Daniel Mitsui is an artist on the move—although for a while it felt like he was stuck between things, a situation less than ideal for a Catholic artist who depends on the permanent and eternal to make his living.

Last May, when Mitsui spoke with Adoremus, his living room was full of moving boxes stacked against the wall. Apologetic for the clutter, Mitsui’s wife Michelle explained that they had never quite moved in because they were already preparing to move out. With their four children, the Mitsuis were renting a two-story house tucked behind downtown Des Plaines, IL. From this temporary in-between place, the Mitsuis were hoping to find more permanent digs outside Chicago’s suburbs.

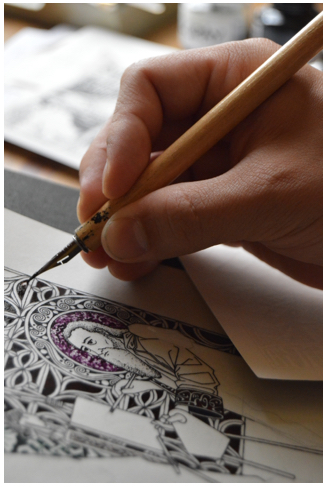

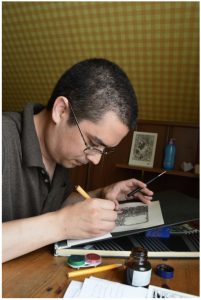

In the meantime, in his Des Plaines rental, Mitsui had established an ad-hoc garret-like studio, eked out of a spare attic room. Other than Mitsui’s drawing desk, the room held a few bookcases half-filled with reference books and a collection of cardboard boxes containing ink, paper, and other art supplies.

A Dartmouth College graduate and latecomer to the faith, Mitsui was baptized the year he graduated from the prestigious New Hampshire school, 2004. Today, at the ripe young age of 35, Mitsui is attempting to re-conquer the art world for the Catholic faith. A master of precision ink drawing, Mitsui’s output includes fine-lined pen-and-ink liturgical and devotional art and drawings that celebrate God’s creation. He executes a butterfly or a scarab beetle with the same style-defining passion for meticulous detail that many prize in his rendering of, say, the Crucifixion of Christ or a portrait of St. Patrick.

His artistic efforts have come also to the attention of the Vatican, which commissioned Mitsui in 2011 to illustrate a new version of the Roman Pontifical—the book of rites used by bishops. He also has a small collection of religious-themed coloring books published through Ave Maria Press, while his homegrown Millefleur Press also provides the public with a high-end publishing outlet—producing broadsides, bookplates and books that are, as his website notes, “works of art in their own right.”

Having developed his craft over the past 15 years, Mitsui—who originally hails from Georgia and was raised in Chicago—finds himself in transition, not only geographically, but also artistically, as he recently announced the launch of his most ambitious project to date: “Summa Pictoria: A Little Summary of the Old and New Testaments.”

As preparation for this project, each step in Mitsui’s artistic journey—beginning with his childhood fascination with art to his formal study of art as a young adult and his successful efforts as a Catholic artist today—has also brought Mitsui to a deeper faith in Christ. This love for God and his Church has allowed Mitsui in turn to remain faithful to his craft and take on a mission to harmonize the beauty of the artistic tradition and the tradition of artistic beauty for a world out of harmony with both.

Looking around the makeshift studio, Mitsui spoke about the need for more space—both for his art and for his family. Since that conversation in the temporary studio in Des Plaines, the Mitsuis have found a place in northwestern Indiana to call home and serve as headquarters for Mitsui’s artistic production company.

Past Sketches

While at Dartmouth, Mitsui received training in oil painting, charcoal drawing, animation, etching, lithography, and animation—although according to Mitsui it was his natural talent for precision handiwork that drew him to pen-and-ink as his chosen medium.

His mother’s love of books—she was a librarian—had influenced Mitsui’s love of art and research. “It was a bookish kind of household. There was a lot of reading in our family and certainly my penchant for drawing was encouraged.”

“Ink drawing was something I had done more of before college,” he says. “Then I tried these other media and that’s when I realized my particular skills are best applied in ink.”

While his parents were Christian and his mother raised Catholic, Mitsui did not have a strong formation in the faith by the time he reached college. “I had not been baptized as an infant and as a family we mostly attended Christmas and Easter Mass,” he says.

Something from those childhood Christmas and Easter liturgical excursions for the Mitsui family also must have had an effect, Mitsui says.

“Even though I didn’t have any real religious formation or catechism that endured, there was some exposure to the Mass—not regular but some exposure and I had the idea that the Catholic faith was the one true faith,” he says. “That experience of the liturgy also formed a connection in my mind between medieval art and the Catholic faith. Those were strongly associated which maybe wouldn’t have been if I had more of a typical parochial upbringing in the 1980s and 1990s.”

At age 14, Mitsui says, he also received valuable lessons in liturgical aesthetics by poring over illuminated manuscripts and by gazing at Gothic architecture at the University of Chicago.

“The first time I recall being in a Gothic structure, I was visiting the University of Chicago and visiting the chapels there,” he says. “I also remember having a fascination with certain churches surrounding the library where my mother worked—noting these towering spires and wondering what was inside them.”

Immediately apparent to the discerning eye, this love for all things Gothic carries over into Mitsui’s work.

“Gothic art is not as abstract as Coptic or Byzantine iconography, but neither does it present a natural and mundane view; the presence of haloes alone makes that obvious,” Mitsui notes in “Heavenly Outlook,” a lecture he delivered on Gothic art during an exhibition of his work this past August at St. John Cantius Church, Chicago. In Gothic art, Mitsui notes, “[t]here are no cast shadows. The size of figures is determined by their importance, their placement by the demands of symbolism, hierarchy, and symmetry.”

In Gothic art, Mitsui says, “[c]hronologically separate events are depicted together in the same scene. Nothing important is hidden behind another object, or cut off by the edges of the picture.”

While the innocence of wonder in Gothic forms inspired Mitsui to pursue an art career, he says that the unpleasant experience of the art world led him to turn his back on opportunities in the mainstream secular market. According to Mitsui, art should not be a pricey commodity for the few but an accessible patrimony for all—and he wants to reach as many people as he can to share that patrimony.

“I like to sell directly to people and price my art in such a way that I can attract patronage from ordinary people,” he says. “I like to see my work in homes and I don’t want to play the games where I get gallery representation, set my prices at an unbelievably high level, and expect to sell one or two pieces a year—if I’m lucky.”

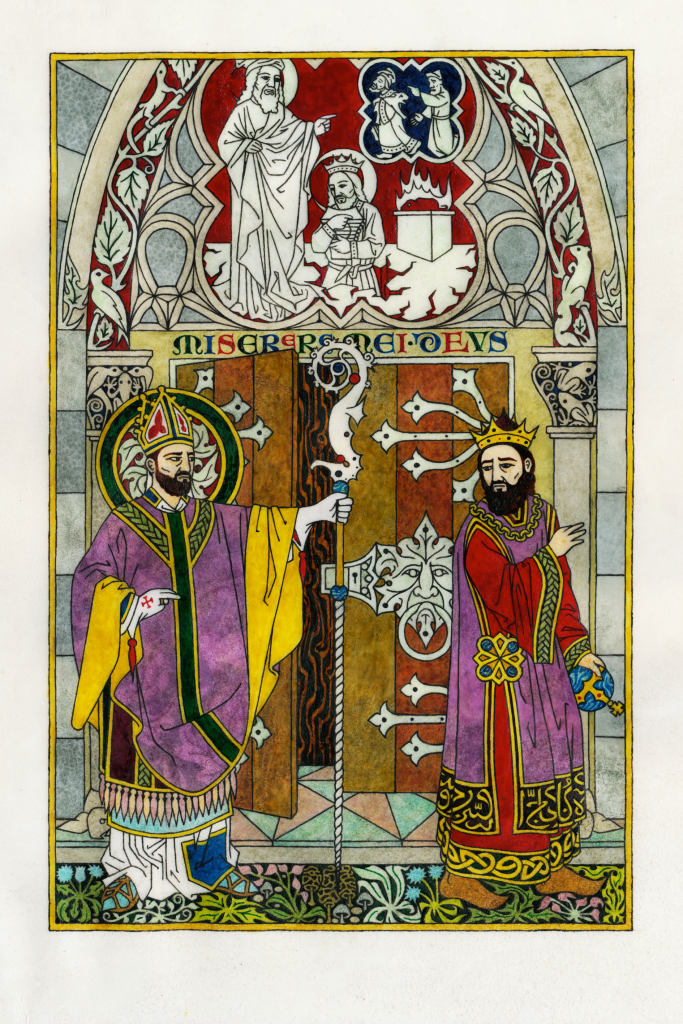

“The citizens of Thessalonica had aroused the Emperor’s wrath, but at Ambrose’s request he had pardoned them. Later the ruler, secretly influenced by some malicious courtiers, ordered the execution of a huge number of those he had pardoned. Ambrose knew nothing of this at the time, but when he learned what had happened, he refused to allow the Emperor to enter the church. Theodosius pointed out that David had committed adultery and homicide, and Ambrose responded: You followed David in wrongdoing, follow him in repentance. The most clement Emperor accepted the order gracefully and did not refuse to do public penance…. Being thus reconciled, he went into the church and stood inside the gates of the chancel. Ambrose asked him why he was waiting there. He said that he was waiting to take part in the sacred mysteries, to which Ambrose replied: O Emperor, the space inside the chancel is reserved for priests. Go outside therefore, and participate with the rest of the people. The purple makes emperors, not priests. The Emperor promptly obeyed.”

Says Mitsui: In depicting this event, I wanted to give emphasis to the ideas of repentance and forgiveness; in a quatrefoil above the door of the church, I drew King David confronted by the Prophet Nathan (whose parable appears in a smaller quatrefoil). The postures, clothing, and positions of these figures relate them to those of St. Ambrose and Theodosius below. The beginning of the psalm expressing King David’s repentance I wrote on the lintel. On the door is a sanctuary knocker (in the form of a green man, similar to that knocker on Durham Cathedral) which suggests again the idea of a church as a place for the repentant. Both St. Ambrose and the Emperor wear purple vestments; the color is a symbol both of repentance and of imperiality.

Rescuing the Sacred

Concerned that sacred images are being lost in the modern tendency to turn the venerable and sacred into kitsch, Mitsui uses a popular approach to art not to democratize it but to provide a sort of aesthetical evangelization of the world through sacred images. In “Invention and Exaltation,” a 2015 lecture at Franciscan University of Steubenville, OH, Mitsui says that sacred art must rise above the “superabundance of information” in which “holy images are not lost, but reduced to triviality.”

“Just about anyone in the world can download a high-quality digital photograph of the Chi-Rho page from the Lindisfarne Gospels, or the Incarnation Window at Chartres, or the Ghent Altarpiece,” he says in the 2015 lecture and exhibit. “He can print it to hang on his wall; or he can print it on a t-shirt, a coffee mug or the case of his smart phone. He can ‘like’ it on Facebook or ‘tweet’ it or ‘pin’ it without even taking a good close look at it. He can crop it and type the name of his ‘blog’ over it to make a cute title banner.”

In trivializing sacred art, Mitsui continues, modern culture has torn it away from its original purpose and meaning.

“At that point, religious art ceases to be about God and His angels and His saints,” he says. “It is not even about the artist who made it; it is about the person who chooses to like it. It is like a relic of the Holy Cross placed on a table to the right of a king’s throne: not destroyed, not forgotten, but not exalted either. It is set beside, rather than above, him.”

To accomplish this rescue mission, religious artists have two primary duties, Mitsui notes in his 2015 Franciscan lecture: invention and exaltation.

“Invention here has the older definition of the word; it does not mean creating from nothing, but rather finding,” he says. “If the artistic traditions have been buried, his task is to discover them; if they have been stolen, his task is to retake them. Once they are found or retaken, his task is to bring them to their proper place and give them honor as high as his abilities make possible; that is, to exalt them.”

Drawing from Liturgy

Mitsui’s desire to rescue and restore was inspired in large part by his own spiritual journey. In Mitsui’s junior year at Dartmouth he embraced the Catholic faith, received the sacraments of initiation and thereby sharpened the focus of his art.

“From that point,” he says, “I settled that I wanted to make religious art and go back to these medieval things that have always fascinated me.”

Referring to his first attempts at religious art as “bad convert art,” Mitsui found himself “overwhelmed by the history and possibilities.”

“I wanted to do everything,” he recalls, “and throw it together without order or discipline.”

To find this order and discipline, Mitsui would plumb the heart of the Church’s culture—the liturgy.

“It took a while to get a sense of the liturgical order in art,” he says, “and also of realizing how much the disciplined intellectual approach which went into Gothic art was what I wanted to use as a basis for my own art.”

Finding his faith through the liturgy, Mitsui continues to grow artistically through it as well, finding in it a veritable goldmine.

“When I go to Mass, I take note of how the various readings and chants correspond to each other,” he says. “Sometimes I notice something in a liturgical text which I realize I should give an expression to in artwork which I wouldn’t have seen otherwise.”

While Mitsui admits that most of his work is not ostensibly liturgical—“Some of it gets hung in churches or some of it goes into books that are used at the altar, but most of it is things people are going to be putting on their home shrines or used devotionally”—nonetheless, Mitsui finds the liturgical tradition foundational and indispensible to artistic composition.

“Whether art is used for private devotion or in a church itself, sacred art follows a tradition and principles that don’t come from the artist,” he says. “If art is sacred, it has to follow a tradition that is informed by the Church fathers, the liturgy and what was done in the past.”

Like all elements of liturgy, Mitsui says, his work should encourage the faithful to prayer even as it serves as an intimate part of prayer.

“Going back a while in history, there is this idea that to pray or worship means that you quietly think pious thoughts to yourself,” he says, “and anything artistic, any artistic form that makes it harder to think pious thoughts to yourself is a distraction and therefore not prayerful.”

But art must be a part of worship, Mitsui insists, and must participate in that same sacramental reality which turns earthly things grasped by the senses—water, bread, oil—into divine instruments of grace—baptism, communion, confirmation.

“The idea that worshiping would involve sacred art, architecture and music as part of the act of worship has become foreign to us,” he says. “But I’m trying to create images that have enough significant and symbolic detail that by looking at them for a longer time and concentrating on them, they become prayerful rather than being easy to ignore.”

“Your senses are a part of your Christian life as much as anything,” he adds. “I think that’s mostly forgotten these days.”

Tradition and the Individual Artist

Throughout history, the Church has always underscored the importance of the senses in worship, Mitsui says. For example, in 787 the Second Council of Nicea responded to the Byzantine Iconoclasm that followed from the imperial edict of Leo III and supported by the Council of Hieria (754), which called for the suppression of sacred images. At Nicea, the Church restored the use of icons as a means of devotion.

In his 2015 Franciscan University lecture, Mitsui notes that the Nicean fathers assert that “The Tradition does not belong to the painter; the art alone is his. True arrangement and disposition belong to the holy fathers.”

For Mitsui, artistry and tradition must work in harmony: “Artistry without tradition is like an empty reliquary; beautiful, perhaps, but unworthy of veneration. Tradition without artistry is like a relic kept in a cardboard box; worthy of veneration, but deserving of better treatment.”

By comparison, Mitsui says, religious art should not be confused with imaginative art.

“It’s as different as Adam of St. Victor writing a liturgical sequence for the Feast of St. Michael and a novelist writing a Catholic novel about St. Michael,” he says. “It’s a different approach, a different form of art and it has a different purpose.”

As a religious artist, Mitsui sees his efforts firmly planted within the tradition.

“I want to make things that have this liturgical, traditional, patristic order,” he says. “I want to be able to say that this work of art would be approved of by the council fathers who laid down these principles in the Council of Nicea.”

Taking the Second Council of Nicea as his north star, Mitsui refers to himself as “a Spirit of Nicea II Catholic.”

“That is a joke,” he says. “Its point being that I keep that ecumenical council at the forefront of my mind, living as I do in a time similar to the iconoclastic crises. I do not seek to interpret its doctrine regarding art and tradition beyond what its words actually say; indeed, what they actually say is bold enough.”

“Little” Picture Book

Having discovered such a deep foundation in the craft and tradition of religious art, Mitsui was emboldened with equal parts humility and confidence to launch his newest project, the Summula Pictoria, as an attempt to illustrate these same aesthetic and theological principles—literally—in what he hopes will be the definitive reference work on religious art in the 21st century.

“I hope to undertake this task in the spirit of a medieval encyclopedist, who gathers as much traditional wisdom as he can find and faithfully puts it into order,” he says in a statement at his website. “I want every detail of these pictures, whether great or small, to be thoroughly considered and significant.”

As for the arc and expanse of the project, Mitsui says he hopes to accomplish the work in about 15 years.

“Over fourteen years, from Easter 2017 to Easter 2031, I plan to draw an iconographic summary of the Old and New Testaments, illustrating those events that are most prominent in sacred liturgy and patristic exegesis,” he notes. “The things that I plan to depict are the very raw stuff of Christian belief and Christian art; no other subjects offer an artist such inexhaustible wealth of beauty and symbolism.”

The name for the project, Summula Pictoria, communicates the effort’s breadth and modesty: 235 full-colored, double-sided pictures—each no bigger than a page in a book—drawn with metal-tipped dip pens, paintbrushes, and pigment-based inks, on calfskin vellum. The project, Matsui says, while ambitious, seeks to embody everything he wants to say about religious art.

“When I look back on my career, I want to be able to say, I drew the life of Christ and the scenes of the Old Testament that I think are the most important liturgically and, in the Old Testament pictures, as prefigurements for the most important liturgically and theologically significant events of the Bible.”

Mirroring the liturgy, the pictures will be drawn with the same telltale Gothic economy of detail that has informed all Mitsui’s work.

“I want to make everything that goes into each picture significant and don’t want it to be merely ornament,” he says. “I won’t put something in because this backdrop would look nice with sunflowers in it. I want every element to convey something—to place it in its actual location.”

The project will also strive for the same popular appeal that has been a hallmark of Mitsui’s style.

“My hope is that [the Summula Pictoria] will be useful to anyone who wants to make religious art, or to understand it,” he states on his website. “My idea is not to make a scholarly text or a university course; it is to offer, free of charge, something more accessible, comparable perhaps to a cookbook in which a professional chef shares his recipes.”

Setting up a website to chronicle this cookbook-in-the-making, Mitsui invites the public to visit his blog, danielmitsui.blogspot.com.

At Home—Yet Not Home Yet

Having found a place to call home in rural Indiana, Mitsui knows that his geographical identity is not nearly as important as his artistic identity and, ultimately, his supernatural destiny.

“Sacred art,” he notes in his August lecture at St. Cantius Church, “does not have a geographic or chronological center; it has, rather, two foci, like a planetary orbit. These correspond to tradition and to beauty; one is the foot of the Cross; the other is the Garden of Eden.”

For more information about Mitsui’s artwork or to contact Daniel Mitsui, visit his website: www.danielmitsui.com.