The Eucharist—being the risen Lord made really, truly, and substantially present in our midst—is the New Covenant. It is the memorialized and institutionalized moment in which Jesus made the New Covenant in his body and blood: “the blood of the [new] covenant” (Matthew 26:28; also Luke 22:20). The Eucharistic liturgy is where Jesus purposefully planned and institutionalized his real, true, and substantial presence from heaven to accompany and nourish (cf. Ephesians 5:29-32) the souls of the baptized after his bodily Ascension. Along with the oral announcement, the New Covenant was originally communicated ritually and liturgically and only secondarily became a written proclamation as well. The New Covenant writings—or “New Testament” writings as commonly called today—are therefore only properly understood, made relevant, and contextualized by the institutionalized ritual and memorial which Christ left with the Apostles. If one gets wrong the meaning of that ritual, he distorts the whole context of the written New Testament.

The Eucharist in Scripture

In the Eucharistic liturgy (cf. Revelation 21:22), which Jesus established to be maintained by the Apostolic succession (cf. Revelation 21:14; Matthew 16:19; 18:18), Jesus gives himself to be received for eternal life under the appearance of bread and wine (Matthew 26:26-28; John 6:52-58) for all the baptized. In the divine liturgy which Jesus institutionalized, separation of the bread [which becomes participation in Jesus’ risen body] and the wine [which becomes participation in Jesus’ risen blood] manifests the lamb of God that was slain (Revelation 5:6; 1 Corinthians 5:7-8; 11:26) “for the forgiveness of [daily/venial] sins” (Matthew 26:28; cf. Exodus 29:38-41; John 1:29). Separation of body from blood shows a sacrificial death which is being made available for participation and personal benefit: “Christ our paschal lamb has been sacrificed, therefore let us partake in the [ritual] festival” (1 Corinthians 5:7b-8a). Christ reigns bodily in heaven without suffering during the earthly memorial and festival, while truly extending his heavenly presence through the veils (cf. Hebrews 10:19-20) of bread and wine:

“In that day you will know that I am in my Father and you in me, and I in you” (John 14:20)…“we will come to you and make our home with you” (John 14:23; cf. Revelation 21:22-23). From heaven, Jesus uses the Eucharistic liturgy to communicate “eternal life” (cf. 1 John 1:3) from him as a “life-giving Spirit” (1 Corinthians 15:45; John 6:62-63) and to develop the vital union begun in baptism. Spoken at the Last Supper, John 14-17 is an explanation of what Jesus accomplishes in the Eucharistic liturgy even before it is fully realized in the permanence of heaven, and completed in our earthly lives. Revelation 21-22 reveals the Eucharistic liturgy to be the New Jerusalem coming down out of heaven (cf. Hebrews 12:18-24), by bringing the Lamb of God (cf. Revelation 14:1-5) into our midst, who gathers us and “takes us to himself, so that where he is we also may be” (John 14:3).

The Eucharistic liturgy—which Jesus initiated in the Upper Room the night before he died and so began the offering of his earthly body and human will (cf. Hebrews 10:9-10; Matthew 26:26-28)—was the beginning of his final self-offering that was completed on the Cross. The institution of the New Covenant is inseparable from the witness to Jesus’ suffering, death, and resurrection which is now contextualized and explained by the Gospels. Thus, the written Gospels, just like all other sacraments, are dependent upon the liturgical institution of Jesus’ body and blood (the New Covenant) and are at the service of witness to that institution upon which they depend and in order to communicate eternal life. Thus, the liturgy is the interpretive key to all authoritative proclamation of the good news (cf. John 3:16), and the written Gospels are secondary to (or “dependent on”) the liturgy’s primary proclamation that Jesus is the Son of God, who became Man, “so that man might become God” (St. Athanasius, CCC #460) according to grace; especially through the means Christ established liturgically: baptism for entrance into Holy Communion (cf. Hebrews 10:19-20) and sharing God’s “eternal life” (John 6:54).

Liturgy’s Life-Giving Principle

The only reason to consume the veiled body and blood of Christ in the liturgy is to receive “eternal life” from Jesus the “life-giving Spirit” (1 Corinthians 15:45) whose human flesh is now totally subject to his divine nature and his divine nature fully available through his human flesh and blood. “It is the Spirit that gives life, the flesh is of no avail” (John 6:63). Through Christ’s resurrection, the Eucharist is the life-giving and indestructible flesh and blood of God eternal and thus called by Paul “a life-giving Spirit” (1 Corinthians 15:45). Because of his indestructibility in the Resurrection, Christ is consuming and integrating us into divinity, “swallowing us in [divine] life” (cf. 2 Corinthians 5:4), in our reception of him at Holy Communion. This mystery and its power are only accessible through faith given from above, the infused supernatural virtue by which God is at work within our freedom “to will and to work” (Philippians 2:13) for our renewal in Christ Jesus (cf. Romans 12:1-2). This is our entrance into the Holy of Holies, Jesus Christ, seated at the right hand of the Father.

In the Incarnation, Jesus’ body had always been subject to his divine nature, but to accomplish his mission as the “last Adam” (1 Corinthians 15:45) and Messiah, the inherent grace of indestructibility was originally withheld (like in ‘sinful flesh’ cf. Romans 8:3) so he could experience our sufferings (cf. Philippians 2:5-8; Hebrews 5:8-10). Upon accomplishing his divine mission to bring a human will into the fulness of the Divine Will (cf. Hebrews 10:9-10), his humanity was allowed again to possess bodily indestructibility or immortality in Jesus’ resurrection from his perfect sacrifice. The sacrifice was perfect, not only because of Christ’s innocence and purity, but because a human can give no more of an “Amen” or “Yes” (cf. 2 Corinthians 1:19) to God in his human will than to the point of death after already enduring much torture. In Jesus’ true and total human surrender to God the Father (the obedience of love for the truth), indestructibility permeated his bodily life because of his great obedience of love (cf. Philippians 2:9-11) unto death. Death was “swallowed up in victory” (1 Corinthians 15:54) and that victory is now communicated through Jesus’ glorified body primarily in the Sacraments.

God and Man

The total surrender and obedience was accomplished through Jesus’ one-time bodily sacrifice which abolishes sin and separation from God. The separation of sin occurs through the weakness of the human will which does not know and love God: but in Christ it abides in God’s will: “This is eternal life, to know thee the one true God…” (John 17:3). Because Jesus was God the Logos, his human will was always one with and ‘inside’ the Divine Will by the Incarnation; “full of grace and truth” (John 1:14) by which he merited through his new human actions a share in his divine life for every human. Jesus always “knew” God (cf. Matthew 11:27). Always and already sustained by the Divine Will as his very own existence for his body and soul, Jesus’ human will could be ‘further’ immersed in the Divine Will through acquired human experience, surrender, and obedience to the Father (cf. Hebrews 5:8; Luke 2:52). His life of human actions and sacrifice opens a share in the life of the Divine Will to all humans.

By the hypostatic union of wills (Jesus’ human will existing through the personal being of the Logos), and Jesus’ lived gift of praise to the Father (in Jesus’ mission of Messiah), the Divine Will further belonged to Jesus’ human will which merited to share the benefits promised in the Divine Will for all humans. In Jesus’ mystery of being fully God and fully man, Jesus instituted the Eucharistic liturgy so he could unite us with his human will and his ultimate one-time sacrifice. By association with Jesus’ humanity and sacrifice in the liturgy (which Jesus instituted), Jesus joins us to the Divine Will—one in being with his human will—and builds [“infuses”] his divine life within our human wills. What began in baptism for Jesus’ disciples is now developed through Holy Communion. There is no longer any barrier or weakness to prevent a human will from abiding in the Divine Will during one’s earthly journey and struggles. Sin and separation from God are overcome in Jesus, the Messiah, by participation in his liturgy, and abiding in his love through the Sacrament that renews us in God’s love.

Jesus’ human will and Divine Will are distinct by nature, but are one within the glorified and risen body of the Logos, where Jesus’ human will draws all life from his infinite and Divine Will. This is what it means to be “seated” at the Father’s right hand. From the moment of the Incarnation, Jesus was always true God and true man. Now, in accessing Jesus’ resurrected life and body in the Eucharist, we are inseparably in communion with and “partakers of his divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4) and seated with Christ (cf. Revelation 3:21). In Jesus’ body, heaven and earth were permanently reconciled and his human will gained the Divine Will for all humans through Jesus’ bodily life, trials, and Resurrection. He is “the eternal life” (1 John 1:2) that became the human entrance for partaking in the divine nature, the bridge to heaven. He is the ultimate and true Temple (cf. Matthew 12:6; John 1:14, Hebrews 10).

Eucharistic Institution

Even before the New Testament was written, Jesus institutionalized that his “eternal life” would be communicated by a new “bread from heaven” (John 6:51). Possessing Jesus’ power to “bind and loose” (Matthew 16:19; 18:18; Revelation 21:14), the apostolic succession (as exercised in the ministerial priesthood) causes transubstantiation of bread into Jesus’ resurrected body and wine into the resurrected blood that is within Jesus’ resurrected, indestructible, and glorified body, “the life-giving Spirit” (1 Corinthians 15:45). Since only God can communicate a “share in the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4)—which is “eternal life”—all Christians implicitly and immediately believed Jesus was God, long before the New Testament writings were finalized and distributed. They believed Jesus is God because that is what every Christian liturgy promoted on the day of Pentecost: “they held steadfastly to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of the bread [cf. 1 Corinthians 11:27; 1 Corinthians 5:7-8] and to the prayers” (Acts 2:42). They believed the bread of the Eucharist communicated eternal life, that it was Jesus’ body, and therefore Jesus is God. The written testimony was secondary to the liturgical testimony of Tradition.

There is a kind of “intertextuality” between the Gospels and Eucharistic liturgies. In their most primitive forms, the Eucharistic liturgies of the Apostles preceded the final written form of the Gospels (cf. Acts 2:42; Luke 1:1). The earliest liturgies proclaimed that Jesus is God (homoousios with the Father) in the very meaning and purpose of Holy Communion. Lex orandi, lex credendi, the law of praying (the meaning of liturgical practice), is the law of believing (and all the implicit doctrines the liturgies presuppose). Since Paul’s letters and the final form of the Gospels, any developments to the prayers of the Eucharistic liturgies and any adjustments to pastoral practices must be in conformity to the Gospels which were written to protect the meaning of the earliest liturgies. After all, Jesus primarily came so that we may “worship the Father in Spirit and in truth” (John 4:23).

For practical application and discernment of future Synods: admittance to the Eucharistic liturgies (cf. Revelation 22:14-15) which are in any way contrary to the New Testament writings (Acts 15:20,29), remains always forbidden in the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. To undermine the New Testament writings is to undermine apostolic succession and its mission to continue worship in Spirit and truth.

Matthew A. Tsakanikas is an associate professor of theology at Christendom College, Front Royal, VA, and editor of catholic460.com; the website where he makes available free manuscripts, videos, and articles. He also publishes on catholic460.substack.com.

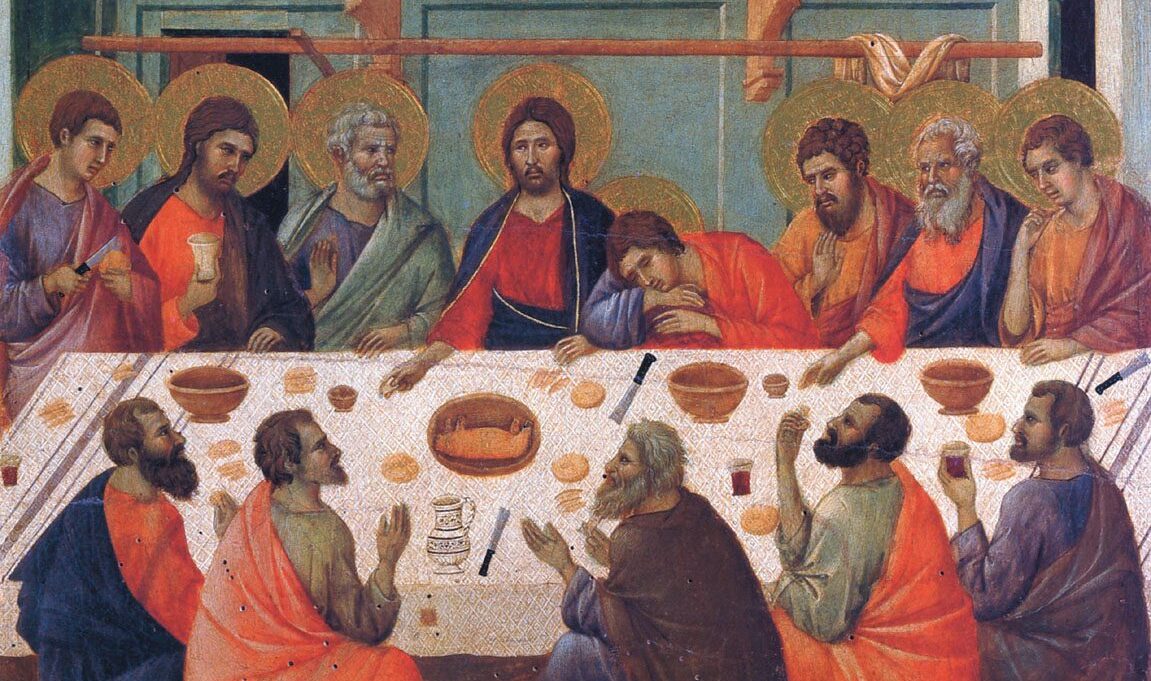

Image Source: AB/Wikiart. The Last Supper (1308-11), by Duccio