In his recent article, “‘Idle’ Worship: Religious Structures and the Redemption of Time during Pandemic” (May 2021 Adoremus Bulletin), Benedictine Abbot Austin G. Murphy admirably underscores the importance of using free time well for one’s spiritual growth, and how it requires implementing structures in the form of beneficial liturgical and devotional practices. COVID-19 has affected daily habits and routines, and we should indeed reflect upon the structures we have implemented or failed to implement for use of our time, and particularly for those of us who are among the laity. Forced changes to our daily lives can be tremendous opportunities for growth, and so we should take the words of Winston Churchill to heart: “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” I wish to pick up the conceptual thread of Abbot Murphy’s insightful piece by focusing on the importance of one liturgical practice for purposes of sanctifying time: the Divine Office.

Merton and Joe

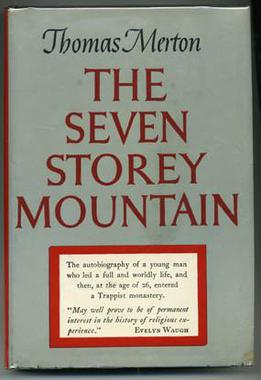

It took until my junior year in high school before I had heard of the Divine Office. One evening while my father and I drove around taking landscape photographs, he asked whether I had ever read Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. I had not. But the next day, I was in Barnes & Noble (before bookstores became mostly extinct) searching for a book on photography. While walking through an aisle, my eye happened upon a book with an arresting picture of a mountain on the cover: The Seven Storey Mountain. With my father’s comment still fresh in my mind, I purchased it and proceeded to my favorite coffee shop (Mo Java) where I devoured Merton’s autobiography.

Merton spoke in a particular section about how he began the practice of praying the Divine Office (and much to my consternation at the time, frequently quoted Latin phrases from the Psalms, before I had learned Latin). His description of praying the Psalms of the Divine Office while gazing out the window on a train to and from retreats at the monastery intrigued me. He riffed on the beauty of weaving the Psalms into the fabric of his day, during the breaking of the morning sun and the night darkness enveloping the countryside, and prayer in general. The copious amounts of caffeine I consumed that day in the coffee shop (I indeed had mo’ and mo’ java!) had conspired with grace and Merton’s words to bring about a singular change in me.

Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain speaks in a particular section about how he began the practice of praying the Divine Office. “His description of praying the Psalms of the Divine Office while gazing out the window on a train to and from retreats at the monastery intrigued me,” writes Anthony Alt. “He riffed on the beauty of weaving the Psalms into the fabric of his day, during the breaking of the morning sun and the night darkness enveloping the countryside, and prayer in general.”

As a result of this java-fueled “Merton moment,” as I call it, I tracked down a copy of the Divine Office so that I could punctuate my own days with it. Over the course of the past 25 years (and after having learned Latin), I have come to know firsthand the essential structure that the Divine Office provides to time and the spiritual life, particularly for a layman.

Present Each Day

Each day is new; each day requires that its time be sanctified. But one must know the why before the how, and that starts with appreciating the concept of time. “In Christianity time has a fundamental importance. Within the dimension of time the world was created; within it the history of salvation unfolds, finding its culmination in the ‘fullness of time’ of the Incarnation, and its goal in the glorious return of the Son of God at the end of time. In Jesus Christ, the Word made flesh, time becomes a dimension of God, who is himself eternal” (Pope St. John Paul II, Tertio Millennio Adveniente (TMA), 10). Moreover, “[f]rom this relationship of God with time there arises the duty to sanctify time.”

Because “Christ is the Lord of time [and] its beginning and end,” that means that “every year, every day and every moment are embraced by his Incarnation and Resurrection” (TMA, 10). Therefore, Christ is the focal point of time, and time should be viewed in relation to him. This implies an intrinsic connection between our calendar year and the liturgical year, and our days should be “permeated by the liturgical year” (TMA, 10).

As part of the Church Militant, our “most pressing duty” is “to live the liturgical life, and increase and cherish its supernatural spirit” (Pius XII, Mediator Dei (MD), 138). Thus, our duty to sanctify time is inseparable from living a liturgical life.

Let the souls of Christians be like altars on each one of which a different phase of the sacrifice, offered by the High priest, comes to life again.

–Pope Pius XII

Our efforts to sanctify time by living a liturgical life, however, are not aimed at an abstract, impersonal goal. Rather, they are aimed at closer union with Christ himself, and that union is tailored to each person. The Church’s “sacred liturgy calls to mind the mysteries of Jesus Christ” and “strives to make all believers take their part in them so that the divine Head of the mystical Body may live in all the members with the fullness of His holiness. Let the souls of Christians be like altars on each one of which a different phase of the sacrifice, offered by the High priest, comes to life again, as it were: pains and tears which wipe away and expiate sin; supplication to God which pierces heaven; dedication and even immolation of oneself made promptly, generously and earnestly; and, finally, that intimate union by which we commit ourselves and all we have to God, in whom we find our rest. The perfection of religion is to imitate whom you adore’” (MD, 152).

Call the Office

But how is all of this done? In a particular way, this is accomplished through the Divine Office. The Divine Office provides both the pillars for the edifice of each day and the windows streaming in light to permeate the different periods of each day. The liturgical life, of course, has as its end the worship of God, “which is based especially on the eucharistic sacrifice,” but it “is directed and arranged in such a way that it embraces by means of the divine office, the hours of the day, the weeks and the whole cycle of the year, and reaches all the aspects and phases of human life” (MD, 138). Each day is a building block, and when these days are stacked together, buttressed by the Divine Office, one’s life gradually and consistently is sanctified through the praise of God and becomes a “sacrifice of praise,” which each of us is called to do (Hebrews 13:15). Indeed, the Divine Office “is devised so that the whole course of the day and night is made holy by the praises of God” (Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC), 84). For good reason then the Divine Office is referred to as the prayer of the “Mystical Body of Jesus Christ” (MD, 142). The Divine Office centers “especially around the person of Jesus Christ” (MD, 151), and by praying it at different points throughout the day, time becomes infused with the praise of God, and Christ is invited into our unique circumstances.

Structure, yes, we need structure to our day, our life. No other opportunity for such structure surpasses the Divine Office in sanctifying our time. It continually keeps us united with Christ. But I write especially for those readers who perhaps have not yet recognized the efficacy of the beautiful and ancient tradition of praying the Divine Office and perhaps have not made it an integral part of their lives.

The Divine Office “is devised so that the whole course of the day and night is made holy by the praises of God”

The Divine Office is not restricted to priests and religious; the Church encourages the laity to pray it as well (SC, 100). The laity, in particular, need this holy structure to their days, which have twists and turns unforeseen, often wearying. But therein lies the beauty of the Divine Office. The circumstances of life are connected back to Christ, and we are able to embrace every moment as a manifestation of the will of God. And our lives, through that embrace, render praise back to God. The Divine Office is also referred to more recently as the Liturgy of the Hours, a title which perhaps more clearly brings out a particular aspect of what is occurring through our praying of it: the hours of the day, the hours of our lives, are given back to Christ, and he is praised. Our entire days and hours are rendered, as it were, a liturgy.

Make a Plan

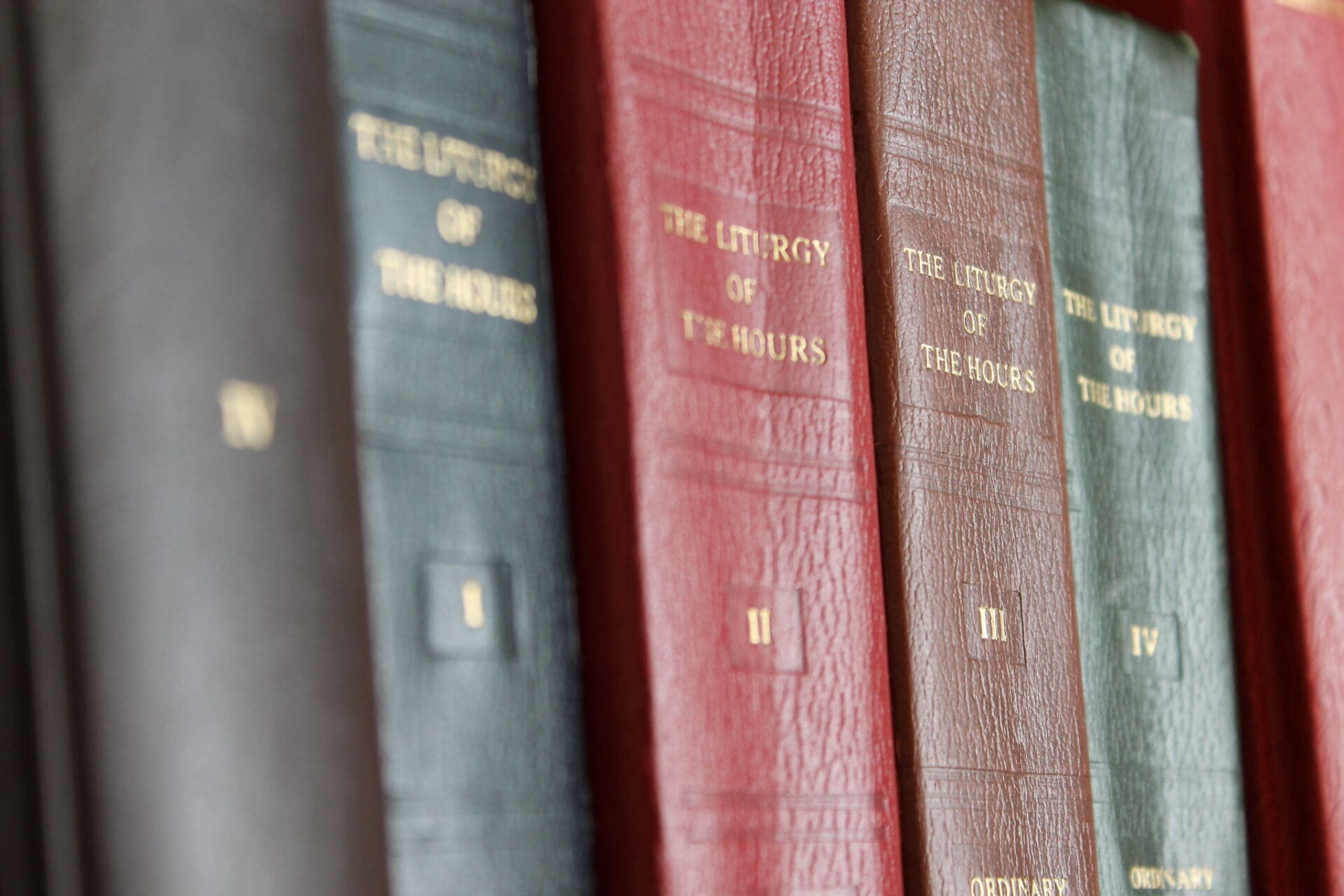

So for those of you open to something new for your days, perhaps this can be your “Merton moment”—as it was for me so many years ago. Consider taking up the Divine Office. If you are unfamiliar with Latin and praying the Divine Office in general, you can ease into making it part of the rhythm of your day in several ways. First, I would encourage the practice of praying with an actual book (not a phone or computer monitor), with pages before you that you can feel and flip. Holding the words in your hands accords with human nature’s innate desire to possess something tangible; it allows you to see, touch, and say the words. For beginners, the one volume Christian Prayer in English will provide you with everything you need to get started. Christian Prayer follows the liturgical calendar of the Ordinary Form, is relatively inexpensive (and used copies are even more so), and it is also portable. Besides price, the key difference between the one-volume Christian Prayer and the four-volume Liturgy of the Hours is that Christian Prayer does not have the Office of Readings (comprised of three Psalms and two substantive readings) for each day. The daily format of the Divine Office has the following “Hours” for prayer:

- Office of Readings (also called Matins) can be prayed at any time during the day or night.

- Morning Prayer (also called Lauds).

- Daytime Prayer requires only one of the following in the Ordinary Form (though you can pray all three):

- Mid-morning Prayer (also called Terce).

- Midday Prayer (also called Sext).

- Mid-afternoon Prayer (also called None).

- Evening Prayer (also called Vespers).

- Night Prayer (also called Compline).

Because each of these sets of prayers only takes a few minutes, carving out the time will not be overwhelming. The ideal is to pray each “Hour” during the approximate time period that it occurs during the day. Thus, one should strive to pray Morning Prayer before or around breakfast in the morning before the day is underway; Daytime Prayer occurring at some point between Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer; Evening Prayer around dinner time; and Night Prayer prior to going to sleep to complete the day. Daytime Prayer and Night Prayer are the shortest of the Hours, though in some ways the most important. It is essential to turn the mind and heart to God during the course of the day, and again before we sleep. Besides being a beautiful way to adorn one’s day, these prayers are also brief, which makes it easy to remain steadfast in praying them.

Because “Christ is the Lord of time [and] its beginning and end,” that means that “every year, every day and every moment are embraced by his Incarnation and Resurrection” (TMA, 10). Therefore, Christ is the focal point of time, and time should be viewed in relation to him. This implies an intrinsic connection between our calendar year and the liturgical year, and our days should be “permeated by the liturgical year” (TMA, 10).

If you follow the liturgical calendar of the Extraordinary Form, look for a Roman Rite diurnal, which contains all of the Hours except Matins. Unless you are familiar with Latin, however, it would be advisable to consider using an English translation in order to first accustom yourself to praying the Divine Office. The Divine Office in the Extraordinary Form is longer than the revised Liturgy of the Hours in the Ordinary Form.

Beginners should not try tackling the Divine Office in the Extraordinary Form all at once. Try one or two of the Hours. It is better to pray less, but to do it devoutly, than to hurriedly pray more. For the laity in particular, there is no canonical obligation to pray the Divine Office; this fact should help discourage rushing through the Psalms and readings from Sacred Scripture merely for the sake of completing every part of the Divine Office. Besides, such haste is counterproductive: the Divine Office should be about praising God, not showing God what you can do.

In addition, when you first obtain a breviary (whether Christian Prayer, the four-volume Liturgy of the Hours, a diurnal, or the Roman Breviary), take the time to read through the rubrics which give the instructions and describe the different sections of the book.

If, however, you cannot resist the latest technology or prefer not to purchase a physical book, there are numerous apps online that you can use that will provide you with the relevant Psalms, antiphons, readings, and prayers for each Hour. The convenience of accessing everything on your phone requires praying with your phone, which requires making some adjustments mentally. A phone is used for many things, precluding it from being entirely dedicated to worshiping God in the same manner as a breviary. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on using the phone to directly praise God and refrain from any other use during prayer time. You have to silence your phone and your mind. And there should be some period of time before and after praying during which the phone is not being used for checking the Internet or reading and responding to messages. That way, your time of prayer is carved out, not blurred with the mundane.

The Family Hour(s)

For those with a family, the Divine Office is an excellent way to pray together. From experience, our family has found that children are keen on having a copy of the Divine Office they can call their own once they can start reading (particularly if it has a zipper cover). Keep it somewhere accessible. I will often pull out my breviary while sitting at the table or while on the couch and invite whomever is closeby to pray with me, though keeping it always as an option, not as something mandatory. Even if there are no takers, if I say the words quietly, those within earshot will often chime in to the parts they know, even if while doing something else.

When it comes to praying the Divine Office, there really is no time like the present.

Such invitations at times like Saturday morning coffee or at night when the evening winds down are low-hanging fruit, ripe for the picking. But do not wait for the perfect time to pray, whether by yourself or with those in your family, because the “perfect” time is elusive and chasing it is a quixotic endeavor. I make a special mention about endeavoring to pray at least one of the Hours together with your spouse, particularly Night Prayer, which firmly strengthens the bond between spouses. Night Prayer in particular is an opportune time to acknowledge our sins and shortcomings of the day and seek forgiveness not only from Our Lord, but our beloved spouse. It is a balm at the end of the day.

The Divine Office is also well-suited for other gatherings. Men in particular need something to do in common, and so before enjoying a beer together (for example), men could try praying the Divine Office in an informal setting, giving them a common purpose. In this way, men will find in the Divine Office an uplifting prelude to praising the goodness of God’s creation through more fermented means.

How Soon Is Now?

For those already praying the Divine Office and perhaps for whom this form of the liturgy has become rote, let your spirit be quickened by the beauty and dignity of what you are doing. Double down. Those praying the Divine Office are “sharing in the greatest honor of Christ’s spouse, for by offering these praises to God they are standing before God’s throne in the name of the Church their Mother” (SC, 84). In addition, look for ways to teach others to pray the Divine Office.

And for those priests charged with leading a parish, take to heart the exhortation that “[p]astors of souls should see to it that the chief hours, especially Vespers, are celebrated in common in church on Sundays and the more solemn feasts” (SC, 100).

When it comes to praying the Divine Office, there really is no time like the present. Nunc coepi (“Now, I begin.” Psalm 77:10).