Many liturgical reforms called for or attributed to the Second Vatican Council have been flashpoints ever since they were introduced. One post-Vatican II development that has garnered little discussion (much less controversy) has been the practice of celebrating the Sunday liturgy on Saturdays. The practice is so settled in the United States that questioning it seems almost akin to a politician grabbing on to the third rail of Social Security reform. Outside the United States, the practice seems to have varied reception: my experiences in England, Poland, and Switzerland were that it existed but clearly stood in the shade of Sunday. In China, where clergy are more limited, practice in the English-speaking expatriate community more closely resembled that in the United States.

Between the prudence of questioning a popular practice and the current pontificate’s apparent posture that any public doubts about the wisdom of any practices claiming a connection to the Second Vatican Council is liturgical revanchism, I will raise some questions about the practice of celebrating Sunday Masses on Saturdays. I do so because I maintain that the practice in its origins—as opposed to mythology about its origins—is wrought with various kinks that collectively affect coherent liturgical practice.

Where Did Saturday Night Mass Come From?

Pace an oft-repeated myth that celebrating Sunday Masses on Saturday nights was intended to put Catholics as “spiritual Semites”1 back in touch with their Jewish roots about beginning the day from sunset of the previous evening, the origins of the practice were far more canonical, convoluted, and, arguably, “pastoral.” Shawn Tunink’s 2016 thesis at The Catholic University of America for a licentiate in canon law, which I summarize and follow here, traces the path.2

The path to Sunday Masses on Saturday nights arguably comes, at least indirectly, from Sunday Masses on Sunday nights.

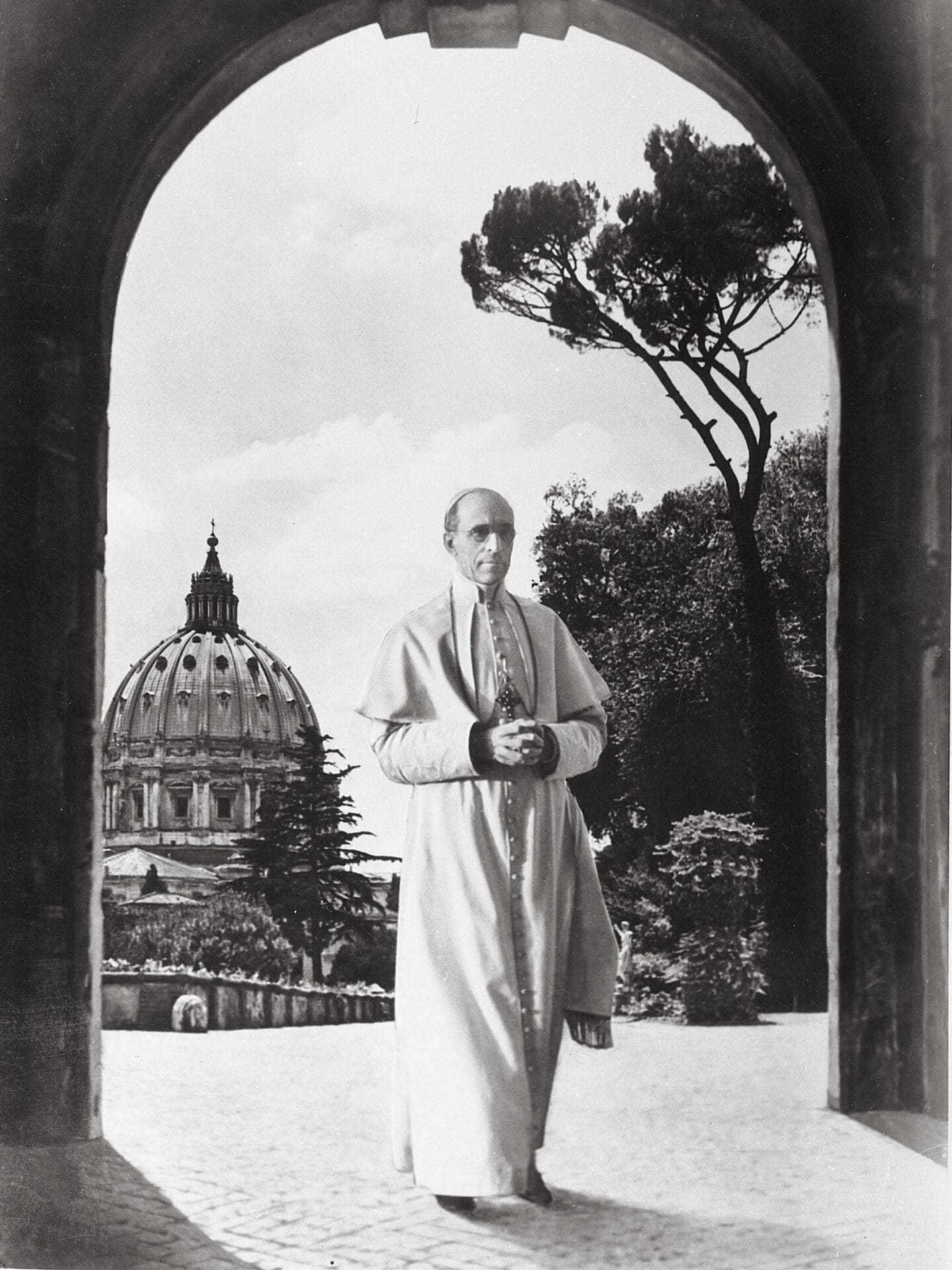

The path to Sunday Masses on Saturday nights arguably comes, at least indirectly, from Sunday Masses on Sunday nights. In the first half of the 20th century, the Eucharistic fast extended from the previous midnight, which practically anchored Sunday Masses to Sunday mornings.3 Tunink notes, however, that before Pope Pius XII’s mitigations of the Eucharistic fast in the 1950s, Rome had already thrice authorized Sunday evening Masses: (1) in the Soviet Union, (2) in Europe during World War II, and (3) for French prison chaplains in the immediate postwar period.4

After the War, two forces seemed to combine to make permission for Sunday evening Masses permanent: their popularity, especially in postwar occupied Germany, and changes to work schedules, often made with an underlying ideological edge. German Catholics liked Sunday evening Masses. The Polish bishops asked for Sunday evening Masses because the communist regime rearranged workers’ schedules to keep them away from churches. Some similar forces were probably operative as a post-French Revolution leftover in ever-laicité France.5 Broader permissions for Sunday night Masses were granted out of pastoral considerations, to “open up to the faithful a new source of grace”6 ever more broadly in Europe. When Pope Pius XII modified the Eucharistic fast—first in 1953 by excluding water from it and allowing additional non-alcoholic beverages, especially for clergy when faced with extended hours for celebration of Mass, then in 1957 by reducing the fast to three hours prior to receiving Communion—the groundwork was laid for Mass to be celebrated at any time on Sundays.7

How these two factors—their popularity and the pastoral permission to celebrate Mass later on Sundays to address changed work schedules—affected each other is a question I leave to historians. Expanded work schedules were cited to justify the accommodation, but whether European Catholics in democratic societies might have been more resistant to those demands if the Church did not accommodate them (and thereby inadvertently accelerating secularization), I cannot say.

What is important is that the precedent for changing canonical discipline about Mass times in the name of pastoral accommodation was made. In the 1960s, the accommodation would be made even more elastic through the canonical decision to treat Masses celebrated on Saturdays as fulfilling the dominical precept of attending Sunday Mass.

Already in 1964, Vatican Radio spoke about permissions granted in particular areas—usually in the name of the faithful’s limited access to priests and/or the limited number of clergy—to justify attending Mass on Saturday evenings to fulfill the Sunday Mass obligation.8 Permissions for that practice seem to have grown quietly in the Europe of the mid-1960s (anecdotally said to be especially in France) until, by 1967, the Sacred Congregation on Rites’ Instruction, Eucharisticum Mysterium (no. 28) formalized that the principles under such permissions could be granted.9 As Tunink notes, Eucharisticum Mysterium did not grant such permission but only stipulated the conditions under which they should be granted.10 The rationale was to give Christians greater facility to “celebrate the day of the Resurrection” provided it did not obscure “the significance of Sunday.” One might observe that, like Rome’s approval of the 1966 “pastoral statement” of the Catholic bishops of the United States to dispense from mandatory abstinence on non-Lenten Fridays provided some other act of voluntary penance was substituted,11 many Catholics seem to have adopted the permission but ignored the caveat.

It should be noted that the Catholic bishops of the United States thrice received Rome’s permission—in 1970, 1974, and 1979—to allow a Saturday evening Mass to fulfill the Sunday Mass obligation. They only ceased needing the permission because the 1983 Code of Canon Law made the permission universal and permanent.12

The historical record shows that the rationale for allowing a Saturday Mass to fulfill the dominical precept had nothing to do with theology and everything to do with canonical mandate.

What Is the Theological Basis?

The historical record shows that the rationale for allowing a Saturday Mass to fulfill the dominical precept had nothing to do with theology and everything to do with canonical mandate. In the context of the original decision to allow for Saturday evening celebration of Sunday Mass, there are no documents discussing the Jewish concept of the day as beginning the evening before, of Saturday evening Masses being some sort of “vigil,” of expanding our celebration of the Sabbath rest, or of any other justification from the viewpoint of liturgical theology. There was no rationale, only a clerical fiat empowered by canon law: competent ecclesiastical authority could declare Saturday night “counted” for Sunday—and that was that. Any theological justifications appear to be post-factum veneers applied to a legal fiction to regard Saturday night as “Sunday.”

No doubt defenders of the status quo would maintain that the decision was driven by a generous pastoral adaptation of Church law. While one can have a certain sympathy for such motivations, it does not free us from examining its other consequences.

Some proponents no doubt saw the extension of the dominical precept to include Saturday evenings as a further application of the pastoral generosity first expressed in permitting Sunday Masses on Sunday evenings. But nobody ever doubted Sunday evenings were part of Sunday. The problem was not making Sunday evening “part” of Sunday but overcoming the practical impact of the Eucharistic fast which began at midnight that would then extend for 16-20 hours.

That Saturday evenings were “part” of Sunday was a completely different kettle of fish. That the Church considered application of the dominical precept to Saturday evenings a canonical matter is reflected in the fact that, at first, the question was whether a Mass celebrated on Saturday evening using the liturgy of that Saturday fulfilled the precept. Even today, a Catholic who attends a Mass on Saturday evening that does not include the Sunday liturgy (e.g., a wedding), fulfills the dominical precept.13 So—as Tunink strongly points out—Saturday night Masses were never a question of extending Sunday14 but of extending the time one could fulfill the obligation to attend Mass on “Sunday.”

I would argue, then, that claims that Saturday night Masses mirror or somehow analogously follow Jewish liturgical practice of reckoning the day from the previous evening were after-the-fact justifications which sought to provide some theological rationale for a canonical decision. That this argument is wholly one-sided is evident from the fact that, as previously noted, Sunday evening Masses—even at 9 or 11 pm, as on some college campuses—still are Sunday Masses.

A Catholic who attends a Mass on Saturday evening that does not include the Sunday liturgy (e.g., a wedding), fulfills the dominical precept.

When Saturday night Masses were first introduced, the term used for them was “anticipated,”15 i.e., they anticipated the Sunday obligation to attend Mass. That term has, unfortunately, largely fallen by the wayside. One occasionally hears the claim that Saturday night Masses are somehow “vigil” Masses, but that term is wholly erroneous16 since, other than its initial bandying about, nobody speaks of the “Vigil of the 21st Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year C.” Vigils normally have their own, self-contained liturgies, e.g., the readings of the Easter and Pentecost Vigils—the Church’s greatest vigils—are utterly different from Masses during the day on those solemnities. The same is true of the Vigil Mass for the Assumption on the evening of August 14. On the other hand, regular Sunday Masses on Saturday nights simply use the Sunday readings.

The fact that they are not truly “vigil” Masses is also evident from the American holyday practice, adopted by the bishops in 1991, that waives the obligation to attend Mass on the Assumption, All Saints Day, or the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God if they fall on a Saturday or Monday. When Christmas falls on Sunday—as it did in 2022—the Solemnity preempts a lesser feast (which is why the Feast of the Holy Family is transferred to December 30) and Saturday, December 24,d features the lectionary of the Vigil Mass for Christmas. As Tunink observes, the Holy See dealt with “back-to-back” celebrations by invoking the calendar of precedence: the higher ranking feast prevails, even if the person attending that Mass intends to fulfill the obligation for the lower feast.17 The Catholic bishops of the United States merely closed the circle by dispensing the faithful from a “back-to-back” obligation.18

What Have Been The Consequences?

Answering this question depends on one’s perspective. If one’s sole motivation is passive “pastoral accompaniment” of the situation in which contemporary Catholics find themselves, these adaptations have been a great success. As many Catholics can attest, Saturday evening Masses are usually one of the best attended of Sunday Masses at the typical American parish.

For those who think that canon law should not be so autonomous from good theology and liturgy but, rather, their servant, and reject a version of canon law that simply treats the question as to whether the competent cleric can “dispense,” “extend,” or “anticipate” the Sunday “obligation,” the answer is more ambivalent. It would start with the question of whether the “obligation” should be driving, rather than deriving from, the theology of Sunday.

Despite the Holy See’s caveats that these pastoral accommodations should not dilute the preeminence of Sunday, that is exactly what happened. Like similar caveats that voluntary abstinence should not eviscerate the penitential meaning of Fridays or that earthen burial is preferable to cremation (tolerated as long as not undertaken out of resurrection-denying motives), an honest assessment is that the accommodations have greatly eroded the ideal.

Even if these pastoral accommodations were made out of good intentions, they presumed Catholic cultural conditions that were even then largely running on fumes. For consider: by the 1970s, business interests were actively opposing Sunday commerce bans and secularists were challenging blue laws as establishments of religion. Fifty years later, Sunday in the United States is only marginally different in quality from other days.19 It, along with the “Sunday” obligation, has been subsumed into a “weekend” in which religious duties compete with secular choices and responsibilities in an ever-pressing competition for the Christian’s time. I would add, from experience, that it seems the Catholic propensity to “adapt” has furthered this erosion: when I lived in the largely Protestant city of Bern, Switzerland, 2008-11, all major businesses started closing by 5 pm Saturday, the bells of the city’s churches pealed the Sonneneinleitung (the “invitation for Sunday”) around 7 pm, and everything was closed but restaurants and theaters on Sunday. Some bakeries operated until about noon; afterwards, one could only buy staple goods at gas stations on the highways or at a 24-hour shop in the central train station. In contrast, the Catholic city of Fribourg, also in Switzerland, 30 miles distant and with no such bans, was far more “American.”

Dies Domini20 laments the erosion of Sunday, but when “pastoral accommodation” refuses to take a stand for the religious rights of Catholics to keep Sunday holy—even out of good motives—it in fact simply fosters the further erosion of the unique identity of that day.

So Where Do We Go?

That, too, is a difficult question. As I pointed out at the beginning of this essay, questioning Saturday night Sunday Masses is politically and pastorally unpopular: why attack the likely best-attended parish Mass when overall Mass attendance among Catholics is plummeting? (This is especially true after we’ve all seen how the churches—what with retrospective irony Pope Francis calls “field hospitals”—were almost wholly evacuated during COVID.) This essay is designed as much to elicit discussion as provide answers.

I would urge that we stop “pastoral accommodations” that play to the Zeitgeist while offering limp lip service to principles we say Catholics “should” keep in mind (the uniqueness of Sunday or the penitential nature of Friday). The accommodation simply puts us on a slippery slope to undermining that principle.

We should stop making “pastoral accommodations” that, in the final analysis, put the canonical cart before the theological or liturgical horse. While the current pontificate is right to oppose “clericalism,” such “accommodations” are in fact just that. In the end, theology and liturgy are rendered inordinately subordinate to canon law and pastoral concerns.

The Church’s theological teachings on the unique status of Sunday is rowing against overwhelming cultural currents that ignore it.

If we are to think of the Saturday night Sunday Mass as somehow an extension of Sunday, then perhaps we need to think of it really in proximity to Sunday. In many dioceses, perhaps driven by lack of priests, Saturday night Masses are creeping earlier and earlier on Saturday afternoons, even to 3:30 or 4 pm. The earlier the Saturday “evening” Mass, the weaker the nexus to Sunday. My experience is that, in most dioceses, the “Saturday evening” Mass is almost always at 5 or 5:30 pm. Liturgy offices might want to encourage later Masses (which may have the effect of disclosing and challenging priorities, e.g., interfering with “going out on Saturday night”). Because these are not true “vigil” Masses, however, I hesitate to repeat the injunction Rome has normally applied to the Easter Vigil: that it occur after dark.

Finally, a renewed catechesis of Sunday is in order. The Church’s theological teachings on the unique status of Sunday is rowing against overwhelming cultural currents that ignore it. Our own liturgical scheduling in some sense abets those currents by turning Mass into an “obligation” to be stuck into the second half of the “weekend.” Yet our preaching and teaching about the Christian nature of Sunday is rarely heard.

An Excursus on Time

The French theologian and Archbishop of Cambrai, François Fénelon (1651-1715) observed that, in comparison to his other gifts, God is rather sparing on time. For an eternal God, all time is now; for us spatio-temporal humans, time is the context in which we must make choices and express priorities by his presence. The constant “pastoral” quest to “accommodate” demands on man’s time seems almost always to sacrifice the spiritual for the temporal, even though the physical needs no support to make its case.

The decision to treat Saturdays as Sundays for Mass purposes—like voluntary penance on Fridays, etc.—occurred in the context of a richer religious culture wherein its proponents could hope the Catholic tradition would survive. Half a century on, the truth is that the cultural signposts on which those “reformers” were depending are dramatically less prevalent, in part because the changes did not reckon with their own secularizing impact. In a modernity that values time perhaps even more than money, where one invests time speaks volumes of where one’s heart is (cf. Matthew 6:21).

The truth is we have reached a paradox. On the one hand, Sunday has practically ceased to be a shared, communal experience—at least if recent reports about churchgoing and doctrinal belief can be believed. The day set aside by and for the Lord has, for many, grown into a privatized fulfillment of an “obligation” at the local parish franchise whose Mass times are most convenient. At the same time, because time has communal significance, the vacuum created by the thinning of common religious practice has been filled by secular, especially commercial, pursuits: Country pop singer Shania Twain was not far off the mark when, regarding modern man’s pecuniary obsession, she observed: “Our religion is to go and blow it all/So it’s shopping every Sunday at the mall.”21 How many Catholics today, if asked what to associate “January 6” with, would say “Epiphany” rather than “Capitol attack?” What does that say about a Catholic sense of time?

John Grondelski (Ph.D., Fordham) was former associate dean of the School of Theology, Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ.

Footnotes

- Pope Pius XI used this expression in connection with opposing growing antisemitism in Germany: see https://ccjr.us/dialogika-resources/primary-texts-from-the-history-of-the-relationship/pius-xi1938sept6 . For an illustration of how this idea has been applied to scheduling Sunday Masses on Saturday evenings, see: https://aleteia.org/2017/08/04/why-is-sunday-mass-celebrated-on-saturday-evening/

- Shawn P. Tunink, “Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET).

- See 1917 Code of Canon Law, Canon 858, §1.

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), pp. 8-11. One wonders whether the indult for the USSR was part of the overall clandestine Russia evangelization effort that brought Jesuit Father and renowned Catholic evangelist Walter Ciszek there

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), pp. 8-11, esp. 10-11.

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), p. 10, quoting D. Ellard, “How Near Is Evening Mass,” American Ecclesiastical Review, 122 (1950): 333. See also Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), p. 11.

- Pius XII, Apostolic Constitution Christus Dominus (January 6, 1953), available at: https://www.papalencyclicals.net/pius12/p12chdom.htm; Motu Proprio Sacram Communionem, no. 2 (March 19, 1957), available at: https://www.papalencyclicals.net/pius12/p12fast.htm. In 1964, Pope St. Paul VI reduced the fast to one hour, which is incorporated into Canon 919, §1 of the current Code of Canon Law.

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), pp. 20-22.

- “Eucharisticum mysterium—Instruction on Eucharistic Worship,” May 25, 1967, available at: https://adoremus.org/1967/05/eucharisticum-mysterium/ Permission was granted to allow Christians “to more easily celebrate the day of the resurrection” without obscuring “the significance of Sunday.”

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), pp. 23–24.

- https://www.usccb.org/prayer-and-worship/liturgical-year-and-calendar/lent/us-bishops-pastoral-statement-on-penance-and-abstinence .For my commentary, see https://www.crisismagazine.com/2022/restore-year-round-friday-abstinence

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), pp. 23-25. Canon 1248 §1 provides that Catholics fulfill the Dominical precept through “assist at a Mass celebrated anywhere in a Catholic rite either on the feast day itself or in the evening of the preceding day….”

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), p. 23.

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), p. 23.

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), p. 3.

- Private email communication with Father J. Sabak, OFM, September 6, 2022. Father Sabak, Liturgy Director of the Diocese of Raleigh, NC, is a leading authority on vigils.

- Tunink, Evening Masses and Days of Obligation: Historical Development and Modern Norms,” J.C.L. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, 2016, available at https://archive.ccwatershed.org/media/pdfs/17/11/25/19-25-37_0.pdf (accessed October 12, 2022, 2000 ET), pp. 35-38.

- https://www.usccb.org/beliefs-and-teachings/what-we-believe/canon-law/complementary-norms/canon-1246

- I touched upon the palpable difference in how Americans observed Sunday when Independence Day 2021—one of the last federal holidays celebrated as a holiday—fell on a Sunday: see https://www.ncregister.com/blog/sanctify-sundays

- https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/1998/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_05071998_dies-domini.html

- https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/shaniatwain/kaching.html