With the growth and success of the modern Liturgical Movement, as well as the ad vent of the Atomic Age following the Second World War, there came calls for new and dramatic vernacular developments in the ritual texts for the sacraments of the Church. The material and scientific advances of the modern world—along with the horrors of global industrialized warfare—were deemed to have introduced social and material conditions qualitatively and quantitatively different from any before in human history, and thus required similarly unique and “radical” pastoral innovations to achieve much-needed healing and restoration.1

Many in the English-speaking Liturgical Movement deemed the existing tradition of vernacular rituale content as insufficient for the needs of the contemporary moment. They certainly were aware of the history and widespread use of books like Griffith’s Priest’s New Ritual but were convinced that circumstances demanded new modernized ritual texts using as much vernacular as possible. Prior rituales had organically developed over centuries, producing local and regional differences in vernacular ritual permissions. These “uneven” variations were deemed insufficient for the needs of the atomic era, and those involved in the Liturgical Movement sought to flatten out and streamline things with a new, updated, and more standardized experience. Moreover, they did not just want to expand vernacular—they also wanted to change the texts and ceremonies themselves to be more suitable for modern circumstances and understanding.2

A New Ritual for the UK

In England, the amount of official vernacular text in rituales had been considerably reduced by the dawn of the 20th century—likely as a byproduct of the increasingly “Roman” and “Ultramontane” characteristics of the restored Catholic hierarchy. The 1915 edition of the Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta, for example, contained much less English text than any version published since Challoner’s 1759 edition. Members of the Liturgical Movement in the United Kingdom attempted to produce a modern vernacular ritual to remedy this situation, but their efforts were regularly frustrated by the hesitancy and constant vacillation of the English bishops.

During their annual Low Week meeting in March 1948, the bishops of England and Wales discussed expanding the use of vernacular in the administration of the sacraments and requested that an English translation of the Roman Ritual be prepared for publication. The draft took several years to complete and was finally submitted for their review in 1951. Unfortunately, the mood of the bishops had changed in the intervening time and they demurred on moving forward, saying only that they would “make a decision as to whether they will apply to Rome for permission.”3

In November 1953, the bishops of England and Wales once again changed their minds. They publicly announced that they had decided to petition the Holy See for expanded vernacular in the ritual and launched a project to produce a new translation of the ritual for that purpose. Francis Grimshaw (then Archbishop of Plymouth and later Archbishop of Birmingham and a member on the conciliar liturgical commission) was selected to lead the new U.K. vernacular ritual effort. In a truly extraordinary interview with the Catholic Herald in December 1953, Grimshaw discussed the stakes of the project:

“[Grimshaw] insisted that the arguments for and against the vernacular must be properly weighed. ‘We must realise we shall be losing a great deal. The Latin language of the liturgy is a great possession.’ Asked if he did not think that the Latin liturgy might be preserved by the monasteries whilst the parishes used the vernacular, Bishop Grimshaw replied: ‘No, we can’t treat the liturgy as a national monument and the monasteries as museums for housing it. No, we must face the risk that we may lose something of great value.’ […] I asked how far advanced the work of translating is. The Bishop replied: ‘We should have something ready, I hope, quite soon.’

“His Lordship said that the Latin would be kept for the actual form of the sacrament, but expressed the opinion that if English were admitted for all the surrounding prayers it might be only a matter of time before it was allowed for the forms of the sacrament as well. He spoke again of the need for a realization of what was being lost. ‘There are deep issues here. The Latin formulas can never be entirely abandoned. They express with exactitude and perfection what is the mind of the Church…. If it were all in the vernacular, we should have to change the translation every hundred years as the meaning of the language changed. But we must always try to do as the Church wishes us and it may be that the mind of the Church is changing in regard to the vernacular in the liturgy.’”4

Unfortunately, just a year after this euphoric press coverage, the bishops got cold feet yet again. In December 1954, Grimshaw announced that his translation had been completed but the bishops would only authorize it for private use and were canceling the project for a new official vernacular ritual.5

The 1954 American English Ritual

The journey to a modern vernacular rituale in the United States was initially less tumultuous than that of the British Isles, but ultimately ended in the surprising repudiation and coverup of the agenda of liturgical reform on the very eve of the Second Vatican Council. After years of planning and effort, key members of the Liturgical Movement in the United States (including Jesuit Father Gerald Ellard, Holy Cross Father Michael Mathis, and Bishop Edwin O’Hara) secured the unanimous vote of American bishops in 1953 to publish a modern and national vernacular ritual. After receiving Vatican approval, it was published to great fanfare in December 1954 as Collectio Rituum ad instar appendicis ritualis romani. The rituale permitted almost everything to be said in the vernacular and was expected to transform Church life through improved lay participation and understanding.6

The 1954 American English ritual was also rapidly approved for use in other English-speaking countries around the world. Within just 10 months, it had been authorized in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, Burma, Ceylon, and Malaya. Despite the high hopes of the Liturgical Movement—and heavy promotion of the text—it was not very popular or widely adopted. It seems that the 1954 English ritual was viewed by most priests and laymen as too radical a development and that the alleged widespread demand for modern innovation had been oversold to the bishops, some of whom came to regret their initial support.7 Some bishops restricted its use in their dioceses, while others even forbade its use entirely—despite having voted to approve it just one year prior.

In November 1956 the American bishops secretly voted to put an end to the innovative vernacular ritual and commission a replacement. After several years of confidential work creating a new draft and securing U.S. and Vatican approval, a revised version was quietly published in 1961 which undid many of the novel texts and vernacular permissions of the original. It was a bitter personal defeat for many in the Liturgical Movement—one which they attempted to cover up and which motivated them to fight harder for their cause at the Second Vatican Council.

Ritual Analysis and Findings

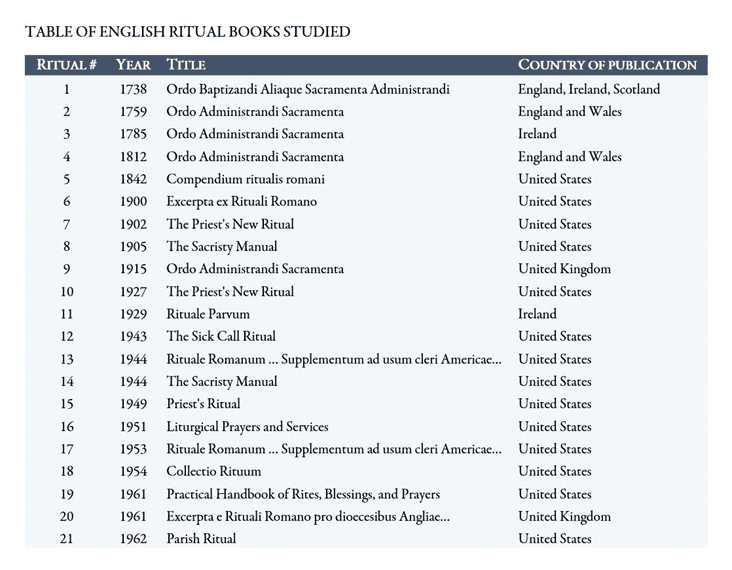

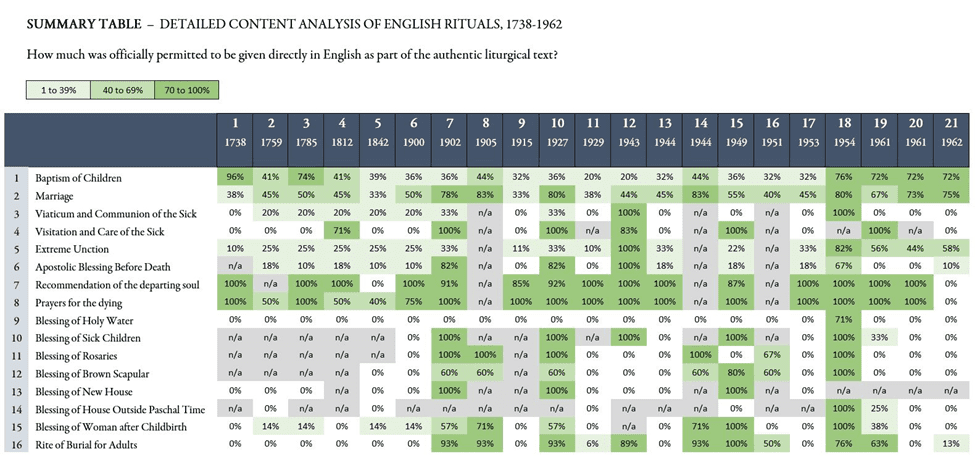

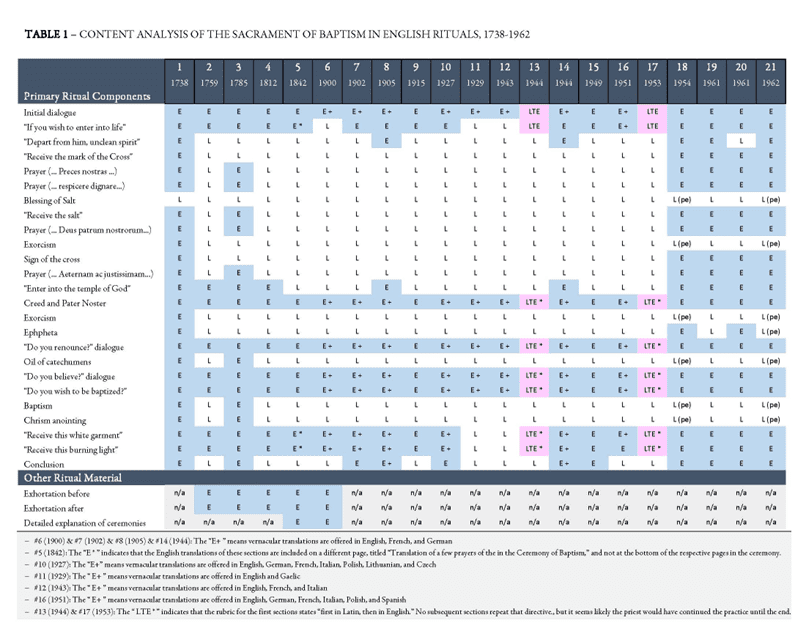

The story of English vernacular rituales is vast and difficult to summarize: it sprawls across two centuries, multiple continents, dozens of titles, and more than 100 printed editions. To allow for meaningful study and easy comparison between these many different editions of the ritual, I examined the content of the ritual books themselves and discretely analyzed how much of the liturgical text was permitted to be given in English instead of Latin on a prayer-by-prayer basis. I selected 21 different rituals between 1738 and 1962 and chose 16 different sacramental rites and blessings from the ritual, (e.g. baptism, marriage, extreme unction, blessing of sick children, etc) for comparison.

The results of this analysis, summarized below, offer a much richer understanding of the centuries-long tradition of vernacular in the administration of the sacraments and permit us to compare different rituals from different countries and decades on a one-to-one basis. Each component of each sacrament and blessing was analyzed to determine if the text was permitted by the ritual to be given in English as the authentic liturgical text.8

There are many interesting observations that can be made based on the summary tables shown above. For example, we can see that the 1785 Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta published in Dublin (Ritual #11) permitted English to be used in 74% of the rite of baptism. This is significantly more than the mere 20% permitted in the 1929 Rituale Parvum also published in Dublin (Ritual #11) but is also more than even the 1961 Excerpta e Rituali Romano (Ritual #20) which had for so long been the project of the Liturgical Movement in the U.K. The significance of the 1954 American English Ritual (Ritual #18) is also apparent—a stark innovation which maximized the amount of vernacular for every item studied—as is the dramatic regression in vernacular content in the post 1961 American rituales (Rituals #19 and #21). For those who wish to explore the findings in more detail, the full prayer-by-prayer content analysis of each rituale, sacrament, and blessing can be found in Forgotten English Rituals, pages 90-94 & 167-186.

Conclusion

This study has revealed the widespread tradition of official English rituale permissions in the centuries before the Second Vatican Council, and documented the origins and failure of the remarkable American English ritual of 1954, for the first time. These are no mere academic or historical curiosities. Rather, this substantially upends previous narratives about the official practices of the Church and the personal experiences of the laity.

It also offers a challenge to modern narratives about the sweeping transformations which occurred within liturgy and life of the Church following the Second Vatican Council. We can now see that the Church had great solicitude towards the laity and regularly offered English vernacular concessions as part of a program of pastoral care. These provisions developed organically and varied according to the local situation and needs and customs of the faithful.

The content analysis of rituales in this study demonstrates a fairly broad and regular availability of English in the administration of the sacraments, featured in more than 100 editions of ritual books published between 1738 and 1962. Thus, the idea of vernacular accommodations and lay participation is shown to be a normal and widespread part of the life of the Church in the centuries before the Second Vatican Council. It is also clear that generous and sustained vernacular usage occurred without the need or demand to alter the traditional ritual texts or the general retention of Latin as the normative position for liturgical practice.

The rituale is an often-overlooked but nevertheless critical part of the Christian mission. Study of the rituale offers us unique insight into the experiences of the laity throughout history—their participation in, and understanding of, God’s action in their life and the life of the Church. It illuminates the grand tapestry of Christian life and practice across the ages and offers context and consideration for the future of the administration of the sacraments. Ultimately, this study can only hope to serve as a starting point for the future research which this subject so richly deserves.

This article is largely a summary of, and in parts is adapted from, material published in Forgotten English Rituals: The Collectio Rituum of 1954 and the untold history of the vernacular administration of the sacraments.

Nico Fassino is the founder of the Hand Missal History Project, an independent research initiative dedicated to exploring Catholic history through the untold and forgotten experiences of the laity across the centuries. He is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and proudly resides with his family in the land of supper clubs, cheese curds, and brandy Old Fashioneds.

Image Source: AB/picryl

Footnotes

- The conviction that old solutions simply would not suffice for the modern man was widespread and applied to every aspect of the Catholic life, from the Mass and the sacraments to the writings of the saints and spiritual advice: “The Imitation is a classic of the spiritual life, but the busy executive or politician who has many meetings to attend in the evening would be confounded by the warning against going abroad. We have the Devout Life written by St. Francis de Sales for lay people, but not the laity who live in an atomic, TV, two-Ford family era.” See Rev. Dennis J. Geaney, OSA, “Some notes on Lay Spirituality,” Worship, Vol. 26, no. 3 (1952), page 114.

- Rev. Gerald Ellard, SJ was one of the most influential members of the Liturgical Movement in America and a tireless advocate for progressive innovation in the rituale among other things. In 1951, Ellard wrote a lengthy and sensational article in the American Ecclesiastical Review which featured a painstaking international survey of rituale modernization efforts. It is Ellard’s opinion that the existing, local traditions of English rituales urgently needed to be replaced by a new standard national vernacular rituale for the United States, one which would receive direct approval by the Holy See and adopt the best and most extensive innovations from countries around the world. See “The Vernacular In Recent Rituals: Ten Years’ Progress.” American Ecclesiastical Review (1951), pp. 325-342.

- Amen, the journal of the American Vernacular Society, May 15, 1951, page 4. Cited in Rev. Gerald Ellard, SJ, “The Vernacular In Recent Rituals: Ten Years’ Progress.” American Ecclesiastical Review (1951), page 335, note 18.

- “Our Own Language For ‘Domestic Rites,’” The Catholic Herald (London), December 11, 1953, page 8.

- This 1954 decision wasn’t the end for the hopes of a vernacular ritual in the U.K. It took two more years to publish Grimshaw’s ritual, which finally appeared as The Small Ritual. Despite the original press releases about it only being a “private” translation for the use of the laity, its own rubrics and other contemporary clerical commentaries prove that it was used as an official ritual book by priests once published. That same year, in 1956, the English bishops performed another about-face and finally petitioned the Holy See for permission for an official national vernacular ritual. Permission was granted to prepare a draft in 1957, and the proposed ritual was submitted to Rome in 1958. On January 14, 1959, the English bishops received the official decree permitting publication and in 1961 the long-awaited official vernacular ritual for England and Wales was published as Excerpta e Rituali Romano pro dioecesibus Angliae et Cambriae edita. In an important and interesting turn of events, following the Second Vatican Council, the 1961 Excerpta e Rituali Romano was cast aside and Grimshaw’s Small Ritual was republished and officially adopted by Australia and England as their official national rituale in 1964. A vernacular ritual for Ireland was published in 1961 (Collectio Rituum ad instar Appendicis Ritualis romani pro Omnibus Diocesibus Hiberniae), which contained far more extensive vernacular permissions than England’s Excerpta e Rituali Romano. Scotland, which had begun its own ritual translation effort in 1959, ultimately adopted Ireland’s vernacular ritual instead of producing their own version because of this fact (a situation which Archbishop Thomas Roberts, SJ described as “the ‘reductio ad absurdum’ of the Scottish bishops asking for the Irish ritual as much better than the English”). This episode offers fascinating historical parallels to the ritual situation two centuries prior, where the Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta for Ireland contained substantially more official vernacular text than Challoner’s version in England.

- The detailed history of the origins, drafting process, approval, and demise of the 1954 American English Ritual is documented with hitherto uncited archival material and told for the first time in Forgotten English Rituals, pp 36-82. The paper also includes a detailed analysis of the 1954 ritual’s vernacular content and how it compared with rituales published before and afterwards (page 92 and pp 166-187). In general, the 1954 ritual permitted everything in English except for the exorcisms and the sacramental forms themselves. A small number of things (e.g. the Sacrament of Confirmation) were retained only in Latin.

- In the words of one influential member of the Liturgical Movement: “If there was not a public clamor of the people for the vernacular, there was a loud and persistent clamor of those clergy and laymen who were well informed. It would be ungracious to refer to St. Benedict’s Rule, where he speaks of the ‘pars sanior’ which may well be a minority.” See Rev. Hans Ansgar Reinhold, “The New Ritual,” Orate Fratres, Vol. 29, no. 5 (1955), page 266.

- I used the following two criteria to determine what was permitted in the vernacular: either the ritual book directly printed vernacular for the priest to say as the official text of that section, or the ritual book printed Latin but stated in a rubric that the prayer could also be said in the vernacular as the official text.