I have a keen interest in vestments, and I admit I think about them with some regularity. I enjoy the adventure of finding beautiful, antique vestments, researching fabrics, exploring old liturgical catalogs for embroidery designs, and finding, for example, the pattern for a cassock with the perfect number of pleats. This is all to say, I love vestments.

My own opinion doesn’t really matter, though, and as a priest what really matters is that I am thinking about vestments the way that the Church thinks about vestments. What is really important is that the Church loves vestments, because the way her priests dress at the altar really matters.

Borrowed Robes?

Let’s assume that some among you do, indeed, consider vestments a bit of an afterthought to the nitty-gritty of authentic priestly ministry. There was a time I would have agreed with you. The only problem is, at that time, I wasn’t Catholic.

I was born and raised a free-church Pentecostal and received my first theological lessons from a stubbornly iconoclastic religious community. When we went to church, it was in a converted warehouse because, we thought, only indulgent Catholics would waste resources on a fancy church building. In that warehouse was a stage with a pulpit. Behind the pulpit was a cross with no corpus. In fact, there were no images of Jesus or the saints anywhere in sight because only idolaters have graven images in their worship space. We were encouraged to dress casually, and even the pastor appeared for duties wearing designer jeans and an untucked shirt modeled after the latest fashion trend. After all, only pagan priests wear robes and only legalistic snobs put on a tie to attend church. This seemed right and just to me and I never questioned it.

Until, that is, around the turn of the century when I stumbled into a Holy Sacrifice of the Mass at Holy Family Cathedral in Tulsa, OK. Here, worship was totally foreign to my sensibilities. I encountered prayer via kneeling and signs-of-the-cross. I saw an image of Our Crucified Lord prominently connected with an altar of sacrifice upon which burned candles—totally inefficient, expensive, gratuitous candles. I saw a priest wearing robes and fancy vestments, and altar boys proudly and diligently going about their work in cassock and surplice. I smelled incense. The light that gently spread across my arms was filtered through stained glass. There was decorative painting, carved wood, and statues of saints. The faithful were bathed in beauty, and beauty was the twitch upon the thread that called me home and converted me.

Tailor-made Faith

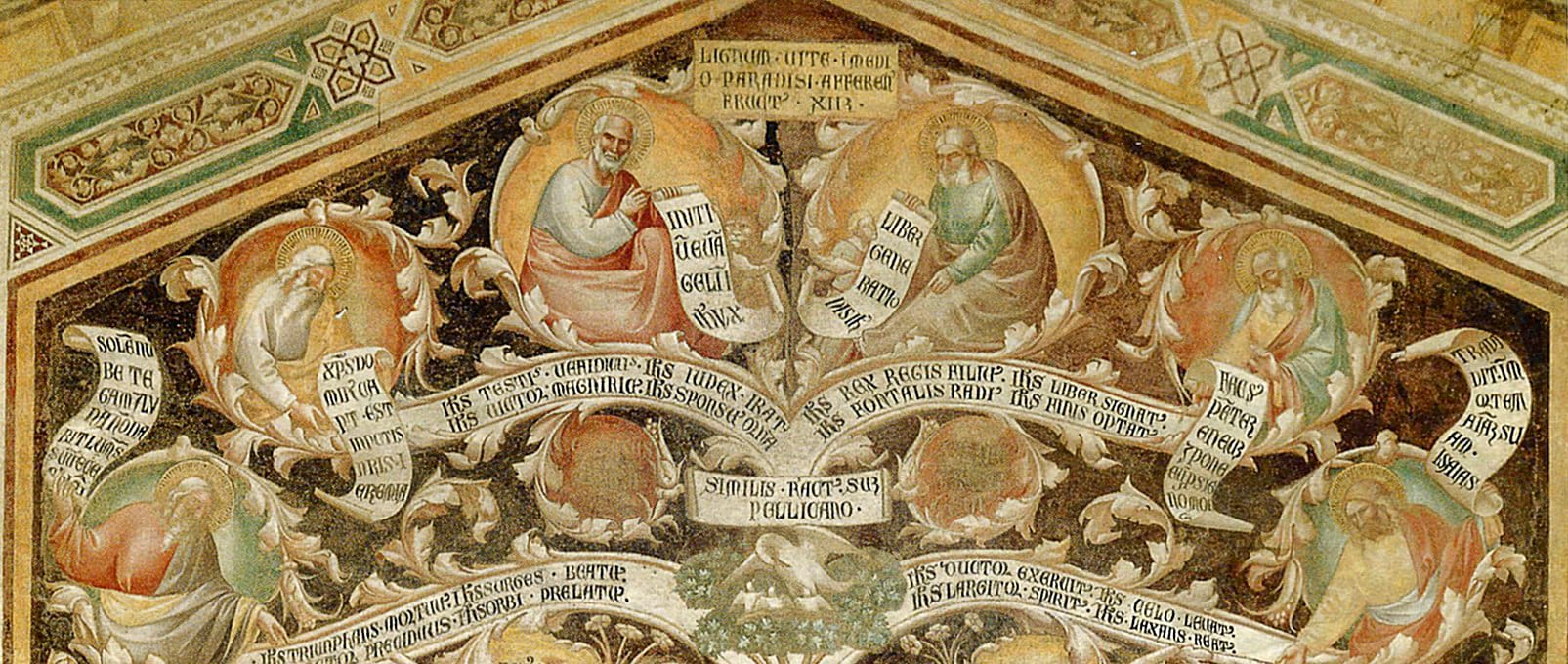

At the time of my conversion, I was living in Tulsa because I was attending a nearby university founded by the famous Pentecostal televangelist, Oral Roberts. It’s funny, I remember walking through the main hall in the classroom building and seeing a model of the Israelite tent of meeting, complete with altar of incense, candles, and gold statues. In class, I studied descriptions and pictures of the way that the high priest dressed in his specific vestments for service in the tabernacle. These vestments looked suspiciously like an alb and chasuble. I also studied St. John’s Apocalypse in Scripture classes and was familiar with the descriptions of heavenly worship which include incense, chanting, white robes, and at the center of it all, a Lamb that had been slain, a true sacrifice. This is the true origin of the Mass. It is a continuation and development of Temple worship, the very same worship that had been commanded by God in excruciating detail.

The Mass is also an anticipation of and participation with the heavenly worship in the throne room of God. Seen in this context, how could anyone consider that vestments are an extra? Here we have the very seed and flowering of worship and devotion—both examples, that which is laid down for us by our ancestors and that which is held out for us as the worship of the Church Triumphant, are replete with beautiful, extravagant vestments.

This isn’t to say that within our tradition all vestments must look identical, or that old vestments are superior to newer designs, or that the Roman style is better than Gothic style. After all, vestments, like anything in the Church, are in a constant process of adaptation or development. Take, for instance, my biretta. The one I wear is the three-horned model with a tuft on the top. The biretta is probably a development from a clerical hood, which over time became detached as a skull cap. The horns may have developed from a need to take the hat on and off during Mass more easily. Children everywhere are in awe of my biretta and ask questions constantly about it after Mass. At first, the wearing of a biretta seems like pure affectation, but the fascination of the children holds the key to unlocking the deeper meaning of vestments—they appeal to the imagination and arouse a sense of wonder.

A child wants to know why the priest wears that hat: and now we’re off and running. The biretta is worn so that it may be taken off. It is an iconographic display by which a servant of the Church, a sacred minister, confronts the grand mystery of how the glory of God paradoxically throws our humble humanity into deep shadow while at the same time raising us up in dignity. To prepare for the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, I dress myself up in the finest head covering to serve as a priest of Almighty God, but at the foot of the altar, a priest is quickly disarmed.

Well-suited Paradox

G.K. Chesterton explores the paradox of liturgical garb in Orthodoxy, writing, “The modern man thought [St. Thomas] Becket’s robes too rich and his meals too poor. But then the modern man was really exceptional in history; no man before ever ate such elaborate dinners in such ugly clothes…. The man who disliked vestments wore a pair of preposterous trousers. And surely if there was any insanity involved in the matter at all it was in the trousers, not in the simply falling robe…. Becket wore a hair shirt under his gold and crimson, and there is much to be said for the combination; for Becket got the benefit of the hair shirt while the people in the street got the benefit of the crimson and gold.” In other words, vestments minimize the personality of the individual man and make him a luminary of the glory of God. It is the law of gift; to the extent we give ourselves away to God in adoration, the more we are clothed in his majesty.

God deserves our gift of beauty, and the faithful are fed by it as with a true spiritual feast. There are many types of vestments that are appropriate, but they all come from the same family tree and share one set of specific virtues—they are beautiful, dignified, and directed solely to the glory of God. When wearing them, the priest as individual recedes and the office of the priesthood comes to the fore. As that other great convert-turned-apologist of the early 20th century Ronald Knox says, a priest must not forget that he is only a priest of the universal Church. There is beauty in being thus chastened, and my vestments remind me daily that the Church does not particularly need me for her survival.

In exchange, a priest receives a greater gift, which is participation in the priestly ministry of Our Lord. For this reason, a priest must be glorious and he must be set apart. Nikolaus Gihr, in his book The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, writes about a High Priest of the Old Covenant named Simon: “And as the sun in his glory, so did he shine in the temple of God…when he went up to the holy altar, he honored the vesture of holiness” (Ecclesiasticus 50:6,12). Gihr comments, “Now, if God even in the Old Law…prescribed such beautiful, such rich garments for the liturgical functions…, how much more is it the Lord’s will, that His beloved Spouse should appear at the altar robed in magnificence and splendor, whenever she celebrates that adorable Sacrifice and spreads the Table of the Lord.” He goes on, “To the believing eye and mind it would appear as a desecration…to attempt to offer the Holy Sacrifice at the altar in the ordinary everyday dress.”

This point is extremely important. As an individual, sinful man, I have absolutely no place at the altar. My merits have not gained me the ministry. Because the soul and body are inextricably interweaved, and the language of our bodies expresses the disposition of the soul, it would be a highly contradictory statement for me to go up to the altar wearing my own, ordinary clothes. To do so would be to proclaim that I am fit to do so, just as I am. Nothing could be more presumptuous or wrong-headed.

A Weave of Wills

Ronald Knox once wrote a book for schoolgirls called The Mass in Slow Motion. In it, he proposes a thought experiment while the priest quietly prays his “Judica me Deus/Judge me, O God” at the foot of the altar. Imagine, he writes, that you are appearing before a royal court but have no special clothes, “that would put a lid on your misery, wouldn’t it? And that is how a priest feels or ought to feel when he goes to the altar.” Spiritually speaking, in the depths of his sinful heart he is unclothed, so he absolutely must step into the sacerdotal office of the priesthood and allow God’s mercy to clothe and usher him over the threshold to the altar of sacrifice.

Because of this, vestments even in all their variety follow a similar pattern, and a Catholic priest at prayer is generally recognizable as an “icon of Christ the priest” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1087). What is a priest required to wear at Mass? What is the minimum? I’m not an expert in ecclesiastical law, but according to the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, at least an alb, stole, cincture, and chasuble are necessary for a priest in the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.

But to ask our question in terms of minimum requirements is precisely the wrong way to think about vestments. It won’t do to assume that simply because a priest technically has the right garments on that it doesn’t matter if they are high quality or low, beautiful or ugly. After all, the goal of our worship is not to do the least amount possible, and it isn’t to be efficient. The Mass is playfully—almost unnecessarily—beautiful. It operates by its own inner logic and creates its own mystical meaning.

Remember, in the service of God nothing is merely exterior, all is figurative of the interior. Which is to say, vestments can preach a homily all on their own with no words. Beauty at Mass is a reflection of the beauty of God. The unspoken homily goes even deeper, too. We’ve already alluded to it several times in this essay—God deserves glory, his glory shines through sensible things, and the human body is being redeemed. In The Spirit of the Liturgy, Pope Benedict XVI marks the transition from clothing to the body itself, writing of St. Paul, “The Apostle does not want to discard his body, he does not want to be bodiless…. He does not want flight but transformation. He hopes for resurrection. Thus the theology of clothing becomes a theology of the body. The body is more than an external dressing up of man—it is part of his very being, of his essential constitution.”

God’s Golden Thread

Do some priests [slowly points finger at self] dive too deeply into the minutia of vestments? Maybe. I’m sure we can all find a prudential line wherein humility crosses over to pride, but it is helpful to recall that sacred vestments that are put into the service of the Church are, by their very definition, a source of humility for a priest. They are the living embodiment of the wish, “He become greater and I become lesser.” In that wish is the desire to love and serve our Creator the best we possibly can. Vestments are part of priestly ministry, not an afterthought. Beauty converts hearts and souls—I am living proof of that.

If we make a gift of beauty to others through the beauty of sacred worship, we will recognize in priestly vestments an echo of the primordial beauty of God, faithfully witnessed to by the generations of priests, an echo that reverberates and pulls us into the future, drawing our eyes directly to the source of all beauty, the one who spoke creation into existence, Our Lord and Savior seated upon his throne.