Reprinted from Adoremus Bulletin, September 2011

“Why was there a need for the reform of the liturgy? Can you summarize it for me? Some say that the Council intended a radical break with the past to make the liturgy relevant; others claim that the Council’s reform of the liturgy was the nefarious work of a few people determined to destroy the Church!”

This question, from a serious and well-informed Catholic, is representative of many similar questions we’ve encountered recently. It is a different question from “why do we need a new translation”—though it is not entirely unrelated to this significant change in the language of worship we are about to encounter.

More likely, such questions arise in the context of the recent change that permits the old form (vetus ordo) of the Mass to be celebrated side-by-side with the new (novus ordo). People who never experienced the pre-conciliar liturgy, and who have only known a wholly vernacular Mass that may vary widely from parish to parish—and especially those who are attracted to the solemnity and reverence characteristic of the “extraordinary form” of the Mass—are curious about why there ever should have been a liturgical reform. If Pope Benedict, in issuing Summorum Pontificum in 2007, intended to permit wider use of the “extraordinary form” alongside the “ordinary form,” doesn’t this suggest that the liturgical reform was not needed?

We, too, have read the extreme views of the liturgical reform that the letter-writer mentions. Though they reach polar opposite conclusions, both views have in common one basic assumption: that the Council’s liturgical reforms represent a rupture, or “discontinuity” with the entire history of the Catholic Church’s liturgy—and both views are equally and very seriously mistaken, as Pope Benedict has stressed repeatedly. The liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council are, truly, in continuity with the Church’s history. And a liturgical reform was needed—and still is.

Here’s an attempt to pack an eventful century into a very short space.

The Pre-conciliar Liturgical Reform

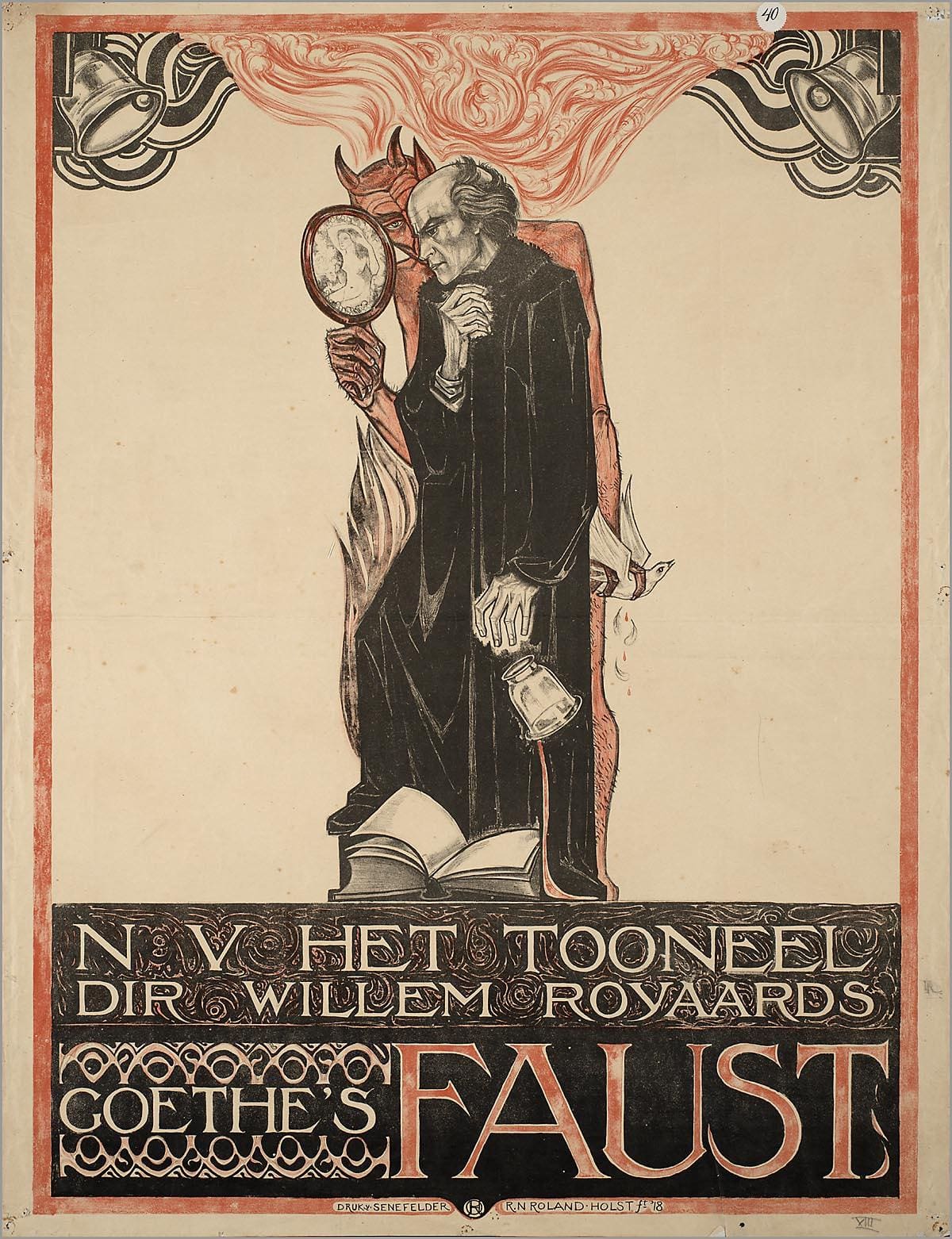

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pope Pius X initiated what would become known as the “liturgical movement” with his 1903 document on sacred music, “Tra le sollecitudini.” Building on an initiative that had begun in the early 19th century to recover the Church’s nearly lost patrimony of Gregorian Chant, and responding to the dominance of theatrical-style music performed at Mass, which left the congregation as a passive audience, the pope called for a restoration of sacredness to music—and for the “active participation” (actuosa participatio) of the entire congregation in the holy sacrifice of the Mass.

The “liturgical movement” had many variations in Europe and America; but the principles that Pope Pius X first expressed were repeated by subsequent popes. Pope Pius XI’s 1929 encyclical on the Liturgy and music, Divini Cultus, also underscored the importance of truly sacred music in worship.

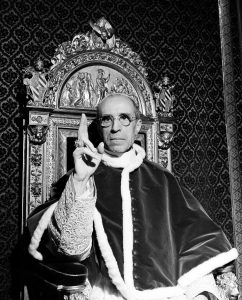

In the 1950s, Pope Pius XII reformed the celebration of Holy Week—and new vernacular translations of the Bible were undertaken. The pope issued key encyclicals on the liturgy: Mediator Dei (1947) and Musicae Sacrae (1955), in which he reaffirmed the active participation of the people, the members of the Mystical Body of Christ, and approved recent historical research, while he also cautioned against errors and innovations advocated by some liturgical reformers that were inconsistent with the Church’s liturgical heritage and tradition.

During the decade or so before the Second Vatican Council the “dialogue Mass” appeared, in which the congregation made the appropriate responses in Latin—formerly made only by the altar boys—although this did not become standard practice.

Ordinary Mass-goers were encouraged to follow the Mass in bilingual hand missals in order that they could more fully understand what was taking place in the sanctuary, even though they could not actually hear the priest’s words. But the use of hand missals, too, was the exception rather than the norm.

At the time of the Council, the liturgical movement had made some progress in the effort to increase the understanding of ordinary Catholics and to draw every Catholic believer more closely into the sacred action of the Mass—the “source and summit” of the Catholic faith—and thereby to become more deeply and spiritually connected to the heart of the Church, the Mass.

However, this goal still remained distant. The usual parish Mass was still almost entirely inaudible to the worshippers (except for the sermon), impossible to follow (except for the bell at the consecration), and the congregation mostly knelt silently and said the Rosary or other prayers during the entire celebration of Mass, except when they actually received Holy Communion.

At the same time, some of those who were actively involved in the liturgical movement were veering perilously from the Church’s liturgical tradition, often in pursuit of their own interpretation of the liturgies of the “early Church.” Liturgical mistakes were made, as Pope Pius XII had observed and censured in Mediator Dei.

The Second Vatican Council’s Reform

Recognizing the fundamental importance of the Mass in every Catholic believer’s life—a goal of the pre-conciliar liturgical movement that had remained elusive—the fathers of the Second Vatican Council made their first work the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium (1963).

The Constitution reaffirmed the central and indispensable role of the liturgy in Catholic life, and in this document the Council fathers called for a liturgical reform—stressing again the active participation of the laity, precisely in order that the liturgy would become the center of every faithful Catholic’s life. This was the true objective of the liturgical reform, as it had been for many years.

The Constitution’s directives were by no means extreme, and essentially reaffirmed the earlier papal documents on the liturgy. While they authorized more use of the vernacular in the liturgy, along with Latin, the Council fathers could not and did not foresee the rapid disappearance of all Latin from the Mass; nor could they ever have imagined the radical departure from the Church’s traditional liturgical practice that would take place with alarming and confusing speed during the 1960s and 1970s.

A New Liturgical Movement

The Council’s reform was genuinely needed. But the errors resulting from misinterpretation of the Council were very serious, indeed, and these errors led to divisions within the Church.

Correction was clearly necessary. Thus Pope John Paul II called for a new reform of the liturgy in Vicesimus Quintus Annus, his letter on the 25th anniversary of the Council’s Constitution on the Liturgy. The letter describes both the positive and negative effects of the post-conciliar liturgical renewal, and concludes:

“The time has come to renew that spirit which inspired the Church at the moment when the Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium was prepared, discussed, voted upon and promulgated, and when the first steps were taken to apply it” (§23).

Pope John Paul thus set in motion a plan to get the liturgy back on course—a new liturgical reform.

The phrase “new liturgical movement” was used by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger in his 1997 memoir, Milestones. Here is the relevant section, in which we can hear echoes of the criticisms by earlier popes of the failures of the liturgical reform to achieve its real purpose:

“There is no doubt that this new Missal [after Vatican II] in many respects brought with it a real improvement and enrichment; but setting it as a new construction over against what had grown historically, forbidding the results of this historical growth, thereby makes the liturgy appear to be no longer a living development but the product of erudite work and juridical authority; this has caused us enormous harm. For then the impression had to emerge that liturgy is something ‘made’, not something given in advance but something lying within our own power of decision. From this it also follows that we are not to recognize the scholars and the central authority alone as decision makers, but that in the end each and every ‘community’ must provide itself with its own liturgy. When liturgy is self-made, however, then it can no longer give us what its proper gift should be: the encounter with the mystery that is not our own product but rather our origin and the source of our life. A renewal of liturgical awareness, a liturgical reconciliation that again recognizes the unity of the history of the liturgy and that understands Vatican II, not as a breach, but as a stage of development: these things are urgently needed for the life of the Church. [Emphasis added.]

“I am convinced that the crisis in the Church that we are experiencing today is to a large extent due to the disintegration of the liturgy, which at times has even come to be conceived of etsi Deus non daretur [Lit., as if God is not given], in that it is a matter of indifference whether or not God exists and whether or not He speaks to us and hears us. But when the community of faith, the worldwide unity of the Church and her history, and the mystery of the living Christ are no longer visible in the liturgy, where else, then, is the Church to become visible in her spiritual essence? Then the community is celebrating only itself, an activity that is utterly fruitless. And because the ecclesial community cannot have its origin from itself but emerges as a unity only from the Lord, through faith, such circumstances will inexorably result in a disintegration into sectarian parties of all kinds—partisan opposition within a Church tearing herself apart.

“This is why we need a new Liturgical Movement, which will call to life the real heritage of the Second Vatican Council” [Emphasis added] (Milestones – Memoirs 1927-1977 (1997, English edition, 1998, Ignatius Press, p 148-149).

Rupture or Reform and Renewal?

Pope Benedict XVI, in his now-famous address to the Roman Curia on December 22, 2005, forty years after the Second Vatican Council ended, reflected on the way the Council had been received and interpreted. “What has been the result of the Council?” the new pope asked. “Was it well received? What, in the acceptance of the Council, was good and what was inadequate or mistaken?… Why has the implementation of the Council, in large parts of the Church, thus far been so difficult?”

The answer, he explains, lies in the correct interpretation and application of the Council—“on its proper hermeneutics.”

“On the one hand,’ Benedict says, “there is an interpretation that I would call ‘a hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture;’ it has frequently availed itself of the sympathies of the mass media, and also one trend of modern theology. On the other, there is the ‘hermeneutic of reform,’ of renewal in the continuity of the one subject-Church which the Lord has given to us. She is a subject which increases in time and develops, yet always remaining the same, the one subject of the journeying People of God.

“The hermeneutic of discontinuity risks ending in a split between the pre-conciliar Church and the post-conciliar Church. It asserts that the texts of the Council as such do not yet express the true spirit of the Council. It claims that they are the result of compromises in which, to reach unanimity, it was found necessary to keep and reconfirm many old things that are now pointless.… In a word: it would be necessary not to follow the texts of the Council but its spirit.”

But this shows a basic misunderstanding of the very nature of a Council, he says. “The hermeneutic of discontinuity is countered by the hermeneutic of reform…. It is precisely in this combination of continuity and discontinuity at different levels that the very nature of true reform consists.”

Pope Benedict again recalls the serious problem of the “hermeneutic of discontinuity” in interpreting the Council in Sacramentum Caritatis, his apostolic exhortation following the Synod on the Eucharist (February 22, 2007). He also emphasized that the “riches” of the liturgical renewal “are yet to be fully explored”:

“The difficulties and even the occasional abuses which were noted, it was affirmed, cannot overshadow the benefits and the validity of the liturgical renewal, whose riches are yet to be fully explored. Concretely, the changes which the Council called for need to be understood within the overall unity of the historical development of the rite itself, without the introduction of artificial discontinuities” (§3 [Emphasis added]).

This authentic liturgical reform—overcoming “discontinuities” and “ruptures” in the Church’s history, and renewing and restoring the “spiritual essence” of the Mass, the heart and font of our faith—is what we are now experiencing, more than 100 years after Pope Pius X’s initial actions, and nearly half a century after the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Liturgy.