Times of change or transition are commonplace in our human experience. Such moments, both large and small, can be opportunities for renewal and refocus. The purchase of a new car or wallet offers us the prospect and resolution of keeping the new one cleaner than the one replaced. For Catholics the movement from Ordinary Time to the season of Lent is a transition often associated with spiritual and liturgical renewal. Each celebration of the sacrament of Penance is also a moment of transition, allowing us an opportunity for conversion from sin to new life.

Over the last several years, the English-speaking Church has been receiving revised translations of her liturgical books, and each of these is also a moment of change and thus an opportunity for renewal and revitalization. Some of these transitions were of seemingly larger import, such as the 2011 reception of the newly translated third edition of the Roman Missal. Others are more modest in their changes and impact. This is perhaps the case with the most recently revised liturgical book, The Order of Penance (OP). Nevertheless, this moment still has the potential for a renewed focus on this sacrament and its liturgical celebration.

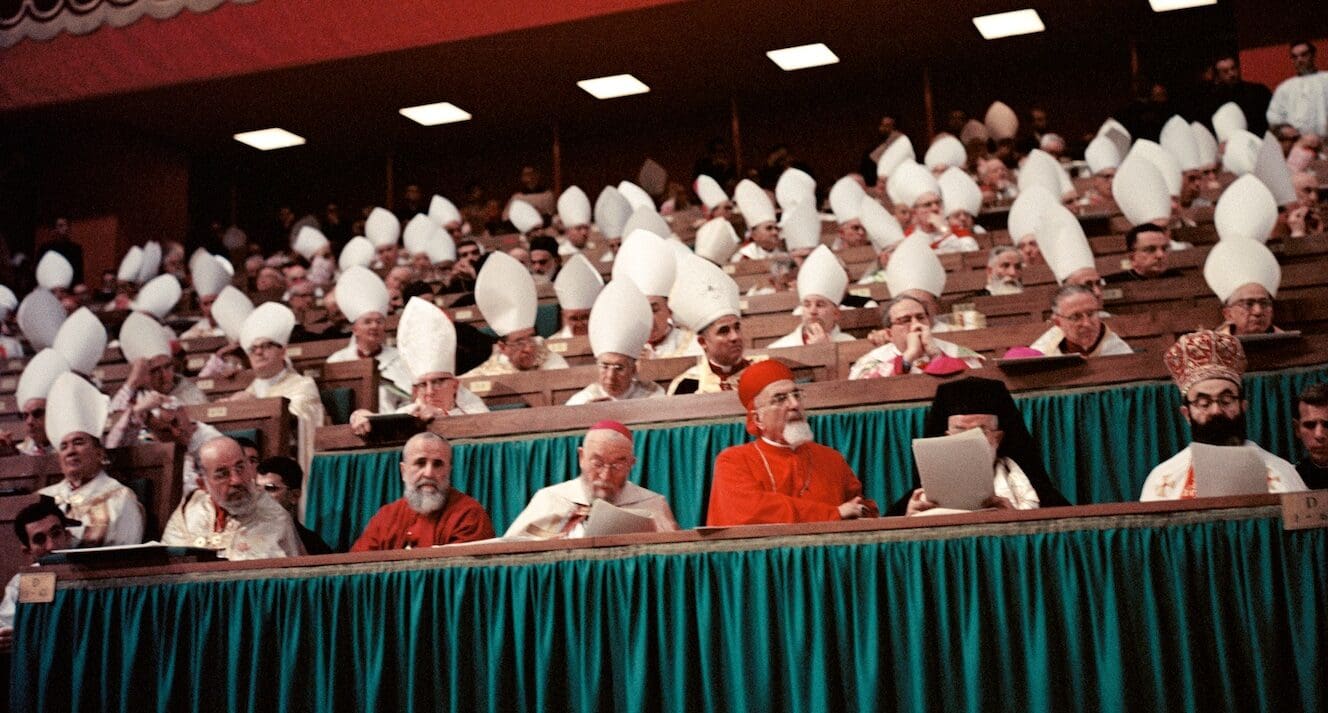

Fruit of Vatican II

Before considering the recent changes in translation, it may be helpful to revisit the genesis and contents of the Order of Penance itself.1 Vatican II’s Constitution of the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC), was rather sparse in its directives regarding this sacrament: “The rite and formulas for the sacrament of penance are to be revised so that they more clearly express both the nature and effect of the sacrament” (SC, 72). In 1966, the commission tasked with implementing Sacrosanctum Concilium, known as the Consilium, undertook the study and revision of the rite. The members of the Consilium considered the existing Tridentine rite, older Western forms of penance, as well as practices of the Eastern Churches. There was a widespread desire that individual confession would be supplemented by a form of communal celebration. Some members also hoped for multiple formulas of absolution from which to choose. The work was not without difficulty and the new rite was promulgated only after many modifications and after the work of two different committees. One of the main reasons for the prolonged preparation was the question of general absolution, the practice of which some Consilium members were hoping to expand. In response, in 1972 the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issued Pastoral Norms on the Administration of General Absolution. A new study group was formed to rework the draft in keeping with these new norms. As a result, the post-conciliar rite was published in 1973 with not one, but three forms: the Order for Reconciling Individual Penitents, the Order for Reconciling Several Penitents with Individual Confession and Absolution, and the Order for Reconciling Several Penitents with General Confession and Absolution.

The post-conciliar rite was published in 1973 with not one, but three forms: the Order for Reconciling Individual Penitents, the Order for Reconciling Several Penitents with Individual Confession and Absolution, and the Order for Reconciling Several Penitents with General Confession and Absolution.

The praenotanda, or Introduction, to the Order of Penance serves as a kind of theological and pastoral overview of the sacrament. The pre-conciliar rite contained its own introduction, but this newly composed and theologically rich text “intended to synthesize the traditional doctrine, theology, and practice as set out by the Council of Trent and nuanced by Vatican II.”2 It begins with richly biblical language, placing reconciliation within the larger context of salvation history, highlighting its trinitarian, Christological, and ecclesiological foundations (OP, 1). It shows the connection between Penance and the other sacraments, particularly baptism and the Eucharist (OP, 2). It goes on to consider reconciliation in the life of the Church, which is at once holy but always in need of purification (OP, 3). Here it highlights both the personal and communal dimension of sin and reconciliation (OP, 5). The Introduction then outlines the essential parts of the sacrament, what the tradition has recognized as matter—contrition, confession, satisfaction—and the form—the words of absolution (OP, 6).

The Introduction then turns to the offices and ministries in the celebration of this sacrament. Notably, it begins with “the whole Church, as a priestly people” as the first subject of the work of reconciliation (OP, 8). It then turns to the priest as the minister of the sacrament and some words on his pastoral exercise of the sacrament (OP, 9-10). Finally, it considers the role of the penitent (OP, 11). The celebration of the sacrament is detailed in terms of its place, time, and vestments (OP, 12-14). The Introduction then walks through details of celebrating each of the three forms of the rite (OP, 15-35) as well as non-sacramental penitential celebrations (OP 36-37). We may be less familiar with these non-sacramental celebrations as they are not frequently utilized. Their existence shows that penance, even in its liturgical manifestation, is not limited in the life of the Church to the sacrament of Reconciliation. These are “gatherings of the People of God to hear the word of God, which invites them to conversion and to renewal of life as well as announces our freedom from sin through the Death and Resurrection of Christ” (OP, 36). One could imagine such services being used with children preparing for their first confession, with catechumens or candidates for full communion, or in communities where priests are unavailable to hear confession for a long period of time. The Introduction then closes with the various adaptions within the competence of the conference of bishops, the diocesan bishop, and the minister of the sacrament (OP, 38-40). Needless to say, each aspect of the Introduction is a fitting subject for further study.

The Order of Penance then devotes a chapter each to the three liturgical forms of the sacrament, beginning with the form Catholic faithful are most familiar with, reconciling individual penitents. This form begins with the reception of the penitent which includes a greeting by the priest, the sign of the cross, and an invitation to the penitent to trust in God. There follows an optional reading from scripture, a feature of individual confession regrettably underutilized. Next comes the confession of sins and the acceptance of satisfaction or penance, followed by the “prayer of the penitent,” usually known as the Act of Contrition. The Order provides a number of texts for this prayer (OP, 85-92). The new translation now includes for the first time the Act of Contrition familiar to many Catholics (“O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended you…”). The penitent’s prayer is then met with the absolution of the priest. The celebration ends with the proclamation of praise of God and the dismissal of the penitent.

The new translation now includes for the first time the Act of Contrition familiar to many Catholics: “O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended you…”

The second form highlights the communal nature of the sacrament. This is the order of reconciling several penitents with individual confession and absolution. Colloquially, many Catholics might recognize this as a “penance service” they experience at Lent or Advent. This celebration begins in the church where all are gathered with introductory rites that include a song, greeting, and opening prayer akin to a collect at Mass. There follows an ampler celebration of the Word of God, the structure of which mirrors the biblical readings at a Sunday Mass. There is then a homily and a collective examination of conscience. The Rite of Reconciliation begins with a general formula of confession of sins. This is not an enumeration of individual sins, but a corporate acknowledgement of sin and the need for God’s mercy. The Lord’s Prayer is said and, after this, penitents disperse to individual confessionals for individual confession and absolution. The liturgy envisions that penitents remain in the church after their individual confessions for a proclamation of praise for God’s mercy, a concluding prayer of thanksgiving, and the concluding rites which include a blessing and dismissal.

This revised prayer of absolution may be used as of Ash Wednesday, February 22, 2023, and its use is obligatory as of April 16, 2023. Here follows the new approved text, with changes in bold:

God, the Father of mercies,

through the death and resurrection of his Son

has reconciled the world to himself

and poured out [vs. “sent”] the Holy Spirit for the forgiveness of sins;

through the ministry of the Church may God grant [vs. “give”] you pardon and peace,

and I absolve you from your sins

in the name of the Father, [sign of the cross] and of the Son,

and of the Holy Spirit.

Amen.

The third form is the order of reconciling several penitents with general confession and absolution. Sometimes known simply as “general absolution,” this form does not include the individual, integral confession of sins. The rather narrow applications of this form of the sacrament are dictated by the Code of Canon Law §961-963, as well as the Introduction to the Order of Penance, 31-34. In short, this form may be used in two scenarios. First, general absolution may be granted if danger of death is imminent and there is not sufficient time for individual confessions. One might imagine here soldiers going into battle, or passengers on a sinking ship. Second, the diocesan bishop may determine that there is other grave necessity which, due to the number of penitents and lack of confessors, would preclude individual confession (and thus possibly the grace of Eucharistic communion) within a suitable period of time (the complementary norm of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) interprets this as one month). One could envision such a case particularly in mission territories or other locales that are rarely visited by a priest. In general, the rite follows the pattern of the second form above, with a few exceptions. First, a brief instruction is given regarding the proper interior disposition for the sacrament, including an intention to confess individually at a proper time the sins that cannot be confessed at this time. The penitents then indicate their desire for absolution by a sign such as kneeling and are invited to make a general act of confession (“I confess to almighty God…”). Absolution is given with the usual formula, or a version containing an expanded tripartite prayer. The celebration concludes with a short proclamation of praise, blessing, and dismissal. In cases of extreme need, such as imminent danger of death, the rite can be shortened even to include simply the essential words of absolution.

The fourth chapter of the Order of Penance includes various texts to be used in the celebration of reconciliation. The variety of texts given for the prayer formulas and scripture readings highlights a treasury of options rarely taken advantage of. The texts are often rich in scriptural quotations or allusions, and provide ample material for a mystagogical catechesis on this sacrament.

Finally, several helpful appendices outline the procedures for the absolution from censures, dispensation from irregularities, as well as several examples of non-sacramental penitential celebrations for a variety of occasions.

New Translation of Order of Penance

The revised Order of Penance is not a revision of the rite itself or even another edition from what was previously in use. It represents a fresh translation of the first (and only) Latin edition from 1973 in line with the 2001 Instruction Liturgiam authenticam, which lays out the guidelines for translations of liturgical texts into vernacular languages. The International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) prepared the translation according to these principles, and the USCCB voted in June 2021 to approve the translation for use in the United States. In April 2022 the Dicastery for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments approved the text. The new translation may be used beginning Ash Wednesday 2023 and will be mandatory as of Divine Mercy Sunday (Second Sunday of Easter) 2023.

Some might first observe the modification of the title. The Rite of Penance is now the Order of Penance. This reflects the Latin title, Ordo Paenitentiae. It also recognizes that, generally speaking, an ordo is a collection of rites, as is the case in this liturgical text.

The new translation may be used beginning Ash Wednesday 2023 and will be mandatory as of Divine Mercy Sunday (Second Sunday of Easter) 2023.

The most noteworthy changes are found in the formula for absolution. Catholics have been used to hearing, “God the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of his Son has reconciled the world to himself and sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins.” The new text will read “poured out the Holy Spirit for the forgiveness of sins.” The new translation is, in the first place, closer to the Latin original. The words “among us” do not appear in the Latin and have thus been removed. “Poured out” renders more faithfully the Latin effudit. More than mere literalism, however, the revised text captures much of the biblical language about the mission of the Holy Spirit. Liturgiam authenticam notes that “the manner of translating the liturgical books should foster a correspondence between the biblical text itself and the liturgical texts of ecclesiastical composition which contain biblical words or allusions” (49). The Holy Spirit is often spoken of as being “poured out” in the sacred scriptures, such as on the day of Pentecost in fulfillment of the prophesy of Joel (Acts 2:17, 33). Consider also Romans 5:5 where Paul tells us that “God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us.” This pouring out of the Spirit is intimately connected to the forgiveness of sins. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church says, “Because we are dead or at least wounded through sin, the first effect of the gift of love is the forgiveness of our sins” (CCC, 734). Certainly, the Holy Spirit has been “sent among us,” but the language of pouring out stresses the superabundance of the divine generosity (see CCC, 731).

While the revised translation becomes mandatory later this year, it is important to note that the continued use of the previous language would not invalidate the sacrament.

A second and even more subtle change to the formula comes when the priest says “through the ministry of the Church may God give you pardon and peace.” The revised text will now read, “may God grant you pardon and peace.” While for the simple verb “give” one might expect a form of the Latin dare, the Latin of the rite is tribuat. The latter can mean give, but it seems to have a broader semantic range than dare. Tribuo has the sense of grant, bestow, or assign. In English, “grant” carries a higher linguistic register than “give” and is often used in legal contexts or is accompanied by a formal act. Though no strict rule applies, it seems more fitting to say that the sun “gives” heat, while the state “grants” certain rights. This slightly elevated way of speaking is fitting for the sacrament; as Liturgiam autheticam states, “it should cause no surprise that such language differs somewhat from ordinary speech. Liturgical translation that takes due account of the authority and integral content of the original texts will facilitate the development of a sacral vernacular, characterized by a vocabulary, syntax and grammar that are proper to divine worship” (47). In a private correspondence with this writer, Msgr. Andrew Wadsworth, executive director of ICEL, said that “there is a powerful suggestion here that God ‘grants’ rather than simply ‘gives’ pardon and peace as a result of the ministry of the Church in this sacrament. So, there is a desire to strengthen the idea of God’s agency in granting forgiveness in direct response to the Church’s request.” Thus, the minor change from “give” to “grant” is also a sacramental sign that more clearly reveals both God’s action through the Church and the dignity of the reality unfolding in sacramental absolution.

While the revised translation becomes mandatory later this year, it is important to note that the continued use of the previous language would not invalidate the sacrament. Force of habit can be hard to overcome, and it would be understandable if priests who have recited the formula of absolution countless times may, on occasion, use the form to which they have become accustomed. In that case, the penitent need not be concerned that his sins are not forgiven. Indeed, the Introduction to the Order of Penance tells us that “the essential words are: ‘I absolve you from your sins, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit’” (OP, 19). These words remain untouched by the new translation.

Transition and Opportunity for Renewal

The Order of Penance is likely one of the least frequently utilized liturgical books. The rather simple structure of individual confession, along with its frequent repetition in the ministry of most priests, makes continual reference to the text somewhat superfluous. Nevertheless, we hope that this moment of change will also be an opportunity to refresh and renew the Church’s liturgical practice and vision for the sacrament of Penance. While shorter aids are already being produced that include the changes to the rite, it should be hoped that acquiring the revised Order of Penance will be an occasion for clergy and laity alike to revisit the rich liturgical options it provides as well as the theological and pastoral vision it contains.

Mike Brummond holds a Doctorate in Sacred Liturgy from the University of St. Mary of the Lake, Mundelein Seminary, IL. He is associate professor of systematic studies at Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology in Hales Corners, WI.

Footnotes

- For details on the work of the Consilium, see Annibale Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975 (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1990), 664-683; James Dallen, The Reconciling Community: The Rite of Penance (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1991), 205-215).

- James Dallen, The Reconciling Community, 227-228.