The word “relic” comes from the Latin reliquiae and relinquere, which mean “remains” and “to leave behind,” respectively. There are many passages in Scripture that describe the veneration and use of relics: “And God did extraordinary miracles by the hands of Paul, so that handkerchiefs or aprons were carried away from his body to the sick, and diseases left them and the evil spirits came out of them” (Acts 19:11-12), and many more, including Mark 5:25-34; 2 Kings 2:13-14; 2 Kings 13:20-21; and Exodus 30:28-29. We can see that relics have been recognized as important for millennia. This is not the forum to explain the veneration of relics per se, which has been done quite ably by so many in other places. Our purpose here is to look at the use of relics in altars as a component of the liturgy.

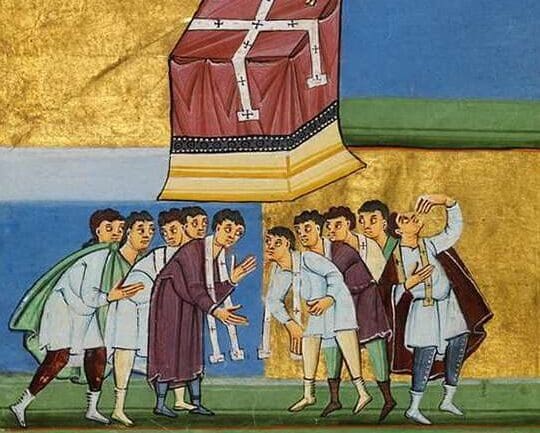

The clearest Scriptural reference to altar relics comes to us in the Book of Revelation: “I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne” (Revelation 6:9). In the heavenly liturgy, the souls of the martyrs are seen below the altar. Even apart from their presence under and inside of altars, the relics of saints (especially martyrs) have been venerated since the earliest days of the Church—liturgically venerated since the fourth century. It was not until the seventh or eighth century that Rome approved the removal of bodies from their place of interment, or their dismemberment, although this was widely practiced in the East before this time.

The primary purpose of a Catholic church is to house the altar, and a church cannot exist without an altar.

The pre-conciliar norms and history are addressed quite thoroughly in J.B. O’Connell’s Church Building and Furnishing: The Church’s Way. A Study in Liturgical Law (1955). There are many aspects of liturgical law that O’Connell describes in great detail, but for our purposes here we shall limit ourselves to citing from Church Building and Furnishing (CBF) regarding the more pertinent norms pertaining to altar relics.

O’Connell points out that the Church regulates matters regarding relics through detailed laws of the liturgy, so as not to leave such an important matter to the whims of individual taste or personal piety, or to one’s own idea of what is properly reverent or attractive. Because a church is intrinsically sacred, “and not merely because sacred acts take place within it, or because it houses the Blessed Sacrament,” it is set aside for divine worship (CBF, 3). This is a fundamental point to keep in mind: the Mass is said in solemn and sacred places, such as over the bodies of the martyrs, and in the church which is explicitly set aside as intrinsically sacred.

The liturgical laws regarding altar relics and the history of how relics came to be an integral part of the liturgy are both significant, because of the importance of the altar. O’Connell says that the primary purpose of a Catholic church is to house the altar, and a church cannot exist without an altar. On this altar, the sacrifice of Calvary is offered in perpetuity, and Jesus Christ is made really, truly, and substantially present. Because of this, a church “is not merely a building in which sacred actions are performed, it is the dwelling-place of God” (CBF, 22).

Relics of History

In the first few centuries of Christianity, private homes were typically the places of worship, and such worship took place in secret to avoid detection by the authorities. Sometimes, Mass would be said in the catacombs or cemeteries, over the grave of a martyr. In the second and third centuries, churches would be built from time to time, but it wasn’t until the Edict of Milan in 313 A.D. that Constantine and others began building the magnificent basilicas, and more churches began to spring up around the empire. Around the sixth and seventh centuries, churches began also to be erected in rural places, whereas before they were primarily built in population centers. There were still private chapels in the homes of the wealthy, and after the sixth century (after the birth of Western monasticism) there were chapels and oratories in monasteries, particularly as it became more common for monks to be priests.

Small tables or small portable pieces of wood or stone laid on a tabletop were initially used as altars for Mass. Usually the altar would be covered with a linen cloth and the paten holding the bread and the chalice of wine; later, the Book of the Gospels may have been placed on the altar as well. Starting around the sixth century, the altar was more commonly permanent and fixed in place, made of stone, and the relics of saints first began to be included in them.

Starting around the sixth century, the altar was more commonly permanent and fixed in place, made of stone, and the relics of saints first began to be included in them.

The relics of the saints, particularly the martyrs, were venerated from the earliest days of persecution, but particularly from the second century on. The remains were not divided into small pieces and distributed, as they so often are now; at that time, the “relics” were the entire bodily remains of the saint. According to O’Connell, it was not until the seventh or eighth century that the pope allowed for the bodies of the saints to be moved from their burial places and for “the dismemberment of bodies to make smaller relics” (CBF, 134). Initially, a crypt or confessio would be under the altar containing the relics of the martyr; around the sixth or seventh century we begin to see the relics entombed in the altar. Around the eighth and ninth centuries, the practice of placing reliquaries on the altar during the celebration of Mass was allowed, and towards the end of that period these reliquaries were sometimes placed over and behind altars, to be venerated.

According to O’Connell, the ninth century was “especially the century of widespread popular devotion to relics of the saints” (CBF, 134). In the period of the ninth to the 14th century which O’Connell calls “The Relic Age,” reliquaries were taking a more and more prominent place on and around the altar. This “relic invasion,” in O’Connell’s words, resulted in changes to the shape of the altar. In order to accommodate the sizeable reliquaries—which had become larger and more ornate to better draw the attention of the congregants—the table went from being square and small, to oblong and larger. From the 14th to 18th centuries, O’Connell notes, “The dominant features of the high altars of this period were size and over-ornamentation, and these features were in keeping with Renaissance ideas, and with Baroque and Rococo styles of architecture” (CBF, 136).

These magnificent altars O’Connell compares to the Masses of Mozart and Beethoven; and, he notes, as the musical Masses were masterpieces for the concert hall but not suitable for Mass, so too these altars may have been artistic masterpieces, “but not conformable to the Church’s idea of another Calvary” (CBF, 137).

According to O’Connell, the relics entombed in the altar were to be authenticated and “primary relics” (the body, part of the body, or bones) of two canonized martyrs. Still, “for validity the relics of one saint suffices, provided they are those of a martyr; but the rubrics and prayers of the rite of consecration suppose the relics of martyrs” (CBF, 152). Nonetheless, there was still some leeway regarding which saints’ relics could be included in an altar, O’Connell says. It is “very becoming” to add a relic of the namesake saint of the church, he says, but adds, “Relics of a beatified person will not do.”

So, how is it that the relics of a saint (particularly a martyr) relate to the Mass? Why, in the early years of the Church, would their tombs make suitable altars, and why would that tradition be carried on by the entombment of relics within altars? Briefly: the sacrifice of the martyrs mirrors Christ’s own sacrifice for our salvation, and it was his sacrifice (continued in the offering of the Eucharist) that gave the martyrs the strength to offer their own lives.

Current Norms

It is a common misconception that every single altar has a relic enshrined in it. As we will see below, there is a great deal of historical precedent (as well as theological propriety) behind the presence of relics in an altar; however, while this practice is still encouraged by the Church, it is no longer a requirement.

Regarding the current norms for altar relics, the General Instruction of the Roman Missal refers to the history of the devotion but does not make the inclusion of relics in an altar a requirement. However, it emphasizes that the relics should be authenticated: “The practice of the deposition of relics of Saints, even those not Martyrs, under the altar to be dedicated is fittingly retained. However, care should be taken to ensure the authenticity of such relics” (302). The Ceremonial of Bishops is more specific about the concern for the genuine article when it comes to relics: “The tradition in the Roman liturgy of placing relics of martyrs or other saints beneath the altar should be preserved, if possible. But the following should be noted: …The greatest care must be taken to determine whether the relics in question are authentic; it is better for an altar to be dedicated without relics than to have relics of doubtful authenticity placed beneath it” (866).

Current norms dictate that relics are to be placed beneath the altar, not into the mensa as was the practice with altar stones.

The Order of Dedication of a Church and an Altar (ODCA) provides further guidance regarding what exactly constitutes an appropriate relic worthy of including beneath an altar, noting that altar relics should be large enough to be recognized as parts of human bodies: “Hence excessively small relics of one or more saints must not be placed beneath the altar” (Chapter 2, par. 5; and Chapter 4, par. 11). The ODCA also makes clear that, in keeping with earlier regulations and historical practice, the preference would be for the relics of a martyr to be included in an altar; however, another saint may be used if relics of a martyr are not available. It is also worth noting that current norms dictate that relics are to be placed beneath the altar, not into the mensa as was the practice with altar stones.

What Does It Mean to Us?

Like all relics, altar relics connect us to the Communion of Saints, but they also serve a further purpose within the liturgical context. Altar relics draw us to the history of salvation and to the hope for eternal glory in the future. For an altar does not have the relics of “the saints” in general but the relics of particular men and women who lived on this earth, lived lives of heroic virtue, and who are now in heaven interceding through prayer for us. This great cloud of witnesses (see Hebrews 12:1), the Church Triumphant, reminds us not only of what we too can achieve through sanctification but also how the sacrifice of Christ, and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, nourished the saints, providing them with the strength and grace to live lives of heroic virtue.

While it is good to pray to “all God’s holy angels and saints,” it is also good to know the particular saint whose remains take up residence in one’s particular church. Among other things, such an awareness can concretize that individual saint’s life, thereby making his or her example more familiar and seem more attainable. Sanctity is not just for a few: it is something we are all called to, and something we all must strive for.

Image Source: AB/Archdiocese of Oklahoma City.

No tour of the history and purpose of altar relics would be complete without at least looking at a few of the more notable examples found in the Church’s rich patrimony of churches. Since best examples tend to be the best teachers, it is through these renowned altar relics that we may better understand how the history and purpose of altar relics can serve to help us encounter Christ in the liturgy.

There are very well-known examples of churches that were constructed with great pains taken to place its altar directly above a saint’s place of repose. The most famous example is certainly St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Construction on the current basilica began in 1506 and was completed more than a hundred years later, in 1626. It was built on the site of the original basilica, which was completed in 360 and was demolished in the early 1500s to make way for basilica which now stands in Rome. But how do we know, with more than 1,700 years having passed, that the remains of St. Peter are buried beneath the basilica that bears his name? In the 1940s, Pope Pius XII approved an excavation of the area underneath the main altar, which determined that the tradition was true: the altar sat on top of (actually, well above) the bones of St. Peter. The Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls is likewise constructed over the remains of the apostle Paul, an unbroken and unanimous tradition that was supported by scientific tests performed in 2009 dating the remains to the first century. In both cases, science seems to have confirmed what faith already knew as certain, at least regarding the veracity of these particular relics. Pius XII’s efforts stand as a testament to the enduring power of the Church’s tradition regarding altar relics.

The saints’ lives were intimately connected with the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the sacrifice of Christ on Calvary offered all over the world.

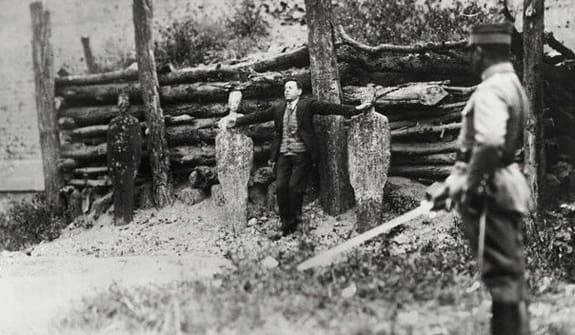

In many places (in particular, it seems, in Italy), the entire body of a saint can be seen on view beneath the altar. Even when it is not in full view, at shrine churches it is not uncommon for a saint’s or blessed’s entire remains to be interred beneath the altar. (Current legislation permits the use of a blessed’s relics, which was not previously allowed.) A very recent case of this can be seen south of Oklahoma City at the Blessed Stanley Rother Shrine. While including the relics of the Blessed in an altar is not the standard, it does help to highlight the purpose behind putting relics of saints within an altar.

This purpose, according to Nikolaus Gihr, in his Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, is to remind us again of Calvary and the Cross: “They who sacrificed their lives and gloriously shed their blood for Christ, should rest at the foot of the altar, whereon is celebrated Christ’s Sacrifice that infused into them the heroism and the strength of martyrdom. The entombing of martyrs in or under the altar designates their close resemblance to the Lamb of God, as it took place in suffering and now consists in glory. When St. Ambrose discovered the bodies of the Martyrs Gervasius and Protasius, he placed them under the altar. In an animated discourse to the people, he said among other things: ‘The triumphal sacrifices are to be placed where the propitiatory Sacrifice of Christ is commemorated. Upon the altar is He that suffered for us all; beneath the altar are they who by His sufferings were redeemed…the martyrs are entitled to this resting place’” (242).

The saints are presented to us by the Church as models and inspiration for how to live as Christians. Nowhere are these saints more effective models for giving glory of God and effecting our own sanctification than in the liturgy. For, the saints’ lives were intimately connected with the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the sacrifice of Christ on Calvary offered all over the world. It is here on this altar that we join with the priest in offering that sacrifice, and where we can seek nourishment, where we can accept the grace we need to become saints ourselves. When the faithful pray before the altar, they know that, thanks to the role that altar relics play in the liturgy, they are joined in those prayers by saints and martyrs who have gone before them, and whose earthly vessels remain behind to remind the faithful of their own eternal destiny.

Paul Senz has an undergraduate degree from the University of Portland, OR, in music and theology and earned a Master of Arts in Pastoral Ministry from the same university. He has contributed to Catholic World Report, Catholics Answers Magazine, Our Sunday Visitor, The Priest Magazine, National Catholic Register, Catholic Herald, and other outlets, and is the author of Fatima: 100 Questions and Answers about the Marian Apparitions (Ignatius Press). Paul lives in Elk City, OK, with his wife and their four children.