The Church’s celebration of the liturgy occurs on two planes: the earthly and the heavenly. Although some limits are placed on our connection with those who once lived in this world but do so no longer—as we find, for example, in the parable of Abraham, Lazarus, and Dives (cf. Luke. 16:19-31)—the expansive view of the Church has always maintained a direct link between those here on earth and those “who have gone before us marked with the sign of faith and rest in the sleep of peace.”1 In his reflection on the topic, the Italian liturgical theologian of the past century, Cipriano Vagaggini, notes the following:

“The liturgy is addressed to every living being in the totality of his being […]. But this totality of the living human being is not fully explored if a person is considered as an individual separate from all other individuals. […] The liturgy prolongs this consideration of the social aspect of every individual in relation to other men even beyond this present life, inasmuch as it establishes a deep union between the faithful who are still pilgrims on this earth and all the just who, since the beginning of the world, have been assembled in God’s presence, the ultimate end of every life.”2

This hoped-for end of human life—beatitude—is brought to the fore in all of the Eucharistic Prayers, but particularly in the Roman Canon. In the Canon we not only find rich details describing the overarching mission of the Church Militant,3 but we see that it also provides a clear presupposition regarding the fulcrum by which the Mass places Christ at the center and, in so doing, connects man on earth to man in heaven, and also to man in via, that is, the souls in Purgatory. Thus, in this final installment of our three-part series on the Roman Canon, our focus will be on the cosmic nature of the Canon and how it helps to join the participants of the earthly liturgy to the participants of the heavenly one. This reflection will examine three aspects of the Canon: 1) the Communicantes; 2) the Supplices te rogamus; and 3) the Memento for the Dead.

Communicantes: In Communion With

In the Communicantes,4 which itself is an extension of the Memento for the Living, we reflect on the “properly chosen representation from the choir of martyrs” to model ourselves on.5 Although there is a sense of parity and fraternity immediately established between us here below and the saints in heaven—a fact that can be established by the very title of this section, “Communicantes” (“In communion with…]”)—we also recall at this moment the awe we should rightly have at that which separates us from them.6 Thus, although we are indeed “in communion with” these fellow Christians, we do not stand with them as equals, but rather we venerate their memories, those whose merits and prayers aid us with God’s protecting help.7

The presentation of the saints in this section is well-balanced, with the Twelve Apostles and 12 martyrs being led by the Queen of heaven, the Blessed Virgin Mary.8 Following the naming of our Lady and the Twelve Apostles, the other martyrs are arranged hierarchically, beginning with five popes—Linus, Cletus, Clement, Sixtus, and Cornelius—and one bishop, Cyprian. Interestingly, in this great prayer of the Roman Church, we find the Carthaginian bishop Cyprian mentioned in the same breath with the Bishops of Rome, which is perhaps both a recognition of St. Cyprian’s influence in the early Church, and also a nod to the universal claims of the Roman Church as head and mother of all. Following this listing of popes and bishop comes six additional martyrs, again arranged hierarchically: Lawrence and Chrysogonus, two clerics,9 and then four laymen comprised of two sets of brothers: John and Paul, and Cosmas and Damian. Whereas Sts. John and Paul were clearly Roman, Sts. Cosmas and Damian were Eastern, who—upon the eventual transfer of their relics to Rome—nonetheless became popular intercessors for the people there.10 Thus, here in the Communicantes of the Canon, we are given critical information about the nature of the Church that is hierarchically arranged in mutual support of all the members of the Body, and that has a universal scope embracing the ends of the earth.

Supplices te rogamus: In Humble Prayer We Ask You

The second section of the Canon being treated in this analysis is the Supplices te rogamus, which occurs after the consecration and as the final component of the anamnetic and oblation sections of the Canon. Here the celebrant bows profoundly before the altar and says, “In humble prayer we ask you, almighty God: command that these gifts be borne by the hands of your holy Angel to your altar on high in the sight of your divine majesty, so that all of us, who through this participation at the altar receive the most holy Body and Blood of your Son, may be filled with every grace and heavenly blessing. (Through Christ our Lord. Amen).”11 In this text we are given an insight into the direct connection that exists between the earthly liturgy and the heavenly liturgy via the “holy Angel.”

The identity of this “Angel,” according to Guéranger, and following the insights of Origen,12 St. Justin Martyr,13 the compiler of the Apostolic Tradition,14 and St. Ivo of Chartres,15 is the only One who can carry such an august sacrifice from this altar to the heavenly one. Guéranger notes the following in this regard: “To what Angel does the Priest here refer? There is neither Cherub, nor Seraph, nor Angel, nor Archangel that can possibly execute what the Priest here asks God to command to be done.”16 From this Guéranger goes on to note that the “Son of God was the One Sent by the Father; He came down upon earth among men, He is the true Missus, Sent, as He says of Himself: Et qui misit me Pater (John 5:37),” and thus it is only this “Angel” who may “bear away haec (What is upon the Altar), and may place It upon the Altar of Heaven.” Thus, the priest “makes this petition in order to show the identity of the Sacrifice of Heaven, with the Sacrifice of earth.”17

This, then, is the key sentiment for us to contemplate at this point in the Canon in which the oblation has already been offered: the connection between the liturgy here below and the liturgy being celebrated in heaven, and the One whose priestly prayer is the basis for everything that we experience at this altar.

Memento etiam, Domine: Remember also, Lord

The final component to our investigation of these cosmic elements within the Canon is the information we can glean from the Memento for the Dead.18 In the Memento for the Dead, following the pattern set by the Memento for the Living,19 the Church Militant is reminded of the care and concern still owed to those members of the Body of Christ who await their final purification to join the ranks of heaven. The text of the Memento provides several points for reflection. The formula begins “Remember also, Lord” (Memento etiam, Domine). In his analysis of this section, Jungmann reflects on whether this “also” (etiam) serves as a possible clue that indicates that the two Mementi—that for the living and that for the dead—were once a single text that was eventually decoupled at a certain point in the Canon’s development. Having these two commemorations joined together, which is the arrangement we find in the other Eucharistic Prayers in the current Roman Missal, has a nice significance, showing the ultimate unity of the Body of Christ, both those living and those who are deceased. However, a poignant message is also found in the separation: since the dead are no longer able to partake in the Eucharist sacrifice, the living provide a surrogate, making petition for the dead as the living themselves prepare to receive the Bread of Angels.20

The faithful are able to do this for the dead because the dead for whom they pray have “the sign of faith” (cum signo fidei). What is the “sign of faith?” It is none other than the seal of Baptism: “it [Baptism] is therefore a guarantee against the perils of darkness and a proud badge of the Christian confessor. The signum fidei gives assurance of entrance into life everlasting provided that it is preserved inviolate. In any case, those for whom we petition have not disowned their Baptism…. The intercession here made for the dead is primarily for those who have departed this life as Christians.”21

And what we ask the Lord at this moment is that those who have been sealed with the sign of faith find “a place of refreshment, light, and peace” (locum refrigerii, lucis, et pacis). The word refrigerium is meant to give the connotation of “coolness,” and, as such, it was originally utilized by those in the “torrid lands of the South,” whether those torrid lands be found in the south of Italy or in Roman North Africa, to indicate the paradisiacal state where the dead share in a sumptuous feast.22 Consequently, we pray that the dead experience the state of blessedness, just as we ourselves prepare for our own experience of blessedness, consuming the sacrificial Victim.

High Society

What we discover in the Roman Canon is nothing short of the blueprint for what the Church, as the Mystical Body of Christ, is called to be: a true society, founded on Christ, and connecting earth with heaven. As de Lubac notes, “the Church which lives and painfully progresses in our poor world is the very same that will see God face to face. In the likeness of Christ who is her founder and her head, she is at the same time both the way and the goal; at the same time visible and invisible; in time and in eternity; she is at once the bride and the widow, the sinner and the saint.”23 In our engagement with the saints, and those who are in the process to be, we find what we, the faithful here on earth, need to continue our own pilgrim journey, nourished by the sacred liturgy that foreshadows the heavenly one to come.

Read part I of Fr. Ruiz’s series on the Roman Canon—“Roman Church, Know Thyself”—The Roman Canon and the Unique Patrimony of the Roman Rite—here, and part II—“Church Militant, know thyself”—The Roman Canon and the Mission of the Church on Earth—here.

Father Ryan Ruiz is a priest of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Currently, he serves as the Dean of the School of Theology, Director of Liturgy, Assistant Professor of Liturgy and Sacraments, and formation faculty member at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary and School of Theology, Cincinnati. Father Ruiz holds a doctorate in Sacred Liturgy from the Pontifical Liturgical Institute of Sant’Anselmo, Rome.

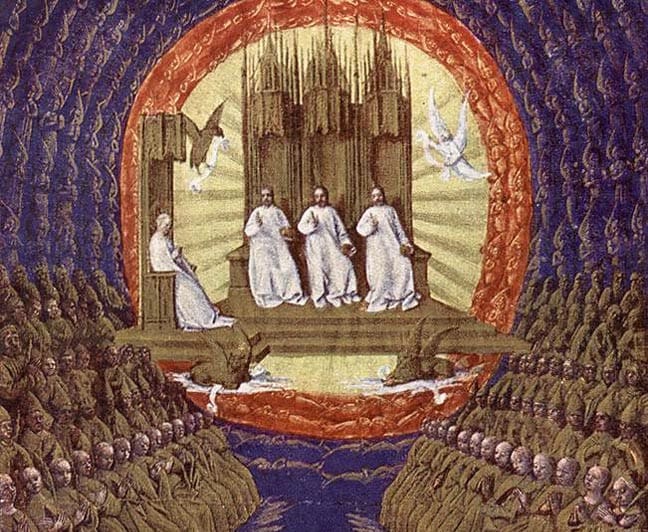

Image Source: AB/WikiArt. The Trinity in its Glory (c.1445), by Jean Fouquet

Footnotes

- The Roman Missal, “The Order of Mass,” n. 95 (Roman Canon – Commemoration of the Dead).

- Cyprian Vagaggini, Theological Dimensions of the Liturgy: A General Treatise on the Theology of the Liturgy, tr. Leonard J. Doyle and W.A. Jurgens (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1976) 335.

- See Part II of this series, “‘Church Militant, Know Thyself:’ The Roman Canon and the Church Militant’s Call-to-Action,” in AB Insight, November 28, 2022.

- In the Ordo Missae, n. 86, this section is given the heading “Infra actionem” (“Within the action”). In this regard, Adrian Fortescue notes that this heading is ultimately related to the special inserts designed for certain feasts. In ancient versions of the Missal, these inserts were printed alongside the prefaces, and so the heading “infra actionem” guided the celebrant to the proper place to insert these in the Canon. Even though these texts are now on the recto side of the pages of our Missals that contain the Communicantes on the verso side, the heading ‘Infra actionem’ remains as a kind of heritage piece. See Adrian Fortescue, The Mass: A Study of the Roman Liturgy (New York: Longmans, Green and Co, 1912) 330–331.

- Josef Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development, Vol. II, tr. Francis Brunner (Notre Dame: Christian Classics, 1950) 172–173.

- Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, Vol. II, 170.

- The Roman Missal, “The Order of Mass,” n. 86: “In communion with those whose memory we venerate […]. We ask that through their merits and prayers, in all things we may be defended by your protecting help. (Through Christ our Lord. Amen.)” (Communicantes, et memoriam venerantes […]. […] quorum meritis precibusque concedas, ut in omnibus protectionis tuae muniamur auxilio. [Per Christum Dominum nostrum. Amen.]).

- See Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, Vol. II, 172.

- Though historical details of St. Chrysogonus’s life are scant or possibly spurious, Jungmann refers to legends developed around the life of this saint that rank him as a cleric. See Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, Vol. II, 173, n. 18. That being said, Fortescue counts him as a layman (see Fortescue, The Mass, 331).

- Mario Righetti, Manuale di storia liturgica, Vol. III, L’Eucarestia Sacrificio (Messa) e Sacramento (Milan: Editrice Ancora, 1949) 310.

- Missale Romanum, “Ordo Missae,” n. 94: “Supplices te rogamus, omnipotens Deus: iube haec perferri per manus sancti Angeli tui in sublime altare tuum, in conspectu divinae maiestatis tuae; ut, quotquot ex hac altaris participation sacrosanctum Filii tui Corpus et Sanguinem sumpserimus, omni benedictione caelesti et gratia repleamur: (Per Christum Dominum nostrum. Amen).”

- See Origen, Homily 3 on Isaiah, in Homilies on Isaiah, tr. Elizabeth Ann Dively Lauro (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2021) 63: “For this reason, he [Christ] is the angel of great counsel; for this reasons, he grew strong, and, becoming strong, he ascended, and the virtues admired him while he was ascending […].”

- See Justin Martyr, The First Apology, Chapter 63, tr. Justin Falls (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1965) 102: “Now, the Word of God is His Son, as we have already stated, and He is called Angel and Apostle; for, as Angel He announces all that we must know, and [as Apostle] He is sent forth to inform us of what has been revealed […].”

- See The Treatise on the Apostolic Tradition of St. Hippolytus of Rome, bishop and martyr, ed. Gregory Dix (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1968) 7: [beginning of the Canon] “We render thanks unto thee, O God, through Thy Beloved Child Jesus Christ, Whom in the last times Thou didst send to us ‹ to be › a Saviour and Redeemer and the Angel of Thy counsel […].”

- See Ivo of Chartres, Sermo V, sive opusculum de convenientia veteris et novi sacrificii, in Patrologia Latina 162, ed. J.P. Migne (Paris, 1854) 535–562. Jungmann notes that here St. Ivo sees the Canon as a renewal of the Day of Atonement wherein the sins of the people are laid on the scapegoat. Thus, “Christ, laden with our sins, returns to heaven” (Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, Vol. II, 233, n. 39).

- Prosper Guéranger, On the Holy Mass (Farnborough, Hampshire: Saint Michael’s Abbey Press, 2006) 96–97. Emphasis original.

- Prosper Guéranger, On the Holy Mass, 96–97.

- The Roman Missal, “The Order of Mass,” nn. 95.

- See, again, Part II of this series, “‘Church Militant, Know Thyself:’ The Roman Canon and the Church Militant’s Call-to-Action,” in AB Insight, November 28, 2022.

- See Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, Vol. II, 240.

- Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, Vol. II, 242–243.

- Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, Vol. II, 244.

- Henri de Lubac, Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man, tr. Lancelot C. Sheppard and Elizabeth Englund (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988) 73–74.