Thanks to a long-standing friendship, your editor Chris Carstens knew that this is my year of retirement, and he asked if I could look in the rearview mirror and offer some comments about the field of liturgical studies: how I would evaluate the landscape, what I have seen change, what I have learned, etc. Relying on that friendship, I said no. Since I suffer the sin of singularity, I have mainly followed my own interests, and my blinders prevented me from paying the attention an academic should pay to what’s going on around him. But if I cannot say what has been going on in liturgical studies, perhaps Mr. Carstens (and you, gentle reader) will be satisfied with a reflection on what should be going on in liturgical studies, the ideal being more important than the practice.

I will sum up my prescription by saying that liturgical studies should be theologically dilated to comprehend the mystery of liturgy. Liturgy involves cosmology, anthropology, the doctrine of sin, the economy of salvation, Christology, ecclesiology, eschatology—roughly everything found along the liturgical path from the alpha to the omega. This might actually make liturgy an unsuitable topic for academic study—it is at least an unwieldy topic—because scholars like to keep their PhD dissertation topics small and under control, while liturgy is like triggering an inflatable raft in the closet. Liturgy is an activity of man, but it is the work of God. That’s why liturgy must be dealt with theologically.

If I cannot say what has been going on in liturgical studies, perhaps I can reflect on what should be going on in liturgical studies.

Eternal Dimensions

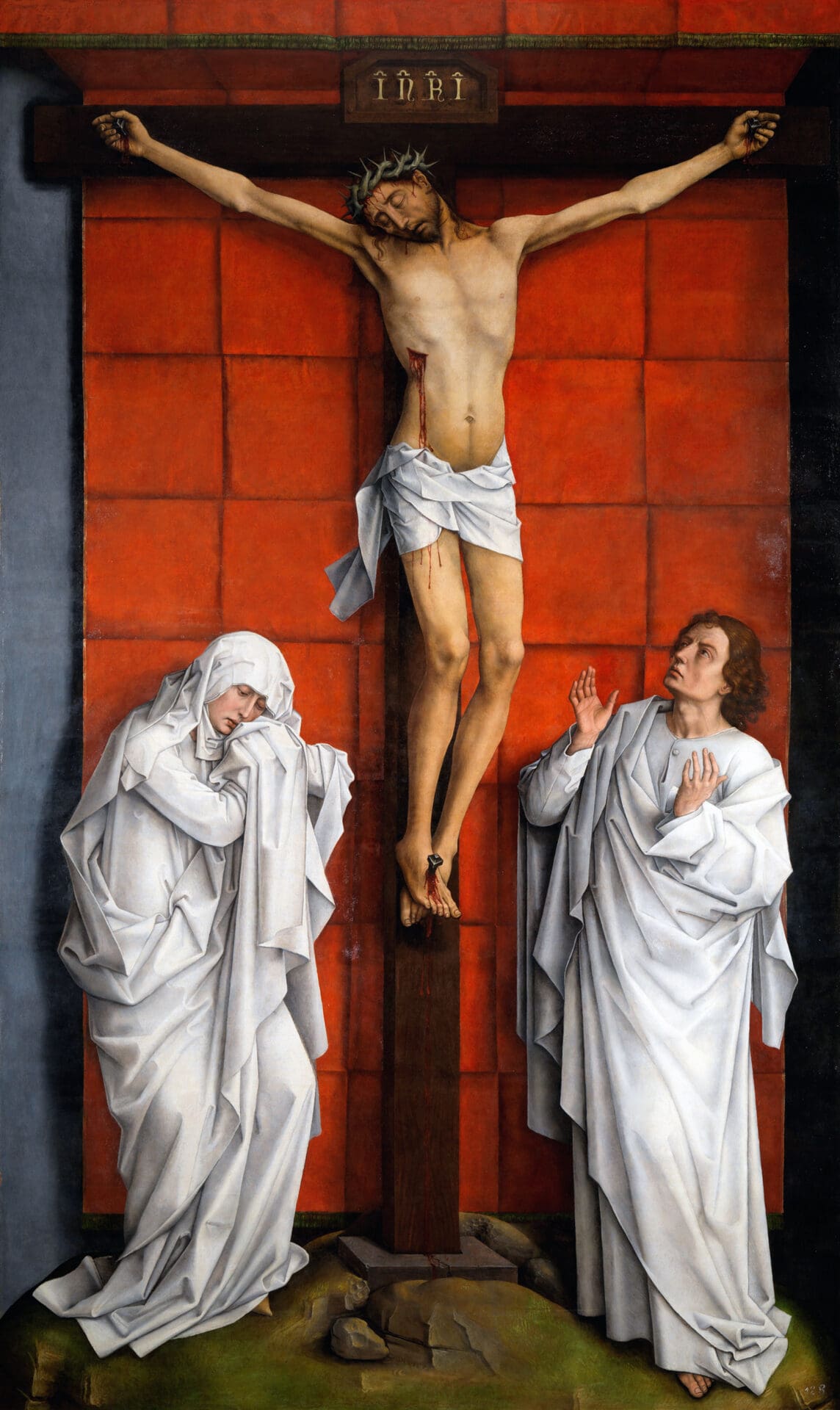

French dramatist Paul Claudel described the dimensions of a church building as “high enough for prayer, wide enough for fraternity, long enough for perspective.”[1] In like manner, any study of liturgy should be wide enough, long enough, far enough, near enough, high enough, and deep enough to touch upon all the horizons that liturgy touches. Here is an image to consider: there are four altars for liturgy—the wood altar of Calvary, the stone altar of the Church, the spiritual altar of our hearts, and the celestial altar in heaven. Christ is at work on all of them; the cross is connected to all of them; the Paschal Mystery is present in each of them, even though one is bloody, one is sacramental, one is interior, and one is supernal.

- Wood altar: Paul interprets “Christ’s death on the cross in terms of the cult…. We are still hardly able to grasp the enormous importance of this step. An event that was in itself profane, the execution of a man by the most cruel and horrible method available, is described as a cosmic liturgy, as tearing open the closed-up heavens (Romans 3:24-26).”[2]

- Stone altar: when the Holy Doors are opened it is “as though they were the gates of heaven itself, and before the eyes of the whole congregation stands the resplendent altar as the dwelling of God’s glory and the supreme seat of learning from which the knowledge of the truth goes out to us and eternal life is proclaimed.”[3]

- Spiritual altar: “In the Church, this power is visible and sacramental; in the soul it is invisible and mystical. I will call the former sacramental liturgy and the latter liturgical mysticism. The former is exterior liturgy, the latter is interior liturgy.”[4]

- Celestial altar: “The river of life can now flow forth from the throne of God and from the throne of the Lamb.”[5]

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia. Head of Christ, by Rembrandt (1606–1669).

Why so many altars? Because Jesus could just not let the Paschal Mystery rest! The reason for multiple altars is the restlessness of divine charity. French Jesuit Jean Grou (1731-1803) explains: “Jesus[,] not contented with a passing sacrifice, the memory of which would soon be effaced from the minds of men, has willed to render the Sacrifice of His Cross ever-abiding in His Church: he willed to find in the contrivances of His Love effectual means to apply its merits to His members in every place and every age: He willed, so to speak, to found His Cross in the Eucharist, and to change it into an inexhaustible Fount, whence the merits of His Precious Blood should be shed abroad everywhere, to vivify, to sanctify His members.”[6] The sacrifice could be offered but once upon the historical, wooden altar, but the whole point of the ecclesial altar is its catholicity and perpetuity. “The Eucharist has, so to speak, this advantage over the Cross, that It is not only the perpetual sacrifice of the Cross, but moreover an inexhaustible source of life.”[7] Although Jesus offered his bleeding sacrifice but once upon the cross, nevertheless his divine ingenuity “found a wondrous means to make it reign in the world until the end of time; He has mysteriously enclosed it in a sacrament of love, where it is made visible, not to our senses, but to our faith…. We behold in the Eucharist Jesus Christ crucified as they sought Him upon Calvary nailed to the cross.”[8]

A Christian loves obedience so much that even abjection can be used to please God.

History Interrupted

The Paschal Mystery has put its foot down in history, but the collect for the Fifth Sunday of Easter prays God to “constantly accomplish the paschal mystery within us.” The crossbeams from Calvary reach as far as every liturgical altar; the visible altar in the Divine Liturgy is the sacramental pathway to the invisible altar in the heart; and this spiritual altar extends to the heavenly and beatific meadow where we will finally be pastured. Indeed, if we wished to name the outer limit of liturgy’s mystery, I would suggest the name deification, which is the purpose of the Incarnation, which, in turn, was the purpose of creation. The reason for the universe is to host eucharists, and the altar is the homestead of deified people.

Image Source: AB/John Ragai on Flickr

Ascetical theologian Charles Louis Gay (1815-1892) describes two acts by God, one interior to the Trinity and one exterior. “God speaks to Himself and gives Himself from within Himself. He has then decreed to speak and to give Himself outside Himself.”[9] When he does the latter, it is by no half measure. “He comes straight to this sum of being, to this treasure of lives, to this abridged universe, which is the nature of man…. His love proceeds at once to do for it His utmost, and thus to carry out for it His first design, which is to make a man-God.”[10] God’s first design is to make a man-God. Jesus is God’s first design. Jesus is the rationale of creation. Jesus is not merely a methodical means to some other end, his hypostatic union is the teleological end of creation. Jesus is the man-God that God’s love proceeded at once to do. And into this man-God liturgists are grafted. “What is Christ? Humanity possessed by the Word. What is each of the Faithful? If faith in him is a living faith, and especially if it is full and perfect, he is also a man possessed and governed by the Word.”[11]

We are talking here about deification, the thing present in liturgy, and the thing liturgical studies should be high enough, wide enough, and long enough to engage.

Jesus—if I may dare the thought—was the first to live the Christian life. A Christian glorifies God; a Christian lives in faith, hope, and love for the Father; a Christian’s life is a sacrifice of praise to God and a sacrifice of charity to his neighbor; a Christian way of life is stamped with humility, and loves obedience so much that even abjection can be used to please God; a Christian should live a holy life, in union with God. By fact of that ineffable union, we may say Jesus is the first Christian. “Jesus, the first Christian, says, ‘I and my Father are One’ (John 10:30).”[12]

Furthermore, Jesus is the first liturgist. Jean Grou writes, “Only an Incarnate Deity is capable of offering to God the adoration due to his Sovereign Majesty. He is worthy of infinite homage, and that no mere mortal can present, because no mortal can communicate to an action a value he does not himself possess…. These essential conditions were admirably combined in the homage of Jesus Christ; he adored in the person of a Man-God; he acknowledged himself indebted to his Father for his human nature, and he consecrated his being irrevocably to the glory of the godhead.” Grou continues: “In this sense it may be asserted that Jesus Christ is the only real adorer, a fact so indisputable that our homage acquires value in the eyes of God only because comprised in and inseparably united to that of His Divine Son.”[13] We are talking here about deification, the thing present in liturgy, and the thing liturgical studies should be high enough, wide enough, and long enough to engage. Lacordaire (1802-1861) observes that “nature is susceptible of that enlargement and transformation which theology does not fear to call deifical.”[14]

Deification happens for the sake of making perfect liturgists.

The Eucharist can be thought of as a divine food that renders the man who feeds on it wholly divine, if he presents no obstacle. The 17th-century ascetic author Jean Baptiste Saint-Jure describes why. “As the hypostatic union of the Divinity with the Humanity constitutes Jesus Christ, so the union of this same Divinity and Humanity with the Christian, makes the Christian in some manner Jesus Christ. Hence, St. Thomas calls this Sacrament an extension of the Incarnation, and, as it is an extension of the infinite communication which the Father makes of Himself to the Son…so the Sacrament of the Eucharist is an extension of the Incarnation for every faithful soul that receives it.”[15] An extension of the Incarnation: a trackway from the hypostatic union, to the Eucharistic altar, to an interior identity, to a beatific fulfillment. In other words, Christ elevates the soul to himself, transforms it, perfects it, and deifies it in himself. Our end is “God and His glory. God has created us to give Himself to us in this life and in the next, and by this means to render us happy here below and in eternity; and to put us in a state to procure Him glory, the last end for which He has created all things.”[16] In short, liturgy lets us experience our end under faith’s veil while waiting for our end to be dis-covered.

Sequential Reflections

This connection between liturgical Eucharist and ascetical deification has long lingered in my mind, and has done so mainly in that sequence. The liturgy is a place of spiritual gracing that is deifical (my thanks to Lacordaire for giving me a form of the word I didn’t have until I read him). Standing before God on a liturgical Mt. Horeb, feeding upon his Son in a liturgical cenacle, and being anointed by the Spirit at a liturgical Jordan are all deifical. The reason for liturgy is deification: liturgy is deification’s efficient cause.

God is satisfied with our worship because it comes from a soul in union with Christ, who is the perfect adorer.

But St. Benedicta Teresa of the Cross (Edith Stein) has just recently added a second way of seeing things. [17] The reason for deification is liturgy: liturgy is deification’s final cause. Deification happens for the sake of making perfect liturgists. She explains what John of the Cross means by supernatural union with God. The soul reflects the divine light in a more excellent way because the will cooperates, which can best be described as a mystical marriage. “The soul receives only in order to give; she gives back to him all the light and all the warmth of love that the Beloved gives to her.” St. Benedicta further notes, “Through a substantial transformation, she has become a shadow of God, and thus [says John of the Cross] ‘she does in God through God whatever he does in her through himself, and in the same manner in which he does it…. She [the soul] perceives here that God belongs to her perfectly, that as his adopted child she has entered into her inheritance with full rights of ownership.’”[18] This is a perichoretic action. The soul, deified, is taken up into Trinitarian giving-receiving that is called perichoresis. The reason for theosis is for man to become a liturgical agent and join the Son, by the power of the Spirit, in his liturgizing the Father. This means the soul does not worship under her own power. The liturgy of the Church is not another one of Adam’s cults, it is the cult of the New Adam mystically perpetuated in us.

And God is satisfied with our worship because it comes from a soul in union with Christ, who is the perfect adorer. “The soul’s deep satisfaction and happiness come from seeing that she can give God more than her own worth and capacity, since she, in such generosity, gives God to himself as her possession.”[19] The mystical liturgist gives God to himself as her own possession. Incredible! Our liturgy has more worth and capacity than we are capable of giving it. God created us, and saved us, and deified us, and gave himself to us, so we can liturgize.

All this has been in the back of my mind ever since my definition of liturgy first presented itself to me: Liturgy is the perichoresis of the Trinity kenotically extended to invite our synergistic ascent into deification. That was my attempt to push liturgical studies to the furthest boundaries of the mystery. Except I should find some way to work in the phrase “hypostatic union.” And, Stein reminds me, the current also flows in the other direction: the extension of the perichoresis is deifical because it invites our synergistic ascent into liturgy. Oh well, back to the drawing board. Something to work on in retirement.

David W. Fagerberg is professor emeritus of Liturgical Theology at the University of Notre Dame. He holds an M.A. from St. John’s University, Collegeville; an S.T.M. from Yale Divinity School; and Ph.D. from Yale University. His books include Theologia Prima (2003), On Liturgical Asceticism (2013), Consecrating the World (2016), Liturgical Mysticism (2019), and Liturgical Dogmatics (2021).

Notes:

- Paul Claudel, The Eye Listens (Port Washington, NY Kennikat Press, 1950) 134↑

- Joseph Ratzinger, “Eucharist and Mission” in Pilgrim Fellowship of Faith (San Francisco: Ignatius press, 2005) 95-96. ↑

- Nikolai Gogol, Meditations on the Divine Liturgy (Jordanville, NY: Holy Trinity Monastery, 1985) 22 ↑

- David Fagerberg, Liturgical Mysticism (Steubenville: Emmaus Academic, 2019) xix. ↑

- Jean Corbon, The Wellspring of Worship (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005) 55. I was tempted to make it six altars, adding two antecedent to the cross. There is, after all, a cosmic liturgy. “The world was created for the sake of the Church” (CCC 760). And the typological altars of Israel are shadows pointing to Christ’s body. “The Church made its appearance in time before Christ did.” (Charles Journet, The Church of the Word Incarnate (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1955) xxvii). But let’s be satisfied with four here, leaving the six as a handy chapter outline for a future monograph. ↑

- Grou, The Practical Science of the Cross (London: Joseph Masters, 1871) 79. ↑

- Ibid., 95. ↑

- Ibid., 59. ↑

- Charles Louis Gay, The Christian Life and Virtues Considered in the Religious State, vol. 1 (London: Burnes & Oates, 1878) 18. ↑

- Ibid., 18-19. ↑

- Ibid., 157. ↑

- Ibid., 51. ↑

- Jean Grou, The Interior of Jesus and Mary (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1893) 368-69. ↑

- Jean-Baptiste Lacordaire, Life: Conferences Delivered at Toulouse (New York: P. O’Shea, 1875) 148. ↑

- Jean Baptiste Saint-Jure, A Treatise on the Knowledge and Love of Our Lord Jesus Christ, vol 1 (New York: P. O’Shea, 1870) 611. ↑

- Jean Baptiste Saint-Jure, The Spiritual Man; or, The Spiritual Life Reduced to its First Principles (London: Burns and Oates, 1878) 196. ↑

- Stein wrote her book on the 400th birthday of John of the Cross, and titled it The Science of the Cross. He was born in 1542; she was arrested by the Gestapo in 1942, while she was in the chapel. It is said that this book was open on the library table when the Nazis arrested her. ↑

- Edith Stein, The Science of the Cross: The Collected Works of Edith Stein VI (Washington, D.C.: 2002) Kindle edition, 228. The quotations from John of the Cross are Stein’s translation; she references that they come from The Living Flame of God, Stanza 3, paragraphs 79-84. ↑

- Ibid., 228-29. ↑

Image Source: AB/Wikimedia. Christus on the Cross with Mary and St John, by Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400–1464).