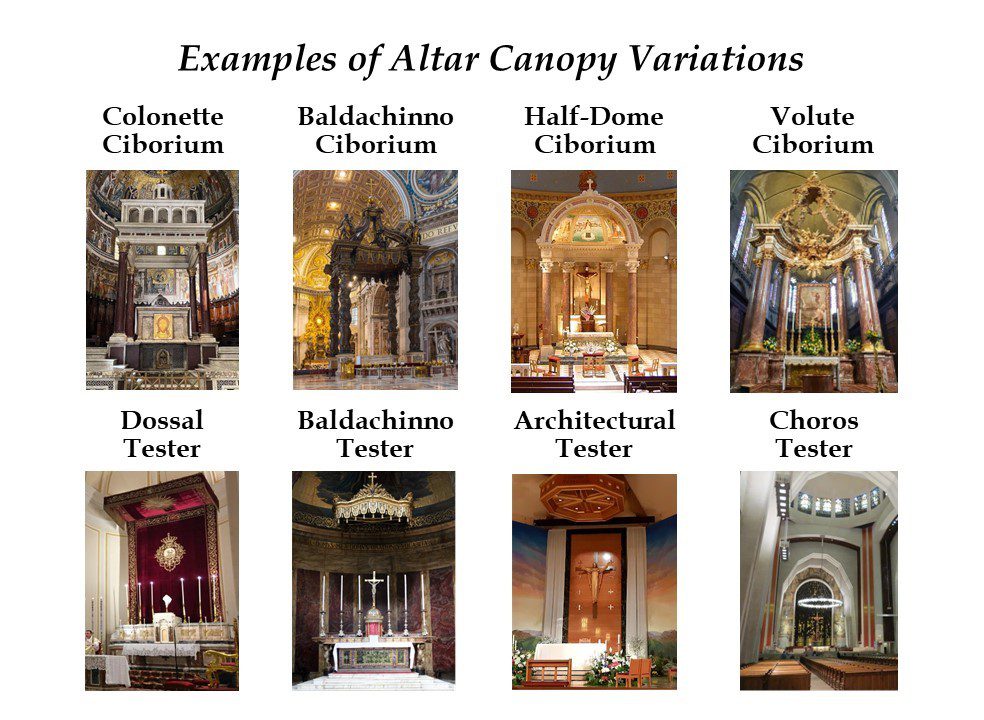

There are two major types of altar canopies: the ciborium magnum and the tester. A ciborium magnum is a canopy that utilizes columns to support architectural or cloth elements above an altar, such as the altar canopy in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. A tester is a canopy without columns that is either hung from the ceiling or cantilevered out from a wall. Both of these types have many subtypes, including the baldacchino. Often confused with the term ciborium magnum, baldacchino comes from the Italian word for Baghdad, the place from which the sumptuous cloth used in altar canopies originated. The term baldacchino properly refers to a fabric canopy, and can be defined to include either a ciborium or tester designed to appear as cloth (such as the ciborium magnum in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome). Along with baldacchinos, there is a wide array of other variations.

The first altar canopy on record was given by Emperor Constantine to the Basilica of St. John Lateran in the fourth century, as recorded in the Liber Pontificalis. Since then, altar canopies have graced church buildings across time and culture. They can be found in every style imaginable, including early Christian (San Clemente, Rome), Gothic (St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, Rome), Byzantine (Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, MO), Arabesque (Eglise Saint-Martin, Pau, France), Art Nouveau (Église Saint-Léopold, Vienna) and Modern (Christ Cathedral, Orange County, CA). This variety reflects the statement from Sacrosanctum Concilium that “the Church has not adopted any particular style of art as her very own; she has admitted styles from every period” (123). Thus, altar canopies can have an appropriate character for any type of church, from ancient to contemporary.

Altar canopies have a great import for the Church today due to the post-Vatican II shift away from the ad orientem high altar towards the now ubiquitous freestanding altar (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 299). With an ad orientem high altar, an architectural back-drop on the wall behind (either a reredos or an altarpiece) is typically used to visually highlight the altar. However, a freestanding altar does not always have such an architectural focal point, and thus has the potential to appear “stranded” in the sanctuary. Altar canopies, unlike a reredos, are (most often) freestanding structures, and are thereby a much more natural pairing with freestanding altars to visually highlight them. Not only do altar canopies prevent freestanding altars from becoming visually lost in the sanctuary, but they also manifest the centrality, prominence, and beauty of the altar and the Eucharist beneath them, thus following the liturgical and Eucharistic theology of Vatican II and later documents.

Liturgy and Eucharist in Vatican II

The Second Vatican Council and more recent documents have all emphatically re-affirmed the centuries-old belief that the liturgy is the central action of the Church. As Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC), the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, states, “the liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed” (10). Because the liturgy is the Church’s preeminent work and her highest fulfillment, it follows that church buildings should be designed around the liturgy, a point explicated by Built of Living Stones, the current guidelines for church architecture from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB): “The church building is designed in harmony with church laws and serves the needs of the liturgy” (28).

Baldacchino comes from the Italian word for Baghdad, the place from which the sumptuous cloth used in altar canopies originated.

Just as the liturgy is the center of the Church, the Eucharist is the center of the liturgy, a fact vigorously affirmed by the Second Vatican Council and other documents. As Sacrosanctum Concilium states, “the work of our redemption is accomplished [through the liturgy], most of all in the divine sacrifice of the Eucharist” (10). Likewise, in the often quoted, but ever salient, line paraphrasing Lumen Gentium, the Catechism of the Catholic Church notes, “The Eucharist is ‘the source and summit of the Christian life’” (CCC, 1324; LG, 11).

Since church architecture should be designed for the liturgy and the Eucharist is the center of the liturgy, it follows that the design of a church should be focused on the Eucharist—and the altar. This focus on the Eucharist as the starting point for all church architecture is echoed by Pope Benedict XVI: “the purpose of sacred architecture is to offer the Church a fitting space for the celebration of the mysteries of faith, especially the Eucharist” (Sacramentum Caritatis, 41).

Liturgical and Eucharistic

In designing a Eucharistic church, the Eucharist and its altar ought to be the central focus of the church building, and the altar should be prominent in its placement, design, and surroundings. “Above all, the main altar should be so placed and constructed that it is always seen to be the sign of Christ Himself, the place at which the saving mysteries are carried out, and the center of the assembly, to which the greatest reverence is due” (Eucharisticum Mysterium, Sacred Congregation of Rites, 24). This is reiterated in Built of Living Stones: “The altar is the natural focal point of the sanctuary” (57).

Beauty must also be considered when designing a liturgical and Eucharistic church. “Beauty, as much as truth and good, leads us to God, the first truth, supreme good, and beauty itself” (Dicastery for Culture and Education, Via Pulchritudinis, 2.2, citing Benedict XVI). God, the author of all beauty and Beauty itself, is reflected in all beauty, whether natural, man-made, or sacred. This is particularly true for the sacred arts, which “by their very nature, are oriented toward the infinite beauty of God” (SC, 122). Thus, beauty is not an optional nicety in the design of churches: “Beauty, then, is not mere decoration, but rather an essential element of the liturgical action, since it is an attribute of God himself and his revelation” (Sacramentum Caritatis, 35, emphasis added). Every part of the liturgy is to be beautiful: the rite, the music, and the art and architecture. “Everything related to the Eucharist,” Pope Benedict says, “should be marked by beauty” (Sacramentum Caritatis, 41).

It is through this beauty that art and architecture become “visible signs used by the liturgy to signify invisible divine things” (SC, 33). While “the Spirit of Vatican II” has been used to whitewash many a church and rip out traditional architecture and furnishings, in reality, the Council declares that “there is hardly any proper use of material things which cannot thus be directed toward the sanctification of men and the praise of God” (SC, 61). St. Pope John Paul II redounds the sentiments of Sacrosanctum Concilium as he writes, “Like the woman who anointed Jesus in Bethany, the Church has feared no ‘extravagance,’ devoting the best of her resources to expressing her wonder and adoration before the unsurpassable gift of the Eucharist” (Ecclesia de Eucharistia, 48).

History and Meaning

Having established that the Eucharist necessitates centrality, prominence, and beauty, we will now look at how canopies have and continue to express these three elements. First, with regards to centrality and prominence, in the secular realm, royal canopies have historically been used from emperors of the Holy Roman Empire to modern European monarchs to symbolize the importance and centrality of the figures beneath them. Similarly, canopies have also been used in Christian art to denote the prominence and sanctity of the person beneath—typically Christ or the Blessed Virgin Mary. These canopies are often depicted in medieval, Baroque, and icon-style paintings, and canopies are also found over tombs and sculptures of saints; in each case, the canopy makes the most important figure visually prominent. Finally, canopies have long been used in the Church as a way to emphasize the sacred office of bishop and pope, and can still be seen in many cathedrals over the cathedra (the chair of a bishop). These canopies denote the hierarchical status of the ministers in the Church and the centrality of their role in persona Christi—in the person of Christ—in the liturgy.

Today, altar canopies are still used to highlight the most exalted status of Christ, the King of Kings, by showcasing the prominence and centrality of the altar and the Eucharist. Altar canopies architecturally manifest the prominence of the Eucharist in the Church, as exhorted by St. Pope John Paul II: “By giving the Eucharist the prominence it deserves, and by being careful not to diminish any of its dimensions or demands, we show that we are truly conscious of the greatness of this gift” (Ecclesia de Eucharistia, 61).

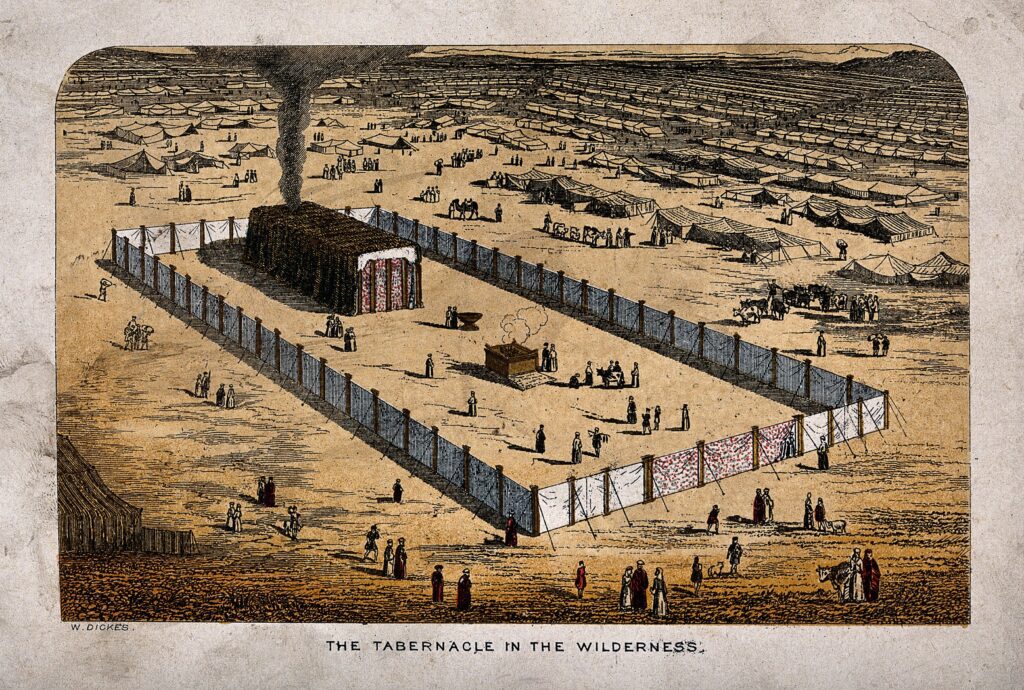

Canopies have also been used to symbolize and connect participants in the liturgy to the beauty of God. One of the earliest canopies associated with religion was the Jewish Tabernacle, the official “housing” of God’s presence among the Chosen People. This tabernacle—in reality, a tent—can be understood as a canopy over the place of God’s dwelling. The Tabernacle was built to exacting specifications given by God to Moses and was made of fine linen, colored cloths, acai wood, gold, and brass (see Exodus 36-39). Its ornate and beautiful construction was not mandated by God out of any arbitrary sense of aesthetics, but because it shared in the beauty of he who is Beauty itself.

In churches today, altar canopies likewise share in the beauty of God. By highlighting God’s presence in the altar and the Eucharist, each of these coverings reminds the viewer that “the author of holiness is Himself present in it” (Eucharisticum Mysterium, Sacred Congregation of Rites, 4). In fact, what goes for the altar canopy also goes for the entire church: “indeed, the nature and beauty of the place and all its furnishings should foster devotion and express visually the holiness of the mysteries celebrated there” (General Instruction of the Roman Missal, 294).

Canopies also bring a different perspective on beauty through their nuptial connotations. Jewish weddings use a chuppah, a special canopy that the bride and groom stand beneath; this tradition is still active in many Jewish communities. Entering beneath this canopy is symbolic of the consummation of the marriage (Guide to Jewish Marriage, Rayner, 19-20). Catholic weddings of the past also used canopies over the couple to-be-wed, particularly in royal ceremonies—a tradition connected to the design of the canopy bed, which serves to highlight the sacredness of the “marriage bed.” Naturally, these nuptial connotations of the canopy derive their beauty from the Christian nuptial mystery, where spousal love is perfected through the imitation of the sublimely beautiful, self-sacrificial love between Christ and the Church (Ephesians 5:21:33). Altar canopies in churches highlight this nuptial symbolism at its height, for the altar is truly the nuptial bed of Christ and his Church, where his Passion, re-presented, is the consummation of this mystical wedding. “Indeed, Christ…loved the Church as His bride, delivering Himself up for her…. He united her to Himself as His own body” (Lumen Gentium, 39). Altar canopies thus express this mystery, reminding us of the profound beauty of the great Sacrament of the Altar.

Beautiful Focus

The Second Vatican Council and post-conciliar documents strongly reaffirm the centrality of the liturgy in the Church, and the Eucharist in the liturgy. They explain and affirm that the Eucharist and the altar are to be the central focus of the church building, prominent, and marked by beauty. Canopies have been and are used to denote royalty, significance, sanctity, nuptiality, and beauty across time and culture. By architecturally manifesting these attributes, altar canopies visually mark the centrality, prominence, and beauty of the Eucharist. With our post-conciliar liturgy and norms, altar canopies ought to be considered and encouraged for liturgical designs in the Church today.