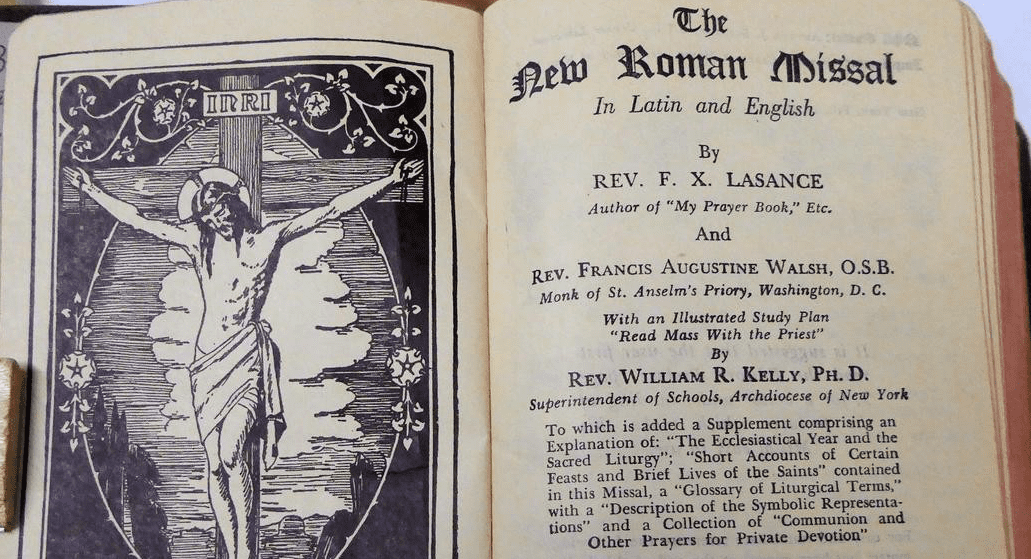

“It’s the ‘Cadillac’ of all hand missals,” my friend told me, as we rode the bus in the early hours of a cold Sunday morning in Milwaukee. This was my first foray into the “Latin Mass,” and I wasn’t sure what to expect. Yet, I had a sense of the beauty of the Latin and I was glad to have the trusty Father Lasance New Roman Missal to help me understand what lay behind the veil of the melodious Latin chant I would hear. Ever since that Sunday, I’ve always had a love for hand missals—helping to enter more deeply into the Mass, prayerfully meditating on the words and uniting myself to Christ’s sacrifice as Christ makes the Church manifest at each Mass.

All this is why these words from Dom Prosper Guéranger’s opening volume of The Liturgical Year puzzled me: “In order to conform with the wishes of the Holy See, we do not give, in any of the volumes of our Liturgical Year, the literal translation of the Ordinary and Canon of the Mass; and have in its place endeavored to give, to such of the laity as do not understand Latin, the means of uniting, in the closest possible manner, with everything that the priest says and does at the altar.”[1]

What on earth was this about? Wasn’t it a good thing to have translations of the Mass texts in the hands of the laity so they can unite with “everything that the priest says and does at the altar”? How did it come about that the Holy See restricted literal translations of the Ordinary and the Canon of the Mass, as Abbot Guéranger indicates? And why today is there not only an English translation provided in the missal for the Mass of 1962 (the Extraordinary Form) but the Mass in the ordinary form is almost exclusively celebrated around the world in the vernacular? For a solution to these puzzles, it is important to piece together some Church history.

Vernacular History

It was in the face of the Protestant Reformation that the council fathers at Trent did not think the liturgy itself “should be celebrated in the vernacular indiscriminately” (DH 1749). Indeed, in the canons that followed the above statement in the decrees, the fathers of Trent went on to anathematize those Protestant Reformers who condemned the rubric of praying “part of the canon and the words of consecration…in a low voice” (DH 1759).

Luther himself was certainly in view here: “Would to God that [the priest] would shout [the words of institution] loudly so that all could hear them clearly, and, moreover, in the German language.”[2] For Luther, the words of institution, or Verba Solemni, are essentially proclamatory and should therefore “be heard by everyone in the attending congregation, so he calls for these words to be sung.”[3]

Following upon Luther, the seventeenth-century Jansenist movement asserted that just “as the Bible ought to be intelligible to all, so too should the liturgy. The Jansenists wished to supplement careful instruction with at least a partial translation” [4] and called for the use of “vernacular missals at Mass.”[5]

It is significant to note here that while the fathers at Trent did not think it opportune to celebrate the liturgy “in the vernacular indiscriminately” (DH 1749), they did not utterly condemn the practice in principle. Rather, Trent recognized that so many of the Protestant Reformers asserted the illegitimate nature of celebrating the Sacraments in Latin.

Speaking from Within

In the context of Trent and the centuries that followed, the insistence on the vernacular was most prominently tied to sentiments that were either anti-Papal or which denied Catholic teaching on the Sacraments and the Mass in particular. But in 1660, it was a wholly Catholic undertaking that made the first attempt within the Church to publish a vernacular form of the Mass. The Director of the Sorbonne, Joseph Voisin, “published a five-volume translation of the Missel romain, the text in Latin and French, with notes and commentary in French alone.”[6]

Though authorized by the vicars-general of Paris, the work was immediately condemned by the “the Assembly of the Clergy, the Sorbonne, and the Royal Council.”[7] Indeed, Pope Alexander VII “joined in with an astonishing brief of 12 January 1661, not only censuring the ‘son of perdition’ who had made the translation, but also ‘rejecting, condemning and interdicting all translations that may be made of the book of the mass.’”[8]

Another attempt to vernacularize the Mass came with the rise of Jansenism, a Catholic theological movement that soon became tainted with a neo-Protestant outlook, including a Calvinist view of man’s inherent depravity and an undue emphasis on predestination. Although Jansenism is most closely associated with its French proponents, the movement found its full flowering in the Italian region of Tuscany and, “chiefly owing to the anti-Papal policy of the Grand Duke Leopold, Jansenism became so strong [in this region] that the local Synod of Pistoia (1786) promulgated one of the most comprehensive statements of Jansenist positions that exist,”[9] advocating among other things for “a vernacular liturgy, and the government of the Church by synods and national councils.”[10] Nevertheless, even where this pseudo-Protestant or anti-Catholic sentiment was lacking, opportunities for the use of the vernacular were slowly adopted.

A Clear Mission

Some opportunities for the use of the vernacular in relation to the liturgy opened up in mission lands. In 1615 the mission to China brought forth the permission of Pope Paul V “to celebrate mass in Chinese.”[11] Indeed, in “1631, full vernacular privileges were granted to missionaries in Georgia for the celebration of Mass in either Georgian or Armenian. On the other side of the Atlantic in the region around modern-day Montreal, Jesuit missionaries received permission from the Holy See for use of the Iroquois language in the liturgy. At the first Diocesan Synod of Baltimore held in November 1791, Bishop John Carroll (d.1815), allowed some use of English within liturgical celebrations: the Gospel was to be read in the vernacular on Sundays and feast days, followed by a sermon in English, and vernacular hymns and prayers were recommended, as well. In 1822, Bishop John England of Charleston, South Carolina, edited the first American edition of the Roman Missal in English.”[12]

Thus, Trent’s recognition that the “Mass contains much instruction for the faithful” and her concern that “the children beg for food but no one gives to them” (DH 1749), gained greater weight in mission lands, even as use of the vernacular in Europe remained contested. But even in Europe, the Church was warming to the idea of the vernacular in liturgy. Particularly effective were the arguments of Archbishop Colbert of Rouen, “who taught in a pastoral that the ancient mode of celebrating Mass in the language of the people was the fittest means to prepare the minds of the congregation for participation in the sacrifice.”[13]

Colbert’s arguments were defended by Pope Benedict XIV, who “in 1757 authorized vernacular translations” of the Bible, “provided they were approved at Rome and contained explanations by orthodox scholars.”[14] However, with the advent of the Jansenist Synod of Pistoia (1786) and the French Revolution (1789), a more cautious approach to the vernacular in relation to the liturgy came to the fore. Indeed, as “late as 1851 and again in 1857, the Holy See refused to allow liturgical translations in the vernacular, even as a tool for the laity in greater appreciation of the Mass.

Rite of Passage

All of that changed exactly twenty years later when, in 1877, the same Pope Pius IX (1846–78) who forbade vernacular translations, completely reversed his decision, allowing any bishop to authorize a translation and the use of vernacular missals by the laity.[15]

Pope Leo XIII followed this by “silently [omitting] the ban on translation of the mass into the vernacular” with the 1897 “edition of the Index of Prohibited Books.”[16] In this way, Leo XIII allowed hand missals to be published “on the ordinary imprimatur basis according to the judgment of each bishop.”[17] It is at this point that we can see a slow movement toward the proliferation of hand missals containing a translation of the Mass into the vernacular, including the Canon and Dominical words of the Mass.

As many in the Liturgical Movement pushed toward the use of the vernacular in relation to the liturgy, some insisted on not merely the use of vernacular missals, but “use of the vernacular” even “in the celebration of the august eucharistic sacrifice” (Mediator Dei, 59). However, since the situation confronted by Trent had changed and “since no Catholic would now deny a sacred rite celebrated in Latin to be legitimate and efficacious,”[18] a way was opened for the Second Vatican Council to decree that “since the use of the mother tongue [i.e., the vernacular], whether in the Mass, the administration of the sacraments, or other parts of the liturgy, frequently may be of great advantage to the people, the limits of its employment may be extended. This will apply in the first place to the readings and directives, and to some of the prayers and chants, according to the regulations on this matter to be laid down separately in subsequent chapters” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 36).

Several years later—on the eve of the move to the vernacular in the Novus Ordo—Pope Paul VI complemented the sentiments previously quoted from Dom Guéranger (above). Paul said, the understanding “of prayer is worth more than the silken garments in which it is royally dressed. Participation by the people is worth more.”[19]

Vernacular Solus?

Having taken a cursory look at how the ban on vernacular translations of the Mass came about—and then evaporated—we are brought back to our original query: why was there a ban on vernacular translations of the Ordinary and Canon of the Mass? In the face of much post-Reformation catechesis and apologetics with regard to the nature of the Eucharist, why not have vernacular translations of the basic texts of the Mass?

After our current experience of fifty uninterrupted years of vernacular usage, let me speculate that perhaps this reticence to give a literal translation of the Ordinary and the Canon was rooted in the good of both guarding and revealing the mystery. In 1978 and again in 1999, Joseph Ratzinger, “to the annoyance of many liturgists,” argued “that in no sense does the whole Canon always have to be said out loud.”

In contradistinction to Luther’s assertions above, Ratzinger writes, “It is no accident that in Jerusalem, from a very early time, parts of the Canon were prayed in silence and that in the West the silent Canon—overlaid in part with meditative singing—became the norm. To dismiss all this as the result of misunderstandings is just too easy. It really is not true that reciting the whole Eucharistic Prayer out loud and without interruptions is a prerequisite for the participation of everyone in this central act of the Mass.”[20]

Indeed, Paul VI remarks—in the very same address on the eve of the implementation of the Novus Ordo—“the silences” in the Novus Ordo “will mark various deeper moments in the rite.”[21] Ratzinger concludes this plea for silent participation in the Canon by an appeal to experience that goes beyond words:

“Anyone who has experienced a church united in the silent praying of the Canon will know what a really filled silence is. It is at once a loud and penetrating cry to God and a Spirit-filled act of prayer. Here everyone does pray the Canon together, albeit in a bond with the special task of the priestly ministry. Here everyone is united, laid hold of by Christ, and led by the Holy Spirit into that common prayer to the Father which is the true sacrifice—the love that reconciles and unites God and the world.”[22]

While I continue to appreciate the gift of that “Cadillac” of hand missals on that cold Sunday morning in Milwaukee all those years ago, I can all the more appreciate the gift and task of language and its limited ability to unite us to the mysteries celebrated in the liturgy. Perhaps what was being fought for in limiting literal translations of the Canon and the words of institution into the vernacular was a deep reverence and awe for the mystery that lies beneath the words. But such a topic is itself perhaps best left in silence to be taken up for another occasion.

[1] Dom Prosper Guéranger, The Liturgical Year, Tr. L. Shepherd (Dublin: James Duffy & Sons, 1870), 13.

[2] Martin Luther, “Sermon on the Worthy Reception of the Sacrament, 1521,” in Luther’s Works, Vol. 42: Devotional Writings I, ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 42 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 173.

[3] Robin A. Leaver, Luther’s Liturgical Music: Principles and Implications, ed. Paul Rorem, Lutheran Quarterly Books (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2007), 180.

[4] John McManners, Church and Society in Eighteenth-Century France: The Religion of the People and the Politics of Religion, ed. Henry Chadwick and Owen Chadwick, vol. 2, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press Inc., 1998), 429.

[5] James Hitchcock, History of the Catholic Church: From the Apostolic Age to the Third Millennium (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2012), 333.

[6] John McManners, Church and Society in Eighteenth-Century France: The Religion of the People and the Politics of Religion, ed. Henry Chadwick and Owen Chadwick, vol. 2, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press Inc., 1998), 45.

[7] John McManners, Church and Society in Eighteenth-Century France: The Religion of the People and the Politics of Religion, ed. Henry Chadwick and Owen Chadwick, vol. 2, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press Inc., 1998), 45.

[8] John McManners, Church and Society in Eighteenth-Century France: The Religion of the People and the Politics of Religion, ed. Henry Chadwick and Owen Chadwick, vol. 2, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press Inc., 1998), 45.

[9] F. L. Cross and Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 867.

[10] John McManners, Church and Society in Eighteenth-Century France: The Religion of the People and the Politics of Religion, ed. Henry Chadwick and Owen Chadwick, vol. 2, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press Inc., 1998), 665.

[11] Adrian Hastings, The Church in Africa, 1450–1950, ed. Henry Chadwick and Owen Chadwick, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press Inc., 1994), 112.

[12] Keith F. Pecklers, Liturgy: The Illustrated History (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press; Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2012), 168.

[13] William E. Addis and Thomas Arnold, A Catholic Dictionary (New York: The Catholic Publication Society Co., 1887), 502.

[14] John McManners, Church and Society in Eighteenth-Century France: The Religion of the People and the Politics of Religion, ed. Henry Chadwick and Owen Chadwick, vol. 2, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press Inc., 1998), 200.

[15] Keith F. Pecklers, Liturgy: The Illustrated History (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press; Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2012), 168.

[16] Owen Chadwick, A History of the Popes, 1830–1914, ed. Henry Chadwick and Owen Chadwick, Oxford History of the Christian Church (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 361.

[17] Keith F. Pecklers, Liturgy: The Illustrated History (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press; Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2012), 168.

[18] The Roman Missal: Renewed by Decree of the Most Holy Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, Promulgated by Authority of Pope Paul VI and Revised at the Direction of Pope John Paul II, Third Typical Edition. (Washington D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 22: GIRM §12.

[19] “Address of Pope Paul VI to a General Assembly, November 26, 1969,” in James Likoudis and Kenneth D. Whitehead, The Pope, the Council, and the Mass: Answers to Questions the “Traditionalists” Have Asked, Revised Edition. (Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road Publishing, 2006), 337–338.

[20] Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. John Saward (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 215.

[21] “Address of Pope Paul VI to a General Assembly, November 26, 1969,” in James Likoudis and Kenneth D. Whitehead, The Pope, the Council, and the Mass: Answers to Questions the “Traditionalists” Have Asked, Revised Edition. (Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road Publishing, 2006), 338.

[22] Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. John Saward (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 215–216.