A Centenary of Romano Guardini’s The Spirit of the Liturgy, Part III

Editor’s note: This examination of Chapter Three of Romano Guardini’s The Spirit of the Liturgy is the third in a series of seven essays marking the centenary of Guardini’s book.

Theologian David Tracy once told a lecture hall filled with Masters students a ‘parable’ about the difference between the workings of a German mind and those of an American one. He said that when his German theologian friends arrive at an airport in the United States, they place their luggage and briefcases neatly and orderly in the trunk of the automobile—be it a taxi cab or rental car. Whereas, he noted, when travelling with his American colleagues, they simply toss their valises into the trunk without a thought to symmetry, balance, or the careful fit of the space available before them.

This image returned to my mind while preparing to write on the third chapter (“The Style of the Liturgy”) of Guardini’s The Spirit of the Liturgy. Guardini’s liturgico-spiritual classic is so neatly organized and arranged that a single piece of it depends for full comprehension on contiguous parts, as well as on the whole frame. Moreover, this particular chapter on ‘style’ exemplifies the predilection of his German-trained, if Italian-born, soul for distinctive order and fruitful tension (suitcases carefully arranged in a trunk to remain fixed by their very tensive contiguity).

In chapter one, Guardini orders the proper balance in liturgical prayer between thought and emotion, and between nature and civilization. Chapter two reveals the delicate polarity between the individual and the community in the liturgy. In chapter three, while explicating the style of the liturgy, Guardini draws attention to the inherent tension in the liturgy between individual expression and the universal, between historical time and the eternal, and between the warm ebullience of private devotions and the reserved style of the Church’s public prayer.

Though writing in 1918, as the final battles of the Great War subsided, Guardini’s articulation of what constitutes the style of the liturgy remains essential and as desperately necessary for the restoration of the twenty-first century soul—distracted, enslaved to time, and appallingly “selfy”-obsessed—as it was for the shattered, disillusioned souls of the 1920s.

Does the liturgy have a particular kind of style? Has the public worship of the Church, over the course of the centuries, developed a style, a modus operandi which best suits—is most conveniens to—the praise of God and the sanctification of his people? Guardini undoubtedly believes this to be the case, and he is persuasive about the necessity and fruits of such a style.

Unpacking “Style”

To comprehend Guardini’s vision of the style of the liturgy, we first need to grapple with the word itself. Like Augustine’s famous quip about ‘time’ in Book XI of the Confessions—we all know what it is until we need to say what it is—‘style,’ too, is a slippery term to pin down. We do know that there are styles of painting (Dutch realism, impressionism) and styles of writing (the expansive and moral prose of Victorians like Charles Dickens and George Eliot, and the modern minimalistic writing of Ernest Hemingway and Cormac McCarthy). We are familiar with styles of preaching—the scholarly exposition, the narrative homily, the evangelical double-edged sword to the heart. We are even able to note political styles of leading a country: the dictator; the prudent conciliator; the populist ‘tweeter’. But what is style? What counts for style?

Fortunately, Guardini provides us with a definition—actually, two definitions.

Guardini speaks of style in a broad sense, and then he chisels the definition to a narrower meaning. Style in the first sense obtains when any “vital principle” has found its authentic, true expression.[1] This living principle can be a biological organism, a personality, an artistic production, or even the form of a community or society. Yet, to merit the designation of ‘style’, this particular expression must prove to be of wide importance. That is to say, a truly convincing style will establish something with which others may also identify and engage: it will manifest that which is almost already familiar to others, familiar in the sense that its peculiarity is magnanimously accessible.

This definition might sound terribly paradoxical, but it is at the heart of what Guardini wants to communicate about style. The more original and impressive the expression, the more capable it is of revealing its “universal essence,” of inviting the soul into its reality. Three examples—a personality, a social body, a work of art—might help to illuminate what Guardini indicates by style in this first sense.

Person, Place & Poem

The saint is a “genius” personality who has exhibited something “immeasurably original,” a highly individual style that is not without universal relevancy. Few, for instance, would dispute the originality of St. Francis: his naked dependence upon God; his compassion for the sick and the poor; his response to rebuild the Church; his love of nature and animals; and his commitment to the way of peace and reconciliation. For almost a thousand years, this particular “Franciscan” style has had a broad appeal, and it has been generative and formative of Christians and non-Christians alike.

Similarly, a form of community can claim a style that is efficacious across time and culture. St. Benedict’s Rule, written in sixth-century Italy, established a form of monastic social life dedicated to seeking God (quaerere Deum). As Benedict XVI is fond of noting, the Rule became a “spiritual leaven” that “changed the face of Europe.” [2] The Rule would become a template for religious life across the European continent, and today it still stands as a model for religious communities, as well as for family and institutional life. The particular Benedictine vision of a school of love, its patterned rhythm of ora et labora, and its insistence upon mutual humility and obedience manifests a style which is universally significant and accessible.

Dante’s literary masterpiece La Commedia also exemplifies Guardini’s first notion of style. There is no gainsaying that Dante’s poem emerges from the very particular historical setting of late medieval Florence. The lengthy and often taxing notes provided by most editors at the end of each canto, detailing historical figures and local Florentine events, remind the reader just how temporally situated is the poem. Even so, the genius of Dante’s Commedia reaches through the particular to the universal. The poet’s narrative of a pilgrim’s journey through (and to) the afterlife achieves that uniqueness and perfection of expression which makes it also an artwork of universal style. Perhaps unwittingly, the reader finds himself walking in the shoes of Dante’s pilgrim.

Each of these instances of style manifests an arc of descending into the finite and particular in order to speak universally. This is the way of our incarnational God, who entered time and history in order to save and raise up fallen creatures. Perhaps all ‘style,’ in this first sense, is at best an imitation of this divine arc.

Law & Order

Still, Guardini wishes to refine further his denotation of style—style in a narrower sense. It is this second, “specialized meaning” of style which illuminates the nature of the Church’s liturgy. Guardini invites his reader to experience this narrow meaning of style through visual imagination.

Place before your eyes an ancient Greek temple and a gothic cathedral. Both are beautiful; both invoke awe; both are perfect expressions of a particular type which bestows profound insight about an historical period and culture. Guardini leads us to see, however, that the Greek temple has more style than the gothic cathedral.

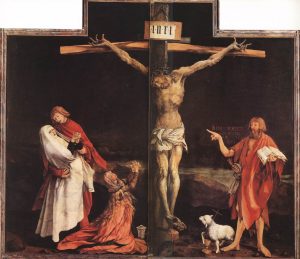

Alternatively, stand before two equally powerful paintings, one by Giotto and one by Grünewald. Even a person without the advantage of having taken an Art 101 course will see that the Giotto has more style—or so Guardini confidently affirms. This “more” is precisely what Guardini is after in considering style in sensu strictu: this style

We can see in the Paestum Temple and the Giotto painting that what is individual and of time subjects itself to what is essential and transcendent. This narrower understanding of style thus gives precedence to the universal over the historical and concrete. It manifests a simplification of the multiplicity of life, with all its particular “entanglements,” by underscoring instead inner coherence, order, and “lawfulness.”[3] Just so is the majestic style of the Church’s liturgy.

This specialized liturgical style developed organically over time. Guardini argues that the “Greco-Latin spirit” (which tends per se to this narrower sense of style), the ‘polishing’ and chiseling of liturgical symbols and gestures over the centuries, and the concentration of liturgical perspective toward the eternal, converged in such a way that a “mighty” liturgical style emerged and is now fixed.[4]

Indeed, the Council fathers at Vatican II seem to confirm Guardini’s observation when they insist that liturgical rites ought to radiate a noble simplicity (SC, 34: “Ritus nobili simplicitate fulgeant’). The Novus ordo does not eradicate this style. Far from it: the sharpening of the rites and the elimination of certain repetitions configure the liturgy more and more to the stateliness of the Greek temple and the elegant quiet of a Giotto painting.

Details, Details, Details…

This grand style is manifest in the words, gestures, colors, and music of the liturgy. Guardini has already demonstrated in chapter one of The Spirit of the Liturgy that the language of liturgical prayer leads by thought, and not by emotion. Here he points out that the stylized form of the Roman collect is emphatically more distilled and universal than the language used in private prayer to God.

Liturgical language will be more remote from a pedestrian, personal, or particularly local use of language. Whatever one may think of the revised translations in the Third Editio Typica of the Roman Missal, the language resonates with what Guardini articulates about the liturgy’s style. Liturgical dress, liturgical vessels, and even liturgical colors have also gone through a process whereby the particular and historical have been transfigured—“intensified” and “tranquilized”—in order to reach this note of universal currency.[5]

Let us consider, for instance, the Eucharistic host. It no longer directly resembles a morsel torn from a loaf of bread; rather, the bread-morsel has been simplified, intensified, flattened-out like the surface of a Giotto painting. The liturgical host is bread divested of any local peculiarity of mixing, forming, and firing ground wheat and water. And yet the host is bread, liturgically-stylized for the holy sacrifice of the Mass, a ritual which itself ruptures the division between time and eternity, between earth and heaven. The host is that meeting place between the raw wheat of the high plains and the heavenly food of angels.

In terms of liturgical music, it is not the popular hymn but rather Gregorian chant which Guardini identifies as representative of this narrow sense of style. Fifteen years before The Spirit of Liturgy, Pius X’s motu proprio Tra le sollecitudini had reasserted the use of Gregorian chant in the liturgy, claiming that it is fittingly holy (not profane), representative of true art, and universal in nature (nn.2-3).[6]

Guardini assists us further in envisioning how and why this music is most suited to the liturgy’s style. Gregorian chant simplifies the singularity and complexity of other musical modalities; it distills sound and expression, refusing to call attention to itself. Its spare atmosphere and purified sound welcomes universal participation.

Modern Baggage

If the Catholic liturgy is to be the supreme and objective rule of the spiritual life kata ton holon (for all times and cultures)—as Guardini boldly announces at the opening of his liturgical classic—a liturgy falling short of the style he depicts would fail in some measure to achieve this universality and objectivity. This is a potent mandate for attending with care to the appearance of every official public worship of the Church. Do the People of God desire this universal style sufficiently enough?

Guardini anticipated objections to this liturgical style, objections that will no doubt sound familiar to our ears a hundred years later. ‘Modern’ individuals, he writes, would prefer a style that more directly addresses their own inner life. Would not that large group of American Catholics who today forgo the liturgy because they “get nothing out of it,” because they can find nothing in the liturgy’s cold and restrictive style that “speaks” to them, confess openly this ‘modern’ predilection?

The careful arrangement of the parts of the liturgy, its generalized thought, and its formality of gesture have no immediate appeal and can often chafe against the individual’s interior disposition and emotional impulses.[7] To be sure, some congregations would prefer to fill the empty foreground of the liturgy with cultural and self-referential additions, with words and prayers and music that make the spirit (and the ego) more vibrantly throb.

How does Guardini respond to this ‘modern’ protest? On more than one occasion in the book, this perceived difficulty with the liturgy’s style is resolved by an instruction about the value and place of private prayer and devotions. The arena for interpersonal warmth and emotive religious expression is located in the wide purview of pious devotions which legitimately and necessarily supplement the Church’s official public prayer. In fact, Guardini acknowledges that the grand style of the liturgy could not be fully effective without the exercise and outlet of personal prayer and devotions.

With charm, he has called these extra-liturgical devotions “receptacles” into which believers can “pour out their hearts.”[8] So, gatherings of college youth, for example, during which “Praise and Worship” music pointedly enflames the emotions of believers, have their proper place and can be fruitful for a fuller participation in the solemn rites of the Mass or in the praying of the Liturgy of the Hours.

Creative Tension

Private prayer and devotion, measured by and oriented toward the Church’s liturgy, ought also to excite desire for the rites of the Church. For Guardini, the evident polarity between the grand climate of the liturgy and the aegis of personal prayer ought not to be construed as “mutually contradictory,” but rather as mutually cooperative.[9] The tension is a creative and spiritually healthy one.

Guardini teaches us that a heuristic guidance should be offered to those who expect that the liturgy should carry the same personal and emotional valence as private devotions.

Is the worshipper therefore mistaken who arrives at Sunday Mass expecting a warm and personal encounter with the Jesus who walked the streets of Nazareth, hugged his mother Mary, and laughed and cried with his disciples? In a word, yes.

Guardini acknowledges (and this in 1918—before the phenomena of mega-churches!) that Protestantism has “sometimes” faulted Catholic liturgy for providing only a “cold” and intellectualist concept of Jesus (Giotto’s Jesus, for instance) in its liturgy, rather than conveying the living man (the Grünewald Jesus). To be sure, the modern believer might yearn to encounter a warm intimacy with the man Jesus; yet, the Jesus who appears in the Catholic liturgy is the High-Priest who sits at the right hand of the Father, the great Mediator between man and God, the one who shall return as Judge at the end of time, and the one who is Head of his Body the Church.[10] Indeed, though the glorified God-Man descends to feed us with himself at the Eucharistic altar, he does so to make us ever more like himself, and to prepare us for eternal life around the heavenly altar.

Style Points

To my mind, Guardini’s underscoring that “something of us belongs to eternity,” and that the style of the liturgy recalls us to this truth, is perhaps the most requisite point of this chapter. Guardini wishes us to see that only a truly authentic “Catholic style” of liturgy—“actual and universally comprehensible”—is capable of orienting and summoning the human soul to that full and desired knowledge of, and union with, the Creator. The simplifying, universalizing, and “tranquilizing” (what a marvelous word!) style of the liturgy allows the soul to move about in a more “spacious” spiritual world, moving it to a recollection, as Augustine would have it, of supreme happiness, consummate joy.

The grand and noble style of the liturgy temporarily removes the shackles of time. It works a release from the prison of the self, and permits an experience of the eternal, of stillness, and of silence. The grand style of the liturgy, like the Giotto painting, promotes contemplation.

We need frankly to ask, however, whether this majestic style of liturgy proves to be what the ordinary Catholic in North America experiences? This is not widely the case, I suspect. Far too frequently, this noble style had been corrupted by a foreground of busyness; its distinct order has been muddied by the filling up of its clean spaces—with yet another song, yet another announcement, yet another prayer for vocations, etc.

The silent interstices of the liturgy have all but vanished, replaced by hurried movement and tangible distaste for decorum and ‘empty’ quietness. When the liturgy becomes more a celebration of the local community—its expressive needs—then particularity and the present crowd the liturgy’s still frame and its universal style recedes.

Liturgical Trunk Show?

Have our liturgies come to resemble that car trunk with suitcases and bags thrown in whichever way? Have we—not with malice, of course—profaned the style of the Church’s public prayer by attempting to make it more into the image of our finite, anxiety-laden, control-seeking existence?

Guardini’s deeply pastoral sensibility envisioned that the spacious and distilled atmosphere of the Church’s liturgy could restore the souls of his fellow Europeans. The style of the liturgy was, he thought, a vigorous counterpoint to the aggressive nationalistic fervor in fashion at the time of his writing. As chaplain to the youth movement Quickborn in the years after the War, Guardini placed the Catholic liturgy at the heart of this movement. In 1922, he received permission to employ the missa recitata (the ‘dialogue mass’), which allowed the people to more fully enter the grand style of the liturgy by reciting the responses of the altar servers and the ordinary of the Mass.

This visionary priest profoundly understood that the mighty style of the liturgy could reveal truth as a living reality, a reality to be contemplated by worshippers. In this second decade of the twenty-first century, Guardini challenges Catholics, clergy and laity alike, to let the grand and noble style of the liturgy have its way. Such a style ennobles the soul, inviting and permitting it to pass over into a realm of sacred openness. There, unencumbered by the self, the soul may see once more the stars, the heavens, the angels, and recall her eternal patria.

[1] Romano Guardini, The Spirit of the Liturgy, Translation by Ada Lane, Introduction Joanne Pierce, Spirit (New York: Herder and Herder, 1998) 45.

[2] See for example Benedict XVI’s General Audience address (9 April 2008) http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20080409.html

[3] Spirit of the Liturgy, 45.

[4] Spirit of the Liturgy, 46-47.

[5] Spirit of the Liturgy, 46.

[6] Pius XII’s 1947 Encyclical Mediator Dei (n. 192) and the Second Vatican Councils’ Sacrosanctum concilium (n.116) would also reiterate a preference for Gregorian chant in the liturgy.

[7] Spirit of the Liturgy, 47.

[8] Spirit of the Liturgy, 30, n.10.

[9] Spirit of the Liturgy, 50-51.

[10] Spirit of the Liturgy, 48.