Editor’s note: In 1923, Guardini wrote an essay called Liturgische Bildung (“Liturgical Formation”); in 1966 (and again in 1992), this same essay was supplemented with other writings and chapters and called Liturgie und Liturgische Bildung (“Liturgy and Liturgical Formation”). Pope Francis references this latter book a number of times in his Apostolic Letter Desidario Desideravi. Until now, Liturgie und Liturgische Bildung has only existed in Italian and German—never in English. But via translator Jan Bentz, publisher Liturgy Training Publications, and support from Adoremus: Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy, a translation of Liturgie und Liturgische Bildung has been prepared and is available starting in September 2022. See www.ltp.org to order.

The new translation of Liturgy and Liturgical Formation will serve generations of priests and laity to discover or deepen their knowledge of the liturgy and how to grow ever deeper in the appreciation of liturgical action.

The Catholic Church, since her earliest days, has had to defend herself against critics accusing her of being hostile to the body and everything carnal. She was thought to be “body-shaming” to take up a neologism popular in today’s culture. On the contrary, in countless examples in art and in doctrine, the Church unfalteringly upheld the unique dignity of the human body—and not just in the most recent body of theology called properly “Theology of the Body.” Nonetheless, this prejudice surfaces time and time again.

A more inquisitive investigation reveals that it was not the Church that appeared hostile to the body, but groups associated with the Church (and eventually identified as heretics) who held exaggerated ideas about mortification and the denigration of man’s worldly existence. Understandably, these excesses of a few could appear to a non-Catholic bystander as general doctrine. One of those groups was the early Gnostics who were among the first to infiltrate and highjack Christian teaching about the body and replace it with a debasing dualism—rooted in vulgar interpretations of Platonism—under the guise of being true, enlightened members of the Church. In consequence, non-Christians easily confused Gnostic teaching with the Christian truth revealed in Genesis in which creation, man, woman, and their bodies were deemed “good” and “very good” by God.

This prejudice still survives today. Take for instance the millions of visitors to the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican each year. On the one hand they gaze in amazement at Michelangelo’s ceiling and “Last Judgment”—and the 351 nudes depicted therein; on the other hand, those unacquainted with Church teaching still persist in their prejudice that the Church despises the body, sex, and everything physical. Naked bodies all around the papal chapel?! But, no, it still does not cast doubt on their presumptions.

Our age like few before seems to suffer from an inherent and ubiquitous dualism of mind and body. Descartes may be considered the most recent culprit of this particular error—it was this Catholic Frenchman who famously gave birth to modern philosophy by splitting man into his irreconcilable dual substances, the soul and what he called “extension”—pure, physical matter. The body was seen as a mechanism, conceived by nature working quite independently of the soul that, in turn, can never penetrate the body. Those in our day who still believe in the soul—or, at the very least, some remaining spiritual dimension of man—will more often than not detach, disengage, and disconnect this spiritual element from the physical body altogether. As a consequence, we see run rampant through the institutions of culture two modern errors: gender-ideology which, ignoring common sense, eviscerates the natural differences between men and women for political gain, and transhumanism—the belief that humanity can achieve a kind of natural immortality, whether through artificial intelligence or anti-aging technology.

Liturgy Embodied

But what does this have to do with the liturgy, one may ask? Isn’t the soul-body relationship something for philosophers and theologians to quibble about? It surely does not have any effect on the practices of quotidian life…

The apparent abolition of the body found within currents of modern philosophy has led to many a change in the liturgical mindset. The Gnostics after all sought spiritual “purity.” The body—along with the sexual urge—was seen as something “dirty,” contaminated, polluted, and tainted. Similarly, the liturgy seems to have undergone an alleged “purification” of all things “superfluous.” In the aftermath of Vatican II, “superfluous repetitions,” “superstitious practices,” “myth-rooted rites,” and other such things were sought to be eliminated to create a purer, simpler, more convenient liturgy, appropriate for the “modern” and “rational” mindset. Man’s life in modernity became ever more “reasonable,” the liturgy in turn became more “practical,” and more “abstract.” Similar to the development in art, the liturgy became “head-heavy,” i.e., cerebral.

It is precisely the liturgy that is the prime locus in which the body-soul unity, an essential element of Catholic anthropology, is manifest and truly comes into its own.

Yet, it is precisely the liturgy that is the prime locus in which the body-soul unity, an essential element of Catholic anthropology, is manifest and truly comes into its own. In the worship of God, man has to participate with his whole self, body and soul, not as separate elements but as a harmonized whole.

One author as few others was spearheading the counterattack of the body-soul dualism and steering towards a renewed understanding of the unity of man in body and soul. That man was Romano Guardini. His writings, now more than a hundred years old, have lost none of their piercing insightfulness, forthwith criticism of liturgical deviations, and traditional Catholic thinking which sought to effectively upend the philosophical underpinnings of reductionist convictions. Even as a child of his time—with all the unavoidable pitfalls that the 20th century brought—Guardini remains to this day a source of profound insights about the liturgical being that is man.

In Liturgy and Liturgical Formation, translated by this writer for the first time into English, Guardini shows why the body-soul unity is crucial for Christian anthropology and, even more importantly, why the fragmentation of body and soul have dealt a deep wound to the liturgy. A fragmented being fragmented the liturgy, says Guardini who, at times writing in witty prose, demonstrates his unbroken intention to call for a return to an authentic celebration of the liturgy, body and soul, through a greater internalization and participation in the Church’s sacred rites.

For Guardini the most important “symbol” (different from allegory which connects arbitrary signs to meanings) is precisely the soul-body relationship.

Guardini’s arguments concentrate on one crucial point: precisely because man is not a pure spirit, an angelic being, his actions in turn cannot be of a purely spiritual sort. There exists a peculiar unity between the soul and the body, between spirit and matter. Whatever moves the spirit will move matter, and concomitantly whatever affects matter will somehow also influence the spirit. Human nature’s existence is such.

“Man as a whole bears Christian devotion,” Guardini writes. “It is not a ‘purely spiritual’ devotion—what this could look like we do not know. We are not pure spirits, we were not supposed to be, and not even the battle against the body, which is imbued with a desire for freedom, should fool us into thinking this.”

Here Guardini reveals his profound adherence to the perennial doctrine that the human person is “very good”—body and soul. Surpassing every Gnostic reduction, he insists that it is precisely the body that is a crucial element of the liturgy. Prayer in its most perfect state is not just cerebral, it is acted out, it is lived.

Informed Consent

The mystery is deep indeed, a “stumbling block” if you will, but ultimately the very reason why the Church—in liturgy and other areas of the faith—has always made room for man in his dual but unified dimension. The ultimate appraisal of the body is found in the Christian mystery of the Incarnation. The very essence of the Church herself is linked with this mystery: she—as a visible institution—administers the sacraments (material signs!) in order to save man, body and soul. The doctrine of the “resurrection of the flesh” also emphasizes this. And this physical element is certainly crucial for the liturgy. For Guardini the most important “symbol” (different from allegory which connects arbitrary signs to meanings) is precisely the soul-body relationship.

“The human body is the analogy of the soul in the sensible-bodily order,” he writes. “If one were to express the soul, which is spiritual, in a bodily fashion, then the result would be the human body. This is, in the strictest sense, the meaning of the formula, anima forma corporis” [the soul is the form of the body].

And thus man must embrace his dual reality to encounter the center of the liturgy, which is Christ, who himself possesses a human body. Herein lies the first and most basic challenge of liturgical formation: man must become capable of symbol, or said differently, man must learn how to establish unison between his spirit and his body. Whatever the soul is to enact (worship, glorification, contrition, penitence, etc.) the body needs to mirror. And whatever the body does will either drag the soul down or raise the soul up.

Herein lies the first and most basic challenge of liturgical formation: man must become capable of symbol, or said differently, man must learn how to establish unison between his spirit and his body.

Guardini decries the progressive loss of this sense since the Middle Ages, as the natural bond of the material and the spiritual has gradually been loosened. “This loosening did not grow out of some kind of asceticism,” Guardini notes. “Genuine asceticism does not want to destroy the body or estrange the soul from it, but wants to bring the body always more under the formative power of the soul. In asceticism, the true relation within man is re-established, and thus the body is continually more spiritualized. What began in modernity is something completely different. Modernity strives for a ‘pure’ spiritual being, affecting one of the most terrible confusions that have ever plagued the dissent from an integral understanding of man: the purely spiritual was sought and it resulted in something abstract. Embodiment, and therefore symbol too, were discarded. Almost imperceptibly, the abstract took the place of the spiritual, the pure concept.”

In seeking this unattainable and illusory purity, man has demolished the natural unity of body and spirit—or at least he lives in the constant illusion that he has. With Guardini, we witness countless outgrowths of this base dualism, including what was noted above, utopian transhumanism and unimaginable gender-ideology.

Heart of the Matter

The last 50 years or so have seen a rampant impoverishment of culture and, with it, the rise of a new paganism and the complete disintegration of the human person. As a result, the liturgy has suffered. Instead of offering to man the perennial image of Christ in his body and soul, sacred art has become abstract, liturgical action has become “pastoral” (read: it seeks out to be as mundane as possible in the hope to offer more “accessibility”), and the whole mindset of the liturgy has become minimalist. The central conviction of many pastors does not seem to be: “How can we give the most glory to God in the most perfect way?” but rather: “What are the basic, essential requirements that we have to obey in order to remain valid?” Holy cards are smirked upon as sanctimonious, incense is an irritating addition, beautifully adorned vestments are “pompous,” well-crafted, plastic art is shrugged off as “triumphalist,” etc. Gold makes way for tin, brocade makes way for polyester, kneeling adoration makes way for sentimental community-feeling—the examples are countless.

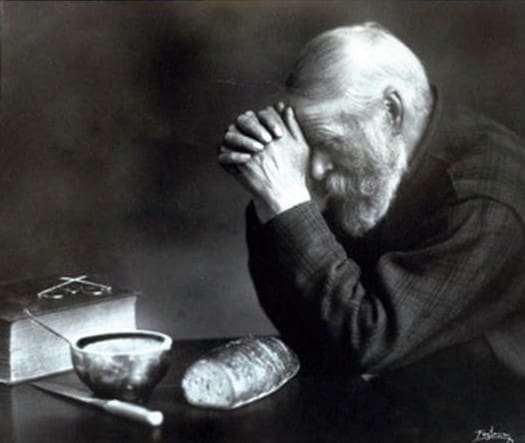

“We must learn to pray with the body,” comments Guardini soberly. “The posture of the body, our gestures, and our actions must become directly religious once more. We must learn to express interiority in our outward appearance and to read the internal by the external.”

But how should this be learned? Guardini’s work employs more than one pedagogical tactic to regain the sense for this unity. The learning process begins not in the liturgy—ultimately the moment of implementation—but before the liturgy. Guardini suggests starting at the earliest age, indeed in the teaching of children. Educators should imbue a natural sense of movement and action to children, aiding them to embrace their actions fully. Gestures, movements, expressions, postures: these must all be properly learned. Indeed, by learning ritual and intentional movement in the actions of daily life, the child will, as a consequence, have the proper disposition to approach religious actions in a state of readiness and with openness to understanding. Thus when the child reaches the age of understanding, his or her pedagogical introduction to liturgy will yield immediate fruit. As an example, Guardini observes: “When a mother takes her child into the church at the right hour, walks slowly up the stairs into the church and says, ‘Now we climb up…up into the church…to God,’ then the child will correlate the bodily climbing with the spiritual ascension to God.”

Just as grace requires and builds on nature without destroying it, so liturgical action requires human action, informed and ensouled. Man has to learn how to behave before he can behave in a sacred way.

Each moment of life gives a different occasion for proper movement: breakfast at the family table, a ball-room dance, or a stroll in the park—all are naturally arising occasions for different movements. The liturgy in its own right demands a certain type of gesture, posture, and movement, first and foremost in the celebrant, but also in the faithful.

The unity of body and soul and its significance for the liturgy are not exhausted here. The body naturally seeks to extend its action into the surrounding world and its tools and artifacts. Thus, Guardini: “The performing hand’s expression is expanded when it holds a bowl; the power of a punch is strengthened when a hammer is held.” Consequently, man transforms the whole space around him by his actions. In everyday life a home is formed as the result of things taking on, by human acts, certain human characteristics. This is the place where man makes everything his own.

The sacred space has to be ordered similarly. All things, instruments, vestments, even elements such as water and fire, are put in the service of transcendence, of God himself. Mass cannot be celebrated without instruments; so tools are imbued with a higher meaning and as such are elevated from being profane to being sacred. A bowl ceases to be a bowl in the liturgy, and the tongues of the communion bells cease to be mere hammers chiming against metal. Likewise, natural elements such as water—which certainly can be destructive—are purified and put at the service of God and life-giving sacramental actions. In this way, water becomes a symbol of purity, but one which truly does what it says both literally and figuratively—it purifies both body and soul. For this reason it is an indispensable part of the sacrament of Baptism. All things—even material things—are thus ordered towards God.

This sacred ordering then “spills over” into everyday life. While the liturgy is the cornerstone of the week, the liturgical calendar demands that man form his life with respect to it. There are times of fasting, penance, preparation, and special prayer, alongside feasts, celebrations, and moments which offer opportunities to receive intense spiritual power. Most countries in the West still today honor Christian feasts—so the power of transformation has (until very recently) successfully and without interruption informed the spiritual foundation and moral fiber of our nation and our culture. We can recall the image of a cathedral being the center of a medieval village, and the altar being the core of the cathedral. Symbolically the village developed around this core and progressed ever outwardly to expand and bring the Gospel’s central message further into the “savage” and “barbaric” world.

Everyday Holiness

Guardini convinces the reader with such local, physical considerations—and their universal possibilities—that the liturgy and liturgical action have the utmost significance. Having profoundly penetrated the mystery of the Christian cult, Guardini is able to communicate its central elements to the common man with numerous examples from everyday life always with a practical application in mind. Countless are the lessons learned from this great German theologian and liturgist, and they are more relevant than ever.

In a time where everything is homogenized, boiled down to the lowest, blandest common denominator, massified and secularized, Guardini provides a welcome antidote in his refreshing insights into the true and real fruits of the liturgy. Every generation must learn anew how to be liturgical, how to order oneself—body and spirit—towards God and how, in turn, to transform the world into a sacred place.

St. Paul says that through Christ we are all called to incessant prayer (I Thessalonians 5:17). Likewise, our whole life must consistently and continually reflect the truths of Christian revelation. And the Church has given her children manifold ways to reflect upon her essential core truths: the liturgical year, feasts so essential for the human being, liturgical space, architecture, sacred art, chant, music, art, paintings, gestures, rituals, rites. The list is endless.

What Guardini touches on is the perfect unison of the profane and the sacred, the bodily and spiritual, which—paradoxically—become one in the act of worship, placed at the service of God, transfigured into their most perfect use and finality.

Just as grace requires and builds on nature without destroying it, so liturgical action requires human action, informed and ensouled. Man has to learn how to behave before he can behave in a sacred way. Man must learn how to use instruments before he can learn how to use instruments in a liturgical context. And man must learn how to think well before he can pray properly. Our time craves form, order, authenticity, and leadership—and while it is disintegrated and destroyed everywhere else, the prime location for its most human and transcendent manifestation is the liturgy.

Chapters in Life

Guardini’s thoughts are by far not exhausted with this little presentation. His meditations in Liturgy and Liturgical Formation stretch far over liturgical prayer, time and its relation to space, eternity, formation, education, beauty, religion, mysteries, man’s relation to himself, to God, and to the community, and the challenges of modern man.

While not always simple or easy to read, Guardini utilizes a pedagogical style which forms the reader while he tries to understand the thoughts and insight of the author. Every paragraph is a meditation, every chapter a life-lesson. Guardini succeeds in expounding difficult subjects with clarity, precision, and lucidity, and he guides the reader faithfully through complex matters with fitting examples and immediate applications which clergy and laity alike may find fruitful in their encounter with Christ in the liturgy and in their daily lives.

The new translation of Liturgy and Liturgical Formation will serve generations of priests and laity to discover or deepen their knowledge of the liturgy and how to grow ever deeper in the appreciation of liturgical action.

Jan Bentz was born and raised in Germany and graduated high school in St. Louis, MO, after studying as a foreign exchange student. Prof. Bentz studied philosophy, Church and religions, and Sacred Art and Architecture in Rome. After teaching in Rome he has moved to Oxford where he is a lecturer and tutor in philosophy at the Studium of Blackfriars. In his journalism career he has contributed video productions for EWTN, and his contributions have been published by Inside the Vatican, The Catholic Herald, Catholic News Agency, and Jüdische Rundschau. Prof. Bentz also worked as a docent tour guide in Rome and the Vatican.