The extension of Roman liturgical practice north of the Alps happened for a variety of religious, cultural, and political reasons. Above all, Rome, the hallowed place of the martyrdom of the Apostles Peter and Paul and the see of the successor of Peter, attracted many pilgrims who were deeply impressed by the liturgical celebrations they witnessed and were keen to see some of their elements introduced back in their homelands. An important landmark was Pope Gregory the Great’s sending of Augustine and his monastic companions to England in the late sixth century. The highly successful evangelization of the Anglo-Saxons and its wider cultural impact were specifically linked with Roman observances, strengthened the position of the papacy, and prepared the ground for Anglo-Saxon missionaries and scholars to work on the continent in the following century.

The Rise of the Carolingian Dynasty

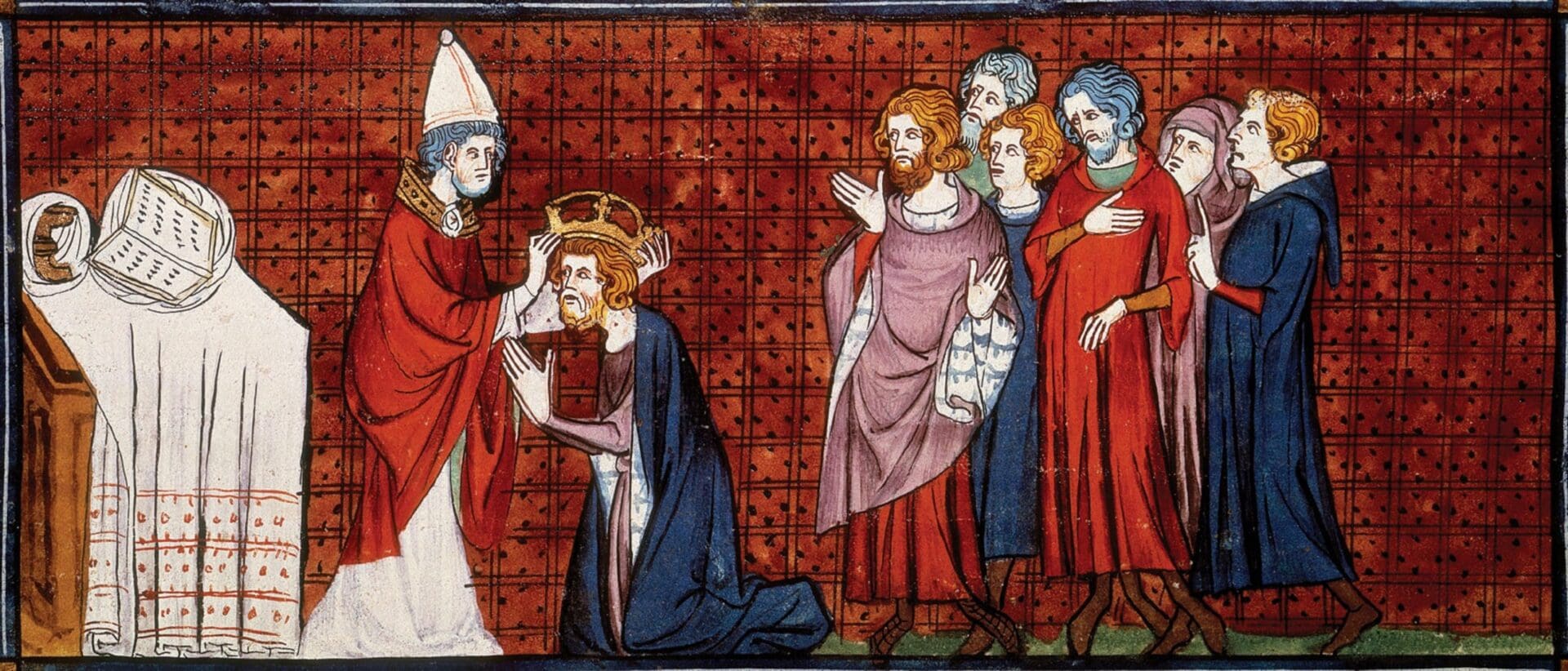

The eighth century saw the rise of the Carolingian family to the Frankish throne, and their strong alliance with the papacy was to shape the history of Europe.[1] Pepin the Short, king of the Franks from 751 to 768, introduced Roman chant with the support of leading bishops in his realm. This was not just a matter of musical preference but had profound implications for the choice of liturgical texts and the structure of the liturgical year. Thanks to what James McKinnon called the “Frankish absorption and transformation of the Roman chant,” the repertory we know as “Gregorian” was created.[2]

Pepin’s son and successor, known as Charles the Great or Charlemagne (born c. 742, king 768, crowned emperor 800, died 814), resumed the work of his father with great energy. Charlemagne understood himself as a Christian Caesar who would renew the Roman Empire in union with the papacy. He not only enlarged the Frankish empire until it extended from central Italy to the North Sea and from the Spanish March to the Elbe river, but also promoted a program of reform aiming at “the Christianization of society through education.”[3] Charlemagne’s legislation is shot through with admonitions and appeals for a reform that is meant to promote “unanimity with the Apostolic See and the peaceful harmony of God’s holy Church.”[4] While this demand included the use of Roman liturgical books, diverse sacramentaries continued be used, combining Roman-Gregorian, Roman-Gelasian, and Gallican material.

At the same time, the Carolingian reform gave the Mass a ritual structure and shape that would essentially be retained for over a millennium. Frankish liturgists adapted Ordo Romanus I (see Part VII) as the standard and measure of the celebration of Mass to the local conditions and customs of their cathedrals and churches. In doing so, they ensured that the solemn pontifical liturgy remained the normative exemplar, in which all other celebrations of the Eucharist participated to a greater or lesser degree.

Personal and Emotive Liturgical Expression

The Frankish adaptation of the Roman Rite has been described as a shift towards a more personal, emotive understanding of and approach to the liturgy. The Gallican tradition shows a strong sense of spiritual introspection and of personal involvement in ministering at the altar. This tendency can be identified in the incorporation of specific prayers of a distinct style or register into the already existing structure of the Roman Mass. Such prayers known as apologies (apologiae) are composed in the first person (singular or plural) and make the bishop or priest celebrant enter into a personal dialogue with God, in which he acknowledges his sinfulness and expresses his fervent hope of receiving divine mercy in the form of a worthily offered Mass.[5] These prayers tend in a more penitential direction, which corresponds with the increasing focus on the priest as acting in the person of Christ in the re-presentation of the sacrifice of the Cross.

Silence and Liturgical Prayer

The earliest clear evidence for a partial recitation of the Eucharistic prayer in a low voice is found in the East Syrian tradition, in Narsai’s Homily on the Mysteries from the late fifth or early sixth century. The inaudible recitation of large parts of the anaphora by the celebrant also spread to Greek-speaking churches by the middle of the sixth century. Gallican and Mozarabic liturgies also witness to the practice of saying prayers quietly, while the cantors would sing. In the Ordines Romani, we can identify a development from the understanding of the Canon of the Mass as a “holy of holies,” into which only the Pontiff could enter, towards its recitation submissa voce.

We also need to keep in mind that, before the age of electrical amplification, when the pope celebrated Mass in one of the larger Roman basilicas, such as the Lateran, or St Peter’s in the Vatican, it would have been impossible in most parts of the church to follow the prayers he recited or chanted at the altar. Even in a smaller church, the audibility of the liturgical prayers would be limited. Just as there were visible barriers, such as the relatively high cancelli separating various precincts of the church’s interior, and a ciborium over the main altar, likewise the physical dimensions of the church interior created an acoustic separation between the pope and his assistants at the altar and the faithful in the nave.

Local Reform and Practical Reach

The physical settings of liturgical worship in central and western Europe at this time were for the most part very simple. There was a considerable gap between the cathedrals of episcopal towns and the humble chapels associated with rural settlements, with the churches of religious communities somewhere in between. At the same time, even plain buildings could have a relatively ornate interior, especially around the altar. Churches in economically prosperous areas were certainly provided with liturgical objects made of precious materials.

Synodal decrees and ecclesiastical capitularies from the early Middle Ages insist that priests should know and understand the texts they recite, celebrate the Divine Office diligently, care for their churches, look after relics, make sure bells are rung to call the faithful to prayer, and so on. Likewise, synods and individual bishops exhort the faithful not to talk idly when they are in church, but to be attentive and prayerful during liturgical services—and not leave before the Mass has ended.[6] The elevated language of liturgical prayer raised obstacles for comprehension even among Romance-speakers. Lay literacy was very limited in the early Middle Ages, and collections of devotional prayers (preces privatae) were the privilege of a small elite.

When it came to musical resources, there must have been a considerable gap between episcopal and monastic centers, and the rural churches that served the majority of the people. Complex chants melodies required trained singers and only simple responses and refrains would allow for popular involvement. Still, Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis assumes that the people join in the acclamations at Mass and explicitly mentions the Sanctus.[7] At any rate, it would be anachronistic to evaluate liturgical life in the Carolingian period by modern criteria of active participation, which are largely based on speaking roles. The efforts to raise the dignity and splendour of divine worship, along with the emphasis on a broad education in the essentials of the Christian faith, no doubt increased the lay faithful’s ability to enter into the celebration of the sacred mysteries.

Conclusion

The success of the Roman-Gregorian liturgy throughout Western Europe was not simply a result of its imposition by royal and ecclesiastical authority, but also owes much to its religious and cultural appeal, as well as its ability to integrate Gallican elements. It was not rare in liturgical scholarship of the mid-20th century to present this synthesis in disparaging terms and to call for a return to pure and pristine Roman tradition (a principle that was implemented in the liturgical reforms after Vatican II only in parts).

We are now in a better position to appreciate the enrichment that the Carolingian reform brought to the Roman Mass, and I would suggest that, because of its (necessarily) slow and gradual pace, its dependence on local initiative, and its focus on education (first of the clergy and, through them, of the whole people), it is a reform that merits the disputed epithet “organic.” As will be discussed in the next instalment, at the beginning of the second millennium, this process came full circle and the mixed Roman-Frankish rite was established in the papal city itself.

For previous instalments of Father Lang’s Short History of the Roman Rite of Mass series, see:

- Part I: Introduction: The Last Supper—The First Eucharist

- Part II: Questions in the Quest for the Origins of the Eucharist

- Part III: The Third Century between Peaceful Growth and Persecution

- Part IV: Early Eucharistic Prayers: Oral Improvisation and Sacred Language

- Part V: After the Peace of the Church: Liturgy in a Christian Empire

- Part VI: The Formative Period of Latin Liturgy

- Part VII: Papal Stational Liturgy

- Part VIII: The Codification of Liturgical Books

Notes:

A good overview of the period is offered by Joseph H. Lynch and Phillip C. Adamo, The Medieval Church: A Brief History, 2nd ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2014), 72-84. ↑

James McKinnon, The Advent Project: The Later Seventh-Century Creation of the Roman Mass Proper (Berkeley – Los Angeles – London: University of California Press, 2000), 3. ↑

Susan Keefe, Water and the Word: Baptism and the Education of the Clergy in the Carolingian Empire, Publications in Medieval Studies, 2 vol. (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2002), vol. I, 2. ↑

Admonitio generalis, c. 80. ↑

Such “apologies” are also known in the Byzantine tradition and the oldest known example from the Divine Liturgy is the prayer “No one is worthy” (Οὐδεὶς ἄξιος), may go back to the late seventh century. See Alain-Pierre Yao, Les “apologies” de l’Ordo Missae de la Liturgie Romaine: Sources – Histoire – Théologie, Ecclesia orans. Studi e ricerche 3 (Naples: Editrice Domenicana Italiana, 2019), 37-42. ↑

See Andreas Amiet, “Die liturgische Gesetzgebung der deutschen Reichskirche in der Zeit der sächsischen Kaiser 922–102”, in Zeitschrift für schweizerische Kirchengeschichte 70 (1976), 1–106, 209–307, at 103 and 269. ↑

Admonitio generalis, c. 70. ↑