Editor’s note: We are pleased to announce a new series of articles on the history of the Roman Rite Mass, by Father Uwe Michael Lang. Happily, this first of the series coincides with the celebration of the institution of the Eucharist, recalled each year at Holy Thursday’s Mass of the Lord’s Supper. Subsequent entries will run primarily in our monthly e-newsletter, AB Insight. (If you don’t already receive this monthly missive in your inbox, sign up at Adoremus.org.)

The Roman Rite is by far the most widely used liturgical rite in the Catholic Church. The form of Mass most people are familiar with today has been shaped decisively by the Apostolic See of Rome in contact and exchange with other local churches over the centuries. This series of articles is intended as an overview of the development of the Roman Rite Mass until the present day. Understanding this rich and complex history will help not only the clergy in their sacramental ministry but also laypeople in participating fruitfully in the liturgy of the Church.

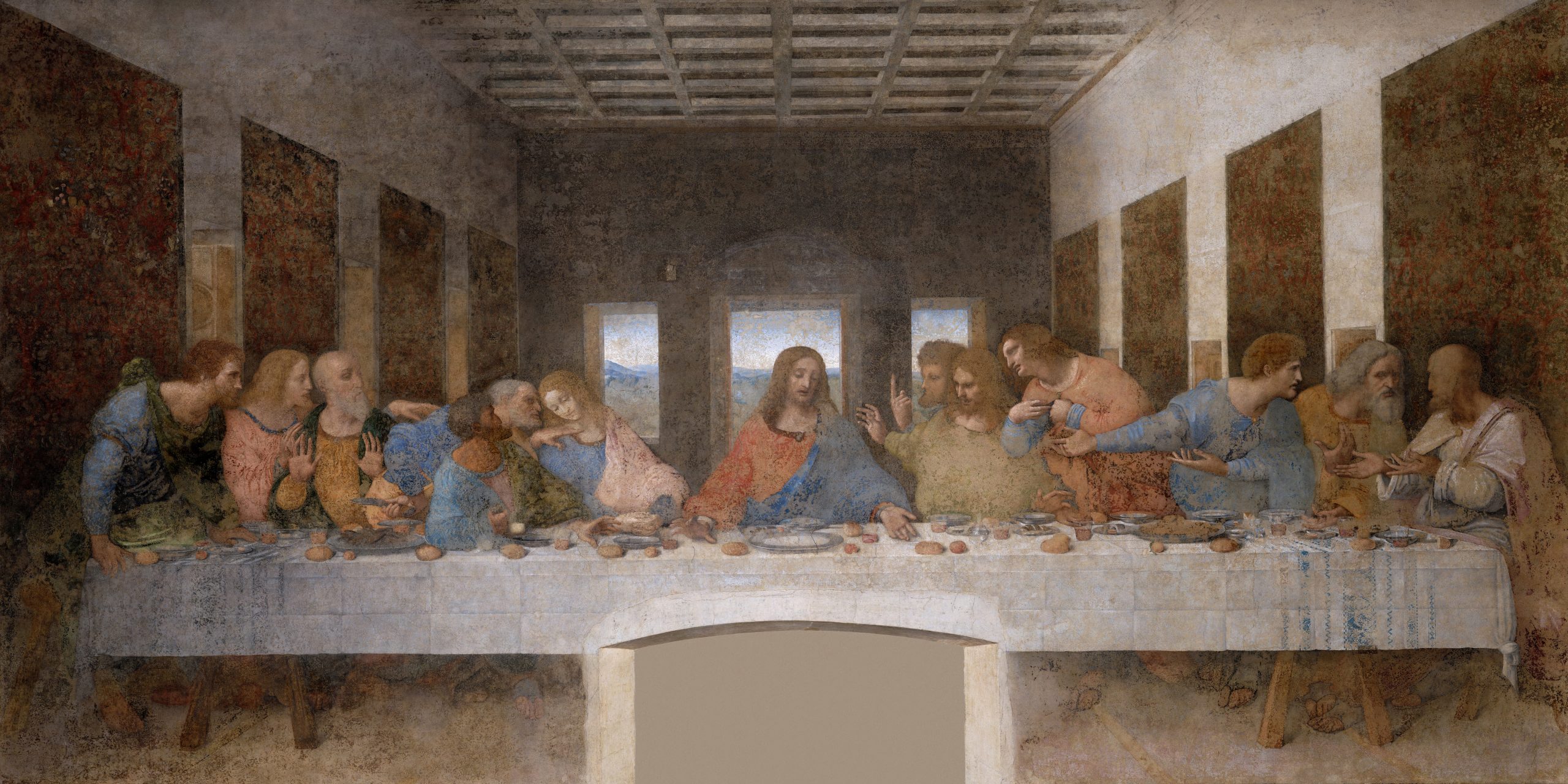

A conventional history of the Eucharist would begin with the Last Supper and its formative impact on early liturgical practice. Thus, liturgical historian Josef Andreas Jungmann, S.J., asserted in his classical work Missarum sollemnia: “The first Holy Mass was said on ‘the same night in which he was betrayed’ (1 Corinthians 11:23).”[1] However, recent studies have presented a highly diverse picture of primitive Christianity, and the origins of the Eucharist have been subjected to radical questioning. Thus, the leading liturgical scholar Paul Bradshaw sees in the narrative of institution as recorded in the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) a tradition superimposed on the original account of a simple meal.[2] On the other hand, many New Testament exegetes are more confident about the essential historicity of the Last Supper tradition.[3]

A Night to Remember

While the meals Jesus held during his public ministry offer a broader context for the Last Supper,[4] there are several features that make it unique, above all its immediate proximity to his Passion. Unlike other meals recorded in the Gospels, this one is limited to the Twelve, his closest circle of disciples. The setting is not that of open table-fellowship, but a private room that would have been provided by a wealthy patron. The words and actions of Jesus are embedded in this meal, but they stand out and transform it in an entirely unexpected way.

The actual words Jesus spoke over the bread and over the cup of wine make them signs anticipating his redemptive Passion.

According to the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus celebrated the Last Supper with his disciples on the first day of unleavened bread, in the evening (Matthew 26:17, 20; Mark 14:12, 17; Luke 22:7, 14). Since Jews reckoned the day from sunset to sunset, this evening meal was held on the 14th day of the Jewish month Nisan, the date of the Passover feast, after the lambs had been sacrificed in the Temple in the afternoon. This day would be a Thursday, with the crucifixion taking place on Friday, “the day before the sabbath” (Mark 15:42; also Matthew 27:62; Luke 23:54), the 15th of Nisan. The Synoptic narratives thus present the Last Supper as a Passover meal.

The Fourth Gospel presents a different chronology: while it agrees regarding the days of the week, it clearly implies that Jesus was crucified as the day of preparation for the Passover was drawing to its close (John 18:28; 39; 19:14). Significantly, Jesus dies on the cross at the time when the lambs are slaughtered in the Temple for the celebration of the Passover meal in the evening. The Last Supper was thus held on the evening before Passover, and it would not have been a Passover meal. Still, it would have been in close proximity to it, as explicitly stated in John 13:1, and thus bears many marks and meanings of the Passover. Unlike the Synoptics, John does not describe the meal itself, but focuses on Jesus washing of the disciples’ feet (13:2-11).

AB/Wikimedia. Agnus Dei, by Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664)

Passover Part II

From the historian’s point of view, it seems more likely that the Last Supper was not a Passover meal—a position supported by Joseph Ratzinger—Benedict XVI with reference to the work of John P. Meier.[5] Even so, at any Jewish formal meal, nothing was to be eaten without God first being thanked for it. At the beginning of the Last Supper, some form of meal blessing (berakah) would have been said. We can also assume the ritual use of bread and wine, the latter being a particular sign of a festive occasion. However, what Jesus said and did at the occasion was unprecedented and cannot simply be derived from any Jewish ritual context. The actual words he spoke over the bread and over the cup of wine make them signs anticipating his redemptive Passion.

Jesus was fully aware that he was about to die, and he anticipated that he would not be able to celebrate the coming Passover according to the established Jewish custom. Therefore, he gathered the Twelve for a special meal of farewell that would include the ritual use of bread and wine, the latter being a particular sign of a festive occasion. While the reference to “this Passover” in Luke 22:15-16 could mean the meal Jesus was holding with the Twelve, it could also point to the new reality he was about to institute in anticipation of his Passion. The decisive moment of the meal was not the customary Passover Lamb (which even the Synoptics do not mention), but Christ instituting the new Passover and giving himself as the true Lamb. This would be in harmony with 1 Corinthians 5:7 (“Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed”), and it is also implied in John 19:36, where the sacrificial rubric of Exodus 12:46 (also Numbers 9:12) is applied to the crucified Jesus: “You shall not break any of its bones.” Christ himself is the sacrificed Lamb and the new Passover is his death and resurrection, which fulfil the meaning of the old Passover. The content of this new Passover is signified in celebration of the Last Supper when Jesus gives to his disciples bread and wine as his body and his blood.

Promise of Blood

The biblical institution narratives fall into two distinct groups: Mark 14:22-25 is close to Matthew 26:26-29, both referring to the blood of the covenant of Mount Sinai (Exodus 24:8), whereas Luke 22:14-20, which has an affinity to 1 Corinthians 11:23-27, highlights the new covenant of Jeremiah 31:31. While the Fourth Gospel does not report the institution of the Eucharist, it would appear that John 6 (especially verses 51-58) presupposes it. The Lord’s words of institution fulfill all five “primary criteria” for sayings or deeds attributed to the historical Jesus, as developed in New Testament scholarship, especially the criterion of “multiple attestation” (that is, confirmed by more than one account)—not just of a general motif, such as “Kingdom of God,” but of a precise saying and deed.[6]

There is no compelling reason not to accept the origin of the words of institution in Jesus himself.

While there is thus a strong plausibility that the dominical words at the Last Supper, as transmitted by Paul and the Synoptic Gospels, represent the ipsissima vox of Jesus (the “kind of thing” he would have said), the variations in the four accounts pose the question of the ipsissima verba (what exactly he said). Allowance needs to be made for development of the oral tradition and the work of a final redactor. There would seem to be a wide consensus among biblical scholars that Jesus indeed broke bread, gave it to his disciples and said, “This is my body,” thus anticipating the violent death he was about to suffer. Neither the Hebrew nor the Aramaic language use the copula “is,” but it can be safely assumed that Jesus identified the broken and shared bread with his body and hence with the voluntary offering of his life.

The words over the chalice are usually considered to have undergone some post-Easter editing from different theological perspectives. The pre-Pauline and Lukan version, evoking a “new covenant,” mitigates the scandal to Jewish ears of drinking blood. However, the reference to Jeremiah 31:31 raises the difficulty that this passage has no connection with sacrifice or the offering of blood, and it may represent a later addition, at least as it stands in 1 Corinthians. In Luke, the statement that the blood is shed “for you” (Luke 22:20) would suggest an already existing liturgical use. In favor of the version in Matthew and Mark, it can be argued that covenant, blood (sacrifice), and meal are already connected in Exodus 24:8, to which it alludes (see also Deuteronomy 12:7). Why should this stark version of the words of institution as found in Matthew and Mark not be the authentic one, precisely because it is more difficult to understand and accept in a Jewish context? In an original way, the words of Jesus link the expectation of the Messiah with the suffering servant of Isaiah 53, who lays down his life “for many.”

Origin Story

To conclude, then, there is no compelling reason not to accept the origin of the words of institution in Jesus himself. The Apostle Paul, who is usually regarded as the earliest witness to the Last Supper tradition (circa 53/54), claims to pass on what he has received from the Lord himself (1 Corinthians 11:23). The fact that he and Luke include the command “Do this in remembrance of me” (1 Corinthians 11:25; Luke 22:19) would imply a liturgical practice that was already observed in Christian communities.

The next entry in this series will look at the early Christian understanding of the Eucharist and the development of its liturgical form.

Notes:

- Josef A. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia), trans. Francis A. Brunner, 2 vol. (New York: Benziger, 1951–1955), vol. I, 7. ↑

See Paul Bradshaw, Reconstructing Early Christian Worship (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2009). 3-19. ↑

See, above all, Brant Pitre, Jesus and the Last Supper (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015); also Craig Blomberg, Contagious Holiness: Jesus’ Meals with Sinners (Downer’s Grove: Inter Varsity Press, 2005); Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2017). ↑

See, for example, Eugene LaVerdiere, Dining in the Kingdom of God: The Origin of the Eucharist according to Luke (Chicago: Liturgical Training Publications, 1994). ↑

- See Joseph Ratzinger–Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth. Part Two: Holy Week. From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection, trans. Philip J. Whitmore (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2011), 112-115; John R. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. Volume One: The Roots of the Problem and the Person, The Anchor Bible Reference Library (New York: Doubleday, 1991), 398-399. ↑

The five “primary criteria” listed by Meier are: (1) embarrassment (the difficult idea of eating the flesh and drinking the blood of Christ; see John 6); (2) discontinuity (the originality of Jesus’ “new Passover”); (3) multiple attestation (as seen); (4) coherence (with the mission of Jesus and in particular with his Passion); (5) Jesus’ rejection and execution (the alienation caused by the difficulty and novelty of the words). See Meier, A Marginal Jew, vol. I, 168-177. ↑