A Centenary of Romano Guardini’s Spirit of the Liturgy, Part VII

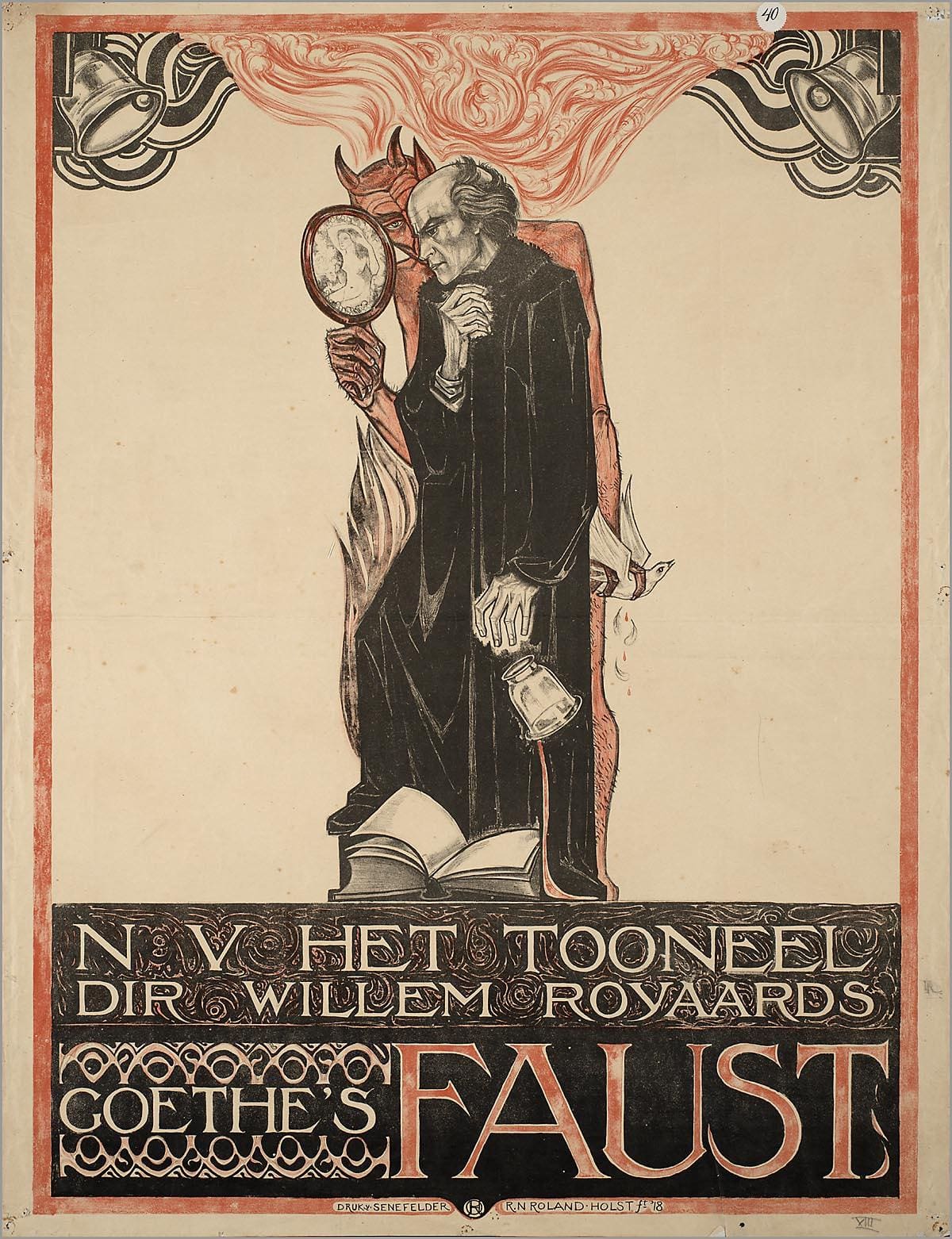

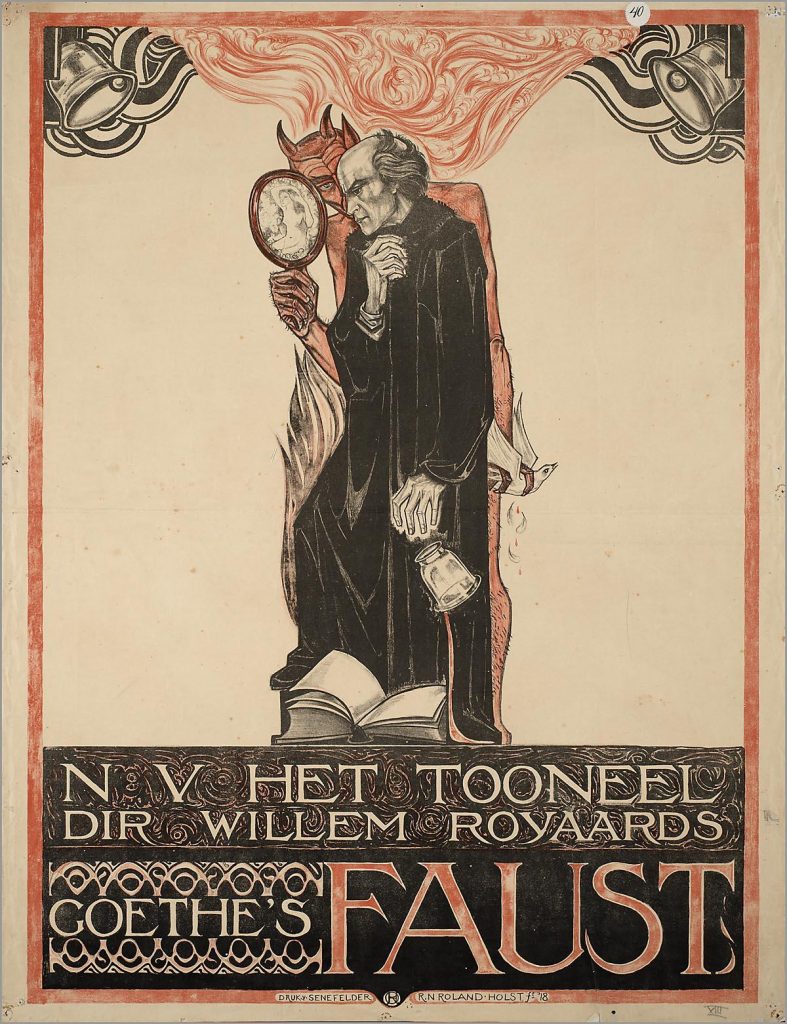

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God…. And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only-begotten Son from the Father” (John 1:1,14). In the concluding chapter of The Spirit of Liturgy, Romano Guardini thrusts the reader into the dilemma of the highly learned scholar Faust in the quintessentially German play Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832): does the Word or the Deed enjoy pride of place? That is, which is more fundamental in the Christian life: knowledge and truth (Logos) or will and action (Ethos)? After pondering this question, Faust, in the manner of a usurper and revolutionary, “corrects” the prologue to John’s gospel and writes “not ‘In the beginning was the Word,’ but ‘In the beginning was the Deed.’”[1]

The Spirit of the Liturgy was first published in 1918, republished 25 times in German, and is now available in not less than ten languages. Today the book continues to challenge us to offer a Christian response to Faust.[2]

To understand how the liturgy provides such a response, guiding the will according to truth, it is important to visit the Faustian tension that Guardini draws our attention to in this final chapter—“The Primacy of the Logos over the Ethos,” that is, the Word over the Deed. In order to understand this distinction, in turn, we take a helpful trip back to Germany with a man who would be pope.

German Interlude

After his years as provincial of the Argentinian Jesuits, Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio (b.1936) came to Germany to earn a doctorate in sacred theology (STD) at the Jesuit philosophical-theological college of St. Georgen, Frankfurt am Main, under the direction of Father Michael Sievernich, S.J. The topic should have been “Polar opposition as Structure of Daily Thought and Christian Proclamation”—also on the primacy of Logos over Ethos, inspired by the title of the final chapter of Guardini’s classic and by Father Sievernich’s philosophical text Der Gegensatz (The Opposition).[3] It seems Pope Francis joins other thinkers like Guardini in opposing Hegelian dialectics (where a resolution replaces two opposites) in favor of a Catholic “maintaining tensions”—as it was put succinctly by Blessed John Henry Newman (1801-90). Both Francis and Newman favor reconciling theological tension in a way that does not resolve friction in favor of one pole or eliminate polarities altogether. In this final chapter of his The Spirit of the Liturgy, Guardini holds the following positions:

- It is only with the eyes of God, from the perspective of the Blessed Trinity, that everything in this world receives its proper valence and dignity.

- Created in the image of God, but in a postlapsarian state, the human person must continually make the ethical effort to behold the world as divinely willed; and therefore

- The Christian is obligated to not only resist, but also combat, all forms of self-enamored immanentism (i.e., God’s exclusive abiding in the world).

This final accord as it applies to questions of the liturgy is translated in the book’s last chapter head as “The Primacy of Logos over Ethos.” Like Guardini, Bergoglio the doctoral candidate seems to perceive an underlying tension between these two key terms. Unfortunately, Bergoglio’s doctoral project never materialized. On the occasion of The Spirit of the Liturgy’s centenary, though, it is fitting to reconsider Guardini’s closing argument. Not only may it shed some light on the thinking of Pope Francis, who also approaches matters of faith, and especially of the liturgy, with a tension-filled polarity of dialectics, but such a study will also illuminate the essence—the spirit—of the liturgy, our principal goal.

Come Together

In Guardini’s writings every word is carefully weighed and considered and graced with a special timbre. This renders his writings inimitable and thus irreplaceable. He commonly refrains from arguing against another thinker, but rather—in the manner of true classic authors—intends to distill what is abidingly relevant and prevailing despite the vicissitudes of history.

Guardini begins the chapter by registering the regret many express for Catholic liturgy’s apparent unrelatedness to current affairs and practical matters of daily life. (When using the term “liturgy,” Guardini consistently means the Eucharist, the Catholic Holy Mass.) Indeed, he emphasizes, liturgy resists being translated into action. These well-intended critiques are the occasion for him to develop the danger of allowing “outcomes” to determine the nature and purpose of liturgy. While not dwelling on the eminently doxological nature of the human person and the cosmos, he reminds his readers that “liturgy…is primarily occupied in forming the fundamental Christian temper.”[4] He does not deny that worship impacts the moral order. However, this is a necessary secondary consequence, not its purpose.

To establish the proper frame of reference for the tension between Logos and Ethos, Guardini points out that in the Christian Middle Ages primacy was given to the Logos vis-à-vis Ethos. The human will and its attendant activities were perceived during the Middle Ages as formed by and, therefore, the natural outgrowths of the Logos. Not only does the Logos chronologically precede all human activities, it also ontologically undergirds human action—and liturgical action. Provocatively, the “truth is truth because it is truth,”[5] irrespective of what the will may interject, and therefore serves as the basis for Ethos. To this end, Guardini sees the rich devotional lives of Catholics, such as praying the rosary, meditations, processions, etc. as felicitous appropriations and incorporations of the Logos into the concrete and personal lives of the faithful. (Guardini would pen precious meditations on the Stations of the Cross in 1921.)[6]

Holding Logos as the foundation for Ethos granted medieval society a historically unparalleled and singular cohesion and solidarity, enabling it to be more than a pragmatic commonwealth, but one of a shared meaning and thus shared destiny. The foundational Logos spelled out the nature of Gemeinschaft (community) versus merely Gesellschaft (society), and was expressed in a lasting manner in works of art. For instance, this position found visible expression in Italy’s medieval municipal Signorias (city halls) adorned with saints and making no distinction between sacred and secular realms, just as today, of course, this shared meaning becomes ever again present in the liturgy: the Eucharist as the Thou of God in Jesus Christ—divinity appearing in the common accidents of bread and wine. (Guardini further develops this dimension on a broad canvas in The Lord years later.)[7]

We’re Breaking Up

But following the Middle Ages, as the positive sciences ascended from the Renaissance onward, “the fulcrum of the spiritual life gradually shifts from knowledge [of the Divine] to the [human being’s subjectively formed] will,”[8] now perceived as autonomous and at best defined exclusively by verifiable, empirical criteria. As a result of this shifting emphasis from Logos to Ethos, from truth to action, our age is “a powerful, restlessly productive, laboring community.”[9] Modernity has lost sight of a vital component of existence: listening to and obeying the inner order of being. “Contemplation of God or love of Him”[10] is no longer deemed foundational to minds formed in primarily practical matters. Guardini thinks here not only of the large, dehumanizing factories, such as those found in the grand modern metropolises of Berlin, Paris, or London, that result in massified individuals. He is also thinking of the ideas that generated these inhuman work centers, especially those of Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Will to Power.[11] Guardini considered the work puerile, if not pathological and benighted—although today, tellingly, it is much read by the Western intelligentsia. Guardini asserts already for this age and time that “the Ethos has obtained the primacy over the Logos.”[12]

Will and Kant

But we need to take a step even further back in the history of German philosophy to understand how this usurpation of the primacy given to Logos by Ethos was prepared decades earlier than Nietzsche by German philosopher Immanuel Kant. His philosophy of epistemological reticence (i.e., elevating human willing over knowing) is the logical conclusion of Lutheran 16th century anthropology, which grants human nature per se nothing positive in the order of salvation. For Luther and Kant were in agreement that truth can no longer be perceived as of value apart from criteria distilled wholly from the immanent order. For Luther and Kant, too, faith thus becomes the child of the will, and no longer resting on knowledge of truth. After all, Kant sees dogma as incapable of informing what human nature is. Indeed, for Kant, dogma is a superstitious position that must gradually retreat into the dustbins of history as human reason irresistibly expands our horizon of possible knowledge. Then, invariably we come to worship success. Yet, the content of success is defined independently from the Creator. Such is the “New World.” “The practical will is everywhere the decisive factor,” Guardini writes, “and the Ethos has complete precedence over the Logos, the active side of life over the contemplative.”[13] Even liturgy in the modern world becomes a practical, results-based activity.

Catholicism’s position in this regard must be always diametrically opposed to such a worldview, as the Church is the vessel containing divine revelation, thus illuminating to man both his and the world’s purpose. To this end, Guardini calls for a return to a Christ-centered understanding of reality—a Logos-centered view—one which can only benefit the liturgy and souls encountering Christ in the liturgy. Indeed, the Second Vatican Council spells out Guardini’s Christocentrism with a celebrated line in Gaudium et Spes 22: “In reality it is only in the mystery of the Word made flesh that the mystery of man truly becomes clear.” Were the Council Fathers then mindful of Guardini’s observations? If they weren’t, it was at least clear that Guardini expresses and even anticipates the conciliar mind of the Church on this matter.

As stated, Guardini sees Protestantism as catalyst and representative of the posture that prioritizes Ethos over Logos. This posture stands in stark relief to the Church’s more inclusive view of Logos and Ethos as a tension held, especially in the liturgy, in proper order. Guardini’s contemporary Adolf von Harnack (1851-1930), the premier Protestant theologian of the day, had drafted Kaiser Wilhelm II’s declaration of war in 1914. Did this bring into prominent focus for Guardini the foundational weakness of Protestant theology? Guardini sees Kant rightly “called [Protestant theology’s] philosopher.” Guardini writes that the Kantian spirit “has step by step abandoned objective religious truth, and has increasingly tended to make conviction a matter of personal judgment, feeling and experience. …The relation with the supertemporal and eternal order is thereby broken.”[14]

Consequently, in the Kantian and Lutheran line of thought, scripture, dogmatizations, and liturgy are not inspired products of salvation history flowing from the decisive moment of Christ’s death and resurrection and giving expression to eternal truth; rather, these elements in the life of faith are entirely immanent events, subject to revision. Here the Faustian temptation to make the Deed the first word of salvation becomes a frightening realty.

Bargaining Souls

But even World War I was only a prelude to the twentieth-century fascination with this temptation. Hardly twenty years after the end of this first war to end all wars, the Ethos became all-dominant during the ugly works and days of the Nazi Third Reich. In reaction to this ugliness, the world heralded a 1960 German film version of Goethe’s Faust. The critics reserved special praise for the German actor Gustav Gründgens’s stellar performance of Mephisto, the demon tempter and beguiling protagonist who urges Faust (and, the German audience might say, Hitler) to embrace the primacy of Ethos. Shortly after the film was released, however, Gründgens died—possibly by suicide. The irony would not have been lost on either Goethe or Guardini: the human being is utterly unable to live a life “unrestrained” by the Logos.[15]

Guardini argues positively that the rejection of the Catholic, magisterial claim to the primacy of Logos leads to “the position of a blind person groping his way in the dark, because the fundamental force upon which it has based life—the will—is [now] blind. The will can function and produce, but cannot see. From this is derived the restlessness which nowhere finds tranquility.”[16] As we will see, this restlessness finds rest in a will guided through prayer in the liturgy.

This situation is also intensified in postmodernity, wherein the individual constantly and breathlessly performs and consumes and knows of no home. He seeks in temporality a transcendental meaning, which must remain elusive, but for this reason postmodernity offers incentives to invent more consumer goods. Both performance and free time are placed under the dictatorship of the Ethos. Leisure, a cousin of the liturgy, becomes a frightful perspective that needs to be avoided at all costs, lest one need confront the truth of being, the Logos. In the ductus of Guardini’s The Spirit of Liturgy, Josef Pieper (1904-97) writes Leisure, the Basis for Culture (1948)[17] and Hugo Rahner (1900-68) pens Man at Play (1952).[18] Do both Pieper and Hugo Rahner feel inspired especially by this last chapter of The Spirit of Liturgy? Human contemplation is but a retracing of a truth contained in things, which is a cognitive retracing of God’s thoughts.

Life in a Word

Logos, the Word, is apprehended as one constantly effected by God and not a merely impersonal process. The things in this world bear its meaning and message. The primacy of the Logos allows for spontaneity both on God’s side and on our side. Influenced by Bonaventure and with numerous fellow thinkers, Guardini shares skepticism as regards rigid systems and theoretic presentations. But Guardini is doing nothing more than the Church has always done. Catholicism has always resisted the temptation to reduce metaphysics, truth, and dogma to ethical conceptions and to be guided by moral or pragmatic considerations divorced from a grounding in the divine. Cultic worship is similarly far more than education of the individual to be a good citizen à la the Enlightenment. We may become better citizens for going to Mass, but that’s not the primary purpose of the divine liturgy. In this context Guardini reminds the reader that even God as the Blessed Trinity, far from being impersonal or cerebral, is never merely an absolute will “but, at the same time, truth and goodness.”[19] In this way, the Trinity is also the perfect model for the liturgy. The triune God is a constant living out of personal relationships of mutual commitment in love.

With Augustine, Guardini understands this charity as the Holy Spirit. Thus, the Blessed Trinity is perceived as the template for human beings and society. Is this “Augustinian interiority” what Pope Francis intended to demonstrate in his dissertation project? A community grounded in the incarnate God formed for Guardini the basis for the anti-Nazi activists Hans and Sophie Scholl’s sacrifice of life in 1943. Guardini honors the witness of this community when he writes that it “lived in the radiance of Christ’s sacrifice…issuing forth from the creative origin of eternal love.”[20] The incarnate Logos, Jesus Christ, is the enabler of human charity and participation in divine vivacity. And even as this divine love was a harmonizing principle of word and act for the Scholls, so too it will always be in the case, and more so, in the Catholic liturgy.

Word and Deed

The epochal process of depersonalization that the 21st century countenances may be seen as the consequence of giving Ethos priority over and against Logos. But it would be incorrect to assume action is of inferior value to that contemplation. It is the Logos that dignifies action, i.e., transforms all action into Ethos beyond compare.

Therefore, Logos and Ethos are not two entities that must be inexorably cancelled out in an immanent process for a higher third to emerge (à la Hegel’s dialectical understanding of history). Neither can the claim be made that knowledge is more important than life. Rather, Guardini writes, “[i]t is partly a question of disposition; the tone of man’s life will accentuate either knowledge or action; and the one type of disposition is worth as much as the other…; in life as a whole, precedence does not belong to action, but to existence. What ultimately matters is not activity, but development”[21]—a reflected and deliberate growth towards eternity, a growth that is at once human and informed by the divine life of grace.

At this point the question arises: what kind of thing is Logos? Does “truth insist upon love or upon frigid majesty?” Guardini asks.[22] Ethos on its own subjugates us to an impersonal, Kantian “obligation of the law” as defined by Kant’s The Postulates of Practical Reason; but Guardini responds that Logos evokes “the obligation of creative love.”[23] But this is not a complete answer to the question either. Rather, with the Johannine Christ he argues the “good tidings”[24] announce nothing less than that love is the greatest. The personal truth of the Thou of God “shall make you free” (John 8: 32) from the burden to justify human existence via tangible, human criteria. Jesus Christ shines forth not as the final arbiter between Logos and Ethos, but as that singular reality that provides the proper equilibrium between the two, an equilibrium fully displayed in the harmony of the Logos and Ethos of the liturgy.

“In dogma, the fact of absolute truth, inflexible and eternal, entirely independent of a basis of practicality,” Guardini writes, “we possess something which is inexpressibly great. When the soul becomes aware of it, it is overcome by a sensation as of having touched the mystic guarantee of universal sanity; it perceives dogma as the guardian of all existence, actually and really the rock upon which the universe rests. ‘In the beginning was the Word’—the Logos….”[25] In this way, Guardini responds to Goethe’s Mephisto and suggests a restoration of the balance that the modern has lost.

Because that “guarantee of universal sanity” is so necessary for human existence, Guardini considers contemplation indispensable to genuine freedom. There is the call for the human being to ponder eternity to comprehend the eternal nature of his soul. “It is peaceful,” Guardini writes, “it has that interior restraint which is a victory over life” for the sake of life.[26] For this reason the Catholic faith, he notes, cannot “join in the furious pursuit of the unchained will, torn from its fixed and eternal order.”[27]

Rather, the personal Logos, Jesus Christ, establishes a harmony that does not eliminate Ethos but provides its sure grounding in the order of being. “In the liturgy the Logos has been assigned its fitting precedence over the will,” Guardini states. In the accompanying footnote he adds: “Because it reposes upon existence, upon the essential, and even upon existence in love….”[28] Human existence’s purpose is contemplation, adoration, and glorification of divine truth. “The liturgy has something in itself reminiscent of the stars, of their eternally fixed and even course, of their inflexible order, of their profound silence, and of the infinite space in which they are poised.”[29]In The Spirit of the Liturgy, Guardini thankfully provides a map to these stars, poised between the word and the deed, the Logos and the Ethos.

[1] Romano Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy. Readings in Liturgical Renewal, trans. by Ada Lane, foreword by Joanne M. Pierce (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2004); first English edition 1930, p. 90.

[2] Romano Guardini, Vom Geist der Liturgie (Mainz, Ostfildern: Grünewald/Schöningh, 2013), pp. 89f.

[3] www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article114452124/Bergoglio-studierte-einst-in-Frankfurt-am-Main.html accessed 10.12.2017. Romano Guardini, Der Gegensatz. Versuche zu einer Philosophie des lebendig Konkreten (Mainz: Matthias Grünewald, 1991), originally 1955.

[4] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 86.

[5] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 91.

[6] Romano Guardini, Der Kreuzweg unsres Herrn und Heilandes, (Matthias Grünewald: Mainz, 1921).

[7] Romano Guardini, The Lord (Washington, DC: Regnery, 2002) orginally published in 1937.

[8] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 87.

[9] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 87.

[10] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 86, footnote 2.

[11] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, volumes I and II, an attempted Transvaluation of all Values (Boston, MA: Digireads, 2010) originally published posthumously 1901.

[12] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 88.

[13] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 89.

[14] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 90.

[15] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 90.

[16] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 91.

[17] Josef Pieper, Leisure: the Basis of Culture (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2009).

[18] Hugo Rahner, Man at Play (New York: Herder and Herder, 1972).

[19] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 91, footnote 5.

[20] Romano Guardini, Die Waage des Daseins (Tübingen/Stuttgart: Wunderlich, 1946) p. 18: “obedience vis-à-vis the interior call.”

[21] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 92.

[22] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 93.

[23] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 93.

[24] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 93.

[25] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, pp. 93f.

[26] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 94.

[27] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 94.

[28] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 94 and footnote 9. Emphasis added.

[29] Guardini, The Spirit of Liturgy, p. 95.