Evidence Challenges the Narrative of Decline Regarding Lay Liturgical Participation in the Middle Ages

Despite the wealth of scholarship pertaining to liturgical participation among lay medieval Christians, the narrative of medieval liturgical decline is enshrined in most histories of Christian worship. Indeed, the general story—as it is related in formal courses in liturgical history at seminaries, colleges, and universities—proceeds as one of decline.

The narrative of decline progresses as follows. In the early Church, participation in the Eucharist—including reception of the Eucharist—was normal for all Christians. As the Church became more clericalized and as the doctrine of real presence developed, Eucharistic participation by the laity declined. Medieval piety was expressed through ocular communion in which lay men and women would communicate spiritually by gazing upon the Host at the sounding of the sacring bell. Abuses occurred, such as lay men and women running from church to church just to see the Host. Because of architecture, the silent Canon, the use of Latin rather than the vernacular, and the advent of rood screens, it is assumed that lay people did not understand what was happening in the liturgical rites of the Church. Their participation was superstitious, perhaps, even compulsory, but it was not an active or intelligent participation. This non-active participation became enshrined in Catholicism at the Council of Trent, lay people inserted an array of devotions into the Eucharistic celebration like the rosary, and only the 20th-century liturgical movement and the reforms of the Council restored liturgical worship to its original purpose as the sacrifice of the whole Body of Christ.

This narrative contains some truth. A lack of reception of the Blessed Sacrament was concerning to medieval Catholic clerics, canonists, and theologians. The requirement to confess one’s sins and to receive the Blessed Sacrament once a year, decreed at the Lateran Council IV in 1215, is evidence that the Church wanted lay people to consume the Body of Christ more regularly. Thomas Aquinas’ own theology attends to the Eucharist as the presence of Christ, which is to be consumed in the Eucharistic banquet. Even if St. Thomas did not imagine that lay people might regularly receive the Eucharist each day in the 20th century, the meal dimension of the Eucharistic sacrifice is integral to St. Thomas’ poetic account of the Blessed Sacrament in the hymns he composed for Corpus Christi. The liturgical movement of the 20th century also strove to attune men and women to an active participation in this sacrifice of Christ, one in which the lay faithful received the Blessed Sacrament during the Eucharistic liturgy proper.

The modern liturgical movement was thus not a unique event in the history of liturgical development. An emphasis on participation in the liturgical rites by lay men and women was a persistent concern in late medieval life, and not just among the Church leadership, as mentioned above. The popularity of lay Mass books with commentaries on the Eucharist, the presence of Lay Book of Hours well before the Reformation, and the flourishing of the arts in late medieval Catholicism testifies to a robust desire for participation in the rites of the Church.

This medieval sense of participation is not precisely the same that many Catholics emphasize today. And it is here that lay medieval practice may be salutary for the Church in the 21st century. The purpose of this essay is to interrupt this narrative of decline, attending to the kinds of participation that were desired among lay medieval Catholics. Participation happened, and it was primarily social and aesthetic. The goal in this essay, therefore, is not to make the Church today into a medieval village parish or monastic community. The reformed Rites of the Church presume a distinct kind of participation by lay men and women, including involvement in Eucharistic dialogues and chanting the Mass Propers. But intelligibility of such texts and actions should not be the exclusive way of assessing lay Eucharistic participation. The social and aesthetic dimensions of liturgical prayer also must be considered. The way that we tell the history of liturgical evolution (or perhaps de-evolution, based on the story of decline) is not just evidence of bad history but a theological and philosophical assumption about participation. This assumption not only skews the true history of the liturgy but it also proves untrue to what it means to be a human being.

The Social Dimension of Lay Participation

Cracks in the narrative of decline within liturgical history have surfaced initially through the work of social historians. Two such historians, John Bossy and Virginia Reinburg, have argued that lay participation in the Eucharist was common, but it was not equivalent to clerical participation. Bossy’s 1983 article, “The Mass as a Social Institution 1200-1700,” argues that lay men and women participated in the Eucharistic liturgy as a social drama, which brought peace into the community of believers. Liturgical commentators understood the Canon of the Mass not only as an occasion for Eucharistic consecration but as the honoring of God and the saints, praying for the living and the dead, and asking God that the sacrifice of the Mass might relate to the needs of the ones praying the Mass.[1] Lay participation in the Eucharist often pertained to these three dimensions of the Canon.

Bossy argues that even if lay people did not fully understand Latin, or have access to the Roman Canon, they were surely aware that the Mass was a sacrifice of Christ for the benefit of the living and the dead. The practice of interceding for the dead was not just a religious custom but integral to medieval life. Bossy writes, “The devotion, theology, liturgy, architecture, finances, social structure and institutions of late medieval Christianity are inconceivable without the assumption that friends and relatives of the souls in purgatory had an absolute obligation to procure their release, above all by having masses said for them.”[2] Praying for the dead, especially after the consecration when Christ was present upon the altar in the Blessed Sacrament, was a regular practice for the devout.

And yet, as Bossy notes, liturgical participation was not reserved exclusively to praying for souls in purgatory. The regular celebration of the Mass also brought peace into the community celebrating the liturgy. The yearly reception of the Blessed Sacrament was a time of great festivity within the rural parish. Men and women would receive the Blessed Sacrament, as well as non-consecrated ablution wine, and then would proceed to a parish or fraternity feast.[3] Even if Holy Communion were not received regularly at Mass by the lay faithful, the pax board established Eucharistic solidarity among the community. Having witnessed the sacrifice of Christ upon the cross, men and women in their turn kissed this decorated board as it was passed among them, receiving the peace of Christ from the altar. This peace was to unite them into a Eucharistic fraternity.

Virginia Reinburg’s “Liturgy and Laity in Late Medieval and Reformation France” advances the argument of Bossy. She challenges the claim that lay men and women had no intellectual understanding of the Eucharist, arguing that this perspective is drawn primarily from the critique of both Protestant and Catholic reformers. She contends that the Mass was meaningful for lay men and women “because it was conducted in a ritual language of gestures and symbols they knew from secular life.”[4]

Most liturgical historians look to the books of clergy to assess lay participation. Reinburg notes that this is the wrong place to look. Lay prayer books reveal the distinct practices of lay men and women during the Eucharistic liturgy. Even if the Gospel was not understood by the lay faithful, being read in Latin, nonetheless the lay person was urged to stand and worship at the reading of the Gospel because the power of God’s word transcends understanding.[5] To stand, as showing respect, was familiar to the lay faithful from their daily interactions in society.

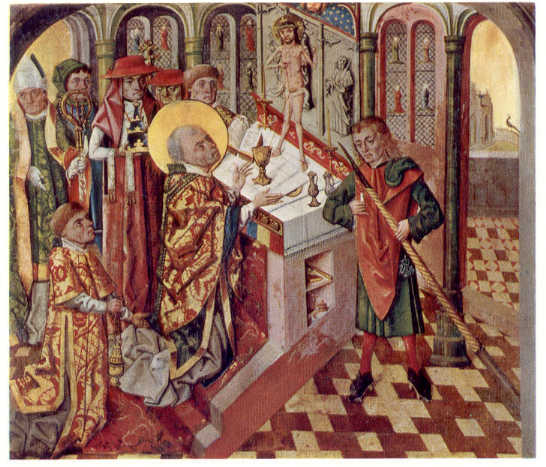

Further, the ritual actions surrounding the elevation of the Host were intended to draw the attention of the lay faithful to the awesome meaning of Eucharistic worship. The high elevation of the Eucharistic Host, on the part of the priest, was meant to facilitate lay participation rather than discourage it. The choir screen was sometimes opened at this time, and there was the ritual use of both bells and candles.[6] The visual experience of this moment of elevation was “built upon layers of visual memories associating the elevation with the crucifixion, and with the actual presence of Christ among those attending mass.”[7]

Even the pax board, for Reinburg, was intended to facilitate deeper Eucharistic participation among the lay faithful. Because of the gravity of Eucharistic reception, few would regularly receive the Host. And yet, the kiss of peace as mediated through the pax board and the reception of blessed and non-consecrated bread at the conclusion of Mass was available to all those attending Mass.[8]

According to social historians, liturgical participation of laity was simply part of medieval life. Not every lay medieval Catholic was devout. Surely, some did engage in religious practices as a form of magic or superstition. But, as a rule, there was an understanding of the Mass as a sacrifice that united the lay faithful “with God, the Church, and each other.”[9] The participation was not equivalent to clerical participation, but participation was active insofar as it involved lay men and women in the social life of the Eucharistic community.

The Aesthetic Dimension of Lay Participation

The aesthetic dimension of the liturgy is often misunderstood, even by medieval historians, who tend to perpetuate the assumption that the aesthetic culture of the liturgy was the “Bible for the illiterate.” The literate monk can participate in the rites of the Church, read manuscripts, while the illiterate lay person is catechized through stained glass windows and altarpieces. This assumption is problematic because it presumes that the aesthetic dimension of the liturgy—the act of beholding—is purely a passive phenomenon, reserved for lay life. Art and music historians have begun to deconstruct this assumption, showing that the act of beholding—whether through the eyes or the ears—is a supreme occasion of participation for both cleric and lay person alike.

Many liturgical historians presume that both seeing and hearing are purely passive activities. Implicit in such presumptions, we must infer that these historians see it as an act of non-participation to behold a rite that is unfolding within a space or to listen to a polyphonic setting of the Sanctus. This assumption takes as normative a modern approach to both sensation and knowledge. Real knowledge is an internal phenomenon, whereas the act of sensation is at best a passive reception of the senses. In her book Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages, Suzannah Biernoff provides an alternative account of sensation based in the medieval optics of Roger Bacon (1220-1292). Medieval optics understood any act of seeing as both passive and active. The eye does not just behold from a distance but engages in a physical encounter between the perceiver and the object perceived. It is through the eye that the physical world penetrates the body of the one perceiving. Biernoff writes, “As a medium and meditator between the sensitive soul and the sensible world, the eye, like the skin, is both part of us and external to us, …the flesh of the skin and eyes constitutes a permeable membrane and not—or not only—the body’s border.”[10] The eye does not participate in a distant gaze but communes or touches the object to which it directs its attention.

This optical theory was not known exclusively by literate clerics. Evidence shows that many of these same clerics shared this theory with their congregations, its consequences suffusing both monastic and lay sermons at the time. For example, the custody of the eyes was so essential, because to gaze erotically upon the human body or food was an embodied act. It was a physical encounter between the one who looks and the object or person. The eyes are the windows of the soul, because they are penetrable by the outside world, allowing the external world a port of entry into the soul. And yet, not all seeing was bad seeing. If the pornographic gaze leads one into sin, there is also a redemptive gaze. As Biernoff shows, the increased attention in late medieval devotional life upon gazing on the image of Christ crucified or looking upon the Host is not fundamentally about distance but proximity. Beholding is an act of communion between the seer and the object of sight—and it is a communion in which salutary images heal men and women.

Of course, not just the eyes are involved in this act of beholding, but all the senses. Liturgical historians have tended to deal almost exclusively with texts. And yet, as Eric Palazzo shows, one cannot understand medieval liturgy as primarily a textual phenomenon. In other words, liturgical participation is not exclusively for the literate. Rather, liturgy is intended to enable the participation of all persons. He writes, “in addition to its strong theological connotations and meanings, the liturgy was by its nature a ‘synthesis of the arts,’ where all the senses are appealed to, since man, made of a soul and a body, is himself an image, a ‘representation’ of the church in its theological sense as well as its material dimension.”[11] One participated in an ecclesial identity through the act of sensation in the liturgy.

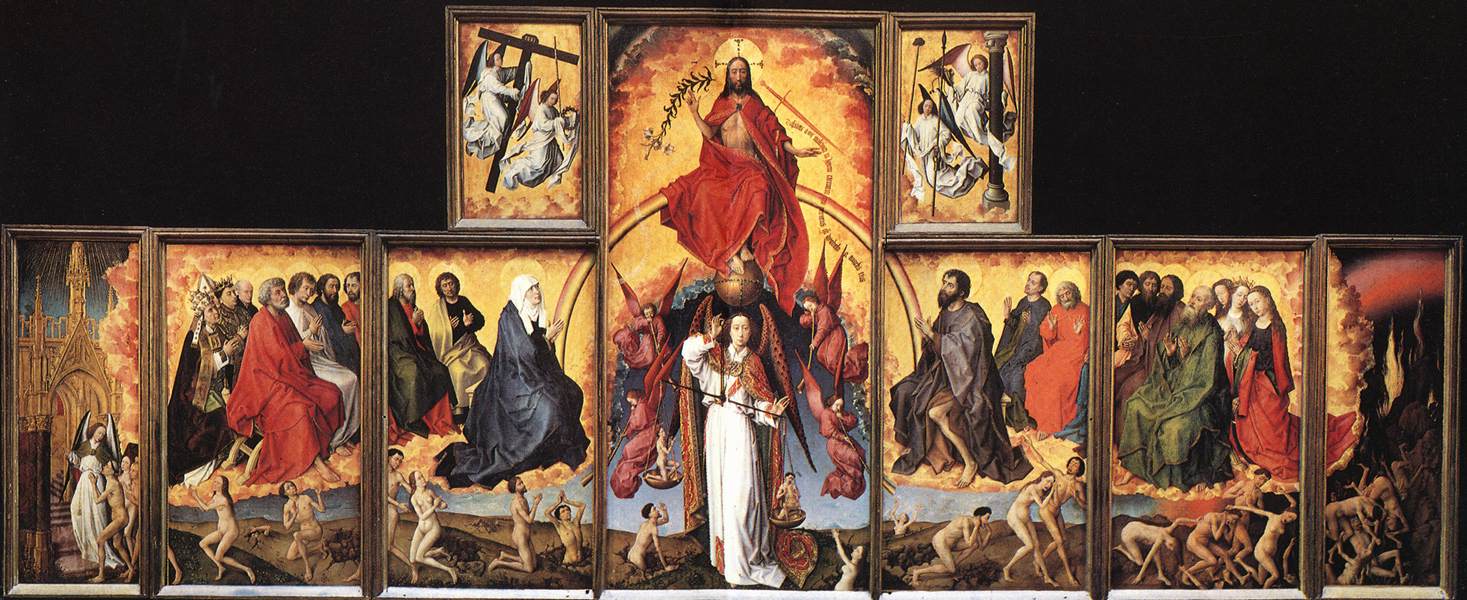

The artistic monuments of the medieval liturgy should not therefore be understood as exclusively for the illiterate. Instead, aesthetics is the privileged mode by which the human person as body-soul is enabled to participate in the liturgical act. The altarpiece is not reducible to educative scenes but enables men and women to participate visually in the sacrifice of Christ in the context of an image to which a variety of devotional registers are associated.[12] Likewise, the singing of polyphonic music in later medieval liturgy was part of this act of dramatic beholding, creating an aural backdrop by which the wondrous elevation of the Host might be connected to salvation history such as the moment of Annunciation where the Word becomes flesh and dwells among us.[13] Polyphonic music often drew upon melodies from popular love songs, allowing erotic desire to be directed toward Eucharistic beholding. From this context, is it a surprise that the women mystics of Helfta, such as the Benedictine nuns Mechthild of Hackeborn (1241-1298) or Gertrude the Great (1256-1302), produce rich nuptial imagery around the act of liturgical contemplation? Antiphons blossom into rich images of Christ, coming to redeem in his very flesh the praying nun.[14] The texts that were written at Helfta (near Leipzig, Germany) would be translated into the vernacular for lay readers, inspiring later Eucharistic and liturgical devotion throughout Europe.

Lay participation in the entirety of the liturgical life of the Church, not just the Mass, therefore, was facilitated through the aesthetic culture of the medieval Church. The idea that lay people were passive receptacles during the medieval period is increasingly untenable based on the work of musicologists, art historians, and those retrieving the liturgical poetics and rhetoric of women mystics who influenced later vernacular literature.

Past Present

As noted in the introduction, the purpose of this essay is not to force us back into a medieval worldview. Nor is it to offer a critique of the reformed rites of the Second Vatican Council that emphasized intelligibility of sacramental rites. Rather, it is to offer a correction to historians who tend to misread what constitutes lay participation in medieval life for three major reasons.

First, these historians focus almost exclusively upon liturgical texts. Liturgical history is not entirely textual, and further when dealing with lay piety, liturgical texts will not reveal much. Lay participation is facilitated through devotional manuals, social norms, public rituals, and the material culture of the medieval West. Lay participation in medieval times unfolded more in these media than the ritual books of the Roman Rite—and may even do so today.

Second, these historians presume a particularly modern—and, indeed, problematic—account of participation in the first place. According to these historians, participation necessitates intellectual recognition of what is happening. Therefore, so many liturgical catechists after the Council continue to say, “If people only knew what they were doing, then everything would be great.” Such attitudes reflect a thin sense of participation, focused almost exclusively on grasping the intellectual context of the liturgical act. Participation includes initiation into a social drama, as well as the involvement of the totality of the senses. Seeing is not passive. Hearing is not submissive or inactive. Medieval optics and theories of the senses have more in common with contemporary phenomenologists of the senses like Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) than exclusively modern accounts of sensation drawn from Enlightenment philosophy.[15] If people do not delight in the liturgy today, it may be because there is little to behold.

Third, liturgical history rarely examines its theological or philosophical assumptions. Because it is inattentive to intellectual history, it judges eras based upon a series of assumptions that do not resonate with the life of that period. It is true that medieval lay folk did not participate in the liturgy in the way that we do. But that does not mean that there was no participation. Although eschewing a golden era, such scholars continue to stand outside of history, assessing as a neutral referee what is good and bad. The referee is not as neutral as he or she purports to be. Rather than treat liturgical history as gathering evidence for a future reform—whatever that reform is to be—one should enter sympathetically into the worldview (as best as possible) of those one is studying. Some degree of neutrality is needed, especially when studying eras that have been continually underappreciated such as medieval liturgy or Baroque reforms.

If we learn to read correctly the nature of medieval participation, it is possible that we will discover that it has something to teach even those of us who regularly celebrate the reformed liturgies of the Second Vatican Council. And from that insight may come forth a fresh ressourcement in which we perceive the Spirit of God acting in what many too often judge as the darkest of ages. We need not make the world medieval again. But we must learn to appreciate the medieval world if we are to participate actively in the liturgy ourselves.

- John Bossy, “The Mass as a Social Institution 1200-1700,” Past & Present 100 (August 1983): 36. ↑

- Ibid., 42. ↑

- Ibid., 54. ↑

- Virginia Reinburg, “Liturgy and Laity in Late Medieval and Reformation France,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 23.3 (Autumn 1992): 529. ↑

- Ibid., 530. ↑

- Ibid., 533. ↑

- Ibid., 537. ↑

- Ibid., 539. ↑

- Ibid., 541. ↑

- Suzannah Biernoff, Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 90. ↑

- Eric Palazzo, “Art, Liturgy, and the Five Senses in the Early Middle Ages,” Viator 41.1 (2010): 27. ↑

- Beth Williamson, “Altarpieces, Liturgy, and Devotion,” Speculum 79.2 (2004): 341-406. ↑

- M. Jennifer Bloxam, “Music and Ritual,” in The Cambridge History of Fifteenth-Century Music (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 518-520. ↑

- Anna Harrison, “‘I am Wholly Your Own’: Liturgical Piety and Community among the Nuns of Helfta,” Church History 78.3 (2009): 549-583. ↑

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Donald A. Landes (New York: Routledge, 2012). ↑