At the dawn of the early modern era (15th century), an enterprising scholar may have boldly but not implausibly claimed to have read every book ever printed in a chosen theological field. The succeeding centuries have, for good or ill, witnessed such an accretion of academic output as to place that sort of comprehensive knowledge well beyond the imagination—let alone the reach—of most researchers. Specialization, periodization, and the decline of Latin learning have all contributed to the fragmentation of academic discourse, and even those who have attained a certain mastery of a field during graduate studies may find it difficult to stay abreast of developments if they leave the university setting for pastoral ministry.

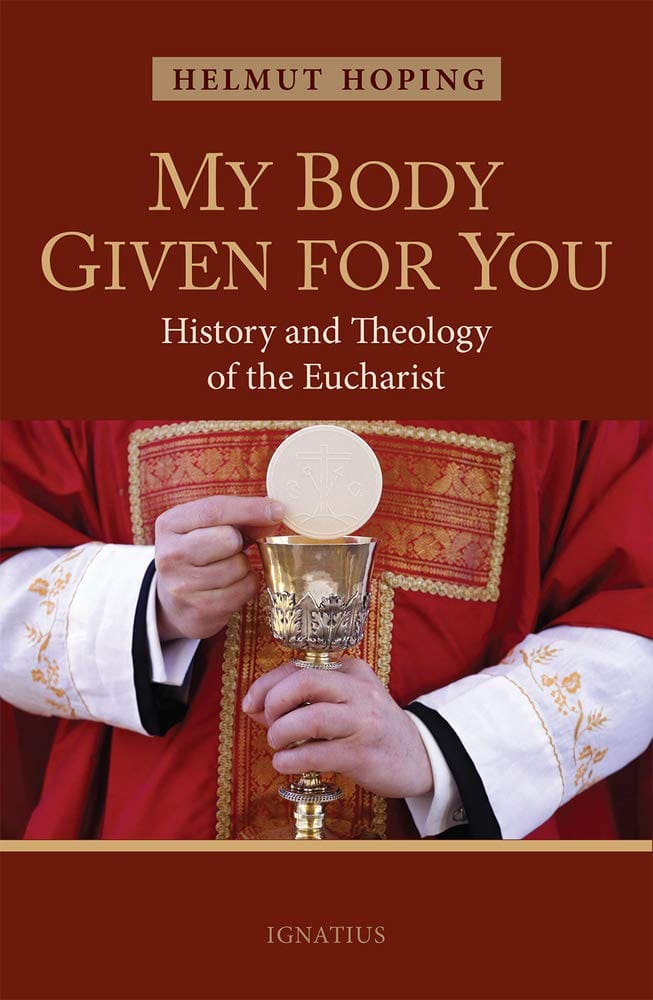

No single resource can alleviate all of these difficulties, yet, by providing an English edition of a recent scholarly work in German, Ignatius Press and translator Michael J. Miller have offered readers a useful status quaestionis for various lines of inquiry surrounding liturgical history, theology, and praxis. In this second, expanded edition of My Body Given for You: History and Theology of the Eucharist (Ignatius Press, 2019), Helmut Hoping, professor of theology at the University of Freiburg, proceeds from the standpoint that “the meaning and the liturgical form of the Eucharist cannot be separated [from each other] any more than liturgy and dogma or pastoral practice and doctrine can.” Since “faith and worship belong together inseparably,” this book represents an attempt to bring together in one place “the systematic theological approach to the Eucharist of dogmatic theology with the perspective of liturgical studies” (13).

Hoping’s introductory chapter provides a concise overture of theological themes that are interwoven throughout the coming historical considerations, most notably Karl Rahner’s challenge to develop a notion of sacrifice that does equal justice to both the history of religions and the New Testament accounts (16–17). The theology of gift to which he gestures at this point not only returns in the ultimate chapter to synthesize the book’s content, but it also informs Hoping’s historical analyses of both theological developments and shifts in liturgical practice across the centuries. His interest in those practical shifts is not in the ritual developments, per se, but in their implications for the unfolding of the Church’s faith. The liturgy, after all, is both the event wherein the Church experiences “as nowhere else the presence of Christ and of the salvation founded upon Him” (20) as well as the primary supposition of the Church’s theological reflection (24).

Christ’s Eucharistic Presence

Upon what, then, does Hoping choose to reflect? Many points within the development of the Roman Rite of Mass and its liturgical books receive brief mention in this broad 2000-year survey: whether the Didache relates a Eucharist or agape, monetization of Mass offerings, the introduction of the post-consecration elevations, and the ban on translations of the Roman Canon. Since it would be impossible to relate them all, it may be better to trace just one theme that receives sustained treatment across several historical periods: the proper understanding of Christ’s presence in the Eucharistic species. A spectrum of theologies on the manner of Christ’s presence in the Blessed Sacrament appears through sketches of patristic sources, but Hoping does not settle into systematic investigation until the Eucharistic controversy sparked between Paschasius Radbertus (c. 790–c. 860) and Ratramnus (d. 868) during the Carolingian period. The focused attention on this controversy is likely driven by the opportunity to mark philosophical shifts—from Neo-Platonism to Aristotelianism, and from a unified conception of image and reality to a conceptual framework that divorces the two (176–177)—that present marked difficulty for modern readers of early Christian texts. But one suspects that the fair-minded Hoping is also intrigued by the messiness of controversies whose victors, if you will, still fell somewhat short of the Church’s ultimate mark.

When Berengar (c. 1010–88) picked up Ratramnus’ non-realist conception of the Eucharistic species, multiple means to correct his teaching were employed. While the second oath imposed upon Berengar was designed to correct the dangerously exaggerated realism of the first (e.g., that the Eucharistic Body of Christ is “ground by the teeth of the faithful”), certain theological paradigms proffered by Berengar would prove to stand the test of time, including his brief definition of a sacrament as a “visible form of invisible grace” (197). Hoping does not, to be clear, suggest that these doctrinal determinations are entirely understood. Still, in relating the history he allows all thinkers to speak for themselves and is confident enough to point out error without the need to pile on in condemnation.

This historical chronicle of straining toward a better understanding of the manner of Christ’s presence in the Eucharistic species carries through the Reformation controversies. There the Reformers’ positions contradicted, in one way or another, the patristic views on Eucharistic Presence. Nevertheless, Catholic proposals also struggled to articulate a Real Presence that left room for Christ as principal celebrant of the Eucharistic sacrifice (248). Amid all this, Luther, though mistaken in rejecting transubstantiation, still held a sufficiently robust doctrine of Presence that remaining differences between transubstantiation and consubstantiation converge significantly in modern ecumenical discourse (395). Hoping’s generosity of interpretation extends also to modern Catholic attempts to replace transubstantiation with non-Aristotelian concepts such as transfinalization or transignification—these focused on the meaning of the Christ’s presence in the sensible elements rather than on describing the change that happens in the elements themselves. Paul VI did not condemn these theories outright; he merely asserted their insufficiency (see Paul VI, Mysterium Fidei, 11, 46). Thus, while explanations through a new end (“transfinalization”) or sign value (“transignifiation”) cannot replace transubstantiation, they can still enrich our understanding of the concept (427).

In support of this portrayal, Hoping cites Ratzinger’s view that, through conversion into Christ’s Body and Blood, the Eucharistic elements cease to be “things” with their own creaturely independence and “become pure signs of his presence” (427). This is hardly the first time Hoping resorts to Ratzingerian explanations to reconcile modern scholarship with more traditional articulations of the faith. Hoping’s openness to the best in all views bears such affinity to Ratzinger’s thought that it comes as no surprise to learn that Hoping, albeit only recently, has become a corresponding member of the Pope Emeritus’ “new Schülerkreis,” or distinguished alumni. The dynamic orthodoxy favored by this school has not, at least in Hoping’s case, settled into a stale outlook whose opinions can easily be predicted. In fact, when addressing another major topic of this book, liturgical reform, Hoping proves just as willing as Ratzinger to adopt an independent line.

Liturgical Reform

“The reform of the Mass no doubt produced numerous good fruits, for example:” vernacular liturgy, the expanded cycle of readings, obligatory homilies, the Prayer of the Faithful, more Prefaces, the new Eucharistic Prayers, Communion of the faithful within Mass and under both species, and renewal of the ministries of lector and cantor (312). With such a list of perceived improvements, Hoping is clearly a supporter rather than detractor of today’s liturgy. Yet this support does not preclude an honest assessment that, with so many changes made to a Mass refined over multiple centuries, “there are doubts as to whether they complied with the principle of organic development of the liturgy. From the long perspective, a balance between preservation and renewal is not always discernible” (ibid.). Some reconciliation between the eventual reform and the Second Vatican Council’s original intentions is thus in order.

Hoping understands Sacrosanctum Concilium to have called not for a reformatio of the Church’s liturgy but for an instauratio, a renewal to bring the liturgy more clearly in line with already existing principles and precedents (286). He also signals agreement with Joseph Gelineau (1920-2008) and Joseph Ratzinger that what happened instead was a complete replacement of the Roman Rite; the historical form was “demolished” (as Ratzinger put it) and a new one constructed. Siding with Ratzinger, now against Gelineau, Hoping makes this observation with no marked enthusiasm for the destruction, despite retaining his appreciation for the continuity and good fruit that remain. While reading Summorum Pontificum’s unity of the two rites as a primarily legal instrument with more aspirational than objective import, he remains fully convinced that “anyone who participates in Holy Mass in grateful adoration can tell that there is no contradiction between the old form and the new form […]. For as much as there is a need for a ‘reform of the reform,’ it is nevertheless clear also that the liturgy cannot be frozen in the state in which it existed in 1962” (364).

By indicating that Benedict XVI, who certainly celebrated the modern rite in continuity with the past, initiated no concrete reform project beyond liturgical translations, Hoping simultaneously signals his understanding of the reform of the reform as requiring future textual or structural changes. Yet those who share his hope for such changes will be disappointed to see that his review of established scholarship does not venture further into modern lines of inquiry or even test his own assertions in the same comprehensive manner as earlier questions. For instance, Hoping concludes that the Roman Mass likely never included an Old Testament reading as a regular feature (137). He also stresses that the catechetical dimension of the liturgy must never be elevated above its primary end of latria, or worship (290). Why then, not engage—even if only to disarm—modern concerns that the simultaneous adjustments in the quantity, selection, language, minister, and location of the scriptural readings have combined to obscure their latreutic character? If the Roman Canon likely never contained an epiclesis (148), why should the new Eucharistic Prayers, which Hoping welcomes, all have been constructed on a non-Roman epicletic model? Given ongoing debates about the methods and ministers of Holy Communion, why does the medieval withdrawal of the chalice from lay communicants receive no more than a passing mention in a single sentence? Surely this had greater theological repercussions than that single sentence acknowledges, regardless of whether one supports the current method of receiving the Precious Blood.

This is not to say that Hoping leaves reform of the reform perspectives entirely untouched. On the contrary, he defends the de jure post-conciliar presumption of ad orientem worship (355–358). It does mean, however, that the erstwhile revisionist (and now mainstream) lines he rightly adopts (against synagogal origins for the Liturgy of the Word [83], or for the Apostolic Tradition’s Syrian origins [123]), are responses to debates of the past rather than contributions to present-day reforms. And this is perfectly adequate to Hoping’s project, which if polemical at all is not designed to litigate the details of ritual reform but to carry forward the conciliar theology of liturgy as the priestly prayer of the whole Christ, Head and members. Medieval thought, he contends, failed to maintain an “awareness that the offering of the faithful and the Church’s prayer of thanksgiving are central” to the Mass (170). The past century, in contrast, has rightly seen both elements return to prominence.

A Eucharistic Theology of Gift

Thus, in ending with a phenomenological account of the Eucharist as “gift of life,” “gift of presence,” and “gift of transformation,” Hoping steers his reader away from previous over-clericalized or transactional concepts of the Eucharistic sacrifice and toward an understanding that is selfless on all sides. Jesus, in dying for mankind, was not a “victim” of violence but a sacrifice offered of his own accord (418)—not as an act of destruction, but of total self-surrender to God (414). The true form of the Eucharist is an offering-in-thanksgiving for this selfless act. As God has given himself as a free and unmerited gift for all of humanity, so the baptized offer themselves with the Eucharistic elements as gifts from God and returning to him. In carrying out his liturgy among us, the Son transforms our bodily existence into a living sacrifice (419–421).

Though one might wish Hoping had said more about various subjects within his survey, one cannot accuse him of losing his way within that forest of liturgical detail. This guiding perspective of liturgy as self-offering unites his sections and scholarly opinions and provides valuable food for thought for all those who seek to advance the liturgical apostolate.