Romans 12:1 must be one of Joseph Ratzinger’s/Benedict XVI’s favorite biblical quotations. It appears in many of his major works on the liturgy, and it is often used in his treatment of the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist. In this passage St. Paul writes: “I appeal to you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship” (Revised Standard Version). The idea of “spiritual worship” (Gr. λογικὴν λατρεία) is translated into the English language in various ways: the New International Version talks about “true and proper worship,” the Douay Rheims-American Edition about “reasonable service,” the American Standard Version about “spiritual service,” the Christian Standard Bible about “true worship,” the Phillips New Testament in Modern English about “intelligent worship,” the New American Standard Bible about “spiritual service of worship,” the New Catholic Bible about “a spiritual act of worship,” and the New English Translation about “reasonable service.”

In order to understand what this idea means for Ratzinger, we need to place it in the context of his general understanding of sacrifice in the Christian sense (St. Paul talks about “living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God”). In The Spirit of the Liturgy (SL), Ratzinger believes that the true meaning of the Christian sacrifice (i.e., the Mass) is “buried under the debris of endless misunderstandings” (SL, 27) and that this causes problems not only in the ecumenical dialogue with non-Catholic Christians, but also in the inner-Catholic theological and liturgical debate.

“I appeal to you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship.”

–Romans 12:1

Sacrifice before Christ

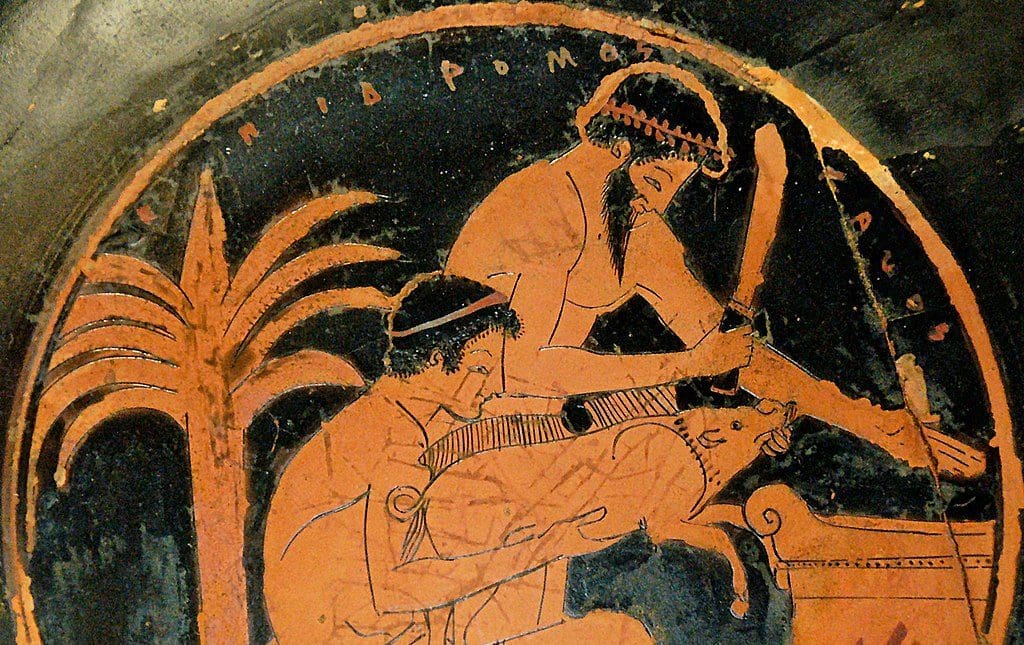

Ratzinger believes that “in all religions sacrifice is at the heart of worship” (SL, 27) and that the centrality of this concept in the history of religion is an expression of something important, a reality that concerns us as well (SL, 19). In pre-Christian religions, sacrifice was always associated with destruction and atonement: man, aware of his guilt, wanted to offer to God (or gods) something that would bring him forgiveness and reconciliation. At the same time, these attempts of arriving at reconciliation with the deity were always accompanied by a sense of inadequacy and insufficiency: the offering could always be only a replacement of the true gift, which is the man himself. Animals or fruits of the harvest could not possibly satisfy God and could only serve as an imperfect representation of the one who offers them.

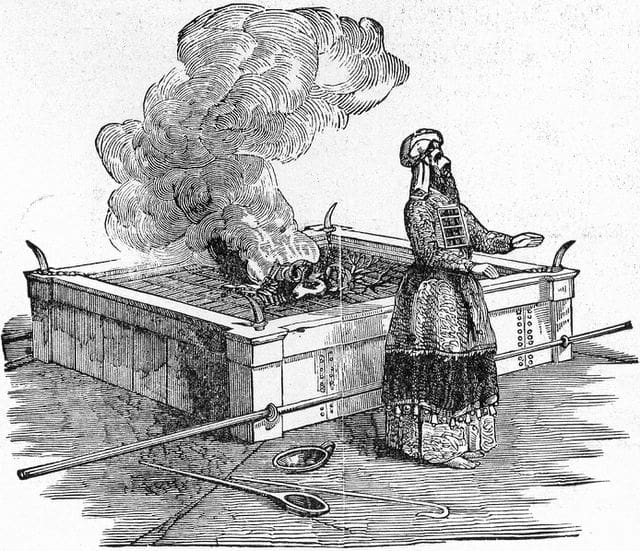

The same could be said about the sacrificial system of the Old Testament. Bloody sacrifices of animals were to be offered by priests to God in order to recognize his sovereignty and obtain his blessing. However, the Temple worship prescribed by the Law also “was always accompanied by a vivid sense of its insufficiency” (SL, 39). The People of God slowly and gradually came to realize that there was nothing that they could offer God who owns everything. God wanted something else: “More precious than sacrifice is obedience, submission better than the fat of rams!” (1 Samuel 15:22); “I desire steadfast love and not sacrifice, the knowledge of God, rather than burnt offerings” (Hosea 6:6). This was confirmed by God himself who, through the prophets, accused Israel of cultivating empty gestures that were not accompanied by an internal transformation of the heart: “If I were hungry, I would not tell you; for the world and all that is in it is mine. Do I eat the flesh of bulls, or drink the blood of goats? Offer to God a sacrifice of thanksgiving, and pay your vows to the Most High” (Psalm 50[49]: 12-14); or “I hate, I despise your feasts, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies. Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and cereal offerings, I will not accept them, and the peace offerings of your fatted beasts I will not look upon. Take away from me the noise of your songs; to the melody of your harps I will not listen” (Amos 5:21-23).

The true surrender to God consists in the union of man and creation with God. Belonging to God has nothing to do with destruction or non-being: it is rather a way of being. It means losing oneself as the only possible way of finding oneself.

A turning point came with the Babylonian exile. In a foreign land, there was no Temple, no public and communal form of divine worship as decreed in the law. Israel was deprived of worship and stood before God with empty hands. However, it was precisely this crisis situation that brought about a revision of the theology of worship in the Old Testament. It was precisely “the very emptiness of Israel’s hands, the heaviness of her heart, that was now to be worship, to serve as a spiritual equivalent of the missing Temple oblations.” It was Israel’s sufferings “through God and for God, the cry of her broken heart, her persistent pleading before the silent God, had to count in his sight as ‘fatted sacrifices’ and whole burnt offerings” (SL, 45).

The situation in which Israel found herself coincided with the encounter of the Greek critique of cult as such. This led to the development of the idea of λογικὴν λατρεία (θυσία): spiritual worship, worship according to the Logos, that is, according to reason. It is to this idea that Romans 12:1 alludes. In the Old Testament the People of God have finally came to realize that acknowledging God’s sovereignty over all things does not consist of destruction, but of something completely different. As Ratzinger states, “[the true surrender to God] consists in the union of man and creation with God. Belonging to God has nothing to do with destruction or non-being: it is rather a way of being. It means losing oneself as the only possible way of finding oneself (cf. Mark 8:35; Matthew 10:39)” (SL 28, “Theology of the Liturgy” (TL), 25).

At the same time, an important aspect is being added here by Ratzinger, through the influence of his great master, St. Augustine of Hippo. This transformation leading to union of human beings with God, which is the true and proper sacrifice pleasing to God, is not to be achieved only on the level of individuals, but on the level of community. Therefore, there is a very important ecclesiological component here in Ratzinger’s thought. Augustine teaches that the true fulfillment of the cult takes place when “the whole redeemed human community, this is to say the assembly and the community of the saints, is offered to God in sacrifice by the High Priest who offered himself” (City of God, X,8; see: TL, 25). In other words, “the sacrifice is ourselves…, the multitude: a single body in Christ” (TL, 25); “the true ‘sacrifice’ is the civitas Dei, that is, love-transformed mankind, the divinization of creation and the surrender of all things to God: God all in all (cf. 1 Corinthians 15:28). That is the purpose of the world. That is the essence of sacrifice and worship” (SL, 25).

The New Covenant and Eucharist

While linking the animal sacrifices with the idea of worship according to reason/Logos was a step in the right direction, human nature still consists of spirit and body. While the spiritual aspect of cult is primary and essential, human nature still longs for an external expression of this internal submission to God. This is where the Greek concept of λογικὴν λατρεία falls short since it does not do justice to the human pscyhosomatic condition—our natural struggle to express our spiritual dimension through physical means. This is where a final fulfillment of this idea arrives with the event of the Incarnation of the Logos, the Divine Son—in which, finally, God and man are met in one person, Christ.

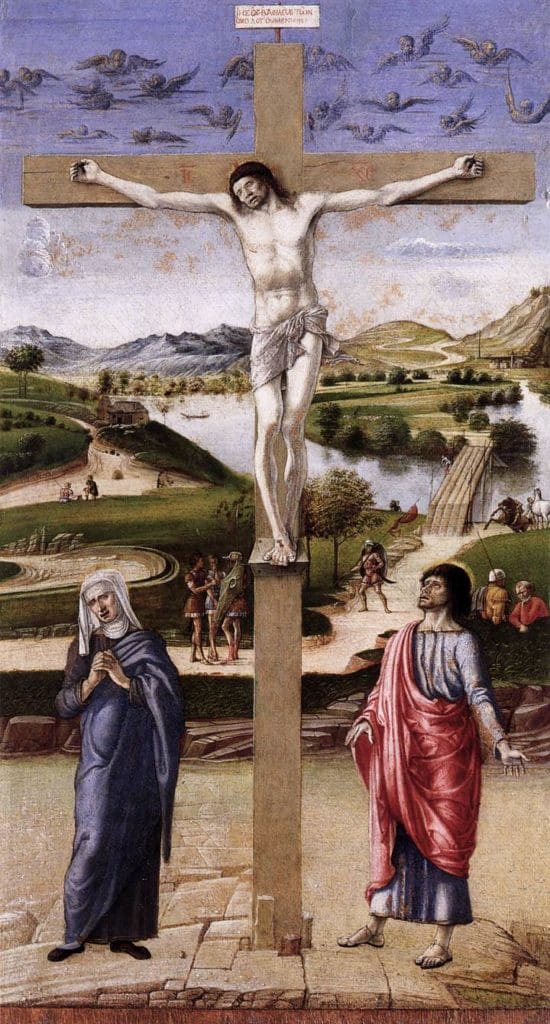

Ratzinger’s theology of Christ’s sacrifice is largely based on his reading of the Gospel of St. John and the Letter to the Hebrews. From Hebrews, Ratzinger takes the idea of Christ’s sacrifice being offered once and for all, at the altar of the cross, with Christ as the new and ultimate High Priest. From John he takes the idea of Christ being also the new temple—it is his humanity that Jesus has in mind when he announces: “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” (John 12:19). The event of the cleansing of the Temple is more than just an angry outburst against the merchants and the abuses that were taking place at that time. It is “an attack on the Temple cult, of which the sacrificial animals and the special Temple moneys collected there were a part” (SL, 43). Christ’s death on the cross, followed by the tearing of the Temple curtain into two, and then, in years to come by the physical destruction of the Temple, brought an end to the old economy of worship and inaugurated the new one: the true worship will now take place in the new Temple, in Christ himself, who is the dwelling place of the Father and the Spirit.

The longings of all pre-Christian religious systems and the Old Testament dynamism of worship are being fully realized in the sacrifice of the Mass.

Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross, however, is constantly re-presented by the Church when the sacrament of the Eucharist is celebrated. The once-and-for-all event reaches beyond the historical boundaries and spills over to the past and to the present: if we mention Abel, Abraham, and Melchisedek in the Roman Canon as those who also participate in the offering of the Eucharist, then in the celebration of the Mass we are dealing with something more than a simple memorial understood as remembering an important event from the past. As Ratzinger explains, the εφάπαξ, that is, Once For All, is bound up with the αἰώνῐος, that is, everlasting; and the semel, that is, once, bears within itself the semper, that is, always (SL, 56-57).

It is in the context of the Christian celebration of the Eucharist that Paul’s utterance from Romans 12:1 needs to be understood. Our “spiritual worship” consists of our submission to God “in spirit and in truth” (John 4:24). This submission is internal (spiritual), but also physical (bodily)—even if for “body” Paul is using the more generic Greek term σῶμα rather than the more specific σάρξ, there is no doubt that he is talking here about the whole person. This submission of the human person takes place not somehow in isolation, or in parallel with Christ’s submission to the Father represented in the Eucharist, but in deep relation to it. In the Eucharist, the spiritual element is combined with the physical component—through the visible signs and actions, invisible, spiritual realities take place. The longings of all pre-Christian religious systems and the Old Testament dynamism of worship are being fully realized in the sacrifice of the Mass where the physical offering cannot be just an empty gesture that may (or may not) express an internal disposition of the person. The person that offers this sacrifice, Christ himself, offers to the Father both his spirit and his body, and into this process of submission in love, the Church is being invited and drawn. The two sides of the same coin, the external offering and the internal disposition, in Christ become the reality, and they are perpetuated in the gift of the Eucharist.

Just as philosophy can prepare the ground for faith (“the God of the philosophers” is at the same time the Biblical God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob), the Greek idea of “spiritual/reasonable worship” can be understood as preparation for the true worship “in spirit and in truth” that comes with the revelation of the Incarnate Logos.

Worship: Reasonable, Spiritual, True

Ratzinger’s understanding of the concept of λογικὴν λατρεία in Romans 12:1 is indicative of the way he understands the general relationship between ideas that originate outside of Christianity, and the divine revelation that we know from the Bible and from Tradition. Just as philosophy can prepare the ground for faith (“the God of the philosophers” is at the same time the Biblical God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob), the Greek idea of “spiritual/reasonable worship” can be understood as preparation for the true worship “in spirit and in truth” that comes with the revelation of the Incarnate Logos. Christian scriptures and theology take up those non-Christian concepts and ideas that point to the right direction, and they fulfill them with new meaning, the ultimate meaning that comes with Jesus Christ, the Word (Logos) of the Father.

This fulfillment does not supplement the Christian revelation with something that it would not possess otherwise; but it helps to bring out and articulate those elements that are already there, even if it not always present in an evident way, or even if not perceived with ease. The dialogue between human reason and faith takes place in all areas of theology, including in the area of the liturgy and sacraments. Catholics have been long accustomed to uniting their own offerings with the Sacrifice of the Mass. Ratzinger’s analysis of Romans 12:1 helps us to understand even more the inner relationship that exists between the sacrifice of the altar and our own spiritual offerings that we bring to the Eucharist, so that the promised worship “in spirit and in truth” (John 4:24) may become an ever fuller reality in our lives.

Mariusz Biliniewicz currently serves as Director of the Liturgy Office in the Archdiocese of Sydney, Australia. He has worked at the University of Notre Dame Australia as Senior Lecturer in Theology and Associate Dean of Research and Academic Development. He has studied and worked in Poland, Ireland, and Australia, and has spoken and published internationally on a number of theological topics. His interests include contemporary Catholic theology, liturgy, sacraments, the Second Vatican Council, intersections between ecclesiology and moral theology, faith and reason, and general systematic theology.