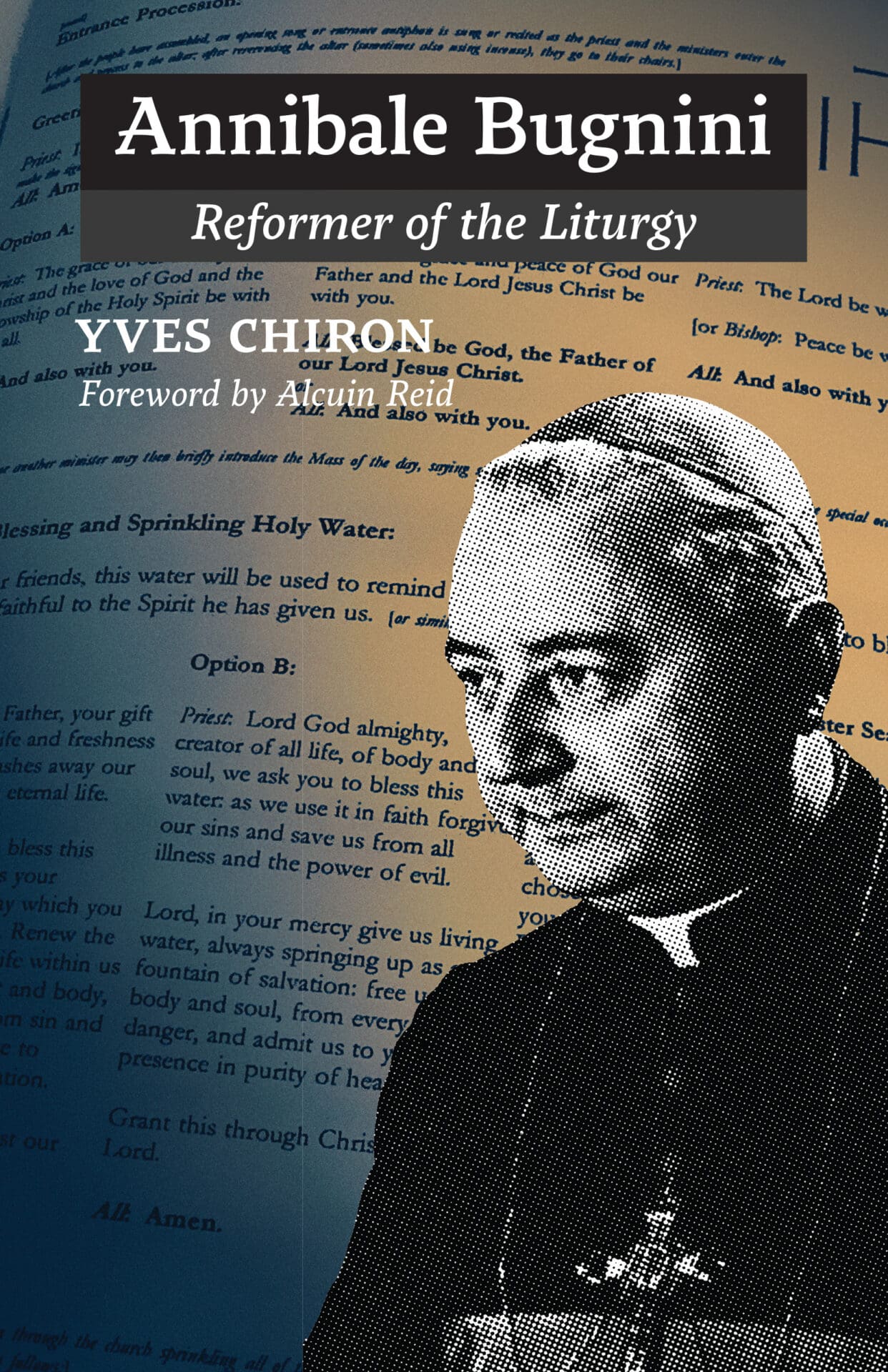

Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy by Yves Chiron, Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2018. 200 pp. ISBN: 978-1621384113. $17.95 (paperback).

Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy by Yves Chiron, Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2018. 200 pp. ISBN: 978-1621384113. $17.95 (paperback).

Richard John Neuhaus once said, reflecting on his experience of a liturgical week held in Washington, D.C., after the Second Vatican Council, that he imagined the voices of the pre-conciliar Liturgical Movement lamenting, “That is not what we meant. That is not what we meant at all.”[1] While implying a negative judgement regarding the post-conciliar liturgical reforms, Neuhaus’ remark denotes certain truths that any informed observer could agree upon. First, in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, stark changes were introduced into the liturgy. Second, many of these changes went beyond what was explicitly called for by the text of the Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium. Even those most amenable to the liturgical reforms could rightly ask, how did we get here?

Obviously the liturgy does not arise nor develop in a vacuum. A clearer understanding of the post-conciliar liturgy requires us to view it through the lens of history, focusing on the ideas, movements, and people that most influenced the liturgical reform. Few people exerted as much influence over the liturgy in the 20th century as Annibale Bugnini. In fact, controversy surrounding the liturgical reforms is often focused on the person of Bugnini, almost as if he were the reforms personified. Hence, any inquiry into the shaping of the post-conciliar liturgy will lead ineluctably to one of its primary architects, Archbishop Bugnini.

Historian Yves Chiron has filled a lacuna with his biography of Bugnini, Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy, which details the prelate’s role in the reform of the liturgy. While Bugnini wrote an account of the reforms[2] as well as his own memoirs,[3] Chiron has produced the first monograph committed to this churchman. Bound inexorably as Bugnini was with the liturgy, any biography of Bugnini will also be equally an historical record of the reforms of the liturgy. Chiron’s pursuit in this book is to give an account of Bugnini’s role in the post-conciliar liturgical reforms, specifically asking, “To what extent did Archbishop Bugnini respect the Council’s wishes? How, and why, did he go well beyond them?” (12). Bugnini himself wished to be remembered as a servant of the Church who loved and cultivated the liturgy.[4] The picture that emerges in Chrion’s book is of a skilled organizer, deeply shaped by his personal experience of the liturgy, and a figure who exerted significant influence on key members of the hierarchy. Nevertheless, despite the wealth of detail provided by Chiron, the figure of Annibale Bugnini still remains somewhat enigmatic.

French author Yves Chiron, though perhaps not as well known in the English-speaking world, is a prolific Church historian. His treatment of Annibale Bugnini is situated within a constellation of his other related works on topics such as the history of ecumenical councils, and biographies of Popes John XXIII and Paul VI. Chiron’s work on Pope Paul VI is particularly relevant for his biography of Bugnini, as these two churchmen collaborated closely on the post-conciliar liturgical reforms. Chiron’s books on Pope Pius IX and Pius X have also been translated into English.

Biography of Reform

Annibale Bugnini: Reformer of the Liturgy is simultaneously a biography of Archbishop Bugnini and a history of the reforms of the liturgy. As the latter, Chiron’s book functions well as a brief introduction to the origins and unfolding of the changes brought about by the Second Vatican Council, with helpful references to the work of the Liturgical Movement and the Pian Commission prior to the Council, also providing detailed accounts of the conciliar preparatory commission as well as the Consilium tasked with implementing the Council’s Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. Readers unfamiliar with the unfolding of the Council’s reforms will benefit from this succinct history of the key events, persons, and documents. Readers should be aware, however, that at times the work is so focused on describing the liturgical reforms themselves, that it digresses at length from the eponymous subject of the book.

Presented chronologically, many readers will be particularly interested in the first chapter on Bugnini’s formation and early works. While those having even a passing familiarity with Bugnini may be acquainted with his work during and after the Council, the years preceding the Commissio Piana (a commission established by Pope Pius XII in 1946 to study the reform of the liturgical books) hold out a kind of promise: perhaps we could gain deeper insight into this liturgical draftsman by understanding his intellectual pedigree. Chiron does offer some general details of Bugnini’s education, and mentions likely influences. On this point, however, the reader is left wanting more details to be drawn out. Names such as Dom Cunibert Mohlberg and Dom Ildefonso Schuster are identified as authors read by the young Bugnini, but few details are given as to how these first teachers of the liturgy shaped him. The reader also encounters Bugnini’s early experience of experimenting with his own form of dialog Mass in the early 1940s, an experience which impressed upon him the imperative of promoting the participation of all the faithful in the Mass and the pastoral problems surrounding the liturgy.

As the book progresses, it underscores Bugnini’s seeming ubiquity in the world of liturgical reform. It highlights Bugnini’s service in such key positions as secretary of Pius XII’s Pontifical Commission for the Reform of the Liturgy, secretary of the conciliar preparatory commission for the liturgy, peritus during the Council (though not a member of the conciliar commission on the liturgy), secretary of the Consilium, director of the journal Ephemerides Liturgicae, and professor of liturgy at both the Pontifical University Urbaniana and the Lateran Pontifical University. Chiron demonstrates that, in the story of 20th-century liturgy, Bugnini is a primary recurring character.

Mass Weight

Beyond a mere list of Bugnini’s appointments, the author delves into many of the whys and wherefores of his weighty influence. Bugnini is often named as the person responsible for having individuals nominated to committees, organizing and coordinating the work of the groups, establishing agendas, and often promoting his own personal ideas. Bugnini’s approach was not overt though; Chiron refers to what he calls “the Bugnini method.”

“On the one hand,” Chiron writes, “it consists in having groups of experts work separately on restricted subjects and having the members vote during very few plenary meetings…. On the other hand, it also consists in refraining at the outset from excessively bold proposals that might be rejected at the Council and putting certain questions and reforms off until later, after the Council. Remittatur quaestio post Concilium (‘Let the question be postponed until after the Council’) is a recurring note during the discussions of the preconciliar commission” (82).

Indeed, it is Bugnini’s method for achieving his goals that gives his story a ring of intrigue. An influence composed of direct written or spoken interventions with a theological or pastoral content could rightly be weighed by its merits in light of history and theology. Instead, one gets the sense of a surreptitious, almost cloak-and-dagger affair. For instance, Chiron notes that during the conciliar preparatory commission, Bugnini convinced the relator of a subcommission dealing with Latin in the liturgy to withdraw his report in the face of worrisome opposition, so that it would not be presented and discussed at the plenary session of the commission. “He [Bugnini],” the author writes, “gave assurances that it would be better to give scattered indications throughout than to devote a whole chapter to the subject” (71). Chiron generously calls this Bugnini acting “with prudence.” Bugnini himself spoke of this method, proceeding so that nothing he advocated would be dismissed by the Council: “…we must tread carefully and discreetly…. Carefully, so that proposals may be made in an acceptable manner, or, in my opinion, formulated in such a way that much is said without seeming to say anything: let many things be said in embryo and in this way let the door remain open to legitimate and possible postconciliar deductions and applications…”(82). Again, it is difficult not to get the impression of a kind of covert operation, secretly functioning behind closed doors.

The reader is also frequently reminded of the access Bugnini had to Pope Paul VI and the influence he had upon the Pontiff, as well as the latter’s inimitable role in the implementation of the conciliar liturgical reforms. Bugnini spoke of spending many evenings with the Holy Father as the latter reviewed and annotated documents word by word. Paul VI displayed full confidence in Bugnini, and, in turn, the Pope exerted his authority in matters of liturgical reform. It was this access to Pope Paul VI that many of Bugnini’s opponents came to resent. In fact, the so-called Bugnini method seemed to play a role even in his dealing with the Pope. Bugnini seemed at times to exploit his access to the Holy Father. In one instance during the work of the Consilium, Paul VI expressed an opinion in terms of “it seems better….” Bugnini, however, presented the matter to the group as therefore settled. “The way in which Bugnini presented the pope’s opinion,” says Chiron, “was probably too blunt” (154). Others present at the time considered that Bugnini presented the Pope’s wishes “too absolutely and imperiously” (155). It could be argued that such an overstatement of the desires of the Holy Father could hinder the legitimate freedom of the Consilium.

Mystery Remains

A final point that will interest many readers involves Bugnini’s appointment as Apostolic Nuncio in Iran, and the persistent rumor that this exile was due to his being a Freemason. Without settling the matter, Chiron does argue that these accusations were not the determining cause of his dismissal, which should instead be explained by the disfavor of certain members of the curia. The author also helpfully produces a chronology of the origin and propagation of the accusations against Bugnini, so that the reader may form a judgement based on an accurate accounting of the evidence.

Yves Chiron’s book indeed fills a gap, providing a sustained examination into the reform of the liturgy by focusing on its primary architect. Students of liturgical history and anyone interested in how the post-conciliar liturgy took shape will find in this work details that add depth to the story of the liturgy we now celebrate and the process by which we received it. After reading the book, however, the man Bugnini still remains in many ways a mystery. Perhaps Annibale Bugnini has become so synonymous with the liturgical reforms that one’s opinion of the latter will inevitably shape how one interprets the former. If one sees the reform of the rites as fundamentally beneficial, then Bugnini is the protagonist of the story, a brilliant organizer at the service of the liturgy. If the reforms were ultimately a disintegration of the liturgy, then the same actions of the same man can be read as duplicitous machinations. Yves Chiron has provided his readers with much of the data available to the historian; he also leaves to his readers the task of drawing their own conclusions regarding this enigmatic churchman.

[1] Richard John Neuhaus, “What Happened to the Liturgical Movement?” Antiphon 6:2 (2001): 5.

[2] Annibale Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy (1948-1975) (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1990).

[3] Annibale Bugnini, Liturgiae Cultor et Amator, Servì la Chiesa (Rome: Edizioni Liturgiche, 2012).

[4] The epitaph on his tombstone reads “Liturgiae cultor et amator, servì la Chiesa.”