“Throughout the history of the Church, those who fully grasped the place of the Sacraments, in their institution by Christ and in the life of Catholics, always insisted these great gifts of God were for men. The traditional statement, ‘Sacramenta propter homines’ (the Sacraments are for the people), puts it briefly and well. All important, then, in the administration of God’s Sacraments will be the constant consideration of making the Sacraments more readily accessible to all men” (from editorial column “The Holy Father has spoken,” The Catholic Standard and Times, January 16, 1953, page 6).

—————

The cosmos, created good by God and filled to overflowing in his creative generosity, is fractured and disordered because of mankind’s primeval and ongoing rebellion. All of creation—the natural world as well as each human being—stands in need of rehabilitation and reconciliation. Although God alone is able to accomplish this, he has ordained that mankind will be active coworkers, not merely passive spectators, in this work of divine restoration.

These ideas have been at the core of Christian identity since its very beginning, building upon the very earliest revelations that God made to humanity about himself and his vision for human life on earth.1 As the first Christians went out to the whole world, proclaiming the victories of Christ and baptizing in his name, the apostles and their successors used specific ritual ceremonies to confer distinct sacraments and blessings. In this they followed the example of their master, who regularly performed physical, visible, tactile actions as he offered healing, blessing, and transformation.2

From this tradition developed books which recorded the texts and ceremonies for the administration of the blessings and sacraments which originally had been passed down orally. By the early medieval period, these books took different forms: some were large and intended for use on the altar at Mass, others were smaller and designed for the priest’s use during things such as baptisms, confessions, marriages, and the anointing of the sick. These latter books were known under a wide variety of titles but came to be known in general as rituales or “rituals.”3 It is for this reason that the official priestly manual for the administration of the sacraments in the Roman Rite was eventually titled the Rituale Romanum, or Roman Ritual.

A New Study of the Rituales

The priest with sacramental ritual book in hand is thus seen by the Church as “a minister of universal integration” and a “craftsman of the universal rehabilitation.”4 The rituale is an essential part of the Christian life, a critical companion to the clergy, and the context in which the faithful concretely and regularly encounter God amidst the important milestones and quotidian concerns of life.

Until now, it has been a fundamental assumption (in both popular narratives and professional scholarship) that the sacramental rituals of the Western church were administered essentially exclusively in Latin until the changes which followed the Second Vatican Council.5 Because of the Latin language barrier, it is widely believed that the beauty of the ritual texts and the full richness of the sacraments were not appreciated or understood by the laity. Indeed, it was this very fact which motivated the pre-conciliar Liturgical Movement’s pastoral concern and advocacy for the use of vernacular.

New research, however, has upended these assumptions. In an original study of the administration of the sacraments between 1738 and 1962, I discovered that there is a vast and almost totally neglected history of the official use of English in Catholic ritual books. It is now clear that—contrary to essentially all prior narratives—the Church officially permitted English to be used in place of Latin as the authentic liturgical language in the administration of many of the sacraments and blessings in the centuries preceding the Second Vatican Council.6 Rituales containing varying amounts of official English text were sold and authorized for use around the world during these years, including in England, Wales, Ireland, Scotland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and many English-speaking countries in Asia.

The sheer number and variety of rituales with official vernacular content is astonishing. I attempted to compile a limited bibliography of just 25 different ritual titles published between 1738 and 1964, which resulted in a list of at least 128 known editions issued by at least 35 Catholic publishers. Of these, fully 112 editions of 18 of the titles were published before 1954 and therefore clearly predate the modern Liturgical Movement’s efforts at reform. Many of these rituals were quite popular and were issued in multiple editions over several decades. All of this demonstrates that there is a significant history of the official use of English in the administration of the sacraments which deserves to be explored. The article which follows is a short summary and introduction to my research into these “forgotten” English rituales.

Early English Ritual Books

Although I chose 1738 as the starting point for my survey, there certainly are examples of official vernacular text in ritual books published before that date. With respect to English-language rituales, we can still find surviving examples from the medieval period like the Manuale Sarum (British Library Add MS 30,506) which dates to around 1450. This manuale includes a notable amount of official vernacular ritual text given for the priest to say when administering the sacraments. Even the sacramental form of baptism (“I baptize thee in the name of the Father…”) is given as an option for the priest to say in English instead of Latin.7

In the decades following the English Reformation and the increasingly severe efforts to persecute Catholics and destroy English Catholic heritage, only a small number of Catholic ritual books specifically designed for use in the British Isles were published.8 In these editions, almost certainly as a reaction against the vernacularizing and liturgical revision of the Protestants, very little official English text was retained.

In 1730, Richard Challoner departed the English College in Douai to serve as a missionary priest in London. The situation of Catholics in Great Britain had deteriorated significantly in the four decades since the last Catholic king of England, James II, had been overthrown. General social hostility towards Catholics, renewed penal laws and persecution, and pastoral neglect by the “chronically inept…pathetic” Bishop Benjamin Petre had all contributed to the generally difficult and sorry state of the roughly 20,000 Catholics in the London District.9

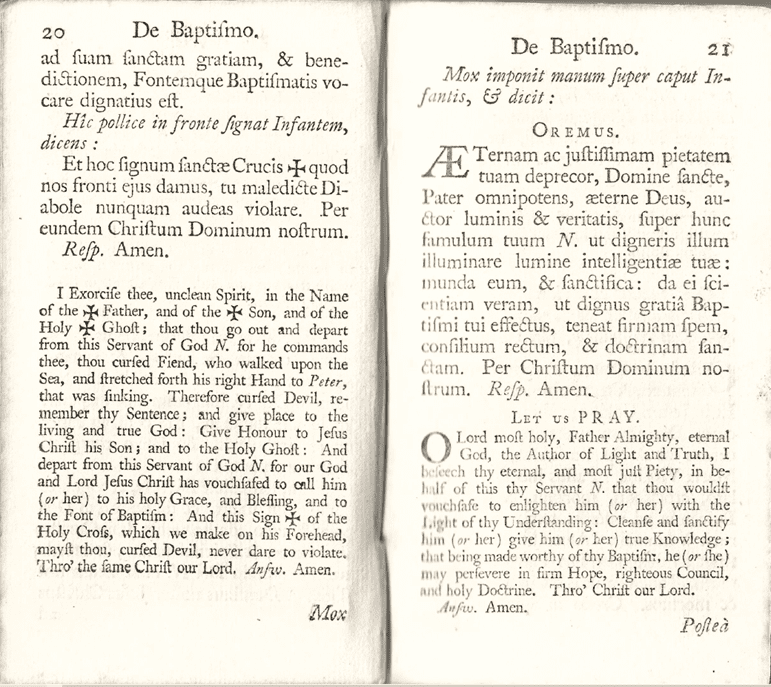

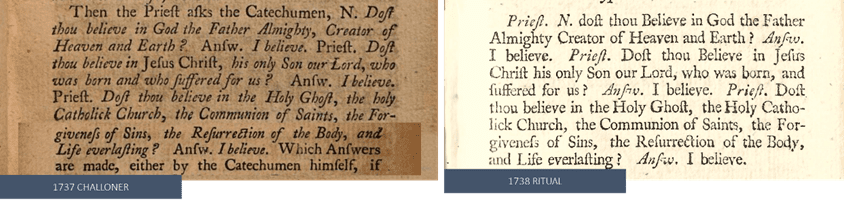

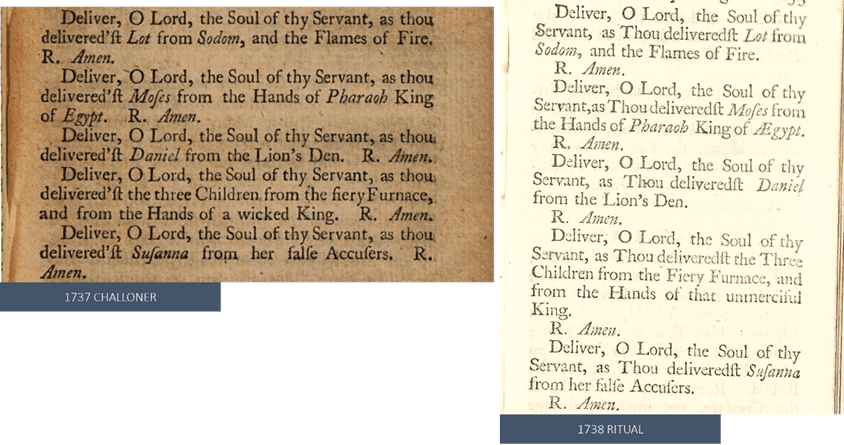

Challoner threw himself quite successfully into the urgent work of rehabilitating the English Catholic community via pastoral care, clerical reform, and administrative management. He also recognized an urgent need for new catechetical, apologetic, devotional, and liturgical books for use by and for the laity. He published a number of popular books in these early years while maintaining a demanding schedule of pastoral ministry. In 1737, he published The Catholick Christian Instructed in the Sacraments, Sacrifice, Ceremonies, and Observances of the Church, a series of explanations on the sacraments and liturgy which included almost the entire text of the ritual translated into English along with running commentary. The next year, with the help of Father Francis Blyth, Challoner brought forth a substantial new edition of the Rheims English New Testament which was printed covertly in London.

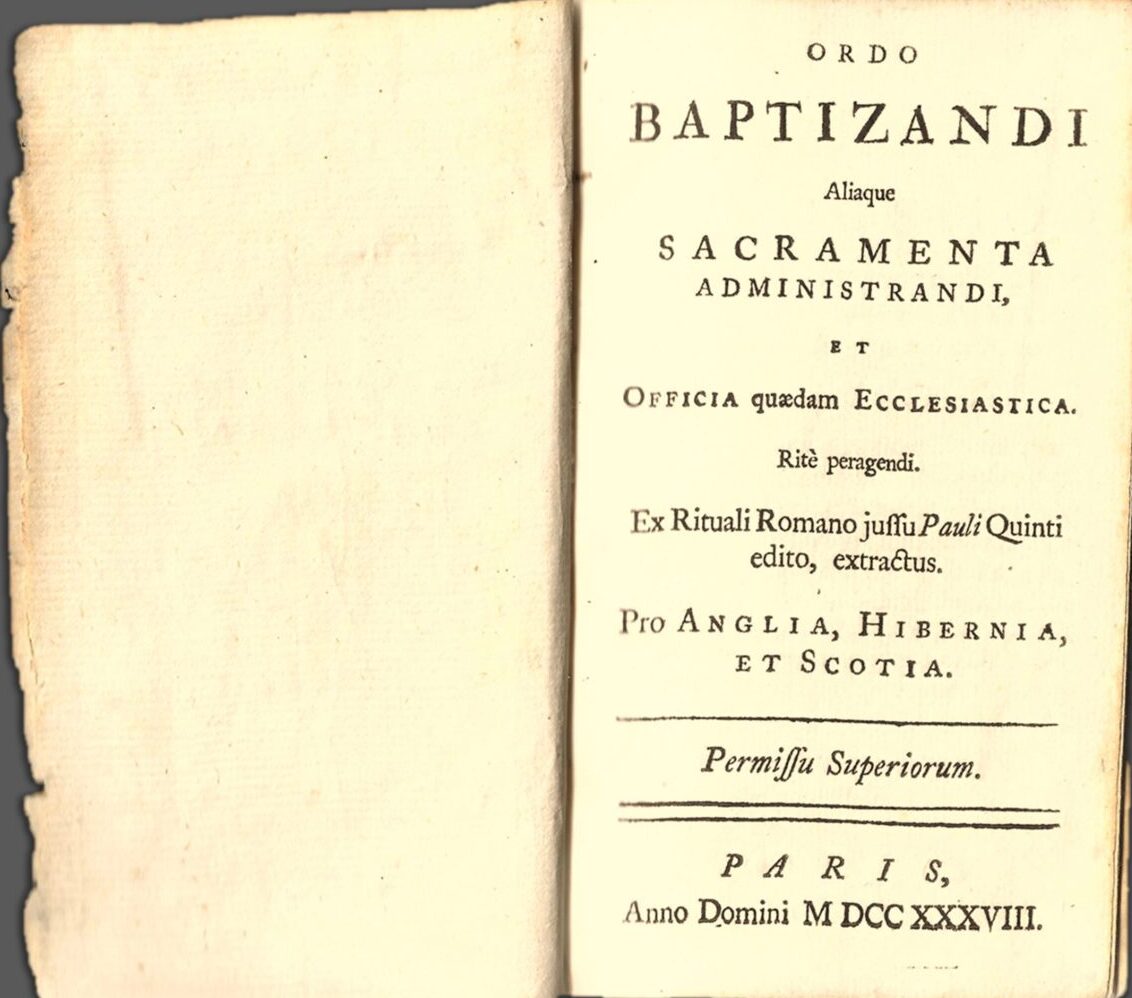

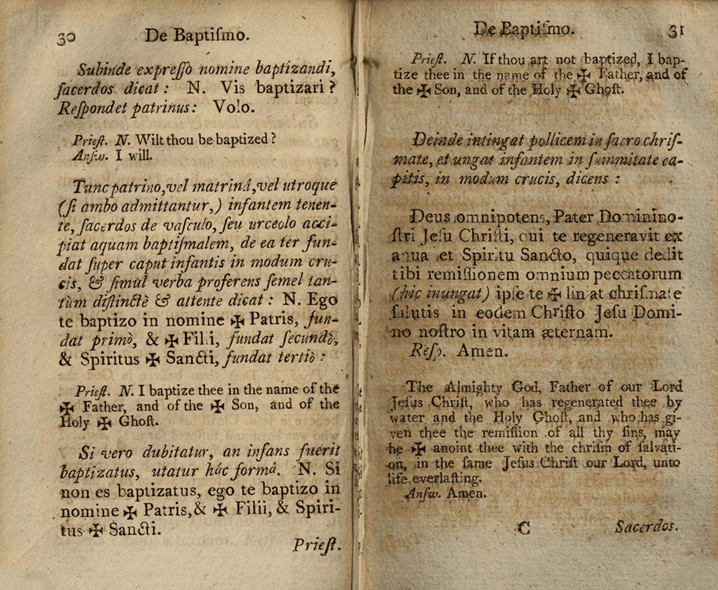

That same year, 1738, another important book for English Catholics was likewise secretly printed in London: an official ritual book for use by priests in administering the sacraments, titled Ordo Baptizandi Aliaque Sacramenta Administrandi. This rituale was significant not only because it was the first ritual book published specifically for use in England since 1686, but also because it contained a remarkable amount of officially permitted English vernacular in the ritual texts. It permitted almost the entire sacrament of baptism to be officially said in English instead of Latin (for some reason the exorcism of the salt alone was required to be given in Latin only, while all other sections were permitted in English). It also introduced an appendix to the ritual which gave the entirety of the “commendation of a departing soul” and the “prayers for the dying” in English.

These innovative English sections printed the vernacular only for the spoken words of the priest and not for any of the instructional rubrics. All other sacraments and blessings were printed exclusively in Latin.10 The use of English in only limited portions of the rituale makes clear that the vernacular was not intended to be of private help for the priest (i.e., in understanding the Latin), but was rather for use in the administration of the sacraments. The 1738 Ordo Baptizandi is thus revealed to be a significant pastoral development with respect to the permissibility of official vernacular usage in the Roman Rite.

Until now, there has been no record whatsoever of who produced this landmark 1738 ritual book.11 I believe, and share here for the first time, that evidence suggests that Challoner himself was responsible for its publication. There are several reasons to think so.12 Most suggestive of all is the fact that Challoner had just completed his Catholick Christian Instructed in the Sacraments in 1737 and portions of his English translations appear to have been re-used exactly (including italicization and formatting) in the vernacular text of the 1738 ritual.

It strains credulity to imagine that, after decades of neglect and inactivity, there was suddenly another significant (but unrecorded) ecclesiastical figure in the London Catholic scene who like Challoner was energetically engaged in book production and pastoral ministry and re-used parts of Challoner’s translations. The re-use of parts of Challoner’s original 1737 translations suggests that he was at least somehow involved in the creation of the 1738 Ordo Baptizandi, even if he was not solely responsible. The near total dearth of surviving information from the first eight years of Challoner’s ministry may help to explain why his involvement managed to remain unknown for so long.13

Challoner’s authorship of the 1738 ritual is additionally supported by the fact that in 1759, after he had been ordained a bishop and took office as Vicar Apostolic for the London District, a new rituale was issued which is known to have been edited and expanded by Challoner himself. Titled the Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta, the work clearly drew on the 1738 Ordo Baptizandi in terms of translations, content, and typesetting.14

Challoner’s 1759 Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta was another milestone for the history of English vernacular in the ritual. In the following decades, several subsequent editions and variants (each sharing the same title) were issued by multiple Catholic publishers. The vernacular content varied somewhat between edition, year, and publisher. For example, an Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta published in Dublin in 1785 featured a substantial increase in official English content compared to Challoner’s 1759 edition.15

English Rituals in America

The fledgling Church in the United States, on the other hand, was without an official or standardized ritual for the first five decades of the Church’s activity in the U.S. But this did not prevent the hierarchy from taking action to provide generous pastoral care to their small and marginalized flock.

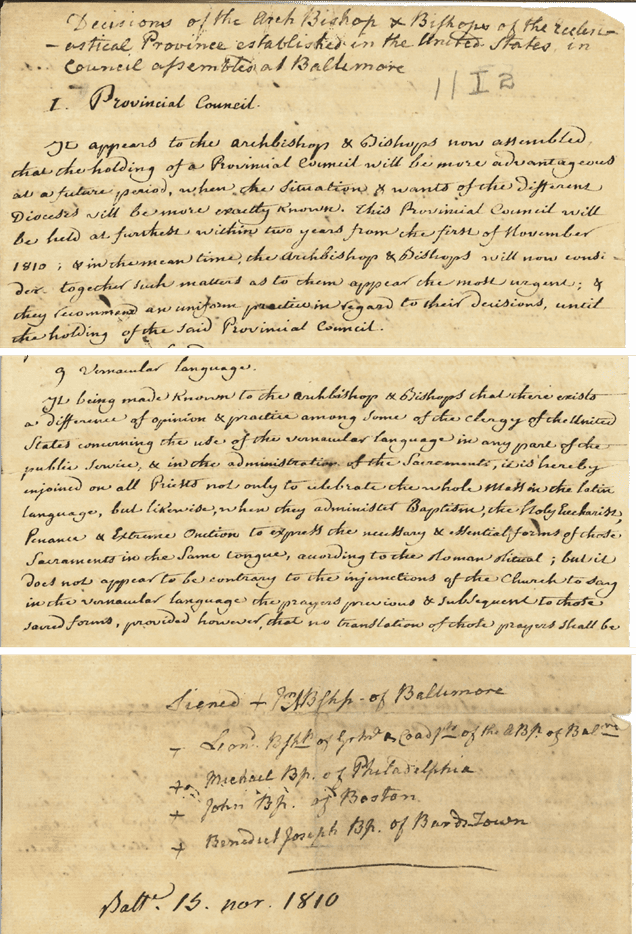

In November 1810, the American bishops issued a series of decrees to regulate various aspects of ecclesiastical life until an official national council could be called. In section nine of the document, the bishops standardized ritual practices throughout the country until such time as an official edition of the ritual could be published for the United States. The bishops authorized an extraordinarily broad use of English in the administration of the sacraments for the United States, allowing for everything to be given in English except the sacramental formulas themselves, and specifically referenced the Challoner translations as an authorized version.16

After several decades of various conciliar decrees and intermittent work, official ritual books for the United States were published in 1842 which contained some vernacular (in English and French) as well as an appendix of vernacular exhortations, instructions, and detailed explanation of the sacramental ceremonies for the laity. They were widely used throughout America and were republished in multiple editions until the dawn of the 20th century.17

In 1902, another groundbreaking ritual with vernacular permissions was published in America. Titled The Priest’s New Ritual, it was compiled by Father Paul Griffith, a remarkable and influential priest known for his innovative (and authorized) use of vernacular for the benefit of the laity.18 Griffith was the pastor of St. Augustine Parish in Washington, D.C., and the ritual was published by John Murphy Company with the personal approval of the Archbishop of Baltimore, Cardinal James Gibbons.

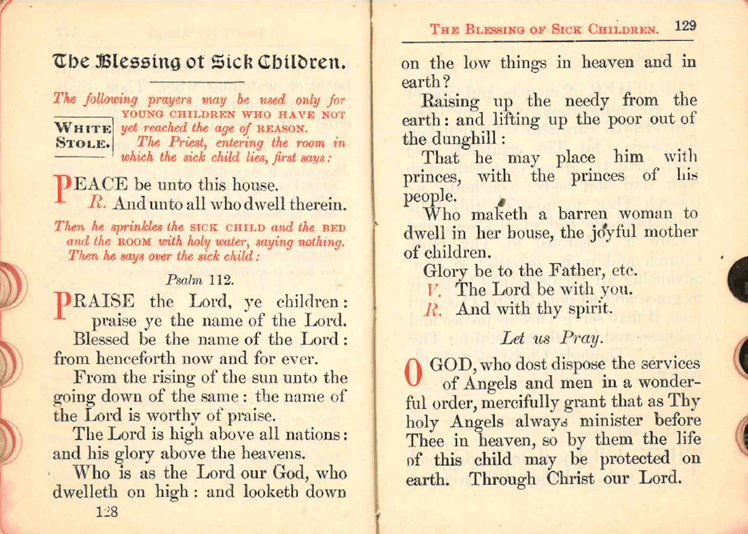

The Priest’s New Ritual was a fascinating compilation. For some sacraments, it contained essentially the same vernacular permissions as previous rituals such as Challoner’s Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta of 1759 or the American Compendium Ritualis Romani of 1842. For other sacraments and blessings, it permitted substantially more of the rite to be given in English instead of Latin. In some cases, like the Blessing of Sick Children, it only printed English text for the priest and did not give the Latin text even as an option!

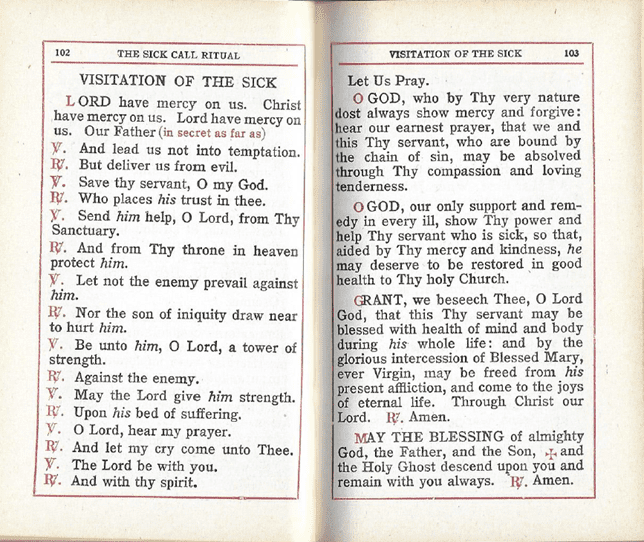

Griffith’s Priest’s New Ritual was wildly popular, going through at least 13 editions across three of the largest Catholic publishers in the United States between 1902 and 1949. Griffith also edited a second ritual, The Sacristy Manual, which offered even more vernacular content in certain rites and was published in at least five editions by two major Catholic publishers between 1905 and 1947. Griffith’s rituals also inspired a number of similar authorized rituals from other publishers (like Macmillan’s Sick Call Ritual and Benziger’s Priest’s Ritual).

All these rituals were permitted for use and sold throughout the English-speaking world. For example, the Compendium Ritualis Romani and Excerpta ex Rituali Romano originally created in the United States were quickly reprinted by Canadian publishers and issued in at least six Canadian-specific editions between 1852 and 1932. Various editions of U.S. rituals, like Griffith’s New Ritual, were also sold directly in Canada for approved use. Likewise, many different editions of U.S. and U.K. rituals were sold throughout Australia for many decades.19 All of this emphasizes that the story of officially permitted English in ritual books extends far beyond the city or nation of their publication.

Watch for part II of Sacramenta Propter Homines: A History of the Sacraments in English in the August edition of AB Insight.

This article is largely a summary of, and in parts is adapted from, material published in Forgotten English Rituals: The Collectio Rituum of 1954 and the untold history of the vernacular administration of the sacraments.

Nico Fassino is the founder of the Hand Missal History Project, an independent research initiative dedicated to exploring Catholic history through the untold and forgotten experiences of the laity across the centuries. He is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and proudly resides with his family in the land of supper clubs, cheese curds, and brandy Old Fashioneds.

Image Source: AB/The Hand Missal History Project/Nico Fassino

Footnotes

- As commented on by Ephrem the Syrian and others, it was before the fall that the command was given to Adam and Eve to go forth from Eden and into the rest of the earth – bringing order, cultivating and husbanding, and filling it with life.

- To heal the deaf and mute man, Christ stuck his fingers into his ears, and spit and touched his tongue, and groaned and spoke a word of command; to heal the blind man, Christ used his spittle to make mud and smeared it onto his eyes; to heal the leper, Christ physically touched him with his hand; to heal a grave illness, Christ bent close and spoke aloud and rebuked the fever (see Mark 7:33, John 9:6, Matthew 8:3, and Luke 4:39).

- Some other common ritual book titles, especially in the medieval period, include: Agenda, Alphabetum Sacerdotum, Manuale, Obsequiale, Ordos (e.g.,Ordo Baptizandi…), Pastorals (e.g., Pastorale, Liber Pastoralis), Rituale, Sacra Institutio Baptizandi, Sacerdotale, Sacramentale, Sacramentorium, Vade Mecum, etc. While there are other books which could properly or colloquially be referred to as “ritual” books (e.g. the Pontificale, Missale, or Brevarium) all mentions of “rituals” or “ritual books” in this article refer to the rituale.

- Rev. Emmanuel Suhard, Priests Among Men (New York: Integrity, 1950), pp. 63-64.

- Many modern articles which seek to explain or defend the changes which followed the Council emphasize the achievement of widespread vernacular translation as a central justification. Likewise, it is common for modern traditionalist critiques of the Council to suggest that widespread vernacular translation was an important factor in the dramatic collapse in sacramental participation and catechesis which followed. There is some existing scholarship on the use of vernacular in some medieval rituals (e.g. Hermann Reifenberg’s 1971 study of rituales in several German dioceses), but the subject of English vernacular rituals has been almost entirely neglected.

- Nico Fassino, Forgotten English Rituals: The Collectio Rituum of 1954 and the untold history of the vernacular administration of the sacraments (2022). Part of the Hand Missal History Project.

- Thanks to the generous permission of the British Library, I have been able to include high resolution photographs of six pages from this manuscript in Forgotten English Rituals, none of which have been publicly available before now. They can be viewed in Forgotten English Rituals beginning on page 162.

- Examples include Laurence Kellam’s Sacra Institutio Baptizandi … juxta usum insignis Ecclesiae Sarisburiensis (first published in 1604) and Manual Sacerdotum, hoc est Ritus administrandi Sacramenta Baptismi … iuxta usum insignis ecclesiae Sarisburiensis (first published in 1610).

- Edwin Burton in his Life and Times of Bishop Challoner, page 69, describes the situation of English Catholics at the time in rather dire terms (and the personal correspondence of Bishop Bonaventure Giffard seems to support this reading). Eamon Duffy, on the other hand, says that “[a] great deal of nonsense has been talked about the ‘catacomb’ existence of Catholics in this period, and the London Catholic community is the clearest refutation of any such notion” (See “Richard Challoner 1691–1781: a Memoir” in Challoner and His Church, a Catholic Bishop in Georgian England, London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1981, page 7).

- The 1738 Ordo Baptizandi also printed portions of the marriage rite, namely the vows and the exchange of rings, in English. These sections had been included in Manuales and Rituales in England since at least the late Medieval Ages, and thus are not innovations made by the 1738 book.

- I am aware of only a handful of places where the existence of this ritual is even noted. The most extensive attempt to discuss the history of this ritual is a 1915 article by Rev. Herbert Thurston, SJ. (“English Ritualia, Old and New,” The Month, Vol. 126, 1915). Thurston could find no information about the editor or circumstances surrounding the creation of the book. He was also clearly startled by the amount of authorized vernacular in the 1738 book, because he conspicuously downplayed the fact and limited his commentary to just three paragraphs.

- Challoner was appointed Vicar General of the London District in 1734 and was thereafter more responsible than he was as a missionary priest for officially providing for the needs of the laity and clergy. This development helps to explain the pastoral impetus for creating the new ritual as well as his authority and standing to do so. Despite the lack of direct bibliographic evidence, the 1738 New Testament (which Challoner is known to have produced) helps suggest Challoner’s involvement in the 1738 ritual due to several interesting similarities. Both were major works published in the same year and both required significant resources, printing house connections, and official oversight and approval by the hierarchy. There is no attribution or reference to Challoner in either the New Testament or the ritual book; both the New Testament and the ritual book were published in London, even though neither of the books indicates this; both title pages simply state “Permissu Superiorum” to indicate that it was officially authorized by the lawful ecclesiastical authority. It is also deeply interesting that Thurston, in his “English Ritualia” cited in note 11 above, admits his private hunch that Rev. John Gother, an influential English cleric known for many important vernacular translations for the benefit of the laity, was somehow involved in the origins of the ritual. Thurston says he has this suspicion despite having no evidence to support this whatsoever and knowing that Gother died more than three decades before the ritual’s publication. This is a minor point but seems to, in a roundabout way, only further bolster my conviction that Challoner created the 1738 ritual, as Gother played a significant role in Challoner’s early life, conversion, and formation.

- “Of Challoner’s life as a simple priest in London we have hardly any information. Scarcely any of his letters written during that time are extant; his work was not such as to be recorded in diocesan archives, and his early biographers pass over eight years of his life, from 1730 to 1738, almost in silence…. we do not even know where he lived[.]” See Edwin Burton, The Life and Times of Bishop Challoner, Volume I (London: Longmans, Green and Co, 1909), pp. 82-83.

- Challoner’s 1759 edition also began conforming the English ritual book more closely with the typical edition of the Rituale Romanum. Although the amount of vernacular in the sacrament of baptism was reduced from the 1738 edition, Challoner retained the concept of the vernacular appendix and introduced a number of exhortations and instructions which were to be read in English before, during, or after the sacraments and blessings. The entire ritual was 140 printed pages; of these, a full 33% (47 pages) are dedicated to the vernacular exhortations and instructions which Challoner composed. It is interesting and important to note that again, like other works, Challoner’s authorship of the 1759 Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta is not indicated in the text itself but is known and attested to by multiple sources.

- The 1785 Irish Ordo Administrandi Sacrament, modelled upon Challoner’s earlier editions of the same title, was commissioned by Archbishop of Dublin, John Carpenter, and featured Irish translations by Charles O’Connor. It would remain in print until at least 1866 across more than 12 editions. Like the other editions already mentioned, these Irish editions of the Ordo Administrandi were not published in dual English-Latin translation for the assistance of the priest. Only certain sections of the spoken ritual text were given in the vernacular, for the use by the priest in the administration of the sacraments, while the remainder of the rituale and all rubrics were in Latin only.

- “9. Vernacular Language—It being made known to the Archbishop and Bishops that there exists a difference of opinion and practice among some of the clergy of the United States concerning the use of the vernacular language in any part of the public service, and in the administration of the Sacraments, it is hereby enjoined on all Priests not only to celebrate the whole Mass in the Latin language, but likewise when they administer Baptism, the Holy Eucharist, Penance, & Extreme Unction, to express the necessary and essential form of those Sacraments in the same tongue according to the Roman ritual; but it does not appear to be contrary to the injunctions of the Church to say in the vernacular language the prayers previous and subsequent to those Sacred forms, provided however, that no translation of those prayers shall be made use of except one authorized by the concurrent approbation of the Bishops of this ecclesiastical Province: which translation will be printed as soon as it can be prepared under their inspection. In the meantime, the translation of the late venerable Bishops Challoner may be made use of.” From Decisions of the Archbishop & Bishops of the Ecclesiastical Province established in the United States in Council assembled at Baltimore, sometimes referred to as Resolutions on Ecclesiastical Discipline (Archives of the Archdiocese of Baltimore #11-I-2). It is unclear exactly what Challoner translation the bishops are referencing, as they do not specify a title. It is possible that they intended to authorize use of editions of the Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta published in England and Ireland, but this seems somewhat unlikely as these ritual books do not contain vernacular translations for everything that the American bishops had just authorized to be given in vernacular. It is also possible that they were referencing Challoner’s The Catholic Christian Instructed in the Sacraments, or something else altogether.

- In 1833, at the Second Provincial Council of Baltimore, the American bishops established a committee to develop an edition of the ritual which was adapted from the Roman Ritual to the needs of the United States, and which would include an appended “English version of the more important parts.” The Third and Fourth Provincial Councils, in 1837 and 1840 respectively, issued additional directives for the creation of the national ritual. This was ultimately published in 1842 under two titles: Compendium Ritualis Romani, ad ususum Diocesum Provinciae Baltimorensis and Excerpta ex Rituali Romano pro administratione Sacramentorum. It therefore appears that official authorization for almost complete vernacular in the ritual in America lasted between 1810 until 1842.

- For example, during the Mass for Palm Sunday in 1905, Griffith sang the Passion directly in English instead of Latin (Evening Star, April 22, 1905, page 9). For more details on Griffith’s biography, see Forgotten English Rituals, page 88 note 237.

- For example: we find Catholic booksellers in Australia selling U.K. editions of the Ordo Administrandi Sacramenta (circa 1860), Murphy’s editions of the Excerpta ex Rituali Romano (circa 1893), Griffith’s Priest’s New Ritual (circa 1926), and Griffith’s Sacristy Manual (circa1945).