Our centuries-old mid-February commemoration of the martyr St. Valentine runs deeper than most people would ever imagine. At root we are celebrating how human love can bear much fruit when it reaches to the heights of Divine Love: for “Unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains just a grain of wheat; but if it dies, it produces much fruit” (John 12:24). As we do with every martyr, we also rejoice in the life of one who has run the course, won the crown, and lived a life faithful to Christ’s exhortations: “If the world hates you, realize that it hated me first” (John 15:18), and “No slave is greater than his master” (John 13:16). Such was the life and death of St. Valentine, whose imitation of Christ through priesthood and martyrdom already teaches us many valuable lessons about true love.

Yet the truth of St. Valentine’s Day is still more profound on account of its place in the calendar. This essentially liturgical memorial follows closely upon the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord, also called the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The two calendar days—the Presentation of the Lord and St. Valentine’s Day—together share roots in late-antique Christian history. Each surprisingly traces its origins to as early as the fourth century.

Our liturgical celebrations in the month of February thus serve as a timely reminder of the blessings that come from fruitful and faithful self-giving love, particularly if and when Christian marriage is modeled on the Paschal Mystery.

Sweet Nothings

In the litany of Catholic holidays that have been adopted, adapted, and consequently distorted by the world, “Valentine’s Day” (as it is now called) remains among the least recognizably Christian of them all. To see how far afield this commercialized festival has gone, one has only to sift through a handful of those saccharine candy hearts and puzzle for a moment over their meaningless messages—text me, ooo la la, xoxo, etc. All it takes is one glance at the senseless sentiments printed on the insides of chocolate wrappers, or in the greeting cards sporting heart-balloons and cartoons, reading—I love you more than any candy heart could say … I love you, Valenwine … I didn’t choose you, my heart did. When we get to the bottom of it all, this multi-million-dollar heap of sweets and sentimentalities, we find little more than a stomachache, a headache, or worse—serious heartache.

While all that we associate with Valentine’s Day might seem fine and innocent enough, young adults and children nonetheless appropriate the conventions of romantic love beginning on Valentine’s Day, particularly through its celebration in schools and in families. Yet we who love and wish to hand on Christian marriage cannot remain complacent with everything the world continues to get wrong about faithful and fruitful married love. For, romantic love is among the most important things to get right in life. So why allow candy hearts and cheap cardboard to say what’s most important for us? Above all on St. Valentine’s Day, why allow the world to continue to whisper its sweet (but empty) nothings about love? It is high time to take back our Catholic feasts: now is the time to reclaim the glory of Christian matrimony and its celebration in February, particularly on the memorial of St. Valentine, priest and martyr.

Roman Holiday

Reclaiming St. Valentine’s Day for Christ begins with understanding the history of this mid-February feast: first the ancient Roman meaning of February itself, then February’s rites and customs, then, finally, the Lupercalia and how all these Roman holidays were first overshadowed and eventually replaced by the Presentation of the Lord and St. Valentine’s Day.

Centuries before Julius Caesar established the Julian Calendar in 45 BC, January and February had been added to the ten-month Roman Calendar by Numa Pompilius (fl. c. 700 BC) to make the year 12 months long. In a fascinating bit of history, the months of the year from Numa’s time until c. 452 BC were arranged with January coming at the beginning of the year and February coming at the year’s end, right before January, like so: January, March, April, May, June, Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, December, February—then back to January.

It is high time to take back our Catholic feasts: now is the time to reclaim the glory of Christian matrimony and its celebration in February, particularly on the memorial of St. Valentine, priest and martyr.

So “Quintilis,” the fifth month of the year on the previous ten-month calendar, would indeed have been the fifth month of the year prior to c. 700 BC, when January and February were not even among the months of the year. Eventually, December would become the 12th month, even though it means “tenth”: after January and February were added, February was moved so that it would come between January and March, thereby pushing December back by two months. Yet from c. 700 BC until c. 452 BC, February remained the last month of the Roman Calendar; and that is why February takes its name from the Latin februa, meaning “expiatory rites” or “offerings for purification.”1 The name “February” thus had primarily liturgical significance in ancient Roman culture.

Now, if you have ever heard of the tradition of throwing a bucket of water out the window on New Year’s Eve, the notion of the februa or purification rites must have been very much along the same lines: out with the old, in with the new. The name of the month signifies the need to start the year with a clean slate, much like our modern-day desire to make—and stick with—New-Year’s resolutions. In a similar way, the Roman expiatory ceremonies were observed at the end of the year, i.e., in the month of February, in order to purge the offenses of the past and secure blessings for the new year ahead.

Closely associated with the februa was the Roman festival known as the Lupercalia, held each year on February 15th. Named for Pan or Faunus under the title Lupercus, the rite itself was held in Rome beginning at the Lupercal, the cave in the Palatine where Romulus and Remus were said to have been fed by the she-wolf. On that day animals were slain in ritual sacrifice, including two goats. Then two young runners donned the animal skins and ran a course while holding in their hands a portion of the blood-soaked animal hides. These skins were called februa. It was the belief of the Romans that the sacrifices, the running of the course, and the striking of women with the animal hides would win from the gods fertility for the fields, for the animals, and for the women who were struck with the februa.2

The Roman rites of expiation, including the Lupercalia, were commonplace in the territories of the Roman Empire even after the Fall of the Empire itself, a fact that is evident in Pope St. Gelasius I moving to suppress the februa and the Lupercalia as late as 494 AD.3

Catholic Answers

Against the backdrop of the Lupercalia and the Roman rites of purification, several things come together in the fourth century to establish and solidify the Catholic answer to the Roman februa.

In the 380s, Egeria of Spain witnesses in Jerusalem the liturgical celebration of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a feast which is also referred to as Candlemas in the Middle Ages and which is observed today as the Feast of the Presentation of the Lord. The many names we give to this day are a sign of its longstanding observance. It is among the oldest of the liturgical feasts on the calendar, and it has thus accumulated a number of associations over the course of 16 centuries. It is rumored to have been spread to the universal Church by Pope St. Gelasius I, the same pontiff who pushed for the eradication of the Lupercalia in 494. Yet, all that can be said for certain is that the Feast of the Presentation is recorded in the oldest surviving liturgical book in the West, the Gelasian Sacramentary (dating to the seventh-eighth c.). There one also finds the memorial of St. Valentine on February 14th.

February takes its name from the Latin februa, meaning “expiatory rites” or “offerings for purification.”

The rationale for the placement of the Feast of the Presentation on February 2nd is simple and logical, yet its ramifications for the Christianization of Roman culture are complex and profound.

Forty days after Christmas, on February 2nd, Joseph is obliged by Mosaic Law to lead Mary and the Christ-child to the Temple for the rites of purification in accordance with Leviticus 12. Because they are poor, Joseph and Mary bring two turtledoves, as they are unable to provide the customary yearling lamb for the burnt offering. Providentially, the place of the yearling lamb is supplied by the Child Jesus in a foreshadowing of the Paschal Mystery.

Coinciding historically with the gradual desuetude of the pagan rites of expiation, the Church thus establishes and begins to normalize the Feast of the Presentation and St. Valentine’s Day throughout the Christian West.

So far, we’ve only examined the roots of Candlemas; but one more piece to the puzzle needs to be placed in order to see how St. Valentine plays a part in this important liturgical time for the Church.

Every year on February 2nd since at least the fourth century, Christians everywhere have celebrated the great mystery of our redemption, the mystery that Christ our Pasch is the only efficacious expiation for our sins (cf. Ephesians 5:2). Every year on this day we meditate on the mystery that Christ the lamb is offered upon the altar of sacrifice for us perpetually in the Mass, that we might persevere and run the race until the end (Hebrews 12:1-2) and afterwards be welcomed to the Wedding Feast of the Lamb with the very words by which the priest invites us to Holy Communion: Behold the Lamb of God, behold him who takes away the sins of the world: Blessed are those who are called to the supper of the Lamb.

The ritual Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary at the beginning of February thus purifies the Roman month of purification itself. The True Son eclipses the idolatrous rites which cannot purify, offering us instead the only rites which can—the rites established by Christ the High Priest, which he has entrusted to his Apostles and their successors so that, through the very same sacramental rites, they might go forth and make disciples of all nations (Matthew 28:19-20).

In the very month formerly dedicated to mere earthly fertility, Christ Jesus—the Fruit of the Womb of the Virgin Mary—draws all Christians into one by baptismal immersion into his mystical body. Standing mystically at the foot of the Cross in sacred liturgy, we call her who is his mother our mother, even as Christ himself exhorts John from the Cross: “Woman, behold, your son … [Son], behold, your mother” (John 19:26-7).

The blessings for which the Roman pagans sacrificed and ran have thus been immeasurably surpassed by the fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham: “I will make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky, and I will give them all these lands, and in your descendants all the nations of the earth will find blessing” (Genesis 26:4).Yet the blessings given to Abraham came only after and because of his great fidelity, as the Book of Genesis goes on to explain: “this because Abraham obeyed me, keeping my mandate, my commandments, my ordinances, and my instructions” (26:5). So, with this liturgical and scriptural focus on fertility—literal and spiritual—laid out before us, we next look to the saint whose life, death, and canonization provide an exclamation point to this liturgical moment in the Church’s year.

St. Valentine

Whatever the historical details of the life of St. Valentine, he is honored for his faithfulness unto death, for being beaten and beheaded on account of his refusal to commit apostasy in response to the menacing threats of Emperor Claudius II, who reigned briefly from AD 268-70.

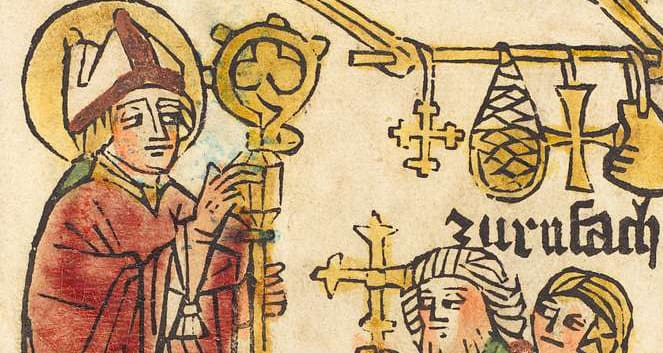

Reading through the numerous vitae of St. Valentine, most of which are disputed in their details but not in their general outline, a portrait of this great saint emerges from a handful of consistent threads. As a priest administering the sacraments during the reign of Emperor Claudius II in the decades before the legalization of Christianity, St. Valentine would have been a natural target for persecution unto death. In his life of ministry, St. Valentine would have possibly presided over Christian marriages;4 and among the reasons why his ministry might have set him at odds with the Roman authorities, his witnessing to Christian marriages seems likely, provided historians are correct in suggesting that marriage would have presented an obstacle to military conscription. Whatever the reason for his incarceration, St. Valentine performed miracles of healing at the behest of the Roman authorities. About the end of his life there can be no doubt: upon refusing to renounce his faith when threatened with capital punishment, St. Valentine gave his life for Christ in martyrdom.

By the year 352, a sepulchral basilica had been built by Pope Julius I in honor of St. Valentine, and from there the cult of St. Valentine began to spread. Signs of devotion to him are found in the many churches bearing his name in late-antique Rome, Sabina, and Latium. An early sign of devotion to him in the universal Church is that St. Valentine appears on his feast day in the oldest surviving liturgical book in the West, the Gelasian Sacramentary (dating to the seventh or eighth c.).

It may appear an accident of history that St. Valentine’s feast day serves as a bookend for the Feast of the Presentation, but, if this is so, it is a happy accident indeed. His reverence for Christian marriage as well as his ultimate witness to the truth of Christ remind us that the saints stand guard over all that has been handed down to us, including, in St. Valentine’s case, the true meaning of Christian love between a man and a woman, sanctified by Christ in the gift of the sacrament of matrimony.

St. Valentine’s Day

The question which remains to us, whether we are parents or teachers or shepherds of any kind, is how best to commemorate the meaning of these feasts of the Presentation of the Lord and St. Valentine’s Day. As St. Paul exhorts the Romans, “Do not be conquered by evil but conquer evil with good” (12:21). It is not enough simply to say “No” to the world’s celebration of the month of February; we must crowd out evil with good.

Whatever our station in life, it is a simple enough task to serve as gate-keepers against any distortion of these days’ meaning. We can begin to keep these days holy by refusing to participate in the commercialization of love. To reclaim the days for Christ, we might read out-loud the narratives associated with the Feast of the Presentation and St. Valentine’s Day, respectively. On a cold winter’s night at home by the fireside, the stories themselves spark their own meditations and conversations. In a school setting, a teacher might read the stories and hold a skit contest, or simply discuss over cookies and punch the histories and legends surrounding these celebrations. If cards there must be, perhaps they might depict scenes from the many legends of St. Valentine. If valentines there must be, perhaps they might depict the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary. For cor ad cor loquitur: heart speaks to heart.

With the history of the Lupercalia and the Presentation ready to hand, we also have a valuable cultural context for the early establishment of these great feasts. We ourselves may fruitfully read with simple enjoyment the many lives of St. Valentine. The vitae Valentini, although disputed in the details of their precise history, nonetheless give testimony to a priest and martyr whose love for Christ Jesus surpassed every instinct of personal wellbeing and self-preservation, even when he was personally threatened by a Roman Emperor. Isn’t this the very nature of true love? For, “In this is love: not that we have loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son as expiation for our sins” (1 John 4:10). That, in sum, is the meaning of The Feast of the Presentation and its Christianization of the month of February. And this, in short, is the response provided to every Christian by the life and death of St. Valentine, priest and martyr: “Beloved, if God so loved us, we also must love one another” (1 John 4:11).

If the exhortation to love one another as Christ has loved us applies to any and every follower of Christ, how much more is this the condition of Christian spouses. We must “live in love” (Ephesians 5:2), never letting “immorality or any impurity or greed even be mentioned” among us (Ephesians 5:3). On St. Valentine’s Day we must dismiss “obscenity or silly or suggestive talk” (Ephesians 5:4) and “not be deceived by empty arguments” about love, for “God is love” (Ephesians 5:6; 1 John 4:8). Christian spouses are called above all to “put on the armor of faith and love” (1 Thessalonians 5:8) and so to imitate St. Valentine in his imitation of Christ (cf. 1 Corinthians 11:1). For in his total gift of self as a martyr, St. Valentine shows us true obedience (cf. Ephesians 5:22) and the total gift of self for the sanctification of the Church (cf. Ephesians 5:25).

St. Valentine, pray for us.

Marcel Brown serves as Head of School at Holy Family Classical School, the Cathedral school of the Diocese of Tulsa and Eastern Oklahoma. His articles and interviews may be found in the Adoremus Bulletin, Crisis Magazine, CNA, Vatican News, The Drew Mariani Show, and The Catholic Man Show. A Knight of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, Dr. Brown was educated at The University of Dallas and The Catholic University of America. He resides in Tulsa, OK, with his wife and their ten children.

Image Source: AB/Picryl

Footnotes

- See februa, in Charlton Lewis, ed., An Elementary Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 319.

- See Lupercalia in Sir Paul Harvey, ed., The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937), 250-51.

- See Lupercalia, 250-1.

- “While over the course of time such liturgical activities did not become an indispensable part of the marriage ceremonies, beginning in the 3rd c. marriages were blessed by the church. Such use is found again in Tertullian, acc. to whom, if two believers marry each other, “the church unites them, the oblation confirms the marriage, the blessing seals it” (Tertull., Ad uxorem 2,8)… Certainly nothing allows us to make generalizations on the basis of what Tertullian wrote in the 2nd and 3rd c., or to assume that such rites were obligatory. Yet the treatment of the marriage of Christians moves in this direction.” Henri Crouzel et al., “Marriage,” Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic; InterVarsity Press, 2014) 692.