In order to adhere to COVID-19 guidelines regulating the number and spacing of people at gatherings, some bishops have chosen to hold this year’s ordinations outside. This author attended one such ordination in a nearby parish’s picturesque prayer garden. The organizers did an excellent job preparing a makeshift sanctuary and nave, and on the day of the event the weather fully cooperated. Everything came together so nicely that one could not help wondering, “Is this the new normal?” The question seemed plausible at first. Yet as charming as the scene initially appeared, it was difficult to suppress a further question: “Yes, but should this be the new normal?”

These ordination experiences, along with an untold number of Holy Masses celebrated outdoors this year, force us to ask why the Catholic Church ordinarily celebrates her liturgies in the enclosed sacred space of a church. In what follows, we will not approach this question by appealing to rubrics or laws concerning the liturgy. Rather, we will first establish the human need for dedicating space to the sacred before going on to suggest why this human need further requires that it be indoor space that is so dedicated.

Why does the Catholic Church ordinarily celebrate her liturgies in the enclosed sacred space of a church?

A Natural Fit

The human desire to dedicate space to the sacred fits with nature’s tendency to pursue ends. This pursuit furnishes what we humans need for our various purposes. The sun provides light for us from above in the sky. Depressions in the earth—rivers, lakes, and ponds—hold the water we need to drink. Rooted in the soil, plants produce the oxygen we breathe, and many of these same plants grow to be edible by us and other animals. The examples could be multiplied, but these suffice to make the point: Nature pursues ends, each of which requires a certain “dedicated space.” Human beings, made in the image and likeness of God, reflect this natural tendency: In man, we see a microcosm of creation as a system of things fulfilling divine purposes in particular spaces.

We imitate God by subduing the earth and using the resources it provides in order to establish permanent, necessary, and dedicated spaces. We set aside such spaces first for ourselves and our families with the construction of homes, garages, barns, shops, fields, pastures, and water storage systems. These buildings are further divided into smaller dedicated spaces that are even more permanent, necessary, and purpose-oriented. For example, it is difficult to do much else with closet space than to use it as a closet. We do not serve supper in bathrooms. Finally, we leave our automobiles parked in the garage, not the living room. Put simply, nature—and human nature—tends to say, “A place for everything and everything in its place.”

Outside and inside are qualifying differences with respect to both purpose and place. For various reasons, we human beings do not do everything outside and in the open. Whether it be on account of weather, the desire for privacy, the need for quiet, or any of a host of other reasons, we often find ourselves drawn indoors. On a more practical level, the outdoors fluctuate and change too often. Grass grows, temperatures rise and fall, wind varies, and clouds come and go with and without rain. An indoor space may lack the beauty of nature, but it offers a more predictable and stable environment to conduct our business and live our lives. In this sense, going inside adds a deeper dimension of permanence that allows us to dedicate space for particular activities. We sleep in bedrooms, perform personal hygiene in bathrooms, prepare meals in kitchens, and eat food in dining rooms. These spaces give us the assurance of having the necessary space to carry out our daily activities.

Once these spaces have received their permanent, necessary, and dedicated purpose, human beings attach some level of intimacy to them. An unidentified stranger may not be invited onto our property, for we have not yet allowed him into our hearts as a friend. Meanwhile, a family friend may be permitted to walk freely onto the property without any special invitation. Nonetheless, for some families the home would still be off-limits to all outsiders. Even within the family, interior spaces acquire levels of intimacy from which certain people are excluded. For example, the bathroom attached to the master bedroom would be typically off limits to anyone except the husband and wife. In other houses, a home office would be off limits to anyone—and especially children—without either prior approval or an invitation, most especially during work hours. Finally, a chest of drawers may be left unlocked, but the family members understand these to be deeply interior spaces holding personal belongings not meant for just anyone’s eyes.

Supernatural Dedication

The activity of establishing ever-deeper levels of permanent, necessary, and dedicated space reaches its culmination when we reserve such space for the worship of God. Some might initially counter that this is unnecessary. After all, God is everywhere, so why would we need to devote any space to him? Such an argument forgets that we cannot appreciate God’s presence everywhere unless we can appreciate it in the here and now. It is partly to orient attention to the presence of God everywhere that we establish permanent, necessary, and dedicated spaces for divine worship in the here and now.

It is partly to orient attention to the presence of God everywhere that we establish permanent, necessary, and dedicated spaces for divine worship in the here and now.

We human beings need some particular space to worship God so that we may learn to understand that all space—the whole cosmos—is a temple. We could not hope for a clearer biblical explanation of this truth than Cardinal Ratzinger’s The Spirit of the Liturgy. In the second chapter of that book, Ratzinger shows how the Book of Genesis presents the six-day work of creation as the divine construction of a cosmic temple. For the sacred author, the world is a single vast place of worship. By the same logic, the Jewish Temple represents the God-given purpose of the world, which is to be a temple of cosmic praise.

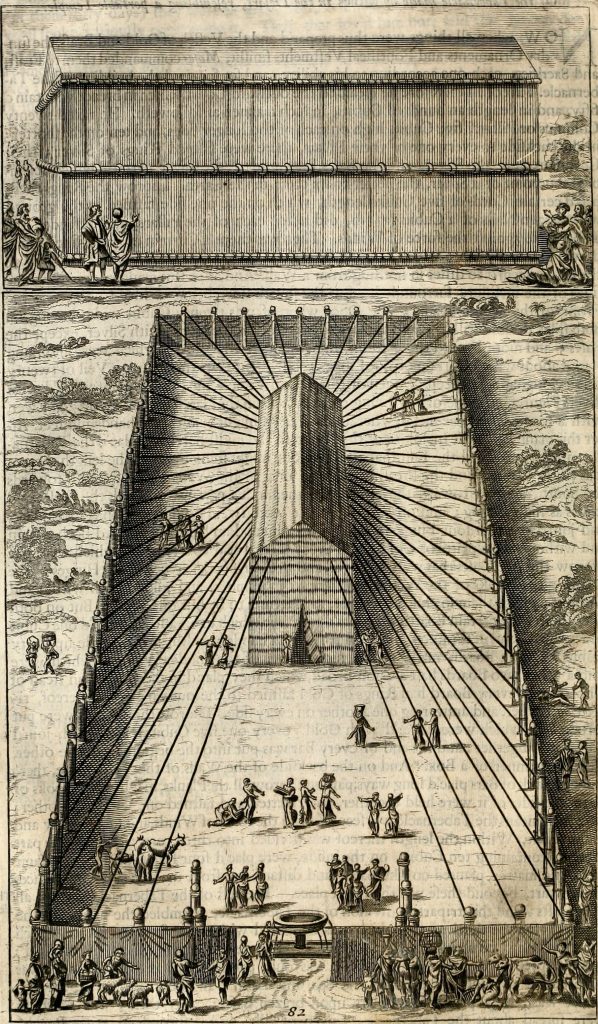

Ratzinger takes up the same theme in the first chapters of The Spirit of the Liturgy; however, there he connects the Exodus, worship of God, and the Promised Land. It was not sufficient for God that the Hebrew people take a few days off from their slave labor to worship him in Egypt. God insisted that his people leave Egypt and go to a special place set aside for divine worship. As Moses leads the people in passing over from Egypt to the Promised Land, the Hebrews stop at the permanent, necessary, and dedicated place of Mount Sinai to receive the Decalogue. Once the people had arrived in the permanent, necessary, and dedicated place that is the Promised Land, God intended to be housed in the enclosed but transitory Tent of Meeting. In God’s Providence, the Tent of Meeting prefigured the coming of a Messiah who would lead the people to true worship. True, God initially resists King David’s desire to give him the permanent, necessary, and dedicated space of the Temple. Nevertheless, the eventual construction of the Temple could be said to complete a trajectory begun with creation itself. Significantly, even this space underwent further degrees of dedication, as strict limits were placed on which people could enter the various areas and on the frequency with which they could do so.

God Lives Here

The Temple represents a shift in the Hebrew people’s worship of God from a dedicated but transitory space to a permanently dedicated space. Today, the primary way in which we continue the tradition of permanently enclosed and dedicated spaces for the communal and personal worship of God is by building churches. While many Catholic families set up home altars or prayer corners in their houses as an aid to prayer, even the Catechism of the Catholic Church (2691) mentions these options only after discussing the primary and proper location of prayer: the church. Home altars and prayer corners should be in every Catholic household, for they encourage families to join together in prayer and to worship as a domestic church. Nonetheless, the church building retains its primacy: It alone allows the entire people of God to assemble as a parish community representing the whole Mystical Body of Christ.

In our churches, as in our homes, we further establish permanent, necessary, and dedicated spaces for particular uses, such as fonts for Baptism, confessionals for Reconciliation, and altars for Holy Mass. Also, in the same way that a home is divided into inner spaces with varying degrees of intimacy—from the entryway to the dining room, and from the bedroom to the bathroom—we see analogous distinctions in a church. Talking may take place in the narthex, but not the nave. While all may pray in the nave, only the priest and his ministers are allowed to enter the sanctuary during the celebration of Mass. Traditionally, only the ordained had access as well to the most intimate space of the tabernacle.

Creation’s Four Walls

It might seem that going inside such an enclosed space of prayer hampers one’s vision of the surrounding world. However, as St. Maximus the Confessor teaches in his work The Church’s Mystagogy, the parts of a church represent all the parts of the cosmos, seen and unseen at any particular moment. Therefore, going inside a church gives man an experience of the whole creation in the microcosmos of the nave and sanctuary. From that one location in the church, man sees the entire universe represented with different signs and symbols that perfect, elevate, and divinize the natural. As we enter a church, we become part of the divine drama of man, made in the image and likeness of God and saved from eternal death by the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

The difference between the nave and sanctuary, for example, symbolizes the division between earth and heaven, while the sacred images draw us closer to the Church Triumphant of Heaven, whose victorious saints intercede for us. These and many other examples, too many to list here, underscore the following capital point: Precisely because the church building is a permanently enclosed and dedicated space, every surface and area of it can have a permanent and necessary symbolic meaning that, as St. Maximus shows, corresponds to some aspect of the divine economy that begins with creation and culminates with supernatural redemption. Such an arrangement would never be possible if our places of worship were merely dedicated spaces and not enclosed and dedicated places. The variation that the outdoors indisputably imposes also limits the outdoor space’s ability to represent, symbolize, and communicate so many mysteries.

It is true, of course, that outside spaces can also be structured for symbolic purposes. Think of formal gardens, which may have a quasi-sacred function, as in Zen Buddhism, or even shrines and grottoes in the Catholic tradition. Nevertheless, only a permanently enclosed space can represent the cosmos in its creation and salvation as a single, Christologically shaped whole. Only a permanently enclosed space can prefigure the new heavens and the new earth as God’s eschatological temple. Indeed, there is a real sense in which a permanently enclosed church is a better manifestation of the cosmos than the natural cosmos itself: The church building incorporates and elevates the natural to its supernatural destiny. This is one central reason why Catholic worship most fittingly takes place in churches—rather than in rock gardens or labyrinths.

Only a permanently enclosed space can prefigure the new heavens and the new earth as God’s eschatological temple.

Insider Information

This qualifying difference between outside and inside takes on a richer and deeper meaning when applied to human beings. In addition to living outdoors and indoors, human beings have and an exterior and an interior life. The interior life corresponds more to one’s actual self than the presentation our outside or exterior life sometimes portrays. Even more importantly for our argument, the interior life finds expression in the intimacy associated with the inner spaces of our homes and other buildings.

Man’s interior life finds expression in the intimacy associated with the inner spaces of our homes and other buildings.

The fact that the interior life is sacred is evident, even if we cannot immediately explain why it is so. The soul’s existence “inside” man seems to require that the soul, too, have a kind of sacred center. Not surprisingly, a man accesses the interior of his soul as he goes inside himself, but this interiority is itself dedicated to a sacred purpose and is tied to the manifestation of the divine presence. Teresa of Ávila, along with many other saints, speaks of the interior life using the analogy of moving from room to room: As one proceeds, one comes ever closer to the intimate center where the waiting Beloved resides. The more we enter into the permanent, necessary, dedicated, and enclosed sacred space of our souls, the more we know and experience the presence of God in us. Of course, the Blessed Virgin Mary stands above us all as the unique exemplar who “treasured all these things and pondered on them in her heart.” More than anyone else, Mary entered the deepest tabernacle of her soul, where the Word first took flesh in her and dwelt among us. It was there that she offered her spiritual sacrifice on the altar of the heart—the altar mirrored symbolically in the altar around which our churches are constructed.

To help us follow the example of the Blessed Virgin Mary and all the saints, churches give us an enclosed space leading us mystagogically into the sacred space of our souls. Entering a still church directs our minds and hearts away from the noise of the exterior to the silence of the interior. At the same time, the church connects the interior temple of our souls with the temple of the universe that the church itself represents in microcosmic analogy. Even the briefest of glances in a well-ornamented church gives the soul a full picture of the human drama. It reminds us that whatever problems, difficulties, or trials we face (coronavirus or otherwise), the Lord Jesus has won victory over them, for he is King and Lord of the universe.

Come on In…

Inspired by this confidence, we turn the eye of our soul inward and seek the Beloved in his throne room of our souls. Indeed, this experience should be and is the only normal encounter with our Lord and God and Savior Jesus Christ until the day he comes again to call us to the House of the Father, to the Temple he himself is, where we will live a new eternal normal with him, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and all the saints, forever and ever.