The Order of the Dedication of a Church, the liturgical book containing the prayers used to place a new church into liturgical service, calls the church building “a special sign of the pilgrim Church on earth and an image of the Church dwelling in heaven” (Order of the Dedication of a Church (ODC), Introduction, 2). While this may seem surprising to people used to the plain churches built in recent decades, the Church’s liturgical books repeat the theological point that a church building is an image of Christ himself, “the true and perfect temple,” composed of “living stones” (ODC, 1). Therefore, a church building, composed of many properly arranged architectural members, signifies the hierarchically arranged membership of the Body of Christ.

And so the ODC makes the clear claim that the name “church” is “rightly” given to the building in which the Church assembles and unites itself with the Church in heaven (ODC, 1).

The history of the Church shows how varying cultures imagined the unity of heaven and earth in liturgical art and architecture, from the great mosaics of the Roman basilicas to the angel-filled stained glass windows of the Middle Ages, up to the style revivals of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Frequently, these sacred images show creation as it will exist after the end of time, when the fallen world is restored, and God, man, and nature are united and glorified. The advent of architectural modernism in the second half of the 20th century combined with a low “house church” model of liturgy in the 1980s and 90s led to the virtual disappearance of the great murals and mosaics revealing the heavenly dimension of worship. In recent years, however, clerics, scholars, artists, architects, and the faithful have called for a rediscovery of the liturgical image in conjunction with today’s renewal of traditional architecture.

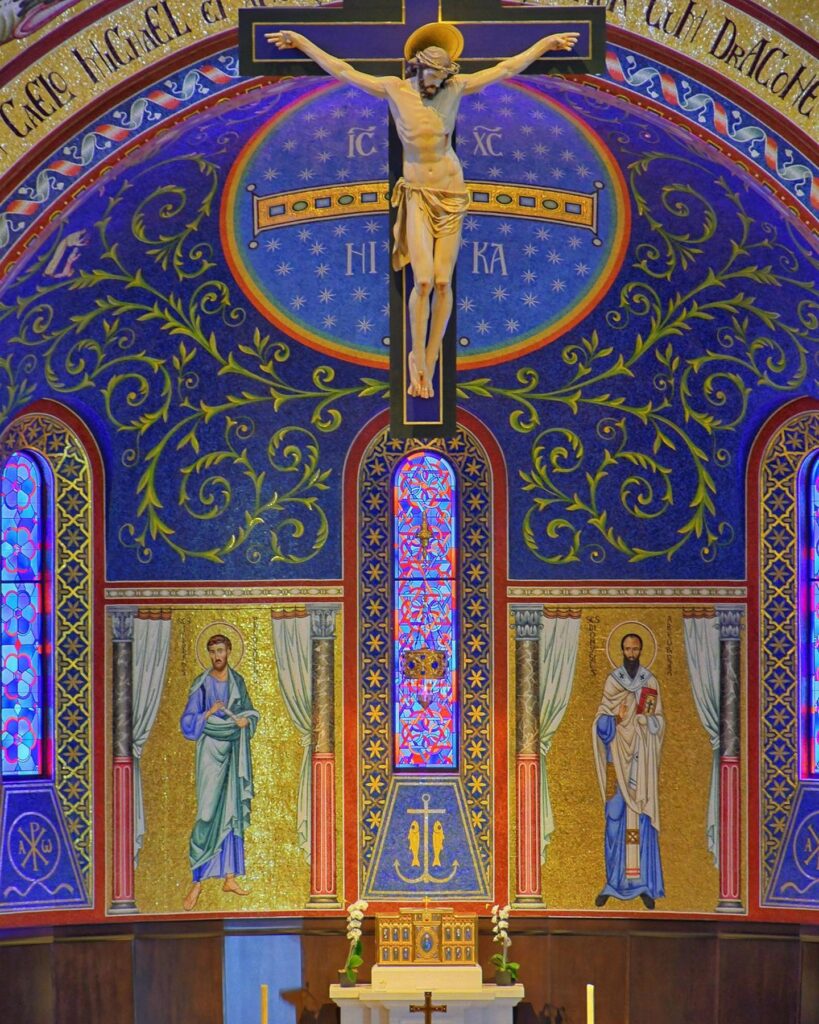

In line with the great tradition, an elaborate set of new mosaics now crowns the east wall Church of Our Lady of the Assumption, part of the new St. Michael’s Abbey, completed in 2021 by the Norbertine Canons of Orange County, CA. Enzo Selvaggi of Heritage Liturgical served as creative director for the chapel project, developing the iconographic plan together with the Norbertines, designing not only the east wall mosaics, but also the abbey crucifix, imagery in the side shrines, statuary, and liturgical items. Selvaggi likewise guided and worked together with artisans, including Italian iconographer Giovanni Raffa, mosaicist Valerio Lenarduzzi, and sculptor Edwin Gonzalez.

From the beginning, the particular artistic mode or “style” was chosen to be iconic without being singularly Eastern. Rather, the design began with the highly developed Italian tradition of iconography found in great mosaic works of the Roman basilicas and the churches of Ravenna, establishing the chapel’s mosaics as distinctly part of the Western artistic tradition. With softer, fleshier bodies and more naturalistic representation than the strict Eastern iconic tradition, the images were meant to be recognizable to Western Christians living today.

Mary: Front and Center

As the central visual feature of a chapel dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption, the mosaic centers on the Blessed Virgin’s favor of being taken, body and soul, into the glories of heaven. But it was designed to bring forth the Virgin’s other attributes as well as her larger role in salvation history. As she rises, for instance, she receives a crown from Christ’s hand, referencing her coronation. But her placement atop a crescent moon with a background of 12 stars makes her the Woman of Revelation, doing battle for the redemption of the world. Surrounded by seraphim, she appears clothed with the sun, crushing the serpent, an idea generated by the Latin text from Revelation 12:1 which runs along the top arch: “a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.”

While the mosaic rightly displays the Virgin’s supernatural peace in the golden background of heaven, the scene reveals both the perfect calm of God’s eternal victory and the drama of a temporal battle. The Virgin’s role in this fight is highlighted by the two archangels who appear with her. To the Virgin’s left appears St. Gabriel, who opened the first chapter of her life as Mother of God at the Annunciation, beginning her role in destroying Satan’s power by her fiat to the Incarnation. St. Michael, the patron saint of the abbey, appears at the Virgin’s right, slaying the serpent. Though Michael is often seen alone as a heroic dragon-slayer, this mosaic indicates that the Virgin crushed Satan’s head by cooperating with God’s plan in bringing forth the Savior. Only because of her yes to God’s plan can Michael finish the work. In doing so, he highlights her role as the New Eve. As the first Eve was deceived by the serpent and brought death to humanity, so the New Eve defeats the serpent and brings eternal life through her Son. Together, Gabriel and Michael visually bookend the Virgin just as each mark her role in Christ’s mission of salvation. Accordingly, the serpent’s tail wraps behind its body and appears under the Virgin’s feet, indicating that the chaos of evil indeed penetrates creation and cannot be denied, yet it is crushed by her feet and faces the spear of St. Michael in its mouth.

Begin at the End

The eschatological nature of the event is further elaborated by a horizon line composed of circles which divide the mosaic into two zones: heaven above and earth below. Each disk illustrates one of the seven plagues mentioned in chapter 16 of the Book of Revelation, the punishment on the unrighteous. Because the plagues herald the Second Coming of Christ, this moment in the life of the Virgin also portends the Last Judgement. Accordingly, the lower left side of the outer mosaic shows an angel blowing his trumpet (Revelation 8-12), unrolling a new sky over the saved who rise from their graves. In the lower right, another angel leads the souls of the saved to heaven and shows the damned in hell. In this way, Christ is present in everything as final Judge, even as the mosaic highlights the central role he gave to his Mother.

The smaller arch below, visually supported on two stylized Corinthian columns, offers a quote from the Book of Revelation 12:7: “and there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon.” This phrase not only refers to the abbey’s patron, but to the mosaic’s larger eschatological theme as well, since it is the last sentence in scripture before the dragon is cast out of heaven and his losing battle with the Woman begins. The faces of the apostles appear on the underside of the curve, symbolically indicating the victorious living stones of the arch itself. Beneath them, great flowering shrubs appear like columns, bearing figs, pomegranates, pears, and lilies, revealing the abundance of the New Garden which is the earth itself at the end of time. The arch is also ornamented with stylized ribbons and jewelry-like stylized gems, indicating the joy of heaven as the Wedding Feast of the Lamb.

Through the arch appears a vision of the new Earth joined to the new heaven, most clearly articulated by the great spiraling vine on a background of deep cosmic blue. Inspired by early Christian images such as the great Tree of Life at San Clemente Church in Rome, the spiraling plant springing from a single point at once signifies Christ as the Vine and the new tree which succeeds the tree of Eden, the cause of mankind’s Fall. On the left side amidst the vine appears a small figural image portraying a Norbertine canon tending the vine and cutting fruit for a woman with a basket below. Added to honor a donor who sponsored the mosaic, it speaks of the laity tending the vine of the Church together with clergy, and reaping fruit for God in the spiritual realm. This is indicated by the eighth circle on the wall, an image of Christ the Lamb in the Heavenly Jerusalem, rightly signifying the “eighth day,” or the day of eternity.

Signs and Symbols of Victory

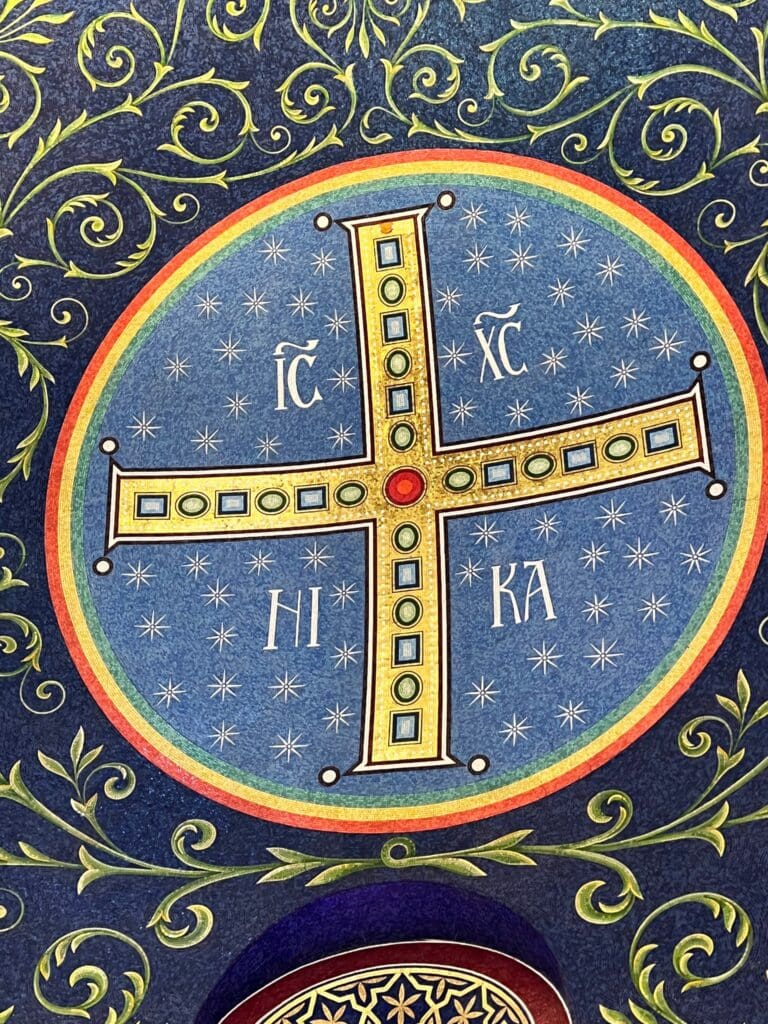

Centered amidst the vine appears a great rainbow-edged circle, filled with stars and a crux gemmata, or jeweled cross, an early Christian method of representing the victory and kingship of Christ before the Church had begun the custom of representing Christ’s body upon the cross. The stars indicate Christ’s cosmic victory and heavenly power, while the rainbow speaks of the restored relationship between God and humanity, given as a sign to Noah at the end of the flood and present at Christ’s throne in heaven (Revelation 4:3). In the four quadrants behind the cross appear the traditional Greek acronym, ICXC NIKA, or “Jesus Christ Conquers,” a veiled reference to the Virgin, through whom Christ defeats sin and death. This cross works together with the crucifix hanging over the altar of sacrifice, which bears the figure of Christ. While it may appear more familiar to Western eyes, it clearly places Christ in the eternal setting, as it reads Rex Gloriae, or “King of Glory,” above Christ’s head. And in a nod to the unity of Eastern and Western Christianity evident in the mosaics themselves, Christ’s hands bless in the Eastern gesture on one side and Western on the other.

At the lowest level of the mosaic appear four priestly figures from scripture and early Christianity: Abel, Aaron, Dionysius the Areopagite, and Justin Martyr. Abel, Eve’s second son, offered proper sacrifice and yet was murdered by Cain, making him a martyr and a prefiguration of Christ, bringing him mention by name in the Roman Canon with Abraham and Melchizedek. Aaron, the brother of Moses, was given the task of leading the Old Testament priesthood, while Dionysius became the first bishop of Athens after hearing the preaching of St. Paul. Lastly, Justin Martyr, the second-century Greek philosopher-convert, wrote in his Apology one of the most important and clear descriptions of the sacrifice of the Mass in 155 AD. Each of the priest figures appears as through an open curtain, recalling the veil of the Temple and the border of heaven and earth, establishing them as figures in heaven.

As a whole, the mosaic program at St. Michael’s Abbey marks a true high point in the renewal of liturgical imagery for the Western Church. More than a mere assemblage of pious pictures, it forms a layered whole rooted in scripture and salvation history. Though centered on the Assumption, the overall grouping shows the final victory of Christ through Our Lady, together with the angels and saints. This theological idea works beautifully with its tangible expression in the art of the mosaic. Christ’s Mystical Body, the Church, continues his work in the world through its members. When these members work together—that is, assemble hierarchically under Christ—their varying gifts and vocations form an image of Christ in the world as priests, prophets, preachers, teachers, and healers in an anticipation of heavenly glory; they are living stones in the temple of God’s Presence on earth.

By way of analogy, a similar thing can be said of the mosaic. Made of millions of tiny pieces of stone and glass called tesserae, a mosaic only becomes legible, and therefore only reveals the mysteries of Christ, when properly cut and assembled. Moreover, the gemlike colors, stylized perfection of the figures, and shimmering gold not only show the glory of heaven in an intellectual way, but capture its reality and allow participation in its reality. In this way, the mosaics of St. Michael’s Abbey fulfill the request of the Second Vatican Council that sacred art be composed of “signs and symbols of heavenly realities” (SC, 123) that allow more complete and active participation in the sacred liturgy as source and summit of the Christian life.

Dr. Denis McNamara is Associate Professor and Executive Director of the Center for Beauty and Culture at Benedictine College in Atchison, KS, and cohost of the award-winning podcast, “The Liturgy Guys.”