What hath Humanae Vitae to do with the Liturgy? On the surface, they are further apart than Athens and Jerusalem. Yet, both Humanae Vitae and the liturgy are about the transmission of life—human life and divine life. God has placed the transmission of human life in the context of matrimony, which is a divine sacrament “not only when it is being conferred,” but perdures “for as long as the married parties are alive.”[1] So Humanae Vitae speaks not only to the transmission of human life, but to the spiritual fruitfulness of the Sacrament of Holy Matrimony.

What hath Humanae Vitae to do with the Liturgy? On the surface, they are further apart than Athens and Jerusalem. Yet, both Humanae Vitae and the liturgy are about the transmission of life—human life and divine life. God has placed the transmission of human life in the context of matrimony, which is a divine sacrament “not only when it is being conferred,” but perdures “for as long as the married parties are alive.”[1] So Humanae Vitae speaks not only to the transmission of human life, but to the spiritual fruitfulness of the Sacrament of Holy Matrimony.

Frustration Temptation

Contraception can be understood as “every action which, either in anticipation of the conjugal act, or in its accomplishment, or in the development of its natural consequences, proposes, whether as an end or as a means, to render procreation impossible.”[2] When the man and the woman speak the words of consent in the marriage liturgy, they begin a marriage contract and so form a covenant which establishes “between themselves a partnership of the whole of life…which is ordered by its nature to the good of the spouses and the procreation and education of offspring” (CIC 1055 §1). Indeed, the establishing of the marital covenant is not only a liturgical action, but one that culminates in a bodily consummation that renders the bond, established in the liturgical action, indissoluble. Pope St. John Paul II articulates what the Biblical witness testifies to, asserting that “without this consummation [of the wedding vows in the marital act], marriage is not yet constituted in its full reality.”[3] This is to say that sexual union is that action by which the covenant liturgy of marriage is itself fully realized.[4] In this way, the sacrament of matrimony has an especially unique tie to the actions that follow its ritual celebration.

This statement should call to mind Biblical texts where sexual union itself seems to make marriage. For example, Deuteronomy 21:13 “deals with the captive woman’s right to mourn the loss of her family before being taken by an Israelite soldier. After her month of mourning, the text reads: ‘you may go in to her, and therefore be her husband, and she shall be your wife.’”[5] Some have argued that, in the Biblical witness, “the act of sexual union by itself is constitutive of marriage.”[6] Yet, even in these cases, consent must either be supplied later or given prior to consummation. In the case of Jacob and Leah, “it is apparent that copula carnalis is not simply a characteristic feature of marriage; it is the decisive expression of the end of mere betrothal and, as such, consummates the marriage.”[7] Even when it is a question of premarital sex, all the Biblical examples “encourage or insist on the formalizing of marriage following” such an act.[8] Indeed, without the consummation of the marriage, the marriage contract is itself open to dissolution.[9] Summing up the Biblical witness, John Paul II writes, “the words themselves, ‘I take you as my wife/as my husband,’ do not only refer to a determinate reality, but they can only be fulfilled by the copula conjugale (conjugal intercourse).”[10] In this way, sexual union is understood to be the oath-sign of the covenant liturgy of marriage, fully realizing what is spoken in the consent. This “oath sign” embodies the words expressed by the man and the woman in the marriage liturgy.

Word and Deed

The terms of the covenant of marriage are expressed beautifully by The Order for the Celebration of Matrimony in the “Questions before Consent” where the priest or deacon puts the following questions to the man and the woman:

N. and N., have you come here to enter into Marriage without coercion, freely [libero] and wholeheartedly [pleno corde]?

Are you prepared, as you follow the path of Marriage, to love and honor each other for as long as you both shall live?

Are you prepared to accept children lovingly from God and to bring them up according to the law of Christ and his Church?

Since it is your intention to enter the covenant of Holy Matrimony, join your right hands and declare your consent before God and his Church.[11]

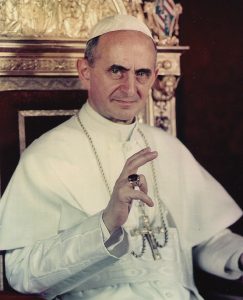

The terms of the marriage covenant laid out in these questions define the terms of the covenant of matrimony: if the couple answers in the affirmative to these questions, we know that it is their “intention to enter the covenant of Holy Matrimony.” Interestingly, although not surprisingly, these “Questions before Consent” in The Order of Celebrating Holy Matrimony closely parallel the characteristics of marriage described in Humanae Vitae. Blessed Pope Paul VI writes of the “characteristic features and exigencies of married love,” describing this married love as “an act of the free will [liberae voluntatis actu];” a “total [pleno]” gift of one person to another; a “faithful and exclusive [fidelis et exclusorius]” love that honors that reciprocal gift; and as a love that is “fecund [amor fecundus est]” in that it goes beyond mutual love between the spouses and embraces children as “the supreme gift of marriage” (§9).[12] These “characteristic features and exigencies of married love” are put to the man and the woman in the “Questions before Consent” in order to establish the couple’s “intention to enter the [one-flesh union] of Holy Matrimony” (OCM, §60–61).

What Genesis calls the “one flesh” union speaks words that God has impressed on our very being, and indeed our very bodies. Every time the marriage act takes place, man and woman—through the grammar of their bodies—communicate these words to each other: “I give myself to you freely, totally, faithfully, and fruitfully (cf. HV 9). I give you all of who I am and I receive all of who you are.” This free, total, faithful, and fruitful love is essential to being able to say, “I love you,” in the sense of “married love” (HV §9). Only if the act is free, total, faithful, and fruitful can a person give himself in love (cf. FC §37).

An “oath-sign” is the “act that seals or enacts the agreement.”[13] Every covenant has a ratifying action, so the covenant with Abraham in Genesis 17, for example, has circumcision. While Abraham and Sarah had gotten an heir by their own initiative in Genesis 16, circumcision was a concrete sign that in the context of a covenant relationship with the Lord, one “should not trust in flesh,” or his “own powers, in his own fertility to see God’s promise realized.”[14] As John S. Grabowski asserts, “if marriage is a covenant, then that covenant must have a sign, something that makes visible the invisible reality of this one-flesh union.… The sign of that unique covenant relationship is the physical act of becoming one flesh in sexual intercourse.”[15] So, sexual union is “the embodied gesture that expresses the new relationship which their covenant creates between them. Sex, therefore, as a recollection and enactment of the covenant oath takes on a liturgical function within the marriage relationship.”[16]

Past Presents Future

To speak of sex as a liturgical function within marriage implies that liturgical actions always include an invoking of the covenant for the sake of renewing it. As Ratzinger asserts, the “classical Old Testament liturgy…includes two aspects: the burnt offering and the reading from the book of the covenant.”[17] Indeed, the practice of renewing the Sinai covenant with the celebration of the Sabbath became the weekly occasion when the truth of what it meant to live in communion with God was made clear. Ratzinger writes:

“The Sabbath is introduced in the account of the creation as a time when man is made free for God. Beyond that, and in connection with the Ten Commandments, it is also a sign of God’s Covenant with his people. The original idea of the Sabbath is thus an anticipation of the freedom and equality of everyone. On the Sabbath, even a slave is not a slave; there is rest even for him.”[18]

Moving from weekly observance to daily observance, the Shema‘ Iśrāēl is the most pervasive of the daily actions of covenant renewal in ancient Judaism.[19] The recitation of the words from Deuteronomy 6:4–9 constituted “a daily renewal of commitment to God’s covenant with Israel,”[20] which was “linked directly to loyalty to law and covenant, to God’s kingdom.”[21] Indeed, this daily recitation at morning and evening has been called “the identity marker of covenant membership.”[22] The recitation of the Shema‘ Iśrāēl has been likened to the recitation of the Our Father, in that by praying these words Christians not only follow “the Savior’s command,” but are also “formed by [this] divine teaching”[23] on the nature of living in a covenant relationship with God.

However, as the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium states, for the Christian, it is fundamentally in the Mass where the “renewal in the Eucharist of the covenant between the Lord and man,”[24] takes place. So it is that “one of the primary functions of liturgy in biblical thought is to remember” the covenanting action “in a way that makes present the event commemorated.”[25] Indeed, to “remember [anamnesis] in the biblical sense is to act upon a covenant.”[26] The one-flesh union “is thus understood as a kind of anamnesis that recalls precisely the totality of a couple’s gift to one another expressed in their oath [taken during the marriage liturgy].”[27]

Publicly Discrete

Understanding the liturgy as the “public worship” of the “Mystical Body,”[28] one may question the application of the word “liturgy” in the sense being employed in the marriage act. Thus, we may call the consummation of the marriage vows a “public” action, akin to the public worship of the Church, in the sense that when the couple takes up a common domicile, they are publicly witnessing to a consummated marriage in their living out of the Sacrament of Matrimony.[29] And when they renew their marriage covenant in the one-flesh union, the act of marriage, they manifest the sacrament in a special way.

This notion fits with the Church’s teaching on the sacraments. In the language of sacramental theology, “through the action of Christ and the power of the Holy Spirit [the sacraments] make present efficaciously the grace that they signify” (CCC 1084). Since sexual “intercourse enacts in bodily form the unconditional promise and acceptance articulated by the couple in their wedding vows,” it is “genuinely sacramental” and liturgical in the sense previously asserted with regard to the liturgy: it completes and makes new the “consent that caused it.”[30] So, just as the Paschal Mystery, renewed in the Eucharist, is “the mystery of the spousal union between Christ and the Church,”By signifying the oath-sign in their enactment of the one-flesh union, the couple manifests the sacrament and opens itself to the renewal of the grace of the sacrament in their marriage.

Thus, the consent of the marriage liturgy continues to be spoken, but not so much in the verba solemnia of matrimonial consent, but in the language of the body. Because this language of the body is marital, and by its nature public, it approaches a true liturgical dimension as it renews the covenanting event of the couple’s marriage, which simultaneously draws its life and sacramentality from the Mystery of Christ’s union with his Bride. This liturgical dimension, Pope St. John Paul II asserts, “elevates the conjugal covenant of man and woman, which is based on the ‘language of the body’ reread in the truth, to the dimensions of the ‘mystery,’ and at the same time enables that covenant [of Christ and the Church] to be realized in these dimensions through the ‘language of the body.’”[32]

Thus, it is “from the words with which the man and the woman express their readiness to become ‘one flesh’ according to the eternal truth established in the mystery of creation, [that] we pass to the reality that corresponds to these words,”[33] the conjugal act.

Marital Bliss

In this way, when a married couple employs the use of contraception in the act of marriage, they commit a form of liturgical abuse. That is, the couple explicitly rejects the possibility of children by “deliberately” frustrating the marital act “in its natural power to generate life,”[34] the couple has altered its intent—no longer intending to carry out “the covenant of Holy Matrimony”[35] they previously entered, liturgically and otherwise, on their wedding day.

There is constantly a tension between the wedding vows, the life lived on a daily basis, and the consummation of those wedding vows in the act of marriage. If the free, total, faithful, and fruitful love that Blessed Pope Paul VI speaks about in Humanae Vitae (9) fails to correspond to the oath-sign of the conjugal act, then the oath-sign itself becomes a sign of contradiction. What Paul VI saw so clearly, that the gnostic tendencies of our culture often obscure, is the nuptial dimension of the body: sexual difference, love, gift, and fruitfulness cannot be uncoupled without effectively uncoupling the couple. Or, to quote Janet E. Smith, sex is about “babies and bonding” (Janet E. Smith, “Contraception: Why Not?”).

We are currently seeing that as the unitive and procreative have been pulled apart, the reality of sexual difference is being pulled apart as well. Nevertheless, as couples strive to let their married love correspond to the act of marriage, families flourish. Not simply in producing more offspring, but as life lived corresponds to conjugal love, the married couple becomes a more perfect sign in the world of Christ and the Church. In his study Domestic Church: Biblical and Theological Foundations of the Family, Joseph Atkinson illustrates how the family functioned as the carrier of the covenant in the Old Testament, and so it is today in the New Covenant Church. True conjugal love, grounded in Christ’s covenant with the bridal Church, is the source of the familial fruitfulness that caused the pagans in Tertullian’s day to say, “‘See…how they love one another.’”[36]

It may seem strange to speak of contraception as a form of liturgical abuse. After all, isn’t every instance of sin a sort of liturgical abuse? Do we not break our baptismal vows every time we give over our will to the world, the flesh, or the devil? Still, marriage has a unique place among the sacraments—for in its essence, it demands a post-ritual consummation.

Thus, while many might argue that contraception is a “private affair” between two consenting adults, the public reality of marriage is underscored by the public effects not only of flourishing married love, but also of contraception—such as increased frequency of divorce, infidelity, and domestic violence—leading to the continued dissolution of marriage in our day (cf. CCC 1606–1608). Therefore, given this predicament that modern marriage finds itself in, the liturgical aspects of marriage are worth examining, not only to remind the faithful of the public dimension of marriage, but also to recall why, for the sake of all men born of women, Christ deemed marriage important enough to raise to the level of a sacrament in the first place.

[1] Pius XI, Casti Connubii (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1930), §110, quoting St. Robert Bellarmine, De controversiis, tom. III, De Matr., controvers. II, cap. 6.

[2] Paul VI, Humanae Vitae (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1968), §14.

[3] John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body, trans. Michael Waldstein (Boston, MA: Pauline Books & Media, 2006), 532 (TOB 103.2).

[4] “Although Mary and Joseph were not two in one flesh, they were truly married, precisely in the sense that any bride and groom are married at the end of the wedding ceremony, when they have consented to marriage but not yet consummated it. The decision of Mary and Joseph not to consummate their marriage in no way violated the good of marriage. Moreover, even though their nonconsummated marriage never was “fully constituted as a marriage,” it was a true and ongoing covenantal communion, which was uniquely fulfilled: by the fruit of Mary’s womb, to whom Joseph, her husband, truly became father by consenting to God’s will for their marriage.” Germain Grisez, The Way of the Lord Jesus, Volume Two: Living a Christian Life (Quincy, IL: Franciscan Press, 1997), 587. See also Thomas Aquinas, STh., III q.29 a.2.

[5] S. Tamar Kamionkowski, “The Savage Made Civilized: An Examination of Ezekiel 16:8,” in “Every City Shall Be Forsaken”: Urbanism and Prophecy in Ancient Israel and the Near East, ed. Lester L. Grabbe and Robert D. Haak, vol. 330, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 130–131.

[6] Gordon P. Hugenberger, Marriage as Covenant: A Study of Biblical Law and Ethics Governing Marriage, Developed from the Perspective of Malachi (VTSup 52; Leiden: Brill, 1994), 279.

[7] Hugenberger, Marriage as Covenant, 251.

[8] ibid.

[9] See Hugenberger, Marriage as Covenant, 261–262.

[10] John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them, 532 (TOB 103.2).

[11] The Roman Ritual: The Order of Celebrating Matrimony, Second Typical Edition (Washington, D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2016), §60–61.

[12] Emphasis in the Latin text.

[13] Grabowski, Sex and Virtue, 31.

[14] Peter J. Leithart, Sacramental Theology, (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016), “Segment 4: Sacraments of the Law: Circumcision.”

[15] Michael Lawrence, “A Theology of Sex,” in Sex and the Supremacy of Christ (ed. John Piper and Justin Taylor; Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway, 2005), 137–38.

[16] Grabowski, Sex and Virtue, 38.

[17] Benedict XVI, Dogma and Preaching, 15–16.

[18] Joseph Ratzinger and Peter Seewald, God and the World: Believing and Living in Our Time: A Conversation with Peter Seewald, trans. Henry Taylor (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2002), 170–171.

[19] As Lawrence H. Schiffman notes, the recitation of the Shema‘Iśrāēl is alluded to in the Dead Sea Scrolls and is “the first topic of discussion in the Mishnah,” as well as being quoted by Jesus. Such usage confirms “the significance of the Shema in the Jewish practice of [Jesus’] time.” Katharine Doob Sakenfeld, ed. The New Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2006–2009), “Shema,” by Lawrence H. Schiffman.

[20] E. P. Sanders, Jesus and Judaism (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985), 141.

[21] N. T. Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2013), 180.

[22] Kim Huat Tan, “The Shema and Early Christianity,” Tyndale Bulletin 59, no. 2 (2008): 190–191.

[23] The Roman Missal: Renewed by Decree of the Most Holy Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, Promulgated by Authority of Pope Paul VI and Revised at the Direction of Pope John Paul II, Third Typical Edition. (Washington D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2011), 336.

[24] Second Vatican Council, “Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy: Sacrosanctum Concilium,” in Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and Post Conciliar Documents, ed. Austin Flannery (Northport, NY: Costello Publishing Company, 1992), no. 10.

[25] Grabowski, Sex and Virtue, 38.

[26] David W. Fagerberg, The Christian Meaning of Time: Feasts, Seasons and the History of Salvation (London: Catholic Truth Society, 2006), 59–60. It is particularly pertinent here to recall that the whole of the Eucharistic Prayer, particularly the anamnetic words, are spoken to the Father and are asking him to remember the covenantal actions of the Son.

[27] Grabowski, Sex and Virtue, 38.

[28] Pius XII, Mediator Dei (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1947), §20.

[29] “Though in some sense a very private act, as [a] liturgical [act] sexual intimacy also completes and signifies the relation of the couple as ‘one flesh’ and is an enactment and recollection of their public commitment within the community of faith.” John S. Grabowski, Sex and Virtue: An Introduction to Sexual Ethics, Catholic Moral Thought, Volume 2 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press), 45.

[30] Grabowski, Sex and Virtue, 46.

[31] Angelo Scola, “Marriage and the Family Between Anthropology and the Eucharist: Comments in View of the Extraordinary Assembly of the Synod of Bishops on the Family,” Communio 41, no. 2 (Summer 2014), 208–225, at 211.

[32] John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them, 613 (TOB 117b.2).

[33] John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them, 532 (TOB 103.3).

[34] Pius XI, Casti Connubii (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1930), §58.

[35] The Roman Ritual: The Order of Celebrating Matrimony, §61.

[36] Tertullian and Minucius Felix, Apologetical Works and Octavius, ed. Roy Joseph Deferrari, trans. Rudolph Arbesmann, Emily Joseph Daly, and Edwin A. Quain, vol. 10, The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1950), 99.