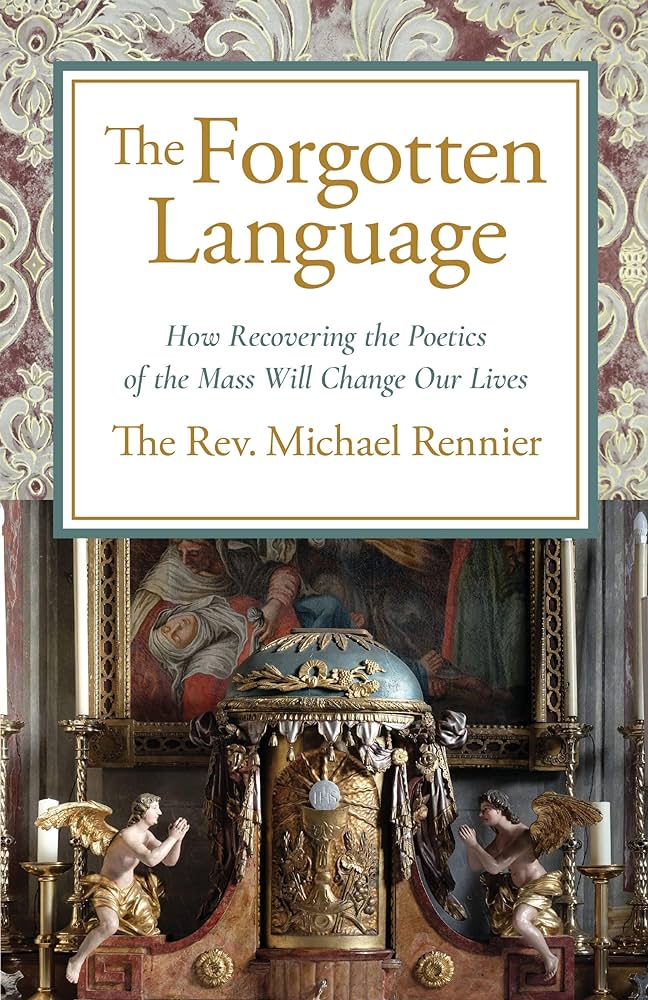

The 20th-century poet William Carlos Williams says in one of his poems, “It is difficult/to get the news from poems/yet men die miserably every day/for lack/of what is found there” (“Asphodel, That Greeny Flower”). And what is found there? That is the task, from a liturgical standpoint, that Father Michael Rennier has set himself in his new book The Forgotten Language: How Recovering the Poetics of the Mass Will Change Our Lives.

To understand what Rennier means by “recovering the poetics,” though, the reader must first understand how he undertakes the recovery mission in the first place. The book is not, strictly speaking, a scholarly work on the liturgy nor is it a work of apologetics (not in the usual sense, anyway). At times, Rennier’s book is more intuitive than discursive and operates in a mode very similar to a poem insofar as it tends to leave to suggestion what might otherwise be stated outright; at other times, it speaks directly to and through the teachings of the Church on the liturgy. Rennier balances these two approaches in his book for one purpose: to show the importance of beauty in the liturgy. But, as Rennier says on several occasions throughout his book, beauty is never easy to comprehend fully, but it is truly worth the attempt—and The Forgotten Language is no exception.

Pensive Pen

In many ways, Rennier’s book can be compared to Blaise Paschal’s Pensées, the best-known work of this 17th-century Catholic theologian and scientist—it is in this work that Paschal formulates his famous “Wager” argument for belief in God. In an essay on Paschal, the poet T.S. Eliot notes about the Pensées, “He who reads this book will observe at once its fragmentary nature; but only after some study will perceive that the fragmentariness lies in the expression more than in the thought. The ‘thoughts’ cannot be detached from each other and quoted as if each were complete in itself. Le coeur a ses raisons que la raison ne connaît point [The heart has reasons which reason does not know], how often one has heard that quoted, and quoted often to the wrong purpose! For this is by no means an exaltation of the ‘heart’ over the ‘head,’ a defense of unreason. The heart, in Paschal’s terminology, is itself truly rational if it is truly the heart. For him, in theological matters which seem to him much larger, more difficult, and more important than scientific matters, the whole personality is involved.”

Another French writer, St. Francis de Sales, helps elucidate what Eliot means by “the whole personality.” In his magnum opus, Treatise on the Love of God—a sort of sequel to his more well-known Introduction to the Devout Life—de Sales writes, “We say that the eye sees, the ear hears, the tongue speaks, the understanding reasons, the memory remembers, the will loves: but still we know well that it is the man, to speak properly, who by divers faculties and different organs works all this variety of operations.” In other words, the whole person is engaged in the operation of love, and the heart (or will) is the center of operations. For, elsewhere in the Treatise, de Sales defines love as “no other thing than the movement, effusion and advancement of the heart toward the good.”

Proceeding with both Paschal and de Sales in mind, the reader may better understand what Rennier is up to in his recovery mission. His approach engages both heart and mind, but for someone with a strong sense of the poetic, his bias tends toward the heart. The subtitle of his book (How Recovering the Poetics of the Mass Will Change Our Lives) already puts the reader on guard and on notice. The author acknowledges the instinctual distaste for poetry among the reading public when he admits, “I struggled with titling this book. I know that a book boldly proclaiming itself to be about poetics limits the number of you who pick it up to read (and thank you, intrepid friends, for picking it up to read).” But, as Rennier notes, poetics is not the same thing as poetry. “Although related to poetry and art, which are things made and incarnations of creativity, poetics is a more universal concept, one that concerns us all.” For Rennier, this concern is what the poet Williams puts so dramatically: the need for beauty in our lives is a matter of life and death—and poetics, both God’s making and our share in his making, is the means by which we come to comprehend beauty and its exacting and overwhelming purpose in our lives.

Indeed, for Rennier, poetics is as indispensable to life as breathing and eating, although it makes no claim to being nearly as practical. “Beauty seems unnecessary,” Rennier writes. “When I tell people the Mass must be a poem, they comment that it’s a nice idea, but then default to arguing for more functional purposes for the Mass. They say it must move our emotions, be relevant, cause sociopolitical change.” But such arguments see majestic oak trees as lumber and a dance of moths as a reason to buy mothballs. Rennier writes, “Poetics is the art of living. For a Christian, it’s also the art of learning to live as a saint, an exploration of what it means to claim that God is remaking us through grace.” We are the poems God is making—and he makes us, or rather, remakes us through the liturgy.

Poetic License

Already, readers may have fairly surmised that The Forgotten Language is not so much about the theological and doctrinal issues involved in the liturgy (although Rennier does include some discussion of these things); rather, Rennier seeks to help us better understand how and why the liturgy reserves for itself a language, much the way poetry does, which offers not simply delight but the graces which will lead us to the ultimate delight—a deeper union with Christ. Rennier works out this thesis through a layering of voices—a polyphony—in both his style and the texture of his thought.

For lovers of poetry, the author includes among these voices a generous variety of versifiers—Gerard Manley Hopkins, Paul Claudel, Wallace Stevens, and T.S. Eliot, and some lesser-known poets, such as Kay Ryan and Wendell Berry (in addition to the usual gang of Christian apologists, including G.K. Chesterton and C.S. Lewis). The poets Rennier cites do not specifically speak to the Catholic liturgy, but they do offer some insights into how we are to approach the liturgy—with mind and heart, intellect and will, married together in the language of the Mass. For instance, American poet laureate Kay Ryan notes, “If we are not compelled to submit in some ways to a poem it cannot change us…. We’re converts here, or we’ve quit.” To which Rennier notes, likewise, “We must fully abandon ourselves to the Mass or better not participate at all.” If such a sentiment seems excessive, you are beginning to understand the urgent premium that Rennier places on the need for beauty in our lives.

On another level, too, Rennier’s layering of voices are different aspects of the author’s own voice: the personal, the professional (i.e., priestly), the scholarly, and the artistic. The author interweaves his own experiences as a married priest—he was ordained a priest in the Anglican Church before becoming Catholic, after which he was ordained a Catholic priest under the Pastoral Provision for former Anglican clergy authorized by Pope John Paul II in 1980—with his journey to conversion, quotidian moments in his Catholic priesthood, and poignant scenes from his homelife. These experiences stand as the basic narrative for the book, but Rennier is not offering a strictly linear autobiography. The anecdotes and insights from daily life often serve as steppingstones to his reflections on the liturgy as the ultimate poem which in turn serve as epiphanies which inform and shape his personal life.

Like Paschal, Rennier works from a seemingly disconnected series of reflections; however, the reader will find, as Eliot notes about Paschal, that the disconnect is only apparent. Rennier juxtaposes lessons from life as both a priest and a father with deep dives into the theological and poetic significance of the liturgy. In doing so, he seeks to demonstrate that, as de Sales would agree, love is a matter of multi-tasking with head, heart, body, and soul.

For instance, Rennier offers a personal recollection near the beginning of the second chapter of the book, “Like a Moth to a Candle.”

“My wife Amber and I have six children who have taught me the value of paying attention the poetic shape of our lives,” he writes. “To my toddler, a generic tree is an object worthy of lingering over: a sap-scarred oak, triumphant against an ancient wind, strong as a king yet kind enough to gently drop a gift to her, a single trembling leave. She carried it home in one hand while allowing me to hold her other hand in mine.” (For those familiar with Rennier’s writing in the pages of Adoremus—and looking for more—The Forgotten Language is full of such fine passages.) In relating this moment of father and daughter beneath an oak tree, Rennier is drawing our attention to the drawn attention of his child. “Love sharpens our vision,” he writes, for those that may have missed the lesson of the oak leaf. “The lover sees most true.”

Rennier next jumps to a reflection on his celebration of the Mass as pastor of Epiphany of Our Lord Parish in St. Louis, MO. “When I celebrate Mass…and I manage to pay attention, this is what I notice….

“The wind moves slowly across the clay roof tiles. Clouds are passing. The Host almost afloat on my fingertips. The bell in the tower lazily rolls. Time is spilling out in whispered prayers…. The thurible chain bends onto itself with a sound like a waterfall. I make the Sign of the Cross, look at the crucifix, and bow over the altar to consume the Host.”

In learning to see and love as his child sees and loves the oak tree and its gifted leaf, Rennier begins to see his own trees for the forest of details in the Mass. He internalizes these lessons of the eye until they sprout with a new understanding of what draws him (like a moth?) toward the sanctuary light: “It’s an act of love to look away from ourselves. It’s a sacrifice, a spiritual death and a constant departure into the wilderness. I struggle with this calling out from myself to pay attention to God. I don’t believe God holds anything back from us—after all. He is our Daily Bread, but I fail to take and eat. The universe, my destiny, the heart of God—they’re written in a language of which I sense the meaning but cannot quite translate.”

Remember and Forget

It is this mystery to the language of the liturgy which haunts Rennier’s book; it is also, fittingly, the prime and primal focus of the book. As Rennier says, “if you find the Mass difficult, don’t give up or change it. Instead, surrender. Ask God to open your heart to His divine communication. Make yourself ready to hear.” The heart does indeed have its reasons, and only the fool saith in his heart that there is no God. As the religion writer for a secular newspaper, I’ve interviewed many members of the clergy. One Protestant minister shared with me a lesson that his father, who was also a minister, imparted to him: “‘Don’t miss heaven by eighteen inches.’ That’s the distance between the head and the heart.” For the Catholic, the “forgotten language” of the liturgy must be recovered; it is the bridge between head and heart: coordinating and reordering both in unison, heart to mind and mind to heart—and both to Christ.

“If poetry is a forgotten language,” Rennier writes near the end of his book, “perhaps that’s a feature, not a bug. A forgotten language for a people who must learn to forget themselves, who are taking on the likeness of Christ. The Mass must show us that image. How else are we to find it if not here?”

Father Michael Rennier, a gifted and insightful writer, uses his creative and scholarly talents side by side to rouse in the reader a sense of the beauty of the Mass—and he does this by rousing in the reader a sense of beauty in the words he uses to convey this beauty. The form fits the matter, as the philosophers say, and in Rennier’s case, what results, The Forgotten Language, is one priest’s remarkable and moving paean celebrating—and showing us why only the best will do when it comes to celebrating—God’s gift of the liturgy to the Church and to the world.

Joseph O’Brien is the managing editor of Adoremus. He writes a bi-monthly religion column for the San Diego Reader, “Sheep and Goats” (https://www.sandiegoreader.com/news/sheep-and-goats/).