English humorist P.G. Wodehouse (d.1975) has authored a number of the English language’s funniest books, among them, Right Ho, Jeeves (1934). At one point in this narrative, the story’s main character, perennial bachelor Bertie Wooster tries to rekindle the dead sentiments of love in his cousin Angela toward her former fiancé, Tuppy Glossop. Wooster’s strategy is to “roast” Glossop to Angela, in hopes that she will—“like a mother tigress”—come to his defense, thus renewing lost love. Bertie begins the disjunctive dialogue with his cousin by recalling his childhood friend’s vulgar manners during their schooldays:

“‘Uncouth’ about sums it up. I doubt if I’ve ever seen an uncouther kid than this Glossop. Ask anyone who knew him in those days to describe him in a word, and the word they will use is ‘uncouth’. And he’s just the same today. It’s the old story. The boy is the father of the man.”

She appeared not to have heard.

“The boy,” I repeated, not wishing her to miss that one, “is the father of the man.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I’m talking about this Glossop.”

“I thought you said something about somebody’s father.”

“I said the boy was the father of the man.”

“What boy?”

“The boy Glossop.”

“He hasn’t got a father.”

“I never said he had. I said he was the father of the boy—or, rather, of the man.”

“What man?”

I saw that the conversation had reached a point where, unless care was taken, we should be muddled.

“The point I am trying to make,” I said, “is that the boy Glossop is the father of the man Glossop. In other words, each loathsome fault and blemish that led the boy Glossop to be frowned upon by his fellows is present in the man Glossop, and causes him—I am speaking now of the man Glossop—to be a hissing and a byword….”

Now, if you will permit a quick shift from the mundane to the sublime, I was reminded of Wooster’s convoluted “the boy is the father of the man” speech to his cousin when coming across the following passage from St. Gregory of Nyssa (who apparently anticipates P.G. Wodehouse). Commenting on Ecclesiastes’s meditation on all things in due season (“a time to be born, and a time to die,” etc.), St. Gregory says:

“It seems to me that the birth referred to here is our salvation, as is suggested by the prophet Isaiah. This reaches its full term and is not stillborn when, having been conceived by the fear of God, the soul’s own birth pangs bring it to the light of day. We are in a sense our own parents, and we give birth to ourselves by our own free choice of what is good. [My emphasis] Such a choice becomes possible for us when we have received God into ourselves and have become children of God, children of the Most High. On the other hand, if what the Apostle calls the form of Christ has not been produced in us, we abort ourselves. The man of God must reach maturity” (Office of Readings, Tuesday of the 7th Week in Ordinary Time).

St. Gregory uses striking language and addresses many current aspects of our sad state. The Church father says that we “abort ourselves” by not conforming ourselves to Christ. Recent pro-abortion legislation in New York and Virginia reveals that St. Gregory’s words have for citizens of the United States a tragic, literal, and obvious reality. Will we parents abort ourselves—our country—out of existence? Moral turpitude and spiritual turpitude are two sides of the same coin, after all.

But of course St. Gregory is speaking here principally of spiritual parentage, birth, and maturity. “We are in a sense our own parents,” he writes, “and we give birth to ourselves by our own free choice of what is good.” Liturgically speaking, in today’s ritual celebrations, what are we giving life to? We must bear in mind, of course, that the Trinity and the Church are the liturgy’s principal agents of bringing that life into existence. Nonetheless, how are we as celebrants and participants in the liturgy cooperating with the grace that allows us to bring forth our spiritual birth in Christ? Is the Church’s liturgical life abundant and vibrant? Or is it dying and anemic?

Every individual, of course, can answer this about himself. But collectively, how do we respond? Pew Surveys and pew counts, while not the only indicators, offer some sobering answers. A recent Pew survey indicates that less than 36 percent of adults attend church services in the U.S., and news for Catholics in that same study is not much better—reporting that only a dismal 39 percent of Catholics attend Mass once a week.

Such numbers add up to a lack of concern for our spiritual maturity. How do we, who are “our own parents,” foster not “stillborn” celebrations but long-lasting liturgical life? St. Gregory’s chilling words are worth repeating: “[I]f what the Apostle calls the form of Christ has not been produced in us, we abort ourselves. The man of God must reach maturity.” But Catholics have within their grasp the means to rescue the precious gift of faith. The Church’s liturgy manifests “the form of Christ” to all who participate—or at least it is supposed to. If it does not, the fault lies not with the inherent efficacy of the liturgy, but with the ministers and participants and how they celebrate it.

In his 1988 Apostolic Letter Vicesimus Quintus Annus (VQA), John Paul II reflected on the quarter of a century which had passed since the Second Vatican Council promulgated its reforms. The late pontiff notes that the efforts of the post-conciliar Church “have been directed towards ‘bringing to maturity in the sense of movement and of life the fruitful seeds which the Fathers of the Ecumenical Council, nourished by the word of God, cast upon the good soil (cf. Mt 13:8, 23), that is, their authoritative teaching and pastoral decisions’” (VQA, 3; my emphasis). As 25 years has grown into 60 years, does the liturgy continue to mature—and mature us in the faith? Or is it, and its celebrants, stuck in rebellious adolescence, rejecting its lineage?

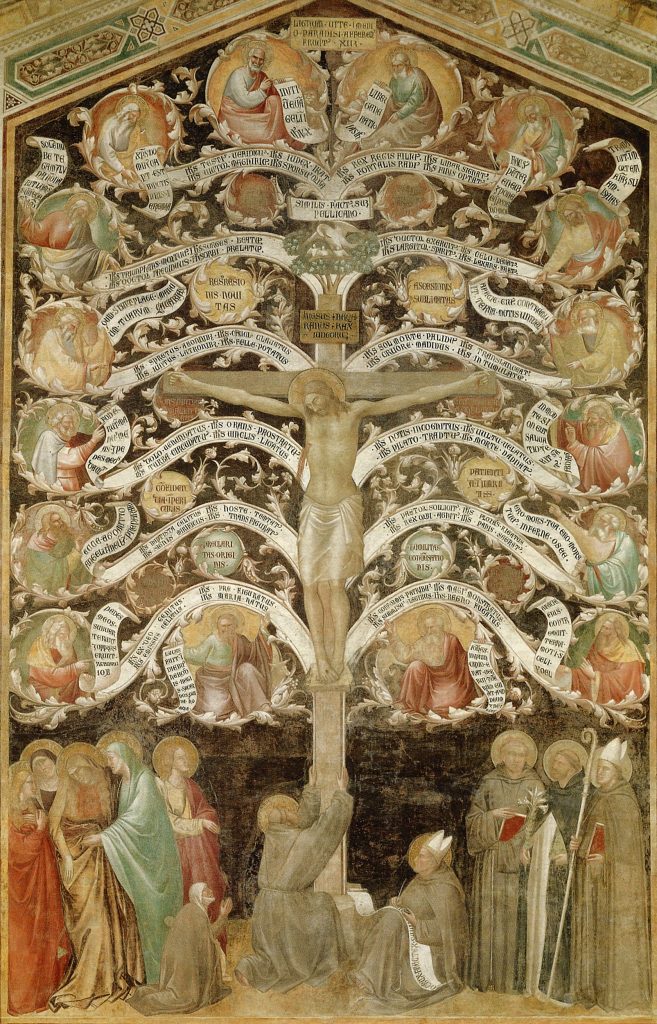

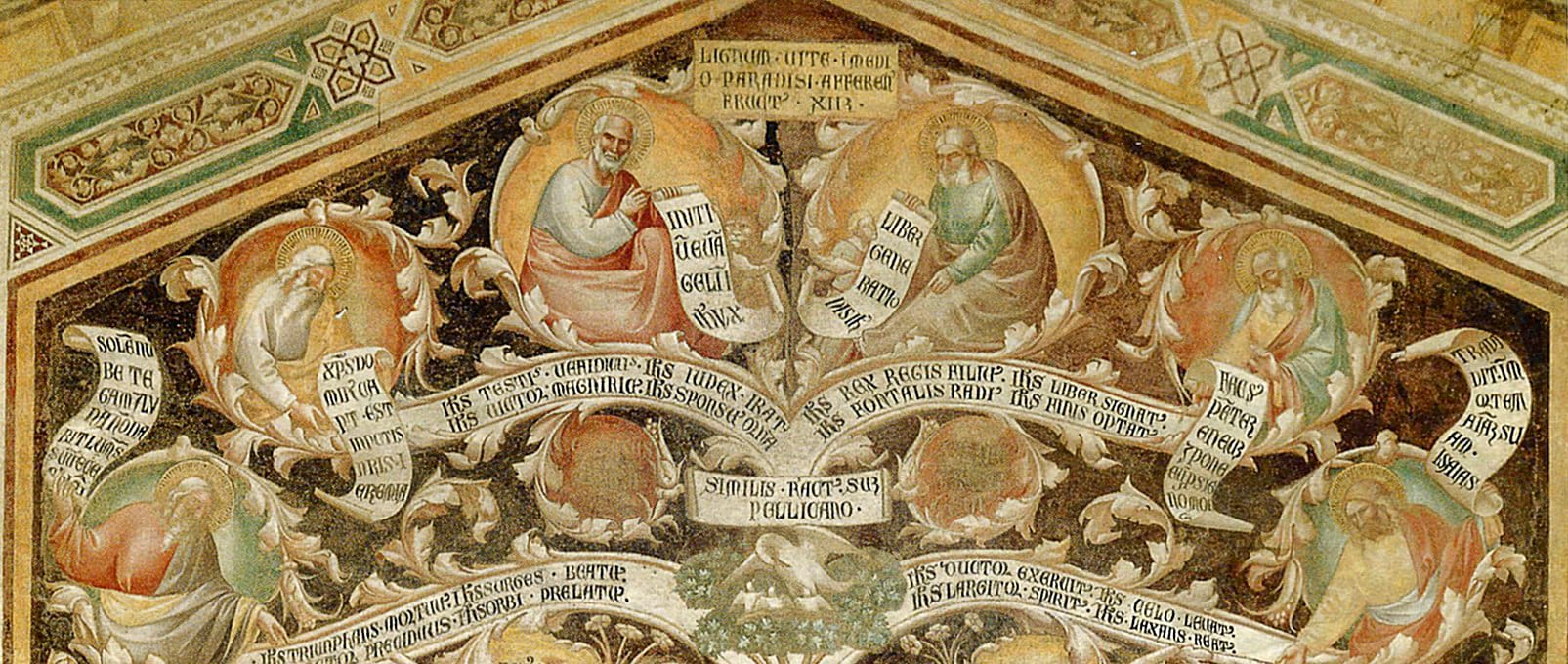

The Holy Father concluded his 1988 letter with some insights for us “parents” of our own faith. “The seed was sown; it has known the rigors of winter, but the seed has sprouted, and become a tree. It is a matter of the organic growth of a tree becoming ever stronger the deeper it sinks its roots into the soil of tradition” (23). May today’s liturgies bear tomorrow’s fruit—allowing us and our flesh-and-blood children to become saints—by organic growth rooted deeply and strongly in tradition. Let us not, like Tuppy Glossop, become “a hissing and a byword.”