While there are relatively few Catholics who could name a single book on the liturgy, there are even fewer who could name one on liturgical vestments. Lack of familiarity with The Incredible Catholic Mass by Venerable Martin von Cochem or The Spirit of the Liturgy by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger is a shame. However, the inability to name a book on liturgical vestments is quite understandable—especially since there are very few in print.

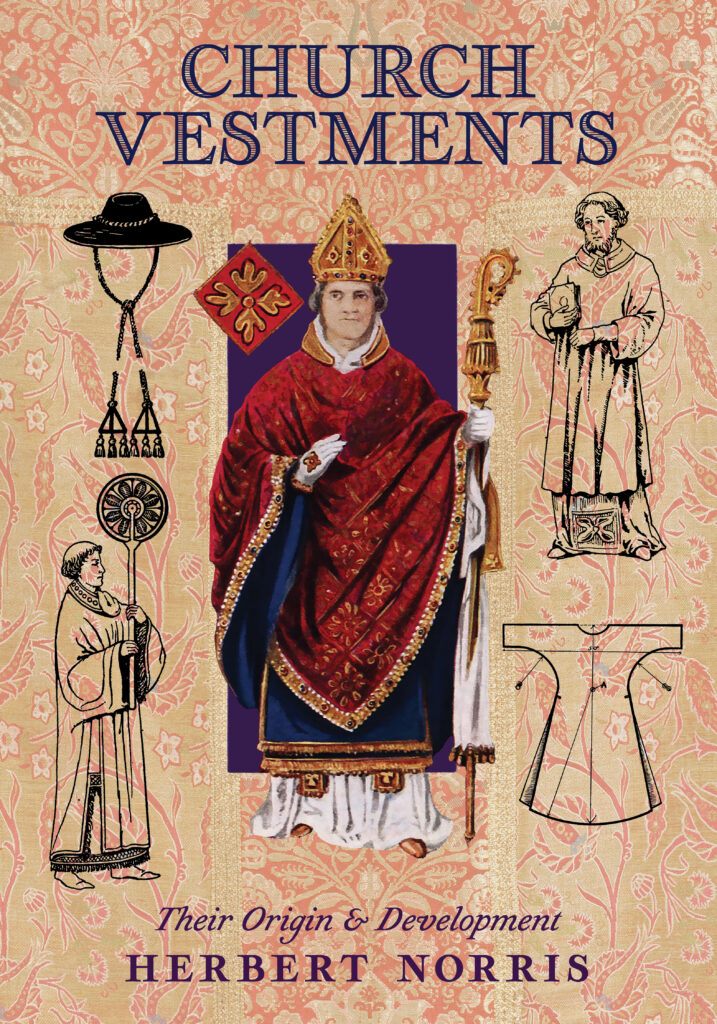

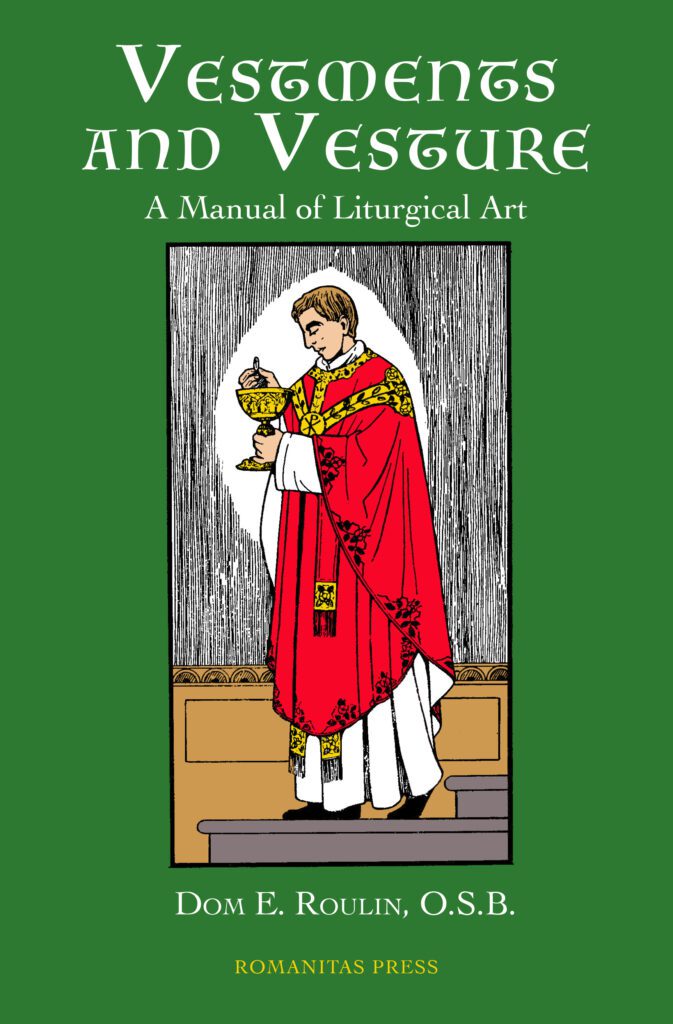

Late last year, however, two books were brought back to print to help address the scanty supply of such works. In October 2023, Angelico Press reprinted Church Vestments: Their Origin and Development by Herbert Norris while Romanitas Press found it fitting to resurrect in November 2023, the 1950 classic Vestments and Vesture: A Manual of Liturgical Art by Dom E. Roulin. This work was first published in French as Linges, Insignes, and Vêtements Liturgiques in 1930.

Liturgical Threads

Originally published in 1949, Norris’s work is a general survey of albs, chasubles, stoles, copes, and every other major piece of clothing that could be found on a cleric from the beginning of the Church to 1500. There are some threads in this book that will probably surprise readers. For example, Norris explains that the use of colors specific to liturgical seasons was not common during the first eight centuries of the Church. Apparently, a Catholic living in 500 A.D. could attend an Advent Mass with a priest wearing gold or green just as easily as he could with a priest wearing purple or red.

By 1198, Pope Innocent III stated that white was for high festivals such as Christmas and Easter; green was for weekdays without feasts; red was for feasts of apostles and martyrs; black was for Advent and Lent. There was a dispute about this latter color; some places used red, while others used black, which might be why we now have a happy medium between the two—purple—for Lent and Advent.

One of the most outstanding features of Norris’s book is a large section on clerical headgear. From classical Greek to classical Roman to Roman Catholic, the historical heritage and development of a bishop’s miter is outlined. Various forms, such as headbands, caps and tiaras—including the “triple crown” (long before it became popular parlance in the sporting world), are described and drawn.

When headgear became less common among laymen in the Roman Empire, it was still retained within the Church. This is a common theme for all aspects of clerical dress: the Church preserves what the world jettisons. Norris explains this principle in a general outline preceding chapters on specific aspects of clothing: “When the classical Roman dress began to be superseded by the barbarian type, the conservativeness of religion asserted itself by retaining these old-fashioned garments for the minister after laymen had abandoned them: and in consequence the celebrant at the Eucharist came to wear clothes which were no longer in secular use. So it came about that the ordinary civil costume of the well-dressed layman of the first century A.D. acquired sacerdotal significance as an ecclesiastical vestment. That this happened over and over [with different garments] will be evident from the following pages.”

Seamless Transition

Roulin’s book is more expansive and detailed than Norris’s, covering the underpinnings of vestments from the early Church through the early 20th century—and also addressing banners, altar linens, tabernacle veils, and canopies. Not only is an objective historical sketch offered, but so is subjective analysis of what makes for good vestments and what does not.

The scope of these two books can be compared with an alb and a chasuble. The alb is a plain, white garment symbolic of baptism—the foundational sacrament and entrée for the other six; the chasuble is a more specific garment with several color possibilities and countless design possibilities, all reflective of the priesthood. So in its likeness to the simple alb, Norris’s book covers all the vestment basics, while like the more complex chasuble, Roulin’s text ventures into vestment specialties and beyond.

Readers may be surprised by Roulin’s belief that symbols on vestments (which are, after all, themselves symbolic) are not required for liturgical outfitting. He states, “The primary aim in the designing and making of a vestment should be the production of a thing of beauty, and this can be done without the use of symbols. Simplicity, proportion and cleanness of line will produce an immediate and forcible impression of beauty.”

Roulin thought that properly-fitting fabric flowing in straight lines offered enough for liturgical propriety. The author is especially critical of trivialities such as white embroidery on white fabric, which is nearly impossible to detect—let alone appreciate for its symbolic value.

However, when more symbols were used upon the already symbolic liturgical vestments, he had a certain rule of thumb: They should be obvious in meaning to the faithful and not too detailed. After all, only a few people will be in a position to see the details; most viewers will be several yards away from the priest during Mass, so a cross, lamb, dove or fish should be presented on vestments in order to be easily visible from such a distance.

Although the “fiddleback” chasuble had gained popularity by his day, Roulin did not appreciate these shortened chasubles commonly referred to as “Roman.” He references Father Adrian Fortescue’s declaration that they should not be so named. These chasubles came into vogue in the 17th and 18th centuries, yet they acquired the name “Roman” (even though they were not a specialty of that area) rather than “Baroque” (the era in which they were born and raised). Somehow, selective geography overrode simple chronology.

Nomenclature aside, whether readers share Roulin’s chasuble preferences or are more inclined to the “efficient” ones that look like body armor or a shield (fitting for a cleric in the Church Militant), they will find many things to think about. Readers will likely be greeted by several new words: brocade, damask, casula, orphrey, rochet, buskin and galloon among them.

Veiled Revelations

Anyone with a vested interest in learning more about the history, philosophy, and aesthetics of Catholic clerical clothing will find a veritable trunk show in Vestments and Vesture: A Manual of Liturgical Art, as well as Church Vestments: Their Origin and Development. However, certain groups may gravitate more to them—including bishops, priests, deacons, seminarians, liturgical clothing designers, as well as interior church designers and architects. After all, those who design and decorate houses of worship do need to consider what their sanctuaries will look like when filled with ministers, as well as how those ministers can perform their sacramental functions with ease.

Sacred architecture is, after all, an incarnational endeavor. It started with the Son of God becoming man and continues with men aspiring to unity with God. The Lord has taken our human needs into consideration, so a church architect should as well. Our humanity is not obliterated by God; but methodically redeemed, ennobled, and ultimately glorified.

Roulin himself was an architect and two images of sanctuaries he designed are included in the book. These images and two chapters (XI and XII) extoll the virtues of altar coverings (whether deemed a “ciborium,” “baldachin,” “freestanding dome” or “canopy”) and complete tabernacle veils.

Why would the Church require that tabernacles be completely covered with a veil? Roulin writes of how, even more than a sanctuary lamp, a complete tabernacle veil indicates something (or Someone) special and uncommon within. Not to mention, fabric is used to clothe persons—whether directly on their bodies or for their furnishings.

Trends in Taste on the Mend

While Roulin’s book is a serious study of the principles involved in liturgical vestments, he does offer some critical commentary on some ill-advised choices in style. He was not one to offer false praise, so some needling—albeit principled—of bad taste can be found. For, while Roulin was clothes-minded, he was not close-minded. He stated that there are some boundaries when it comes to liturgical vestments and vesture, but there is a very wide range for variation within those boundaries.

Indeed, Roulin was in favor of whatever style looked appropriate for the highest function a man can perform, whether “Roman,” “Gothic,” “Baroque,” or a creative combination thereof. He was in favor of true works of art whose impact would endure, rather than trendy designs that would pass quickly.

What was deemed “trendy” for the laity to wear was confronted by Colleen Hamond’s Dressing with Dignity two decades ago. With the reprinting of Church Vestments: Their Origin and Development and Vestments and Vesture: A Manual of Liturgical Art, the Church now has a better opportunity to grasp how ministers have been—and could be—dressing. Indeed, we have regained resources for better glorifying Almighty God. Psalm 96 exhorts believers to “worship the Lord in holy attire,” so Norris and Roulin will help those who, to that goal, aspire.