Sixty years ago, the Second Vatican Council gave its approbation to the efforts of the preceding Liturgical Movement to restore the liturgy to the center of Catholic piety for all the faithful. The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, set out a vision for both the reform of liturgical rites and for ongoing liturgical renewal in the Church through a series of general principles and practical norms. The 60th anniversary of Sacrosanctum Concilium is an opportune time to examine our liturgical vision and perhaps to adjust our focus.

One of the foremost features of the liturgy that should stand out in great relief is its theocentric character. Sacrosanctum Concilium repeatedly affirms that the sacred liturgy is ordered to the twofold end of the glorification of God and the sanctification of God’s people (see SC 5, 7, 10, 59, 61, 83, 112). At first glance it may seem like these are two rather diverse and perhaps unrelated ends of the liturgy. However, while there is always a priority and preeminence to the divine glory, these can be seen as two interrelated and inseparable ends. St. Irenaeus said in the late second century, “the glory of God is man fully alive; moreover man’s life is the vision of God.” The more perfectly we glorify God, the more we conform to the image of God, and the more we fulfill the purpose for which we were created. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) tells us that “the ultimate purpose of creation is that God who is the creator of all things may at last become ‘all in all,’ thus simultaneously assuring his own glory and our beatitude” (294).

Proper liturgical focus would keep this reality central. In contrast, a distorted vision of the liturgy would involve an anthropocentric turn which views the human person alone as the measure of liturgical praxis. At an extreme, the liturgy would become the community’s celebration of itself, overly concerned with self-expression—and such a view is hardly that of the Second Vatican Council.

While liturgy in the first place glorifies God, this is not merely the God of the philosophers or of pre-Christian monotheism. Christian liturgy worships the God who has revealed himself as a Trinity, one God in three Persons. Here we will focus our vision on the trinitarian character of Christian worship and the work of the Father in the liturgy. Subsequent articles will turn to the action of the incarnate Son and the Holy Spirit in the liturgy.

One of the foremost features of the liturgy that should stand out in great relief is its theocentric character.

The Trinitarian Mystery

The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains that the Trinity is the central mystery of Christian faith and life, and that “it is therefore the source of all the other mysteries of faith, the light that enlightens them” (234). The entire Christian faith is founded on God’s revelation of himself as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, who draws to himself a people to participate in his trinitarian life. Already in the New Testament, which could claim only a nascent trinitarian theology compared to later articulations, the trinitarian pattern of thought and worship is evident, as, for instance, Paul ends his second letter to the Corinthians in this trinitarian key: “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all” (13:14). Likewise, he tells the Ephesians: “be filled with the Spirit, addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with all your heart, always and for everything giving thanks in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ to God the Father” (Ephesians 5:18-20). This trinitarian pattern so thoroughly permeates the thought of Paul that liturgical scholar Cyprian Vagaggini affirms that “the explicit theory and actual practice of St. Paul is that the prayer of Christians, especially their prayer of thanksgiving, is made to the Father through his Son, Jesus Christ, with a consciousness that it is not possible to do this without the active presence in us of the Holy Spirit.”1 The language of the liturgy on this score is the language of St. Paul transposed into the ritual worship of the trinitarian God.

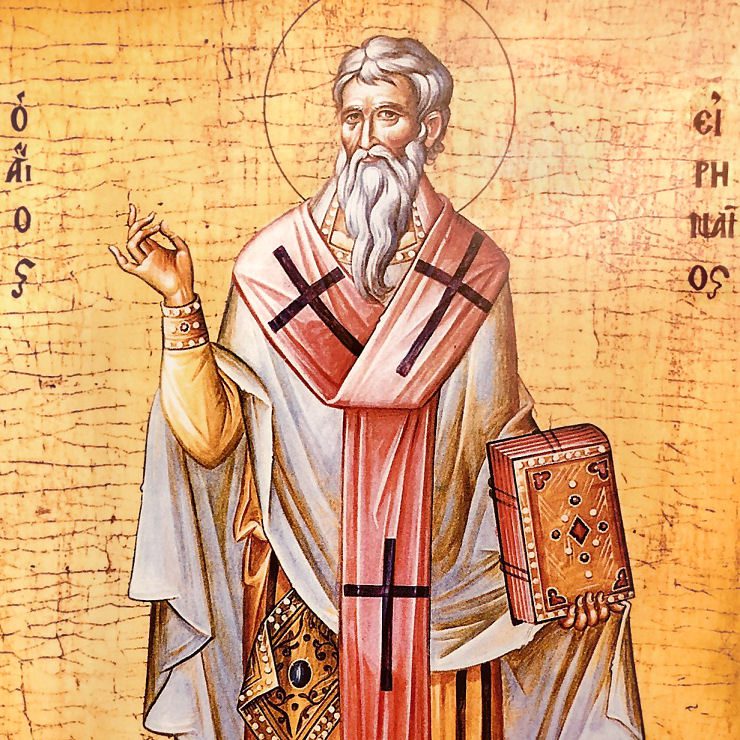

This same trinitarian form is found in the basic shape of salvation history as the dynamic of exitus-reditus. All things come forth from God (exitus) and find their goal in their return to God (reditus) for his glory. This, too, has a trinitarian dimension. All good gifts come from the Father, through his Son, in the Holy Spirit. Gregory of Nyssa illustrates this trinitarian progression: “Whatever operation passes from God to the creature…takes its origin from the Father, is continued by the Son, and is brought to completion in the Holy Spirit.”2 Likewise, the return of all things follows the same path back to the Father. Irenaeus of Lyons writes: “This is the order and the plan for those who are saved…; they advance by these steps: through the Holy Spirit they arrive at the Son and through the Son they rise to the Father.”3 This trinitarian dynamic is not arbitrary or wholly malleable. It is rooted in the eternal processions in the very inner life of God. The Father is the unbegotten source of divinity; the Son proceeds from the Father; and the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son.

A distorted vision of the liturgy would involve an anthropocentric turn which views the human person alone as the measure of liturgical praxis.

Already in the beginning the Father creates through his Word in the presence of the Spirit who hovers over the waters (cf. Genesis 1:1-3; John 1:1-3). And “when the time had fully come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons” (Galatians 4:4-5). The Son sent by the Father becomes incarnate by the Holy Spirit who overshadows Mary (Luke 1:35). Salvation history “is a history which the Father has willed to be as it is, and which He directs infallibly to His own glory…. It is the Father who has delivered up His own Son, Jesus, to the Passion, by reason of the infinite charity with which He has loved us.”4 God creates and acts in history as he is in himself from all eternity, as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The trinitarian economy of salvation has now become the sacramental economy of the liturgy. As God is in his inner life, and as he has worked in creation and in the incarnation, he continues in the trinitarian shape of the liturgy. “In the liturgy of the Church, God the Father is blessed and adored as the source of all the blessings of creation and salvation with which he has blessed us in his Son, in order to give us the Spirit of filial adoption” (CCC, 1110). So central is the work of the Holy Trinity in the liturgy, manifest in its whole structure, that without it the liturgy would be incoherent. The liturgy is an icon of the Trinity. As David Fagerberg says, “the gaze between the Persons of the Trinity, so beautifully depicted by [the icon of] Rublev, depicts the energies glancing from one Person to the next. It is a picture of liturgy: all things come from the Father, and the mission given to the Son and Holy Spirit is to return all things to the Father for his glory.”5 Rather than merely some abstract doctrinal formula, the Trinity is the very life of the liturgy, a life in which we participate.

The Work of the Father

As an action of God ad extra (i.e., in creation, outside the inner life of God), the liturgy is a work common to the divine essence, a joint operation of the three Persons (see CCC, 258). However, we may attribute such actions of the Holy Trinity to one of the divine Persons through what is called appropriation, because that action bears some resemblance to an essential characteristic of that Person. In other words, we appropriate actions to the Father, Son, or Holy Spirit, insofar as those actions bear a resemblance to what that Person “does” in the inner life of the Trinity. For instance, creation is typically appropriated to the Father, not because the Son and Spirit are uninvolved in creation, but because the Father is the font of divinity from whom the Son and Spirit proceed, while himself not originating as proceeding from another Person.

In like manner, when it comes to the liturgy, the Father is named as its source and goal. “The liturgy is inaugurated by the Father, brought into being by the Father, caused to begin by the Father, as all things are. The phenomenon of liturgy is a spiritual instance of creatio ex nihilo.”6 And it is through the liturgy that we return to the Father. The Catechism of the Catholic Church stresses this through the dual aspects of blessing. The entire work of creation and salvation is a blessing from the Father. We, in turn, render blessing to the Father in praise and thanks for this great work. “Blessing is a divine and life-giving action, the source of which is the Father; his blessing is both word and gift. When applied to man, the word ‘blessing’ means adoration and surrender to his Creator in thanksgiving” (CCC, 1078). The liturgy expresses this twofold dynamic as the Church both adores, praises, and thanks the Father, while also continually petitioning the Father for the Holy Spirit and for all our needs (see CCC, 1083; Matthew 7:11; Luke 11:13).

Liturgy is where God invites us to participate in his trinitarian life and elevates us with the grace to do so.

This trinitarian dynamic is visible in the very language and structure of the liturgy’s prayers. The great majority of the collects, for instance, are addressed to the Father and made through the Lord Jesus in the communion of the Spirit. This ancient pattern was so normative, in fact, that the Council of Hippo in 393 declared, “In services at the altar, the collect is always to be directed to the Father.”7 Our Eucharistic Prayers are likewise addressed to the Father in trinitarian form: “You are indeed Holy, O Lord, and all you have created rightly gives you praise, for through your Son our Lord Jesus Christ, by the power and working of the Holy Spirit, you give life to all things and make them holy….”8 In the Eucharistic prayer, as in the liturgy as a whole, the Father is recognized as the source of all good gifts and the ultimate object of prayer and adoration. The Son is the high priest mediating our prayers to the Father. And we ask the Father to send the Spirit upon the gifts on the altar and upon the faithful who partake of the gifts.

Trinitarian Participation

This focus on God the Father in the liturgy means that both the liturgy and all Christian life have a dynamic directionality. The way God has revealed himself to us reflects who he is in his inner life, and so the way we return to God is neither capricious nor left to our determination. The liturgy, following the New Testament, offers us the lens by which we view the world and life in the world as a Christian. This vision provides a concrete path to both understand and live the trinitarian life.

The liturgy is a constant reminder that the doctrine of the Trinity is not merely a theological formula, but a description of the ground of all reality. “The liturgy, if we know how to understand it and live it, is the best means of all for making us penetrate these marvelous realities and for keeping ourselves attuned to them.”9 Made in the image and likeness of the trinitarian God, this means knowing and living as our truest selves.

This, of course, is not simply a matter of self-knowledge. The liturgy is not about self-help, but about God transfiguring us. “The force of liturgy-in-motion does not come from us; it is God’s energy stretching forth and picking us up on its waves. What occurs eternally within the Trinity somehow trespasses its celestial borders to reproduce in us, through sacramental channels, the internal relations of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”10 Liturgy is where God invites us to participate in his trinitarian life and elevates us with the grace to do so.

Moreover, in the liturgy we encounter not just abstract “divinity” or the divine nature, but the Persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in their distinctness without loss of unity. As we are assimilated to the trinitarian life, “there is expression of the special relation which creatures have even with that which the single Persons of the Trinity have in proper respect to each other, or, as theologians would say, with the propria (properties) of the individual Persons.”11 So in the liturgy we encounter the Father who is the source of creation and salvation; we bless the Father in adoration and praise for all his blessings; we ask the Father, through the Son, to impart again his Holy Spirit; and we continue our return to the Father’s house where Christ has prepared a place for us (cf. John 14:2-3). To see the liturgy otherwise is to see only dimly and incompletely—and such a sight is not that of the Church, her Constitutions, or her celebrations.

Footnotes

- Cyprian Vagaggini, Theological Dimensions of the Liturgy (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1976), 202.

- Gregory of Nyssa, Quod non sint tres dii, PG 45, col. 125; quoted in Vagaggini, 205.

- Irenaeus of Lyons, Adversus haereses 5, 36, 2; quoted in Vagaggini, 204.

- Vagaggini, 241-242.

- David Fagerberg, Liturgical Dogmatics: How Catholic Beliefs Flow from Liturgical Prayer (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2021), 29.

- Fagerberg, 35.

- Council of Hippo [393 AD], quoted in Vagaggini, 210. Vagaggini goes on to note: “When the rule was ignored, however, and some orations were addressed directly to Christ or to the Son, these, of course, had of necessity to take on a somewhat different character…. In the Middle Ages a series of new orations was composed, addressed quite clearly to the Son; and from the beginning of the fifteenth century, there are some that begin Domine Iesu Christe. Even further removed from ancient tradition are those medieval orations which are addressed directly to the Trinity. They are, however, relatively few” (Vagaggini, 216-217).

- Eucharistic Prayer III.

- Vagaggini, 246.

- Fagerberg, 33.

- Vagaggini, 201.