“Our gathering song is number 867 in the red book….” Everyone stands. The music starts. The servers and priest enter. For many Catholics in the United States, this is how Mass begins. One almost never hears priests, cantors, and other parishioners referring to the “Entrance Chant,” “Offertory Chant,” and “Communion Chant,” despite the fact that these are the official terms for these parts of the Mass.

Before going further, I want to be clear: My intention is not to condescend to or berate the musicians and singers who give themselves in service to the sacred liturgy. Not at all. Many parish musicians wish they were given more support, more formation, and more resources. Usually, they are the ones whose sense of duty and devotion has emboldened them to charge into the largely thankless field of parish music ministry, where they too often suffer the whims of priests and the complaints of their fellow parishioners.

No, this article is not meant to be a gotcha for music ministers or a pedantic scolding for pastors. It aims merely to identify and explain the official terms for the singing that occurs at several key points of the Mass and to encourage the adoption of the official terms in place of idiosyncratic expressions like “gathering song” or “opening hymn.”

A Brief History

The traditional practice of the Roman Rite is to sing antiphons at the entrance, offertory, and Communion of Mass. An antiphon is a short text, usually a line of Scripture, relevant to the liturgical day being celebrated. The antiphon precedes, is inserted within, and follows, the verses of a psalm. The antiphons for a given Mass are part of it, just as the Collect or Prayer after Communion are. The antiphons contribute to the identity of the particular Mass being celebrated.

In fact, it is even customary to refer to a given Mass by the first few words of its entrance antiphon, since this is the first text proper to that Mass. For instance, a Mass for the dead is called a Requiem Mass because the entrance antiphon begins Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine (“Eternal rest, grant unto them, O Lord”). Likewise, the third Sunday of Advent is called Gaudete Sunday and the fourth Sunday of Lent Laetare Sunday after their entrance antiphons.

Before Vatican II, the Missale Romanum contained antiphons for the entrance, offertory, and Communion. The sung versions of each Mass’s antiphons with their verses were found in the Graduale Romanum as well as other collections such as the Liber usualis.1 There were even adapted versions, such as the “Rossini propers”2 for parishes that might need easier versions of the chants. Whether the choir sang the antiphons or not, the priest always recited them at the proper times from the Missal.

The practice of singing vernacular hymns during low Mass, in itself legitimate, created the sense among the faithful that the Mass itself is recited and that hymns are added to Mass at key points, such as the beginning, the offertory, Communion, and the end. Many parishes still labor under this misconception.

When Mass was not sung but only recited (a Missa lecta or “low Mass”), many parishes had the custom of singing hymns at the points during the Mass where the proper antiphons would otherwise be sung. The 1958 instruction De musica sacra expressly permitted the singing of vernacular hymns during low Mass.3 However, the practice of singing vernacular hymns during low Mass, in itself legitimate, created the sense among the faithful that the Mass itself is recited and that hymns are added to Mass at key points, such as the beginning, the offertory, Communion, and the end. Many parishes still labor under this misconception.

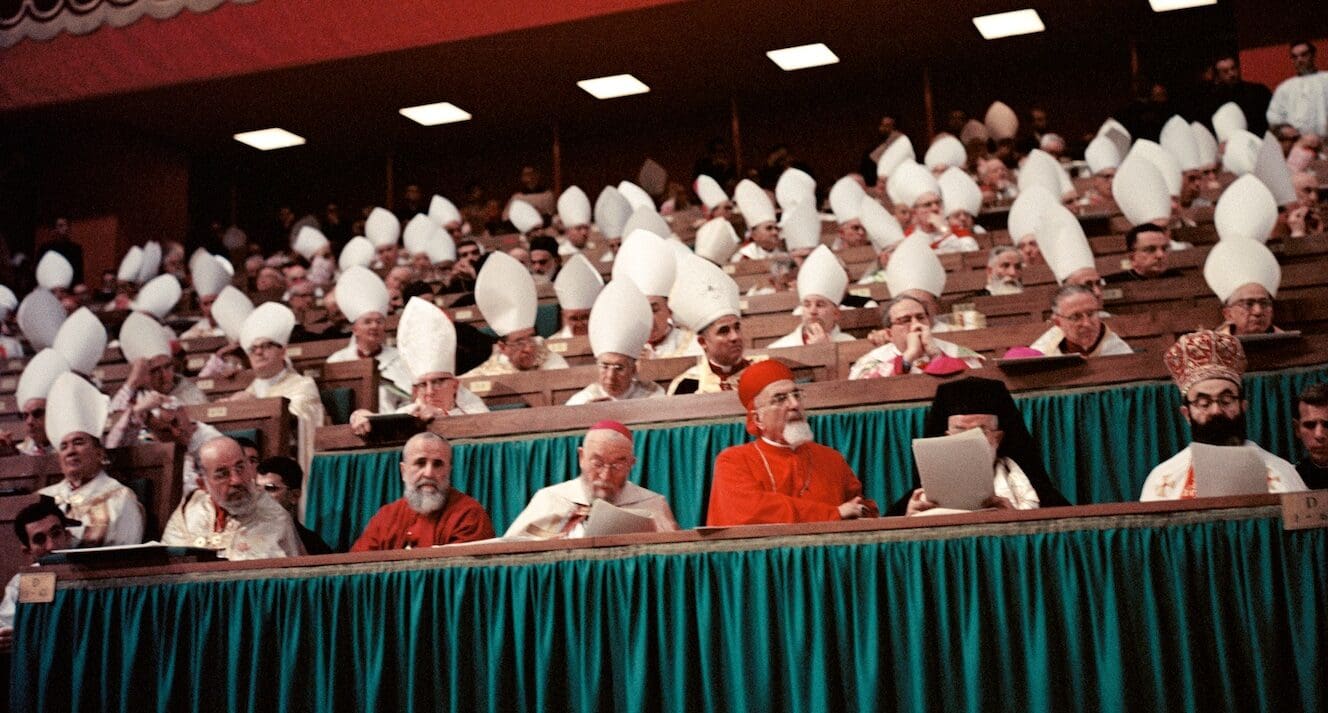

The reform surrounding Vatican II aimed to move away from the idea that only the priest and ministers in the sanctuary are responsible for the liturgy. The vision of full, active, and conscious participation meant that the congregation should not be excluded from the liturgical texts themselves—in this case the proper antiphons. Instead of being busied with separate devotional singing while the priest recited the real texts of the Mass, the people would also join in the antiphons or at least hear them sung by the choir. To this end, Vatican II called for the revision of the official chant books and the publication of a collection of simple chants for smaller churches.4 The Graduale simplex in usum minorum ecclesiarum (“Simple Gradual for the Use of Smaller Churches”), published in several editions from 1967 on, is a fruit of this directive. Thus, a forceful and somewhat famous notice in Notitiae from 1969 explained that the provision of De musica sacra, 33, allowing the congregation to sing hymns while the priest recited the antiphons, had been superseded by the reform. “It is the Mass, Ordinary and Proper, that should be sung, not ‘something’…. This means singing the Mass and not just singing during the Mass.”5

“It is the Mass, Ordinary and Proper, that should be sung, not ‘something’…. This means singing the Mass and not just singing during the Mass.”

Like the pre-Vatican II editions of the Missale Romanum, the short-lived 1964 Roman Missal, whose instructions for celebrating Mass remained in Latin, spoke of the “antiphona ad Introitum,” “antiphona ad Offertorium,” and “antiphona ad Communionem.”6 The 1964 instruction Inter Oecumenici and the 1967 instruction Tres abhinc annos maintained these terms.7 However, the 1967 instruction Musicam sacram spoke more broadly of the “cantus ad introitum,” “cantus ad offertorium,” and “cantus ad communionem,” and also used the description “cantus ad processiones introitus et communionis” (“chants for the entrance and Communion processions”).8 It also acknowledged the legitimacy of the regional custom of substituting other songs (alios cantus) for the chants of the Gradual.9 When the Novus ordo Missae was promulgated in 1969, this way of speaking entered the Missal itself. What in Musicam sacram had been descriptions crystallized as proper names in the 1969 Missal.

Broad Terms Adopted

Two factors especially influenced the adoption of the broader terminology (speaking generally of cantus instead of only specifically of the antiphons). First, a discrepancy was introduced between the antiphons to be sung and the antiphons to be recited. That is, there would be one antiphon text meant for singing and another—often entirely different—to be recited when the antiphon was not sung.10 The sung antiphons would be found in the Graduale Romanum or Graduale simplex, while the antiphons for recitation would be found in the Missal itself. This difference dovetailed with the decision that in the Novus ordo Missae the Offertory antiphon should be omitted when not sung with the result that there are no Offertory antiphons in the modern Missale Romanum or Roman Missal, whereas the sung Offertory antiphons are still found in the Graduals.

Second, there was the choice to continue allowing the substitution of other sung texts for the antiphons and to codify this possibility in the Missal itself. This meant that what was being sung at the entrance, offertory, or Communion might not be the antiphon at all but instead something else. Naturally, if the antiphon was only one possibility, a more general term was needed to cover the other possibilities. Unfortunately, in most parishes, “something else” became the usual experience, with the majority of Catholics probably having no idea that the proper antiphons even exist.

Like Musicam sacram, the 1969 Institutio generalis Missalis Romani (IGMR), used the terms “cantus ad introitum,” “cantus ad offertorium,” and “cantus ad Communionem” to describe what is sung at the entrance, at the offertory, and at Communion.11 The Latin terminology has remained unchanged up through the current edition of the Missale Romanum.12

In contrast, the official English renderings of these terms have changed several times over the years. The initial 1969 General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM) used the names “entrance song” and “offertory song” for the first two chants. It rendered cantus ad Communionem as both “the song during the communion” and “communion song” due to the rephrasing of other grammatical elements in the relevant Latin instruction.13 These English terms remained the same when the complete translation of the 1969 Missale Romanum was published as the 1974 Sacramentary.14 However, in the 1985 Sacramentary, which served as the English-language implementation of the 1975 edition of the Missale Romanum, these chants came to be called: “entrance song,” “presentation song,” and “communion song.”15

By 1998 the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) had drafted a fresh English translation of the Missale Romanum. In this 1998 draft Sacramentary, the three chants discussed in this article were referred to as: “opening song,” “song for the preparation of the gifts,” and “Communion song.”16 Although essentially complete, ICEL’s 1998 Sacramentary never received approval from the Holy See and thus never came into parish use. The draft was scrapped and a new version begun, which eventually became the Roman Missal now in use since 2011. One of the factors prompting a new English version was the promulgation of the third major edition of the Latin Missale Romanum in 2000, appearing in 2002. Another was the 2001 instruction from the Holy See on translating liturgical texts, Liturgiam authenticam. Yet another was friction between the Holy See and ICEL, and the institution of the Vox clara committee to work with ICEL on future translations.

While work on a complete English translation of the 2000/2002 Missale Romanum was beginning, a provisional rendering of the new GIRM was published in 2003 so that rubrical changes could be more easily introduced into English-speaking regions even before the full Missal was ready. In this 2003 GIRM, the three chants are called: “Entrance Chant,” “Offertory Chant,” and “Communion Chant.”17

The 2007 document, Sing to the Lord, prepared by the Committee on Divine Worship of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), incorporates the terminology of the 2003 GIRM, but it also employs a variety of descriptions it treats as more or less synonymous. For instance, it speaks of “the Entrance chant,” “an Entrance chant or song,” “Entrance song or chant,” “the Entrance chant or song,” “the Entrance song,” and “the Entrance Chant (song).”18 In any case, the English terminology of the 2003 GIRM became official with the promulgation of the complete Roman Missal that was introduced in parishes in 2011.19

The following table summarizes the history:

|

Liturgical Book or Text |

Terminology Used |

|

1962 Missale Romanum |

antiphona ad Introitum, antiphona ad Offertorium, antiphona ad Communionem |

|

1964 Roman Missal |

antiphona ad Introitum, antiphona ad Offertorium, antiphona ad Communionem |

|

1967 Musicam sacram |

cantus ad introitum, cantus ad offertorium, cantus ad communionem cantus ad processiones introitus et communionis |

|

1969 Missale Romanum – 2008 Missale Romanum |

cantus ad introitum, cantus ad offertorium, cantus ad Communionem |

|

1969 General Instruction of the Roman Missal – 1974 Sacramentary |

entrance song, offertory song, song during the communion / communion song |

|

1985 Sacramentary |

entrance song, presentation song, communion song |

|

1998 draft Sacramentary (never promulgated) |

opening song, song for the preparation of the gifts, Communion song |

|

2007 Sing to the Lord |

Entrance chant or song, Offertory chant or song, Communion chant or song Note: this document also uses a great variety of other descriptions |

|

2003 preliminary General Instruction of the Roman Missal 2011 Roman Missal |

Entrance Chant, Offertory Chant, Communion Chant |

Understandably, when the 2011 Roman Missal was implemented, more effort went into helping ministers and congregations learn the changes in the Mass prayers than into explaining the terminology of “Entrance Chant,” “Offertory Chant,” and “Communion Chant.” However, now, a decade after the new English translation of the Missal, and nearly two decades after the 2003 translation of the GIRM, many parishes remain unaware of the official names of these three chants, continuing to use a hodgepodge of idiosyncratic terms when announcing hymn numbers or filling out liturgy planning sheets.

Clarity in Terms

What are we to make of “Entrance Chant,” “Offertory Chant,” and “Communion Chant”? Each term consists of two words. They are capitalized, which identifies them as proper names. The Entrance Chant is not just a chant that happens to be sung at the entrance but is the proper name of a part of the Mass. The use of the definite article (which Latin lacks) underscores the same point: it is the Entrance Chant, not just a chant during the entrance.

Each term’s first word, as a modifier, identifies the particular procession or event that the sung text accompanies: the entrance procession, the procession with the gifts, and the Communion procession. The singing of the texts at these points in the Mass are not independent rites or acts, like the Gloria or responsorial psalm. Instead, they belong to the class of sung texts that accompany another rite.20

The second word in each term is “chant.” The translators of the Missale Romanum had a variety of options for turning the word cantus into English. “Song,” “singing,” “chant,” and “chanting” can all be legitimate translations of cantus. Why not render cantus ad introitum as “the singing at the entrance” or leave it as “entrance song” like it was in the 1969 GIRM and the subsequent editions of the Sacramentary?

There are several reasons for using the word “chant.” One is the normative value of Gregorian chant. “The main place should be given, all things being equal, to Gregorian chant, as being proper to the Roman Liturgy.”21 Even apart from the particular significance Gregorian chant has for the Roman Rite, the word “chant” has a sacral connotation that “song” lacks. Other words, such as “hymn,” also have religious connotations, but “hymn” would exclude the proper antiphons, which are decidedly not hymns.

Why Adopt the Official Terms?

Why should parishes use the official terminology? One reason is simply that it is official. These terms are standardized, not idiosyncratic. Calling these three chants what the Missal calls them would lead to greater consistency. Printed hand missals and missalettes generally use the official terms, so if the cantor announces a “gathering song,” parishioners who are following along may wonder what happened to the Entrance Chant mentioned in the missalette. It even happens that within the same parish one cantor might say “gathering song” while another says “entrance hymn.” All this creates confusion and gives the impression that the Church has nothing official to say about what is sung at these points during the Mass.

Another reason to use the official terms is that they are not used in other contexts. You might hear “opening song” at a concert; “Entrance Chant” signals that you’re in church. As mentioned above, the official terms also highlight the connection between these chants and the processions they accompany. They are not extraneous musical pieces inserted into the Mass or simply sung while Mass is going on. They are companion chants to the sacred actions taking place.

Finally, deliberately using the word “chant” serves as a reminder that the sung antiphons remain the ideal—they are texts of the liturgical books themselves, part of the particular Mass being celebrated—and that Gregorian chant is proper to the Roman liturgy. Even when Gregorian chant is not actually used (would that it were!), the official terms help to keep it from being forgotten entirely. The vice-regent is not the king, no matter how absent the king may sadly be.

Official Silence: Singing at the End of Mass

The liturgical books are generally silent about singing at the end of Mass, with exceptions such as funerals, where a chant accompanies the procession from the church to the cemetery, and other special situations. As far as typical Masses go, the 2011 GIRM states: “Then the Priest venerates the altar as usual with a kiss and, after making a profound bow with the lay ministers, he withdraws with them.”22

The custom of singing at this time is certainly not contrary to the rubrics, but we are left with a lacuna. There are official names for the Entrance, Offertory, and Communion Chants, but what should we call the singing that accompanies the procession at the end of Mass? For the following four reasons, I submit “Recessional Chant” as a possibility.23

First, the term “Recessional Chant” is congruous with the official names of the other chants. Second, it clearly identifies that this chant accompanies a procession. Third, other options such as “Departure Chant” or “Exit Chant” are jarring and clearly have the wrong connotations or register. Fourth, the 2008 Missale Romanum uses the Latin word “recedit” (not, e.g., “exit”) to describe the action of the priest and ministers as they leave the sanctuary.24 Therefore, “Recessional Chant” seems an appropriate option.

Words Matter

Saying “Entrance Chant” instead of “gathering song” may seem like a small matter. Doesn’t the Church have bigger problems? Indeed, she does. But the smallness of the matter is an advantage. Adopting the official terms for these parts of the Mass is one of the easiest changes regarding liturgical music that most parishes can make. But once that change is made and becomes familiar, a parish is one step closer to the ideal of singing the Mass, not just singing at Mass. Names make a difference. And a small but intentional effort to use the official terminology from the Missal now can help guide parishes to more fruitful reforms in the future.

Father Dylan Schrader is a priest of the Diocese of Jefferson City, MO. He holds a Ph.D. in systematic theology from the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

- There were slight textual differences between the pre-Vatican II Missale Romanum and the 1908 Graduale Romanum, but nothing like the discrepancies between the post-Vatican II versions of these books.

- Rev. Carlo Rossini, ‘Proper’ of the Mass for the Entire Ecclesiastical Year (1933).

- Sacred Congregation of Rites, De musica sacra (September 3, 1958), no. 33, in Acta Apostolicae Sedis [AAS] 50 (1958): 643.

- Sacrosanctum Concilium, no. 117.

- Notitiae 5 (1969): 406.

- Roman Missal (New York: Catholic Book Publishing Company, 1964), Ritus servandus in celebrratione Missae, sections IV, VII, and XI.

- Sacred Congregation of Rites, Inter Oecumenici (September 26, 1964), no. 57b, in AAS 56 (1964): 891; and Tres abhinc annos (May 4, 1967), no. 18c, in AAS 59 (1967): 446.

- Musicam sacram (March 5, 1967), nos. 31, 32, and 36, in AAS 59 (1967): 309–310.

- Musicam sacram, no. 32, in AAS 59 (1967): 309.

See St. Paul VI, Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum (April 3, 1969), in AAS 61 (1969): 221.- 1969 IGMR, nos. 25, 50, and 56i.

- 2008 IGMR, nos. 37, 47, 74, and 86. The Ordo cantus Missae (first published in 1970, with a second edition in 1988) speaks of the antiphons and not of broader cantus (1988 Ordo cantus Missae, nos. 1, 13, and 17), but that is because the focus of this book is precisely to establish how the antiphons from the old Graduale Romanum should be organized for the post-Vatican II Missal.

- International Committee on English in the Liturgy, The General Instruction and the New Order of Mass (Hales Corner, Wisc.: Priests of the Sacred Heart, 1969), GIRM, nos. 25, 50, and 56i. The 1969 IGMR, no. 56i: “Dum Sacramentum a sacerdote et fidelibus sumitur, fit cantus ad Communionem, cuius est spiritualem unionem communicantium per unitatem vocum exprimere […].” The 1969 GIRM, no. 56i: “The song during the communion of the priest and people expresses the union of the communicants who join their voices in a single song […].”

- Sacramentary (Huntington, Ind.: Our Sunday Visitor, 1974), GIRM, nos. 25, 50, and 56i.

- The Sacramentary (New York: Catholic Book Publishing Company, 1985), GIRM, nos. 25, 50, and 56i.

- The Sacramentary, vol. 1.1 (Washington D.C.: International Commission on English in the Liturgy, 1998), GIRM, nos. 25, 50, and 56i.

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal (Washington, D.C.: United States Catholic Conference, 2003), nos. 47, 74, and 86.

- Sing to the Lord (Washington, D.C., United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2007), nos. 30, 139, 140, 142, 144, and note 110.

- 2011 GIRM, nos. 47, 74, and 86.

- 2011 GIRM, no. 37.

- 2011 GIRM, no. 41.

- 2011 GIRM, no. 169.

- Sing to the Lord speaks variously of a “closing song,” “recessional,” “recessional hymn,” and “a hymn or song after the dismissal” (nos. 30, 44, 115, and 199). However, I believe “Recessional Chant” offers greater consistency with the 2011 GIRM.

- See 2008 Ordo Missae, no. 145; 2008 IGMR, nos. 169 and 186. Cf. 2008 Caeremoniale Episcoporum, no. 185.