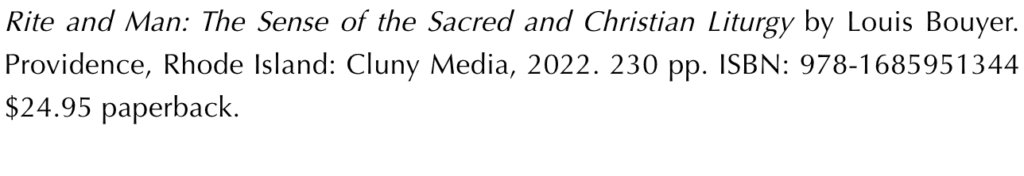

In Rite and Man: The Sense of the Sacred and Christian Theology, newly republished by Cluny Media, Louis Bouyer shows how the Incarnation is at the heart of the liturgy. Bouyer, a noted theologian who is considered to be one of the major architects of the Second Vatican Council, begins by noting two differing views regarding the liturgy. He likens them to early Christological heresies. The first view on the liturgy he identifies with the Monophysites. He says that this view considers the liturgy as something completely divine and that it should “somehow escape humanity.” The heresy of Monophysitism essentially states that Jesus had only one divine nature. This, of course, is false since Jesus is one Person but has two natures: one divine and one human. Such a view of the liturgy is easily discredited when one observes that a priest (a man) is necessary for the celebration of the liturgy which cannot, therefore, be something purely divine.

The second view Bouyer likens to Nestorianism. The heresy of Nestorianism states that there are two separate persons in Christ: one divine and one human. He says that this view of the liturgy overemphasizes its human aspects to the point where the divine is at risk of fading away from it. Again, this view is easily discreditable since Catholics believe that when the priest consecrates the bread and wine they become the Body and Blood of Christ Who is God.

Bouyer’s solution to resolving this tension between a wholly abstract and wholly earthly liturgy is to propose an Incarnational view. As Bouyer sees it, the liturgy—like the incarnate Christ—is something that is both divine and human at the same time. Bouyer’s study then examines these aspects of the human and the divine for, as he writes, “It is by a more profound discovery of himself that man is able to discover, as in an impress, the divine visage and presence. Or perhaps it would be better to say, it is only by discovering God coming to him that man solves the puzzle of his own existence” (3). From here, Bouyer goes on a journey examining various aspects of comparative religions and primitive religions as well as using depth psychology in order to provide readers a better grasp of Christian rituals.

At the outset of Bouyer’s book, he notes the necessary relationship between actions (or rites) and words in religions: “Sacred words and sacred actions are as a matter of fact always found joined together” (56). Still, for Bouyer, sacred words must have a priority over sacred actions. Logically, this makes sense since actions flow from words, as is clearly seen in the sacraments. Without the form (words such as “I Baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit”), the matter (water) would have no meaning.

Bouyer warns that the liturgy in the past has sometimes been seen as something entirely incomprehensible—“something at which the people assisted but in which they had no part…” (61). To overcome this barrier, Bouyer insists on a rediscovery of the true meaning of the sacred words in order to better understand and enter into the sacred actions or rituals: “The remedy must be sought…in a rediscovery of the original meaning and nature of the words and rites so that they are no longer blindly opposed to each other” (64).

Another issue raised by Bouyer is that of the nature of sacrifice. Bouyer argues that the usual explanation for the translation of the Latin sacrum facere as “to make holy” is not the true essence of a sacrifice. More than a “making,” sacrifice is a “doing.” He states that for the ancients, sacrifice was an act—specifically a sacred meal. For Bouyer, the full meaning of this view of sacrifice comes with Christianity: “In antiquity, the Eucharist was seen as the sacrifice of the Christians because it was the sacred meal of the Christian community” (86).

Pagan Mysteries and Christianity

One of the major topics that Bouyer treats in his exploration of pre-Christian rites is the “Mystery Religions” as compared to the Christian sacraments and rituals. He begins by discussing a number of these religions and their practices (such as that of Persephone and her mother, Demeter). His conclusion on the topic is that Christianity was not influenced by these Mystery Religions but was rather influenced by Judaism because “the seed of anything essential in Christianity certainly cannot be found in [the mystery religions]. If we look for the sources of whatever resemblances there may be between Hermitism or Neo-Platonism and Christianity, they should be attributed to their common Jewish background, whenever directly Christian influences must be ruled out” (141).

Also in contrast to the Christian rites, Mystery Religions tried to keep their rituals secret, similar to Gnostic practices—as if they had some secret knowledge or wisdom to impart to their adherents. Bouyer points out that the Christian mystery “is a fact, an historical event, in which human history reaches its summit. It is a unique fact in which God Himself takes that history back into His hands while He Himself descends into it” (144)—and this design is no secret! Here again, the Incarnation is at the heart of the Christian mystery—at the heart of the Christian rites and liturgy. The Christian mystery is essentially that of the Incarnation: Jesus Christ. For Bouyer, the Christian mystery will “find in its turn a ritual expression. It will take up again and recast the ancient material of the natural rites that Judaism had already purified and transfigured. It will do this by bringing to fulfillment their ‘historization.’ It means that their primitive, cosmic meaning will have been absorbed into the final meaning of sacred history” (151).

Sacred Orientation

In Rite and Man, Bouyer then turns to discussing what he calls “Sacred Space,” beginning with early religious practices and then leading into Jewish and Christian uses. According to Bouyer, sacred space includes many dimensions, among them shape, orientation, location, etc. The author points to the Temple in Jerusalem, which is considered holy because of its location—Jerusalem is the city of David, God’s servant, which in turn is located in the Promised Land given to the Israelites. (In similar ways, Mecca and Medina are considered holy places by Islam specifically because of their location.) As for the importance of shape in sacred space, Bouyer notes that Church buildings with domes (tholos) signify devotion to a particular saint whereas rectangular ones are primarily places of worship similar to the Jerusalem Temple. There is a great variation and significance when it comes to churches and their architecture, but each points ultimately to the same vitality reserved for sacred space.

How, though, does orientation play a role in sacred space? Bouyer spends a good deal of time on this dimension, noting that Jewish synagogues were built in such a way that the rabbis and the people all face Jerusalem where the Temple was located. From here, the author then discusses a similar Christian orientation of sacred space as integral to liturgical celebrations. During Christian liturgies, the priests and people do not face Jerusalem. Rather, together, they faced toward the East (ad orientem): “The Christian church, like the Jewish synagogue, is carefully oriented. But it is no longer directed toward Jerusalem but toward the geographical east. This is so true that contrary to the synagogues, Christian churches to the east of the Holy City did not hesitate to turn their backs on it” (175).

Again, Bouyer explains the great significance and importance of this orientation by noting that Christians “had definitely substituted for the earthly Jerusalem the heavenly Jerusalem that is our mother, of which the Apostle speaks. And they were waiting to see it descend from heaven with Christ in His Parousia, which had become symbolized for them by the East, in accordance with the Gospel formulas” (175-176). The orientation of the Christians was no longer focused on this passing life but now had an eschatological dimension. It is an anticipation of the Second Coming of Christ.

The altar too, Bouyer says, should be properly oriented within sacred space. The idea that it should be facing the people (versus populum) is actually a misunderstanding. He offers a detailed look into this subject and concludes that “the notion that the arrangement of the Roman basilica is ideal for a Christian church because it enables priests and faithful to face each other during the celebration of Mass is really a misconstruction. It is certainly the last thing which the early Christians would have considered, and is actually contrary to the way in which the sacred functions were carried out in connection with this arrangement” (180-181).

Sacred Time

Another topic Bouyer addresses in his book is that of sacred time. For the ancient and pagan religions, the gods were seen as being above and unaffected by time, whereas man is born, lives, and dies within time and is subject to it. For this reason, there was a great divide between man and the gods. With Judaism, however, something different happens. God freely intervenes within time and yet is not bound by it. Because of this divine intervention, time takes on a new meaning. History is not merely history—it becomes sacred history or Salvation History. In fact, the Scriptures, which are the authoritative chronicle of Sacred History, record God’s continuing intervention in time. For Bouyer, one of the most important parts of Salvation History is the Pasch of Israel which, he writes, “was the eternal reminder of a decisive act of God through which He had once and for all taken in hand the cause of His people” (204). The greatest event in this history is the Incarnation, the Passion, Death, Resurrection, and Ascension of Jesus Christ. The God of the Jews and Christians is no longer distant but close and personal.

Three Takeaways

In his conclusion, Bouyer states that he hopes his book will highlight three major concepts for the Liturgical Movement. The first is to stress the importance of the word in worship. Bouyer states that the word and worship must go hand in hand and must not be separated: “No Christian event or Christian rite can become an object of faith independently of the divine Word which gives it meaning” (219). Bouyer notes the sacramental connection between word and worship as well: sacraments are composed of matter and form (words)—both are necessary for, without one or the other, there is no sacrament.

The second concept Bouyer hopes to impart through his book is regarding adaptations in the liturgy. Bouyer warns against two extremes when it comes to adaptations. The first is rationalism which Bouyer says “is the temptation that must be resisted in the adaptation of the liturgy to our contemporaries. Such an approach would readily dissolve whatever is mysterious under the pretext of explaining it…” (224). As for the second extreme, Bouyer warns that “one must guard against the temptation of absorbing the originality of the Christian mystery into pre-Christian mythologies” (224): while assuming many of man’s natural, ritual antecedents, Christianity remains unique and cannot be reduced to its precursors.

The final concept Bouyer hopes the Liturgical Movement embraces by reading his book is the proper place of Christian worship—i.e., the church building. Here again, Bouyer reiterates the proper orientation of the church and the assembly. He states that the whole point of this orientation is not about people but about God: “It is rather a divine gathering, where the divine Word invites us to proceed together toward the Eucharistic banquet, which in turn has no end itself, but should orientate us towards the final uprooting of the parousia” (227).

Rite and Man was originally published the same year as the Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, and is an invaluable resource for liturgical theology. It provides a good introduction to Bouyer, one of the great thinkers of the Liturgical Movement in the time immediately before and during the Second Vatican Council. Cluny Media has done the Church a great favor in reprinting it.

Joseph Tuttle is a Catholic freelance writer and author. His work has appeared in or is forthcoming from Word on Fire Blog, The St. Austin Review, New Oxford Review, The University Bookman, and Aleteia among others. He is the author of An Hour with Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen (Liguori, 2021) and a contributing author/editor of Tolkien and Faith: Essays on Christian Truth in Middle Earth (Voyage Comics, 2021). He graduated cum laude with a B.A. in Theology from Benedictine College.