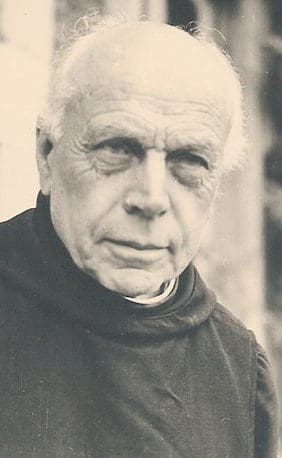

In 1915, just before being called to a military chaplaincy in the First World War, Jesuit theologian Maurice de la Taille placed in the hands of the publisher a three-volume work which constituted the fruit of 10 years of research and writing on the Eucharist: Mysterium Fidei: de augustissimo corporis et sanguinis Christi sacrificio atque sacramento, Elucidationes L in tres libros distinctae (The Mystery of Faith: Regarding the Most August Sacrifice and Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ, Fifty Elucidations in Three Distinct Books). Beauchesne released the book six years later, in 1921. De la Taille purportedly told the publisher that he did not expect the book to sell more than 30 copies worldwide; by 1931, sales had reached over 3,000 and a third edition was at the press. The author himself was likely among those most surprised.

Yet the book—and its author—remain to this day important components of the liturgical movement. To understand why, let us first look at De la Taille’s life.

A Jesuit Among Benedictines

De la Taille (1872-1933), who came from a French noble family of 11 boys, knew at a young age that he wished to become a Jesuit. Due to secularist laws which exiled religious orders from France, much of his early Jesuit formation took place on British soil, primarily at St. Mary’s in Canterbury. Weak health precluded his aspirations for missionary work, but several seasons of forced convalescence at the English Benedictine monastery of Ramsgate propagated de la Taille’s deep appreciation of the liturgy and his joy in celebrating the solemn high Mass. In fact, de la Taille developed there a life-long affection for the Benedictine order. When the anti-clerical laws were eased in France in the mid-1890s, he returned to study theology at the L’Institut catholique and earned a Licentiate in philosophy at the Sorbonne.

Theology “has no place for anything that does not foster piety.”

Not long after his ordination in 1901, de la Taille followed the counsel of a spiritual director to study the Letter to the Hebrews—an endeavor that cast a long and bright light upon his theological career. Before he began to teach at the School of Theology at Angers in 1905, he had written a Lenten series of sermons on “The Sacrifice of the Mass” and had composed retreat talks on the topic. During the decade of teaching at Angers, de la Taille immersed himself entirely in researching Eucharistic sacrifice; the depth of his study yields the unmistakable impression that he read through the entire collection of Migne’s Patrologiae cursus completes—more than 200 volumes of patristic writings.

At the end of World War I, de la Taille was invited to become a professor at the Gregorian University in Rome, where he taught until his health declined in 1930. He was a dynamic teacher, whose lectures on Thomas Aquinas drew large crowds. Though de la Taille wrote significant essays on other topics such as grace and contemplative prayer, it is his masterpiece on sacrifice that constitutes his legacy to Catholic theology.

Mysterium Fidei immediately captured the attention of theologians in Europe: it was highly acclaimed for the breadth of its scholarship and its insight; yet it likewise was fiercely criticized for its “new theory” of sacrifice. While de la Taille was quick to defend his work against the claim of novelty, it is fair to say that his study marks a distinct shift in the way that Eucharistic sacrifice had been theologically treated since the Council of Trent. He both broadens and brings into focus a richer and more traditional understanding of the Mass as a sacrifice. The methodology itself of Mysterium Fidei caused excitement within the nascent liturgical movement, as well as among those who would become important figures of ressourcement theology, which preferred scriptural and patristic texts rather than neo-Scholastic ones.

What is de la Taille’s central thesis about the Mass sacrifice and how does he demonstrate it? The answer to both of these questions will underscore the significance of de la Taille’s thought for the liturgical movement, particularly in light of its fervent desire for a fuller participation of the laity in the Eucharist of the Lord’s Day.

Theology, Piety, and the Liturgy

In the preface to his great work, Mysterium Fidei, de la Taille stipulates the purpose of theology and makes an apology for the method he follows in treating the Eucharist. A theologian, he writes, aims not to dispute, but to illuminate; not to display his own erudition or to “promote his own special findings,” but rather to augment the knowledge of faith, deepening the engagement of believers with the mysteries of Christ and the Church. Even more bluntly, he argues that theology “has no place for anything that does not foster piety.” In a word, theology is to serve the life of the Church, exciting desire for God and massaging into greater vitality the faith of the baptized.

Behind these comments lies a distaste for the systematic distillations of textbook theology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. To his way of thinking—which would be echoed by several nouvelle théologie figures—theology ought to eschew systems, even while it methodically unfolds in a necessarily organic and complexly related way. De la Taille can thus justify the length of his work, as well as his prolix quoting from the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, as inevitable to a coordinating and elucidating doctrine of the Eucharist. He also begs the reader not to simply read a part of his work—for no part in a living organism can be completely understood apart from the whole. (Given the length of the book, and the fact that only the first two volumes have been translated into English, I suspect the author’s wish is frequently unfulfilled, which may account for much misapprehension of his thought.)

De la Taille reveals no interest in reforming the liturgy, but rather only an earnest desire to renew the liturgy by displaying her treasures and encouraging a fuller participation in, and understanding of, ecclesial sacrifice.

If scripture, patristic authors, and Thomas Aquinas figure prominently in Mysterium Fidei, de la Taille throws wide the net of tradition and sets down for his readers an astonishing array of other theological resources: the testimony of the Church’s liturgies—attending to anaphora, collects, prayers over the oblations, and post-communion prayers; Eucharistic hymns; ancient and contemporary preaching; medieval and modern mystical writers; catechisms and conciliar documents; and even some findings of the newly burgeoning field of history of religions.

That de la Taille would consult and present the witness of the Church’s liturgies (both West and East) brought particular delight to Dom Lambert Beauduin, O.S.B. (1873-1960), who is often called the “father of the Liturgical Movement in Europe.” Beauduin praises de la Taille for recognizing that the liturgy itself constitutes an eminent place at the theological table.[1] He likewise hails Mysterium Fidei as a “new point of departure” for the explication of doctrine, noting that the title alone announces a fresh spirit and “program” for theology, one that values its mystagogical character.

Like Beauduin, de la Taille reveals no interest in reforming the liturgy, but rather only an earnest desire to renew the liturgy by displaying her treasures and encouraging a fuller participation in, and understanding of, ecclesial sacrifice. Beauduin’s efforts to restore Christian spirituality through the restoration of the high Mass on Sunday—which included the first printing of Latin-vernacular missals for the people—would have had de la Taille’s support. Others have acknowledged Mysterium Fidei as a catalyst and guiding factor in the blossoming of liturgical studies. De la Taille’s work certainly witnesses to—indeed, advocates for—concerns linked with the early project of liturgical renewal: the promotion of scriptural fluency, along with the retrieval of patristic sources; a careful listening to liturgical prayer texts; the desire for fuller lay participation in the offering of the sacrifice (more about this below); and a more frequent reception of communion. Apropos of the latter, perhaps it is not surprising that de la Taille dedicates his masterwork to Pope Pius X, the outstanding papal promoter of the liturgy.

Sacrifice As Gift

Beyond the method and concerns of Mysterium Fidei, de la Taille’s study marks a major turning point in a theology of Eucharistic sacrifice. Beauduin, for example, claims that Mysterium Fidei provides a “release” (soulagement) and “deliverance” (déliverance)[2] from the web of immolationist theories propounded since the Council of Trent, theories that located the “true and proper” sacrificial aspect of the Eucharist in the destruction of the victim. This deliverance emerges in de la Taille’s studied depiction of sacrifice in the Old Testament, highlighting that sacrifice involves two central acts: immolation and oblation, with oblation positioned as the determining component of sacrifice. Without the giving/offering of a gift to God, there is no sacrifice. Immolation, strictly speaking, is the destruction of the victim, either one already offered to God by the presiding liturgus (the priest), or one to be offered. The priest alone can transfer the gift into the possession of the deity; whereas, the slaying of the victim can be carried out by another. Oblation, then, is the soul, the form of the sacrifice; immolation constitutes its essential material element.

At the Last Supper, Christ makes manifest his interior desire to offer his death to the Father.

When considering the sacrifice of Christ, de la Taille argues from early sources that the Last Supper and the Cross are conceived as a single sacrifice, with the oblation occurring at the Last Supper, and the immolation on the Cross. This vision places the spotlight on the Supper, where Christ, acting as priest and victim, willingly offers himself to the Father, thereby deputing himself to the immolation that would follow. Christ offers himself by way of bread and wine, which he declares to be his body and his blood poured out for many. Here is the new covenant in blood. Here the victim-to-be-immolated is present and is offered. The sacrifice has begun, which will be consummated by the immolation on the cross.

What this means for the Mass-sacrifice is clear and astonishing. At the Mass, as at the Last Supper, there is a real offering of Christ’s passion and death because the Body and Blood are present (via the consecration). The oblation at the Mass, as at the Supper, is real and present (realis et praesens); the immolation is mystical, or in sacramento. The Mass is a true and proper sacrifice because of the identity of the victim offered—a victim now already-immolated some 2,000 years ago on Golgotha. The Church can offer this same sacrifice because of a derivative power granted by Christ to his Spouse, the Church. Christ associates as his own the ecclesial offering of his Body and Blood, thereby securing the unity between the Supper-Cross sacrifice and that of the holy Mass.

In other words, de la Taille directs our attention not to looking in the Mass for an immolation or crucifixion in order to shore-up its sacrificial reality, but rather to looking for the Crucified One—and the offering of that Victim. Underscoring the oblatory element of sacrifice is concomitant with de la Taille’s treatment of the role of the baptized at the ecclesial sacrifice.

Fruits of the Mass

At the Last Supper, Christ makes manifest his interior desire to offer his death to the Father. In the Eucharistic liturgy, the Church gives expression to her own desire to offer sacrifice to God by offering the eternally and infinitely acceptable Gift: the Body and Blood of the Son.

In fact, offering sacrifice (latria) requires the accompaniment of an interior devotion and a willing surrender of oneself to God. The external offering of a gift to God is the sign of the worshiper’s devotion. Because both soul and body share in the fallen condition, an external indication of latria is necessary. The love and submission of the interior will are both signified and actualized in the gift being handed over to God. De la Taille alludes to sacramental language here: the giving over of the gift is the res et sacramentum of sacrifice; the res tantum, the reality itself, is found in the interior offering.

The fruits of the sacrifice can be limited when the interior, subjective aspect of sacrifice is missing.

This robust connection between the interior will and the external gift-giving aspect of sacrifice draws attention to the subjective element in sacrificial action, accentuating a vision of the offering Church. Rather boldly, de la Taille suggests that the fruits of the sacrifice can be limited when the interior, subjective aspect of sacrifice is missing. This point needs careful delineation.

On the basis of what is offered, every Mass-sacrifice is equally, infinitely, and abundantly efficacious—for the Victim offered is eternally accepted and acceptable to the Father. However, the fruits of a particular Mass-sacrifice are “restricted” by the offerers, that is, by the measure of their affect in offering the Gift. The participation of the faithful in the offering of the sacrifice clearly matters. While the promised presence of the Holy Spirit—the very Amor of the triune God—assures that every Mass bears sacrificial fruit, de la Taille awakens the faithful to the significance of doing what Jesus did at the Last Supper, namely, putting on display his interior will to surrender himself to the Father in sacrifice.

Baptism disposes the believer to do the same in the offering of ecclesial sacrifice. How intimately involved are the faithful in the offering of the Victim? How much is that Gift an authentic sign of our desire to offer ourselves latreutically (in worship and praise) to God? Is there a promise of surrender at the altar? Does the heart, with all its capricious desires and fervent petitions, find a place on the altar of sacrifice? If not, such an unconsidered and incomplete oblation can limit the abundant fruits that flow from the generous font opened up by the Gift of Christ’s Body and Blood.

Baptism and Ecclesial Sacrifice

In Book III of Mysterium Fidei, de la Taille reveals the crucial role of baptism for ecclesial sacrifice and for a liturgically oriented spirituality. Baptism is a mystical death through which the new Christian is immolated with Christ and commits himself to a lifelong process of spiritual mortification. This spiritual commitment is intimately related to the liturgical offering of sacrifice at the Mass. Let me spell this out.

At baptism, the believer receives Christ’s priestly character. With St. Thomas Aquinas, de la Taille affirms that the water and the verbal formula together bestow Christ’s priestly character, which immediately introduces and “indicates in us an interior immolation to God (in terms of an immolation of the life of sin, of the flesh, and of the death-dealing world, in order that we might live unto Christ through grace)” (IV Sent. D. 26, q.2, a.3, ad.2). Baptism thus inaugurates Christic life, impressing the priestly character that allows the believer, in grace, to offer his own interior immolation with the ecclesial offering of Christ’s death.

Baptismal character allows the ecclesial sacrifice of Christ’s body to be a true sign of the believer’s interior immolation, borne out in the whole of spiritual life: in prayer and ascetical practice, in repentance and self-denial, and in the handing over of those parts of life which we yet wish to have under our own control. All of this is a prolongation of baptismal death oriented to the Eucharistic sacrifice; all is the ongoing unfolding of the grace of Christ’s priestly character.

Every offering of ecclesial sacrifice provides a practical opportunity for believers to claim and perpetuate their profession of baptism.

To participate in the Church’s ritual oblation indicates an “Amen” to disposing oneself for death, for the “crucifying” of those desires which yet resist the divine will. Emphatically, de la Taille calls for an ecclesial oblation aware of its baptismal promise to imitate the sacrificial death of Christ. The disciplining of desire presses upon daily spiritual life only with unequal force (e.g., with much more intentionality during Lent). Still, de la Taille wants us to see this obligation as fundamentally one with the offering of ecclesial sacrifice.

Each time the believer participates in the sacrifice of the Mass, however generously or sparingly he offers, that oblation is being mingled with the one death which redeems all (minimal) efforts and failures of love. And this is certainly good news, as none of us is always as keenly aware as we might be of our participation in the offering of the Mass-sacrifice. The Church raises up that Gift which converts impure desire into the holy image of the Son’s single-hearted and divine desire for the Father.

Baptismal Breakthrough

This is a rather remarkable baptismal theology for the early decades of the 20th century, and one which gave momentum to those prophets of the liturgical movement. To be sure, new life was breathed into the sacrament of baptism at Vatican II, particularly in Lumen Gentium (see nn. 34, 40). Yet even here, the Council Fathers do not provide a robust theological account of the manifest connection between baptism and the ecclesial sacrifice. De la Taille’s work helps to fill this lacuna.

One hears frequently enough that Confirmation is that sacrament by which a young man or woman can finally make “their own” a sacrament which happened to them as in infant. De la Taille would find this a misleading sentiment. In fact, every offering of ecclesial sacrifice provides a practical opportunity for believers to claim and perpetuate their profession of baptism.

For the liturgical renewal still underway in the Church, de la Taille recalls how baptism empowers and obligates the Christian to offer sacrifice—and with a movement of heart and will that lends authenticity, sincerity, and vitality to the Mass oblation. From an opposite angle, it is also true that Eucharistic sacrifice bestows value and dignity on all the spiritual-ascetic efforts of the Christian disciple. When prayer, fasting, charitable acts, the denying of desires, etc. are placed on the altar and mingled with the chalice of Christ’s blood, de la Taille envisions that they are thereby changed like the water of Cana into the wine of salvation.

Michon M. Matthiesen, S.T.L, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Theology at The University of Mary (Bismarck, ND). Her book on Maurice de la Taille (Sacrifice as Gift) was published by CUA Press in 2013. She is currently working on topics in Monastic Studies and Literature and Theology.

Notes:

“Le Saint Sacrifice de la Messe: A propos d’un livre recent,” Les questions liturgiques et paroissiales VI (1921), 197-198. For a fine biography of Beauduin, see Sonya Quitslund, Beauduin: A Prophet Vindicated (New York: Newman Press, 1973). ↑

Ibid., 202. ↑

Sorbonne Image Source: AB/Wikipedia