We need not be town planners to know that there is normally much more life and color in the centers of our cities than on the fringes. This simple principle was just as evident in the great cities of the ancient world.

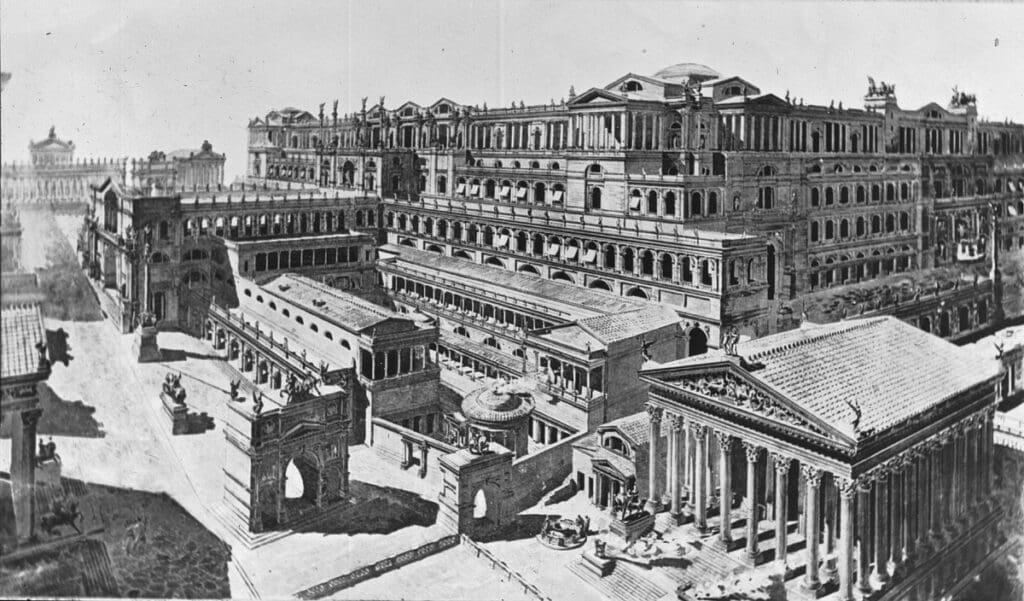

Thebes, a major ancient Egyptian city at the time of Moses, clustered something like 80,000 people around a center rich in beautiful temples and enormous royal mausoleums. Nineveh, capital of the Neo-Assyrian empire and at one time the largest city in the world with 150,000 residents, ringed the “Palace Without Rival,” the famous Southwest Palace, constructed in the eighth century without regard for cost to celebrate in spectacular style the self-declared magnificence of King Sennacherib. And of course there was Rome, itself the hub of a vast empire, which had at its center the Forum Romanum: the locus of advanced government, spectacular triumphal processions, stadiums for gladiatorial combat, temples, chariot races, shrines, and the busiest marketplace of the ancient world. In a world of rough stone and timber, Rome was gold and smooth marble, with five aqueducts delivering more fresh water to the center of the city than New York would receive from its water sources in the 1980s.

Great ancient cities were not the unbridled chaos we imagine them to have been. And everyone in them—the citizens and the planners—understood the importance of the city center. The centers set the tone. Centers made statements about the powers and residents as much as they hosted various civic functions.

It should not surprise us that St. Augustine, one of the most sophisticated intellects of the ancient world, found volumes’ worth of inspiration in the sophisticated urbanism of his era. In his early-fifth-century masterpiece, The City of God, Augustine explored in particular the idea of cities as models of human society. Broadly speaking, he argued there were two different types of society: the earthly city, or the City of Man—whose citizens worshiped themselves and their fleeting, base desires—and the heavenly city, or the City of God—where people worship Christ and seek to honor him. Crucially for our purposes here, Augustine stresses that differences between the City of Man and the City of God arise because of fundamental differences in the objects at their centers. “God is in the midst of her,” writes Augustine of the holy city in Book II, Chapter 1. At the center of its earthly counterpart are the false pagan gods, the gods of the self who, “reduced to a kind of poverty-stricken power, eagerly grasp at their own private privileges, and seek divine honors from their deluded subjects.” Just like the centers of physical cities, these metaphysical centers set the tone for their metaphysical surroundings.

One Way Ave.

A society centered on the self is inherently miserable and ultimately doomed. There is no street in the earthly city that can lead to a redeeming destination. In the end there is only the profane core, rendering all the boulevards and bridges around it worthless.

How this image contrasts with that of Augustine’s heavenly city, where the Lord is at the center, and it is Scripture, prayer, saintly example, and divine inspiration that form the streets that lead us to him. Dom Bede Griffths, the 20th-century English scholar and monk, offers a description of monastic life in terms that could apply perfectly to Augustine’s heavenly city: “The governing principle of the monastic life is that nothing is profane. One serves God just as much when taking a meal or working or studying as when chanting the Office in choir. In this way the whole day is given a sacred character, which influences every activity.”

A society centered on the self is inherently miserable and ultimately doomed. There is no street in the earthly city that can lead to a redeeming destination.

Here, Griffiths is also saying the object at the center—the object of our worship—colors everything. If the center is good, so is the city. “In this vision of life there is nothing which is not holy,” he continues. “The simplest actions of eating and drinking, of washing and cleaning, of walking and sitting, of lying down and rising from rest, have a sacramental character; they signify something beyond themselves and are intimately related to religious rites.”

We need not possess the talents of architects or scholar-monks to see this principle of “the sacred center” applied to the design of our churches, too, where the heart of each church is an altar: a place of sacrifice, where the bread and wine, and even the faithful themselves, are transformed. Properly understood, a church is actually built around its altar the same way Augustine’s heavenly city is built around Christ, and, properly executed, the fabric of the church is a liturgy that concentrates our attention like a network of streets with one inevitable destination.

In this sense, the mosaics, tapestries, and stained glass of a church will never be simple decorations. They are sacred images. By these means we raise our minds to the divine mysteries. The same is true of the Order of the Mass, which leads us step by step from our mundane starting point just outside the building to the triumph of the Eucharist. It is equally true of the readings, the music, our prayers, and everything else forming the work of the Mass.

A confused culture is capable of worshiping the wrong objects with the worst sort of religious fervor, unleashing on those deemed to be unbelievers a scourge of inquisitions, punishments, shaming, and banishments.

Are there equivalents to this in the earthly city? Augustine sees none. As mentioned, its streets have no destination but the self, and they are dead ends. At no stage does Augustine labor the metaphor of city streets, but he describes in vivid detail the effects of being trapped on them. How lost, restless, and desperate the citizens are! Griffiths sees similar desperation and futility in the profane city, though he puts it in 20th-century terms when he describes the plight of workers in a strictly secular world: “the laborer feels himself to be the slave of a system for which he has no respect. It is only when the work is done for God, as part of man’s co-operation in the divine plan, that its hardships and inevitable conflicts and frustration can be endured, and the workman can feel himself to be sharing in the labor and the suffering of Christ.”

Rough Rd.

Perhaps we could, in the spirit of the secular, consider for a moment the concept of liturgy outside its sacred context and define it more generally as “the practice of shaping our love.” Liturgies in this sense are very common in the earthly city. Think of shopping centers, football games, rock concerts and movies, and all of the excitement, sensuality, and material prosperity associated with them. In a consumer society centered on the self, these profane liturgies do the work of capturing our imaginations, co-opting our hearts’ longings, and, to quote Charles Taylor, author of The Secular Age, training us “to love the right things the right way.” (Except that, of course, if an object of our love—the shopping center, the football game, etc.—does not ultimately lead us to God, it is to love the wrong things in the wrong way.)

The power of these social, secular liturgies should not be underestimated. If they are each a network of streets, then the streets themselves are smooth-paved, tree-lined, artfully lit, innumerable, and thronging with irresistibly attractive contemporaries, whatever the destination they serve. Some argue that these liturgies are precisely what draw people away from traditional, institutional religion. As Taylor observes, the success of consumer culture against religion may be attributed to “the stronger form of magic found in the ever-new glow of consumer products.” Many of our contemporaries know no other kinds of liturgies and it should not surprise us to see the streets of the earthly city are so full.

If anything, we should react with sympathy. None of us is wholly immune to the lure of the secular sirens seducing us into forgetting about God, especially when they call to us with voices especially pitched to resonate with our egos. We should lament more how easily we are distracted from God! The secular, social liturgies are very powerful here. Consumer culture caters superficially to practically every aspect of the self, which is by definition intensely distracting. Resting from and sorting through the barrage of consumer messages takes time, energy, and a conscience that is sometimes insufficiently robust. Consumer liturgies are particularly effective at distracting from what haunts us especially. Tedium and ennui are at the terminus of every cul-de-sac we wander into. These demons haunt us when we weary of our routines, or when the excitement of the movie dissolves, when the car is no longer brand new, or during the off-season of our favorite sport.

Wrong Turn Ln.

Deprived of sacred liturgies to orientate it towards Christ, and haunted by a lack it cannot name, a culture orbiting the self will inevitably approach the wrong objects as though they are sacred, attaching to them an eternal significance. A confused culture is capable of worshiping the wrong objects with the worst sort of religious fervor, unleashing on those deemed to be unbelievers a scourge of inquisitions, punishments, shaming, and banishments. Observers of the politics of “climate change” and “social justice” will see these themes at work repeatedly. Once more, we should not be so amazed, even if we are distressed to see the sacred inverted in this manner. Worship of the wrong object is an idea as old as the story of the serpent in the garden, and it is for good reason that the very first of the Ten Commandments directs us to have no other gods but God. There is much to be gained from acknowledging that it is more or less guaranteed in a society that has torn down all the pointers to the sacred. We can make a solid start to finding the right streets to God by seeking direction from secular culture less often than mankind currently does.

It is no accident that much of the most beautiful art and music in the Western tradition has been religious, and that a good deal of that has been produced for use in the sacred liturgy.

Readers will know intuitively the ugliness of modern cities. It is always the artisan-built, older places like Barcelona, Venice, and Buenos Aires that dominate the Top Ten lists of seasoned travellers. With their colorful, human-scale buildings and their lively public squares, these cities compare very favorably to more modern cities. Who can find joy in the flatness of the glass and concrete towers in the central business districts, the monotonous soulnessness of chain-stores, fast-food restaurants and other quick-build edifices in the suburbs, and the poisonous aesthetics of freeways snarling with cars? These poor fruits of today’s culture produce nothing but a depressing effect on our spirits. Modern town planners try hard with codes and incentives, but only a few succeed in coaxing lasting, real and uplifting beauty from these developments. We respond to beauty, and we feel its absence keenly.

Heaven Blvd.

It is no accident that much of the most beautiful art and music in the Western tradition has been religious, and that a good deal of that has been produced for use in the sacred liturgy. Not all of this art and music is as lavish or as expensive to produce as we might assume. Gregorian chant, for example, emerged gradually as a form of worship from monasteries in materially impoverished, post-Roman Europe, requiring no instruments, no wealthy patrons, nothing other than human voices and the love of God.

Griffiths writes movingly of the special kind of beauty he sees in liturgical art and music—it is art and music that bring heaven to earth, and earth to heaven, by a power far beyond themselves. Here the arts exercise their highest function. Griffiths writes: “In the architecture of the church, the sculpture and painting on the walls, the music of the chant and the color and shape of the vestments and the hangings on the altar, the solemn and rhythmic ceremonies of the choir and sanctuary show forth the mystery of the divine Word; to manifest it not only in abstract terms to the reason only, but in its concrete embodiment, appealing to eye and ear, to sense and imagination, to heart and soul.”

Sacred liturgy forms the finest streets we have in the City of God.

“Yet all this outward splendour is strictly subordinated to its end,” he continues, “which is to enable the soul to pass through its outward form to its inner meaning, to contemplate the Word of God, to be moved by the action of the Holy Spirit.” In these terms, the artisan in the City of God has much to celebrate. So fortunate he is in comparison to the laborer mentioned earlier, whose work is without meaning!

Sacred liturgy forms the finest streets we have in the City of God. On these streets our souls are built and shaped, and our attention is directed away from the many distractions of this world to Christ. By the liturgy our inadequate overtures towards Almighty God are redeemed. And at the altar to which we are led, and where we share in the life, death, and eternal life of Jesus Christ, so are we.

William Schaefer worked on farms, drilling rigs, and building sites before finishing an honors degree in history and ancient history at the University of Western Australia (WA), Crawley, WA, in 2004, and a Masters of Urban Planning at Curtin University, Bentley, WA, in 2013. He lives with his wife and two daughters in Perth, WA, where he works as a town planner.

Cover Image Source: AB/Wikimedia