In September of 2020, the Benedictine monks of Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey in Oklahoma revealed a new stone sculptural group over the central entry portal of their abbey church. Seven years in the making by artist George Carpenter, a self-trained stone carver, it engages deep traditions of medieval architecture proper to the abbey’s French origins, which in turn reach back even further to the visions of God found in the Books of Ezekiel and Revelation. But as a new work of art, it testifies that today’s revival of Catholic art has reached a new high. Not only has the artist mastered the craft of stone carving, but he has also fashioned in this inert material a sacramental revelation of the divinity of Christ and the sanctity of the Four Evangelists.

Clear Creek Abbey

Located about 55 miles from Tulsa, Clear Creek Abbey was established as an American outgrowth of the Abbey of Notre Dame de Fontgombault, a French foundation dating to 1091 but which has been a Benedictine abbey of the Solesmes Congregation since 1948. In the 1970s, a group of American students in the University of Kansas’ Pearson Integrated Humanities Program became interested in monastic life, visited Fontgombault, and entered as monks with the hope of someday returning to establish an American foundation. Though it took several decades, they established the American priory in 2000, now officially raised to the status of an abbey. Little by little the abbey’s community and buildings have been taking shape following a master plan by noted classical architect Thomas Gordon Smith. With a slogan from the beginning which read “Building something beautiful for God to last a thousand years,” the progress of construction has been slow but steady, often using traditional hand-crafted methods.

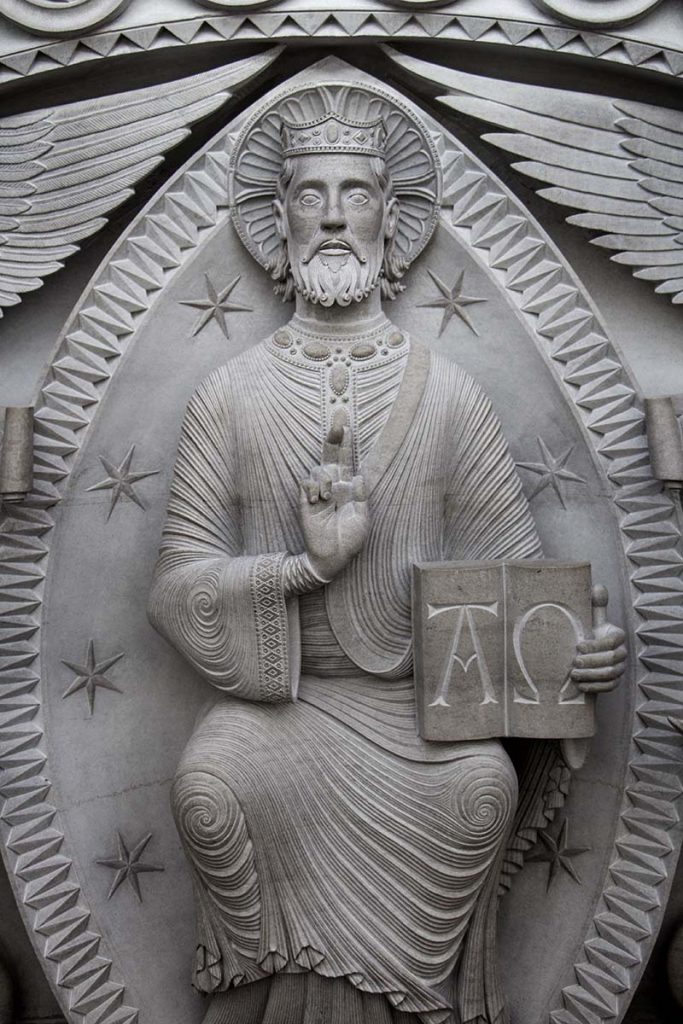

As the abbey church progressed, the time came for developing the sculptural program of the entrance portal. For several years, sculptor Andrew Wilson Smith, son of the original architect, labored on a horizontal stone beam known as a lintel, depicting the twelve apostles. The zone above the lintel but below the portal’s arch is known as a tympanum, an area known for sculptural richness in France’s great Romanesque churches of the 11th and 12th centuries, frequently on monastic churches with architectural and religious programs remarkably similar to those of Clear Creek today. In a video interview with David Niles and Adam Minihan of The Catholic Man Show, Carpenter explained that he used many French portals as inspiration, but in particular, Chartres Cathedral provided the model for the subject of Christ surrounded by the Four Evangelists, while the central portal of the French Abbey Church of Vezelay inspired the stylistic mode of representation.

Sacramental Building and Heavenly Jerusalem

In the longstanding Catholic tradition, a church building is a sacrament of heaven, called in scripture the “heavenly Jerusalem,” a walled city where the saved enter through great gateways. The doorways of a church building, then, are not simply holes providing for the necessity of entrance, but portals, sacramental expressions of the nature of the act of entering. Accordingly, these great portals frequently show Christ in heavenly majesty as the judge who determines who enters through this porta caeli, the gate of heaven.

Clear Creek’s tympanum draws from several moments in scripture where Christ is shown in glory surrounded by four winged creatures taking the form of a man, an ox, a lion and an eagle (Ezekiel 1:10; Revelation 4:6-9). As early as the 2nd century, St. Irenaeus understood these creatures to represent the Four Evangelists, an idea echoed by both Augustine and Jerome. The man signifies Matthew, whose gospel begins with the human genealogy of Christ, while the ox points to Luke, who begins his account of Christ’s life in relation to the animal sacrifices of the Jerusalem Temple. The lion indicates St. Mark, whose gospel begins with the voice crying like a lion in the wilderness, and lastly, the eagle speaks of St. John, whose lofty theology soars with contemplation of Christ’s divinity. So whether in 12th-century France or 21st-century Oklahoma, the theological reality remains the same: Christ is the Door and the Judge, and though he reigns in heavenly glory, he is encountered by everyone who enters a church.

Divinized Reality

The challenge for any liturgical artist is to make something more than an earthly representation of a bearded man in ancient costume surround by four natural-looking creatures, but to make the stone figures sacramentally transparent to spiritual realities while retaining their naturalistic qualities. And here the new tympanum truly shines.

Both Athanasius and Irenaeus theologized that God became man so that man might become God. In other words, God entered into fallen humanity so that he might enroll all of creation into the process of divinization, meaning that like Christ’s resurrected body, all would become glorified and perfected without losing their essence. A sculptor trying to draw heavenly realities into earthly time and space therefore must not only understand this theological reality but be able to render it in stone. Here the inspiration from the abbey at Vezelay comes into play, where medieval artists had developed an iconic method of representation, using stylized forms to indicate that all is taken out of fallenness and brought to perfection. Bodily gestures are idealized with ballet-like movements, the drapery’s folds are regularized with swirls, spirals, and geometric shapes, and hierarchies are indicated by each figure’s size and location.

Heaven in the Twenty-First Century

At Clear Creek, Carpenter’s mastery of craft is on vibrant display. In his Catholic Man Show interview, he discussed the technical requirements involved in making the sculpture, which is composed of four separate pieces of stone which had to appear seamless and be designed to shed water which otherwise could freeze in winter and damage the piece. Many quarries were investigated, but the work was ultimately carved of a marble-like stone from Arkansas which allows for fine detail, a high polish, and resists degradation from weather. As a self-taught stone carver, Carpenter began with a certain amount of trepidation, beginning with the rosettes that line the arch, then carved the evangelists, leaving Christ for last. Since the image of Christ was planned from the beginning to step forward from the other four figures, the carver explained the almost theological process in which the carving of the four surrounding figures had to be consistently measured off of the location of the yet-to-be-carved Christ, making him the literal touchstone of the entire design process.

Christ appears in the center of the composition seated within a star-filled mandorla, an almond-shaped marker of the insertion of heavenly realities into earthly space. His jeweled crown and garments speak of his kingship, but also the glory of heaven, described throughout scripture as composed of gems and gem-like radiance. His posture and gesture of blessing are stiff and hieratic, and his expression stoic. This sense of heroic calm is meant to establish Christ as human but without human frailty, allowing the majesty of his divinity to shine through. This requires a kind of ascetic discipline from the viewer, who is asked not simply to be satisfied with his own humanity, but rise above it and grow into divinized perfection. Yet the severity of Christ’s “Phidian calm,” named for Phidias, the ancient Greek sculptor who developed it, is relieved and made lively by the dynamic multiplied lines and swirls of his garments. Christ’s beard, too, is composed of idealized soft curls ending in repeated spirals. The perfection of Christ’s divinity therefore finds a dynamism of existence in perfected creation. Christ is both divine and human, and as the New Man, even his facial hair obeys and conveys that ontological reality.

The Four Evangelists follow suit, where the lion’s mane of the St. Mark image flows like perfect rivulets and his musculature, while in one sense believable, defies literal representation. Together with the ox, he defies gravity by remaining upright despite neither of his front legs reaching the ground, and his tail wraps gracefully around his rear leg and terminates in a tuft of fur that reads like fire. His ribs express the corporeality of bodily structure, yet their stylization gives a suggestion of taut, athletic energy. Like the ox and the eagle, the lion shows an eschatologically ferocious face, recalling C. S. Lewis’ description of the lion Aslan, who is not safe, yet also not fearsome, because he is good.

The winged creature with the human face holds a scroll with the Latin inscription “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” a reference to the Sermon on the Mount, found only in St. Matthew’s gospel. Like the other evangelists, the figure is deeply undercut, meaning much stone is removed from behind, thereby placing the figure in the depth of the arch, a technically demanding feat giving stone pieces the appearance of delicate weightlessness. Unlike the ferocity of the other evangelists, the Matthew figure’s human face gives a rich expression of his interior mind and emotions. Despite his idealized clothing and hair, his face betrays both fascination and holy fear of the Lord, with an expression of mouth and eyes at once still and yet intensely focused on Christ in glory.

Making Stone Speak

When looking at a completed work of art, especially one which conveys both earthly and heavenly intensity, it is easy for the viewer to forget one simple fact: it was once an inert mineral deposit in the ground, placed providentially by God’s agency eons ago, waiting for its liturgical telos, or final purpose. Because God shared something of his own creative power with humans, he established the calling of the artist to see beyond mere stone, and join intellect and will with the inspiration of the Holy Spirit to act as Christ. Christ took on matter in the Incarnation to reveal God to the world, and the Church continues to reveal him through the sacraments, where bread and wine become the revealers of Christ’s Body and Blood. In an analogous way, an artist takes stone and makes it not only a reminder of Christ’s existence, but a bearer of Christ’s presence. At Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey, a new work of art has drawn creatively and deeply from the Church’s great tradition. But more importantly, it allows ordinary Christians to see the face of God.

For a complete collection of images, visit Clear Creek’s media gallery.