In order to track a Luciferian serial-killer, Robert Downey, Jr’s film-version of world-famous master sleuth Sherlock Holmes singly enters into a satanic ritual in the first installment of the Sherlock Holmes movie franchise. While it is repugnant, ill-advised, arrogant, and reveals typical ignorance of playing around with things demonic, the fictional character makes an obvious point: one can enter into the mind of a person and figure out his intentions and mental habits by entering into the rituals that he regularly practices.

While an Enlightenment character like Holmes may see himself as above religious ritual—and even see religious practice as pre-scientific—he still sees the value of understanding cult to understand the mindset of a person and a community. In this essay, cult is defined as religious ritual or practices and has no intrinsic negative connotation. Cult is simply what provides context and insight to understand the way a practitioner or protagonist views the world and interactions between God and man or between man and spirits.

Before modern secularist political movements emptied culture of appeals to higher but unseen spiritual realities, religious cult defined culture and therefore shaped a person’s worldview. Not only did religious cult deeply and daily affect home and hearth, cult gave context and reference to legends both local and national. If one wishes to enter an ancient author’s cultural and historical mindset, if one wishes to understand the author’s context and audience, then knowing his cult—his ritual practices—becomes even more relevant to identify when he is applying such cult—as practiced in his day—to ancient legends of mankind’s origins and similar theological narratives. For instance, is the cult established at Mount Sinai applied to narratives of Eden when Moses gives the Torah?

For proper exegesis of Sacred Scripture, the authentic tradition and voice of Scripture’s guardian is clear: “The interpreter [of Scripture] must investigate what meaning the sacred writer intended to express and actually expressed in particular circumstances by using contemporary literary forms in accordance with the situation of his own time and culture. For the correct understanding of what the sacred author wanted to assert, due attention must be paid to the customary and characteristic styles of feeling, speaking and narrating which prevailed at the time of the sacred writer, and to the patterns men normally employed at that period in their everyday dealings with one another” (Dei Verbum, 12).

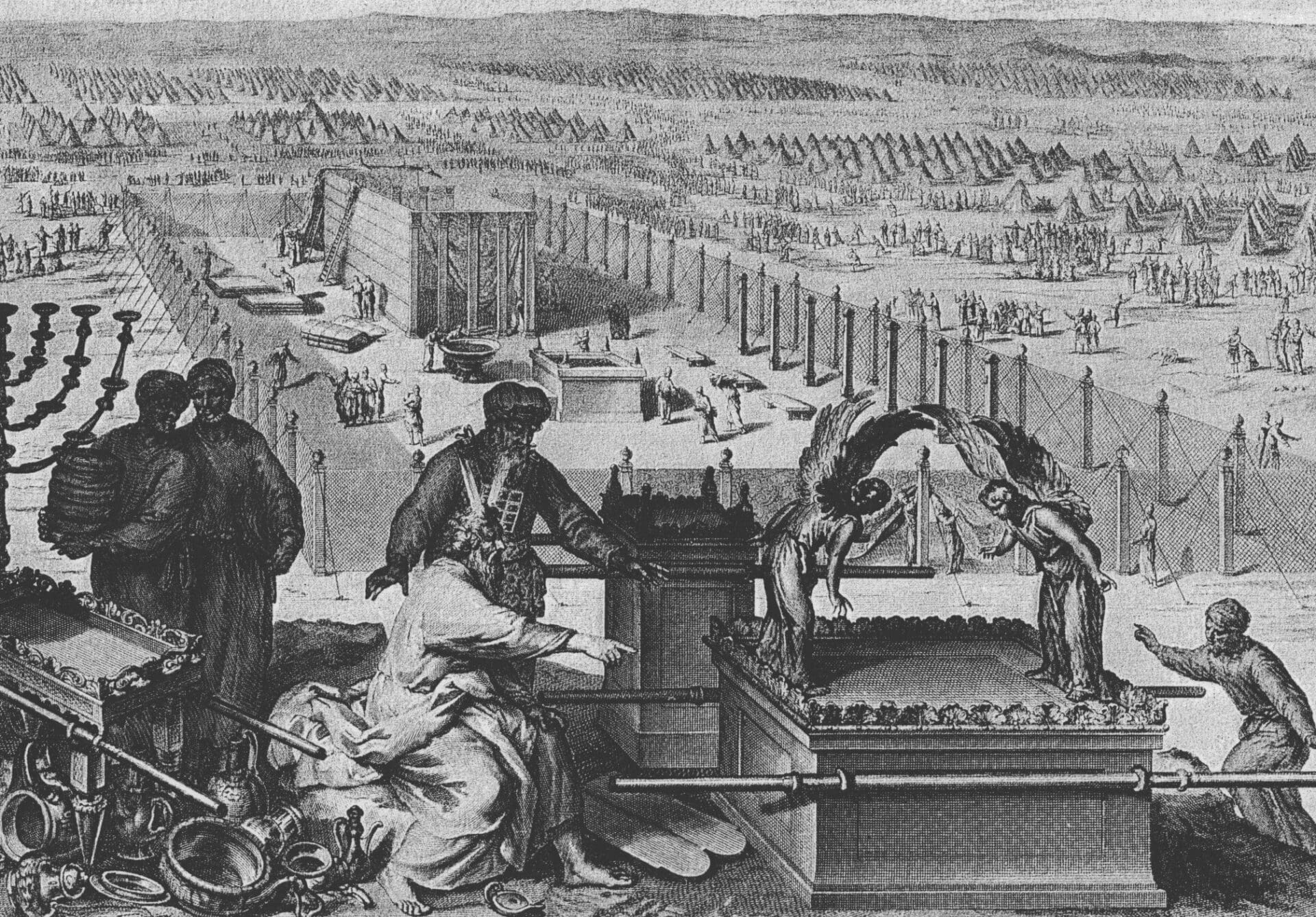

The relevance of these principles for the exegesis of the Torah, and the use of cult to enter the culture and context of the human sacred writer, becomes more clear when we recall that Moses—upon God’s revelation—instituted both the design of the temple (the Tent of Meeting, or Tabernacle) and the priesthood that would regulate the daily lives of the Israelite community. Once God revealed himself on Mount Sinai, and once Moses instituted that pattern in the Tabernacle and in the priesthood, then all previous narratives received a final form and were purified of all previous misconceptions. The Tabernacle itself gave a purified cosmology and understanding of creation; while the furnishings inside the temple and the Levitical priesthood established a sacramental worldview and expectation of a future Messiah.

Most important to all of these considerations, since Moses would not have delivered a Genesis narrative in its final form before the events of Exodus took place at Sinai (with the institution of the Tabernacle and priesthood), then we should watch for how the liturgical and cultic events of the Exodus at Sinai gave penultimate context to the Genesis narrative.

Sinai to Genesis

Prior Israelite traditions of Creation and Eden could not have received a final1 canonical form before Moses experienced the Exodus along with all of Israel. If Moses is to be the substantial author of the written Torah, he most certainly did not first write Genesis and then go to Egypt to begin the Exodus and then communicate the Book of Exodus. The Exodus experience was communicated first and its language and idioms give cultural context and clues to a proper exegesis of Genesis (which was communicated finally after the Exodus). A book of Genesis, apart from the Exodus, would never have been written as we have it today had not the Exodus of Moses been successful. It was the Exodus that preserved Israel from being re-absorbed into other cultures and gave final form to Genesis. Everything depends on the success and traditions of the Exodus (including Leviticus and Numbers) in order for there to be a people to even receive the written Law and Scriptures which we celebrate today—and ultimately, in order for there to be the Book of Genesis we have today.

Before modern secularist political movements emptied culture of appeals to higher but unseen spiritual realities, religious cult defined culture and therefore shaped a person’s worldview.

Certainly, before Moses there were prior written and oral traditions about gardens of the gods and accounts of man’s beginnings, long before the Israelites and even circulating popularly amongst the Israelites in Egypt who had their own traditions. Umberto Cassuto, the renowned professor and chair of Biblical studies at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, mentions such sagas and poetry in his eight lectures on the Documentary Hypothesis and in formulating his theory of sources:

“It is no conjecture…that a whole world of traditions was known to the Israelites in olden times…. From all this treasure, the Torah selected those traditions that appeared suited to its aims, and then proceeded to purify and refine them, to arrange and integrate them, to recast their style and phrasing, and generally to give them a new aspect of its own design, until they were welded into a unified whole.”2

The focus of this essay is that whatever those accounts may have included or however they may have served as material with which Moses and his lawful successors worked, the final canonical form to those narratives was established by the events and revelations of God himself at Mount Sinai, particularly beginning in Exodus 19. They were faithfully continued in the shared and public reality of liturgy as the tradition.3 Mount Sinai necessarily served as the interpretative key to whatever should be preserved from prior traditions and whatever should be discarded. It “recast the style and phrasing” of previous legendary material and imprinted its form on what became Genesis. Thus, there is necessarily an interplay of finalization of form in that prior traditions—which eventually helped form the Book of Genesis, and which preceded the Exodus—gave some preliminary shape to the Book of Exodus. However, and simultaneously, the Exodus event gives rise to what became the final form imposed on Genesis, especially upon the accounts of creation and the Garden of Eden. Stated as clearly as possible: Exodus recast the style and phrasing of what became Genesis.

Cult and Creation

Since any Israelite receiving Moses’ accounts of creation would already be celebrating the liturgies established in Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, then an Israelite would read Genesis through that daily existing context of worship, Tabernacle, and culture—a culture that was imbued already with the Exodus as the lens through which it understood God and the Land4 it was to inherit. This is why the Exodus actually gives a final form to Eden and Genesis.

Joseph Ratzinger is clear that the “giving of the ceremonial law [Tabernacle and worship] in the book of Exodus…is constructed in close parallel to the account of creation. Seven times it says, ‘Moses did as the Lord had commanded him,’ words that suggest that the seven-day work on the tabernacle replicates the seven-day work on creation.” In this passage, Ratzinger prepares the reader to recall an ancient understanding: the building of a temple is a microcosm of God’s creation, so the “account of the construction of the tabernacle ends with a kind of vision of the sabbath.”5

A book of Genesis, apart from the Exodus, would never have been written as we have it today had not the Exodus of Moses been successful.

Immediately after connecting the seven-part sequence of Moses building the Tabernacle to the seven-day work of creation and how they explain one another, Joseph Ratzinger implicitly bequeaths a similar principle of exegesis to the one this essay seeks to develop: “Creation looks toward the covenant, but the covenant completes creation.”6 Likewise, pre-Mosaic traditions of Eden look toward the Exodus, but the Exodus completes Genesis. In a book on liturgy, Ratzinger is expressing implicitly how the covenant of Mount Sinai and the Tabernacle give the final form to understanding correctly the meaning of the days of creation, especially the Sabbath. Liturgy establishes context for the written Torah.

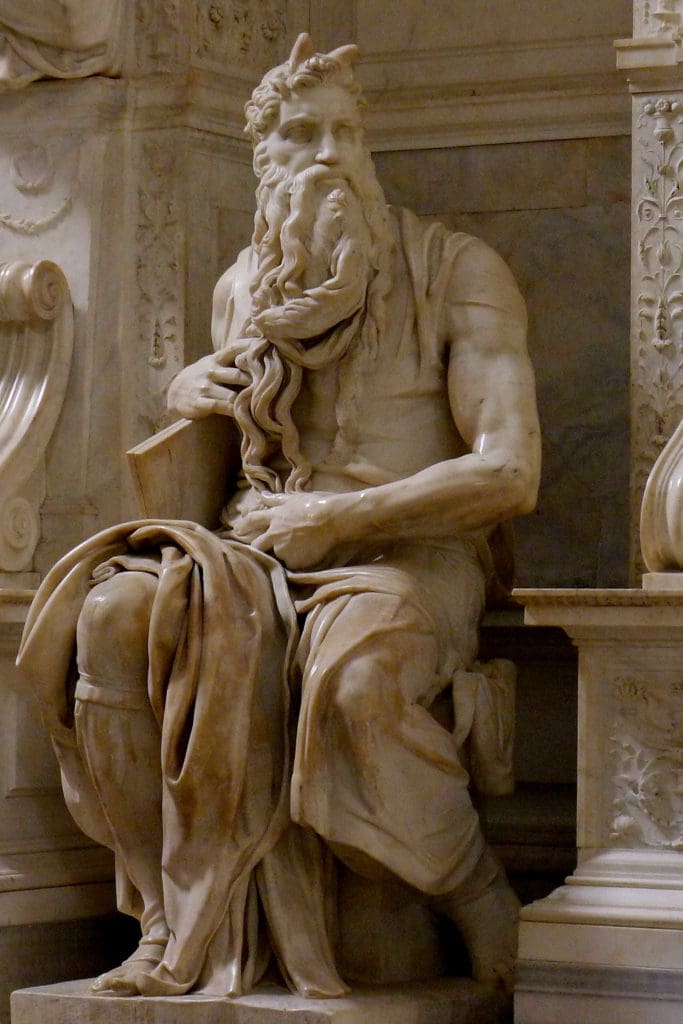

Ratzinger clearly states that the Exodus explanations of the Sabbath finish contextualization of the seventh day of creation. Central to understanding Moses’ substantial authorship of the Torah is understanding with Ratzinger that the “essential work of Moses was the construction of the tabernacle and the ordering of worship, which was also the very heart of the order of law and moral instruction.”7 This “essential work” is minimally what this essay views to be the substantial authorship of Moses: establishing the worship and cult that gives context to anything written in the Torah.

Angelic Guardians

Examples of how Exodus gives final form and phrasing to Genesis are helpful at this point. For starters, how would an Israelite during the time of the wandering in Numbers and through the time of Solomon’s Temple hear or read an account of a cherubim guarding the way to Eden? After all, the doors to the entrance of the inner sanctuary of Solomon’s Temple were covered with “carvings of cherubim, palm trees, and open flowers” (1 Kings 6:32) and immediately connect the Israelite’s mind with Eden. And, Solomon’s Temple was in imitation of the Tabernacle or the Tent of Meeting as expressed with the cherubim sewn into each of its ten curtains in Exodus 26:1. An Israelite would read Genesis through the context of essential authorship of Moses: the worship established by Moses, the Tent of Meeting (also seen in anticipation of the Tabernacle),8 and the moral instruction which Ratzinger listed. He would read it through what was most central and essential to the community and through the habitual worship practiced daily in the midst of Israel. He would know what the Tabernacle symbolized: Eden. For Israelites, daily worship and life—centered around the Tent (cf. Exodus 33:10)—created cultural context through which the Eden of Genesis necessarily was understood by the time Moses (and his successors) communicated a finalized Edenic narrative.

Such a finalized narrative was written after the theophany at Mount Sinai in the architecture of both the Tabernacle and in Solomon’s Temple and in the language of Genesis. It is well-established that the theophany before all of Israel at Mount Sinai both established a template for Israelite temple architecture and furnishings, and what eventually became the liturgies associated with the Temple.9 Sinai was first reflected in the Tabernacle and later in Solomon’s Temple and always pointed to the true Holy of Holies (cf. Hebrews 10:19; 12:18-22).

Mount Sinai necessarily served as the interpretative key to whatever should be preserved from prior traditions and whatever should be discarded.

Again, and to continue the example, how would an Israelite living through the time of Numbers read the canonical account of a cherubim guarding the way into Eden? He would see in it an account of the Tent and Moses going in and out of the Tent per Exodus 33:9: “When Moses entered the Tent, the pillar of cloud would descend and stand at the door of the tent, and the Lord would speak with Moses.” It was not necessarily the pillar speaking with him: “And when Moses went into the tent of meeting…he heard the voice speaking to him from above the mercy seat” (Numbers 7:89).10 It is nearly impossible to miss the implications except for a reading method that does not observe basic exegesis: we must enter the mind and culture of the human author which was an Exodus culture (whether it was Moses or prophets on his seat after him).11 Just as Moses went in and out of the Tent as he chose; so before the Fall, Adam and Eve went in and out of Eden as they chose until they were excommunicated and the cherub was stationed there to block re-entrance.

As children, many of us are catechized that Genesis “happened” before Exodus, and so readers think of the whole work of Genesis as written or finalized before the Book of Exodus. We thereby are conditioned to miss everything Genesis wants to disclose in terms of the Exodus experience, idioms, and cult. Properly nuanced, it must be remembered that the Exodus gave final literary form to any prior material tradition which eventually became the Book of Genesis. There is an angel, a cherubim with a flaming sword turning every way and guarding the way into Eden, because the people of the Exodus saw this very thing every time Moses entered a symbolic Eden (the Tent of Meeting) during the wandering after the great theophany at Mount Sinai. Recall, the fiery theophany on Sinai manifested God descending upon the cherubim and was the work of “elemental spirits” (cf. Galatians 4:3).

Pre-Lapsarian Radiance

Whenever Moses went into the Tent, he would come out radiating light from his face (cf. Exodus 34:34-35; 33:11), just as when he came down from Mount Sinai: “When Moses came down from Mount Sinai…the skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God” (Exodus 34:29; cf. 33:9). His face “shone” whenever he entered the Tent and spoke with the Lord (cf. Exodus 34:34-35; 33:9). An angel, the Pillar of Cloud, would stand at the entrance and implicitly guard the way in from anyone else as the cherub did Eden. In this way, cherub engraved on entranceways of tents and temples take on deeper meaning than mere decoration.

The Tent and the Pillar of Cloud that would stand at the door of the Tent represented respectively: God’s presence on the mountain top in the glory cloud and the boundary that was forbidden to be crossed at the base of the mountain. One must recall that the boundary at the base of the mountain (Exodus 19:12-13, 21-23) threatened death to anyone who dared to cross it without invitation; much as the Tree of Knowledge was a border that clearly threatened death to any uninvited trespassers (“eat and you will die”).12

The Tent represented the Holy of Holies and the Pillar of Cloud represented the border into the Holy Place which no one could enter without the threat of death…like “a sword which turned every way” (cf. Genesis 3:24). Moses was entering a type of Eden every time he entered the Tent. “Whenever Moses went in before the Lord to speak with him, he took the veil off, until he came out; and when he came out, and told the sons of Israel what he was commanded, the sons of Israel saw the face of Moses, that the skin of Moses’ face shone” (Exodus 34:34-35). Mankind’s original access to God in Eden was being reflected in Moses as well.13

Israel’s exile from the Tent, and God’s first-born son exiled from Eden, inform one another; especially when reading that a cherubim with a flaming sword guarded the way into a holy place in Genesis 3:24. The Israelite experience in the Exodus gives final literary form to any previous tradition of Eden. At Eden, cherubim guarded a garden and sanctuary which had an even holier object at the very center, the Tree of Life. It is cherubim upon whom God descends in fire at Sinai as though on a cloud and as depicted by the cherubim overshadowing the ark of the covenant. Clearly the Pillar of Cloud was an angel—as Exodus 14:19 makes clear through a parallelism: “The angel of God…went behind them; and the pillar of cloud…stood behind them.” The same pillar of cloud was a pillar of fire by night; it both led the Israelites and was their guardian from the Egyptians.

A pillar of cloud turns in every way and would put the fear of death into anyone attempting to cross it in Exodus. Matching this, the cherubim of Genesis guarded the way into God’s sanctuary which was defined as Eden. The theophanic descent on Mount Sinai which revealed God’s presence and threatened death to trespassers was seen as a “devouring fire” (Exodus 24:17) and certainly represented a flaming “sword.” Wherever God joins heaven and earth in a unique way to give access to participation in his life-giving covenant, like at Sinai, it is a type of Eden. Even today, we see the Eucharistic celebration depicted as a walled city in the Book of Revelation and angels standing guard at each gateway (cf. Revelation 21:12,22; Hebrews 12:22).

Whenever Moses entered the Tent of Meeting and Tabernacle, he had access to God’s original and life-giving covenant pledged at the creation of the world. He walked out radiating light from his face which the Israelites beheld every time and so stood at the entrance of their own tents to watch repeatedly (see Exodus 33:10; cf. 34:34-35). This would have ingrained a certain way of perceiving the Edenic narratives in light of experienced events at Sinai. It would make clear how to perceive original man and woman, how to translate the Hebrew text into the Greek of the Septuagint regarding Moses’ face being “glorified” in Exodus 34:29, and the tradition St. Paul—trained by the great rabbi, Gamaliel (Acts 22:3)—communicates about the brightness of Moses’ face at the tent in II Corinthians 3.

Thus, the Exodus experience itself defines the interpretation of the written narratives that follow after the events. It is the point of reference for the culture that was founded upon it and the writings and idioms that came into existence through it. Genesis precedes Exodus in the order of narrative telling. However, it was finalized after the events of Exodus and received final literary form from the events of the Exodus. Genesis is read with the historical author’s mind only when read through the Exodus events. But this truth isn’t simply one of historical interpretation, for our current cult—the Catholic liturgy—similarly stands as the interpretive lens through which we come to see our faith more clearly and hold to it more firmly. And it is into this current cult and culture that we will enter in the second half of this essay.

Look for part II of Dr. Tsakinikas’s essay in a future issue of Adoremus Bulletin.

Matthew A. Tsakanikas is an associate professor of theology at Christendom College, Front Royal, VA, and editor of catholic460.com; the website where he makes available free manuscripts, videos, and articles. He also publishes on catholic460.substack.com.

Footnotes

- “Penultimate” could also be used to emphasize that the Messiah gives final form as Jesus led the ultimate Exodus.

- cf. Umberto Cassuto, The Documentary Hypothesis: Eight Lectures, trans. Israel Abraham (Skokie, IL: Varda Books, 2005 from Jerusalem: Central Press, 1941), 102. [Emphasis mine.]

- The phrase “liturgy as the tradition” emphasizes Henri Cardinal De Lubac’s focus of “scripture in the tradition.”

- cf. Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, trans. John Saward (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 19: “Sinai remains present in the Promised Land.”

- Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, 27.

- Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, 27.

- Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, 41. Emphasis mine.

- See: New American Bible, St. Joseph Edition (New York: Catholic Book Publishing Co., 1987), Footnote concerning Exod 33, 7-11; cf Umberto Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Exodus, trans. Israel Abraham (Skokie, IL: Varda Books, 2005 from Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1951), 429–432.

- This does not deny material influences from prior cultures. See also: Jeffrey Morrow, “Creation as Temple-Building and Work as Liturgy in Genesis 1-3,” in Journal of the Orthodox Center for the Advancement of Biblical Studies 2, no. 1 (2009): 1-13 (digital publication); cf. John Bergsma and Brant Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible: The Old Testament (Ignatius Press, 2018), 183 & 187.

- As noted previously, the tent anticipates the tabernacle of the meeting tent. The pillar of cloud was trying to show that the tent of meeting had replaced the resting glory cloud of Sinai until the tabernacle was built with all the furnishings. cf. Cassuto, Commentary on Exodus, 429-432.

- See: Vatican II, Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation: Dei Verbum (1964), #11-12; See also: Benedict XVI, Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation: Verbum Domini (2010), #34.

- See: current author, “Unmasking the Pharaoh in the Garden,” in Communio 47 (Spring 2020).

- See: current author, “Understanding Marriage Through Holy Communion,” in Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture, Volume 7:2 (Spring 2004).