In their 22nd session held on September 17, 1562, the Fathers of the Council of Trent provided the Church with the following insight regarding the Canon of the Mass: “Holy things must be treated in a holy way, and this sacrifice [the Eucharist] is the most holy of all things. And so, that this sacrifice might be worthily and reverently offered and received, the Catholic Church many centuries ago instituted the sacred canon. It is so free from all error that it contains nothing that does not savor strongly of holiness and piety and nothing that does not raise to God the minds of those who offer [it]. For it is made up of the words of our Lord himself, of apostolic traditions, and of devout instructions of holy pontiffs.”[1]

In this short summation of the Church’s most essential liturgical formula, one that the learned Guéranger described as a “mysterious prayer” in which “heaven bows down to earth, and God descends unto us,”[2] the Fathers of Trent not only acknowledged the Roman Canon’s sanctity, but also the sacred sources upon which it was founded: our Lord himself, his Apostles, and his Apostles’ successors. In this description we encounter the hermeneutic in which the Church has always approached the stabilizing force of things liturgical: continuity and tradition.

In this brief essay, the first of a multi-part series on the Roman Canon, we will briefly examine the historicity of the Canon—its sources—and how the Canon, as our current Holy Father, Pope Francis, has recently noted, constitutes one of the Roman Rite’s “more distinctive elements” and, thus, demonstrates a line of continuity between the Mass in its current form and “earlier forms of the liturgy.”[3] The aim of these essays is to provide us with a greater appreciation of the rich patrimony we have received from our ancestors in faith, and how we can better enter into the true spirit of the sacred liturgy.

Gelasian Canon

Our survey of the Canon’s antiquity can most conveniently begin with one of the earliest extant versions of the complete Canon that is found in the Old Gelasian Sacramentary (Gelasianum vetus) of the seventh or eighth century.[4] In this ancient sacramentary the Canon begins with the preface dialogue, followed by a form of the preface that is still preserved in the Missal of Paul VI and John Paul II as “Common Preface II” (Praefatio communis II), and in the Missal of John XXIII as the lone “Common Preface” (Praefatio communis).[5] The Canon then continues with the familiar incipit, Te igitur, and also includes at least one rubrical indication that parallels what is found in the Missale Romanum of 1962.[6]

Thus, there are definite similarities shared between this ancient exemplar and the present Canon. However, there are also unique features that set this version apart from what we have received. For example, after having prayed for the pope and bishop in the Memento for the living, the Canon in the Old Gelasian also calls for prayers to be offered for the king and for all the people of the realm: “Memento, deus, rege nostro cum omne populo.”[7] Another unique feature of the exemplar in the Gelasianum vetus is the inclusion of additional saints in the Communicantes section. Following the articulation of the names of the final two saints listed in the current Canon—Cosmas and Damian—the Old Gelasian’s version then asks for the intercession of Sts. Denis, Rusticus, and Eleutherius, missionaries to Paris, as well as Sts. Hilary, Martin, Augustine, Gregory, Jerome, and Benedict.[8] One can presume that both with the insertion of the prayers for king and kingdom in the Memento for the living, and the inclusion of Sts. Denis, Rusticus, and Eleutherius in the Communicantes, the Gelasianum vetus was merely reflecting its status as a “mixed sacramentary,” one that was thoroughly Roman, but that also began to take on Frankish elements after its reception across the Alps.[9] Another interesting feature of the Gelasianum vetus’ Canon can be found with the words “diesque nostros in tua pace disponas” (“order our days in your peace”) that occupies a place in the Hanc igitur section.[10] Although this phrase is still observed in the present missal, Guéranger notes that this section was most likely added to the earliest exemplars of the Canon by St. Gregory the Great during the time of the Lombard invasion of Italy in the late sixth century.[11] Thus, we can see in this ancient version of the Roman Canon a fixed prayer that nevertheless admitted certain elements that helped the Church meet the societal and pastoral needs of the day.

Ambrosian Canon

Although the version of the Canon found in the Old Gelasian is one of the earliest complete texts to attest to this anaphora’s antiquity, the history of the Canon actually reaches back much earlier. In St. Ambrose’s fourth-century reflections on the Rites of Initiation as celebrated in his Church of Milan, we find a still earlier version of the Canon that contextualizes what is found in the Gelasianum vetus. As we observe in De sacramentis, a series of his mystagogical homilies possibly preached around the year 391, St. Ambrose was as unafraid to adamantly preserve the local customs of his Milanese Church as he was to harmonize the liturgical practices of Milan with those of Rome.[12] This openness to the customs of Rome was reflected in part IV of De sacramentis, where St. Ambrose identifies the words he used for the Eucharistic Prayer.[13]

Although the complete Canon is not illustrated in this mystagogical reflection, and the parts we do find are not always a direct match to what is found in the Old Gelasian’s version, the “differences,” as G.G. Willis notes, “between St. Ambrose’s Canon and the finally settled Canon are less remarkable than their similarities.”[14] The parallels with the Roman Canon in De sacramentis are noted in the following sections: the Quam oblationem (“Be pleased, O God, we pray, to bless […]”), the Qui pridie (the beginning of the Institution Narrative), the Unde et memores (the beginning of the anamnesis), the Supra quae (the continuation of the anamnesis, referencing Abel, Abraham, and Melchizedek), and the Supplices te rogamus (the Communion epiclesis asking for the grace of the Sacrament to be received by all who partake of it).[15]

When looking at the comparison between the Canon in the Gelasianum vetus and that in St. Ambrose’s De sacramentis, we see the gradual tightening of those features that contributed to the “genius of the Roman Rite.” Willis summarized these features through the related insights of Christine Mohrmann and Camilus Callewaert:

“Professor Christine Mohrmann is right in saying that the Gelasian Canon…is, as had already been argued by Mgr Callewaert, a stylistic modification of the forms found in the De sacramentis of St. Ambrose. Its most striking characteristic, she says, is the accumulation of synonyms, and a tendency to amplify, and to make the language more solemn. Paratactic constructions are replaced by either a relative clause, e.g., Fac nobis hanc oblationem by Quam oblationem […], or else by an ablative absolute, as when respexit in caelum is replaced by elevatis oculis in caelum […]. Another tendency is the accumulation of synonyms. This is already a strong characteristic of Roman euchology, which has already made its appearance in the Canon as cited by St. Ambrose, and becomes much more common in the developed Canon.”[16]

Central Prayer

In examining the question of the Roman Rite’s “genius,” to use the phrase popularized by Edmund Bishop,[17] we find in the Canon a unique expression of our Rite’s romanità. Following Bishop’s description of the defining features of the Roman Rite as being its “simplicity, practicality, a great sobriety and self-control, gravity and dignity,”[18] we encounter these details in the Canon’s structure, as well as its rhetorical, theological, and spiritual air that distinguishes it from anaphoras (Eucharistic Prayers) observed in the other Rites of the Church, both in the East and in the non-Roman West.[19]

As the Church continues to reflect on the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council, and as she takes to heart the recent exhortation of the Holy Father about her role as a “custodian of tradition,” a wonderful place to begin this reflection of the Church’s engagement with continuity and tradition is that central prayer of the Mass that unites the Church Militant with the Church Suffering and the Church Triumphant in the Priestly Sacrifice of the Son to the Father in the Spirit. In the upcoming installments of this series we will engage in a deeper study of the Canon, of its various features, and how we as clergy and faithful can profit from the richness of this ancient euchology that still has pride of place in our Roman Rite.[20]

Father Ryan Ruiz is a priest of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Currently, he serves as the Dean of the School of Theology, Director of Liturgy, Assistant Professor of Liturgy and Sacraments, and formation faculty member at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary and School of Theology, Cincinnati. Father Ruiz holds a doctorate in Sacred Liturgy from the Pontifical Liturgical Institute of Sant’Anselmo, Rome.

Notes:

Council of Trent. Session XXII (September 17, 1562), Ch. 4, in Henrich Denzinger, Enchiridion symbolorum definitionum et declarationum de rebus fidei et morum (Compendium of Creeds, Definitions, and Declarations on Matters of Faith and Morals, 43rd Edition, ed. Peter Hünermann, Robert Fastiggi and Anne Englund Nash (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2012) 418-419, n. 1745. ↑

Prosper Guéranger, The Liturgical Year, Vol. 1. Advent, tr. Laurence Shepherd (Fitzwilliam, NH: Loreto Publications, 2000) 78. ↑

- Pope Francis, Epistula accompanying the motu proprio Traditionis custodes (16 July 2021). English translation, www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/letters/2021/documents/20210716-lettera-vescovi-liturgia.html, accessed 17 July 2021. ↑

- Most scholars place the terminus a quo from after the pontificate of Pope St. Gregory the Great (†604) and the terminus ad quem to before the pontificate of Pope St. Gregory II (715-731). See Cassian Folsom, “The Liturgical Books of the Roman Rite,” in Handbook for Liturgical Studies, Vol. I, Introduction to the Liturgy, ed. Anscar Chupungco (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, A Pueblo Book, 1997) 245-314, esp. 248. See also Eric Palazzo, A History of Liturgical Books: From the Beginning to the Thirteenth Century (Collegeville: Liturgical Press/A Pueblo Book, 1998) 45. ↑

Liber sacramentorum Romanae Aeclesiae ordinis anni circuli. Sacramentarium gelasianum, ed. Leo Cunibert Mohlberg, Leo Eizenhöfer, Petrus Siffrin, Rerum Ecclesiasticarum Documenta, Series Maior, Fontes IV (Rome: Herder, 1960) 183-184, nn. 1242-1243. Henceforward abbreviated as GeV (Gelasianum vetus) with the identifying reference numbers being the margin numbers found in the critical edition. ↑

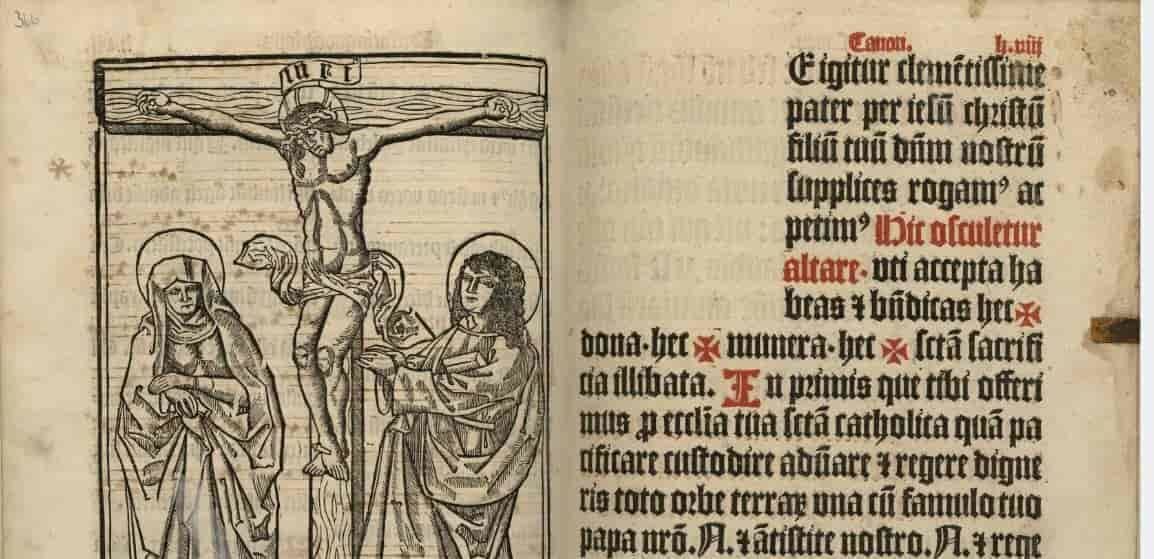

This is found in GeV 1244 where we find five signs of the cross rubrically prescribed at the words, “[…] uti accepta habeas et benedicas + haec dona +, haec munera +, haec sancta + sacrificia i[n]libata + […]” (“that you accept and bless + these gifts +, these offerings +, these holy + and unblemished sacrifices +”). This parallels, though does not exactly correspond, what we find in the Missale Romanum of John XXIII (1962), where only three signs of the cross are called for at this point in the Canon, at the words “haec + dona, haec + munera, haec + sancta sacrificia illibata.” In the Missale Romanum of Paul VI and John Paul II, no additional gestures are called for. ↑

GeV 1244. Interestingly, in referencing the bishop the GeV uses both “antistite” and “episcopo” – “una cum famulo tuo papa nostro illo et antestite [sic] nostro illo episcopo” – instead of only “antistite” as found in the current Canon. ↑

GeV 1246: “Dionysii[,] Rustici[,] et Eleutherii[,] Helarii[,] Martini[,] Agustini[,] Gregorii[,] Hieronimi[,] Benedicti.” ↑

Although a sacramentary devised for presbyteral use in the tituli of Rome, especially – as scholars surmise – in the Church of San Pietro in Vinculi (St. Peter in Chains), the Gelasianum vetus nevertheless exhibits elements of cross-pollination with Frankish customs then beginning to abound in the Roman Rite. Cf. Folsom, “The Liturgical Books of the Roman Rite,” 249, and Palazzo, A History of Liturgical Books, 45-46. ↑

GeV 1247. ↑

Prosper Guéranger, On the Holy Mass (Farnborough, Hampshire: St. Michael’s Abbey Press, 2006) 81. ↑

See De sacramentis III, 5, regarding the practice in Milan of the post-baptismal washing of feet: “We are aware that the Roman Church does not follow this custom, although we take her as our prototype, and follow her rite in everything.” English translation from Edward Yarnold, The Awe Inspiring Rites of Initiation: Baptismal Homilies of the Fourth Century (Middlegreen, Slough: St. Paul Publications, 1971) 122. ↑

De sacramentis IV, 21-22, 26-27. ↑

G.G. Willis, A History of Early Roman Liturgy: To the Death of Pope Gregory the Great, Henry Bradshaw Society, Subsidia 1 (London: The Boydell Press, 1994) 23. ↑

Cf. Ibid., 24. See also Uwe Michael Lang, The Voice of the Church at Prayer: Reflections on Liturgy and Language (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2012) 111-113. Here, Father Lang gives a synoptic table outlining more clearly these parallels. ↑

Willis, A History of Early Roman Liturgy, 27-28. Cf. C. Mohrmann, “Quelques observations sur l’évolution stylistique du canon romain,” Vigiliae Christianae IV (1950) 1-19; C. Callewaert, “Histoire primitive du canon romain,” Sacris Erudiri II (1949) 95-110. ↑

Edmund Bishop. The Genius of the Roman Rite. Strand (England): The Weekly Register, 1899. ↑

Ibid., 15. ↑

In particular, the Gallican and Mozarabic. ↑

General Instruction of the Roman Missal 365a. ↑Image Source: AB/Tom Erik Ruud/The National Library.

Image Source: AB/Tom Erik Ruud/The National Library.