Recovering the Lost Tradition of Sacred Drama, Part II

(to read part I, “St. Joseph in Old York,” click here)

In the ancient English city from which our own New York takes its name, a centuries-old tradition of Sacred Drama flourished from the late 1300s to the late 1500s. Each year for two hundred years and more, the civic authorities of the City of York worked together with religious and lay leaders to produce biblical mystery plays which were substantially shaped by Christian liturgy. By the mid 1400s the plays had coalesced into a unified cycle of more than forty-five documented pageants referred to today as The York Plays, or collectively as The York Cycle. Each play or pageant dramatizes an important event in salvation history ranging from The Fall of the Angels to Doomsday.

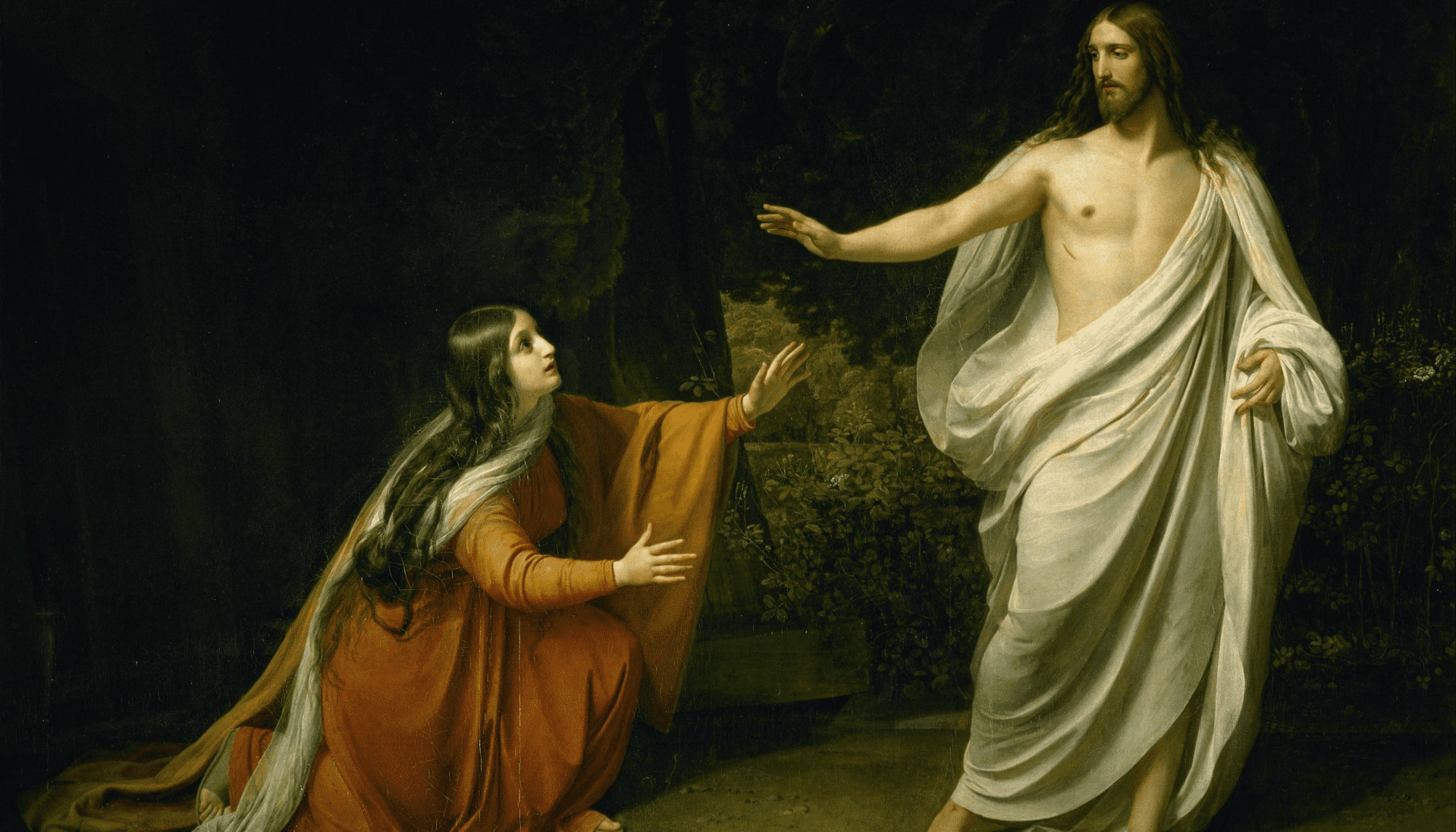

Among the most impressive plays in The York Cycle were the post-resurrection pageants, several of which place strong emphasis on Eucharistic theology. Through a variety of puns and allusions to liturgy, the play which recounts Christ’s Appearance to Mary Magdalene offers especially profound insight into the Eucharistic essence of Easter.

Sponsored by the Wine-drawers Guild, Christ’s Appearance opens with Mary Magdalene bitterly lamenting the death of her Lord (lines 1-19). Her lengthy complaint culminates in a brief prayer to the Holy Trinity: “Thou grant me grace to have a sight of my Lord, or else his sande” (lines 20-1).[1] The Magdalene’s use of the word sande, which alone is left here in the original Middle English, evokes a variety of possible meanings: it can mean command or message or messenger (and therefore angel) or even feast or banquet.[2] Opening up yet another possibility relevant to what Mary Magdalene is about to experience in her encounter with Christ, the phrase “his sande” sounds to the ear like “his hand.” All of these valences operate simultaneously on different levels of meaning in the play, as the following exposition will demonstrate.

The moment Mary Magdalene utters her prayer, Christ himself appears, unrecognized by Mary Magdalene because he is dressed as a gardener, and He says to her, “Whom seekest thou this long day? Tell me truly, as Christ commands thee” (lines 26-7). She explains that she is looking for her “lord Jesus” the “true God,” and, with the Risen Christ standing right before her very eyes, she sighs in sorrow, “I see him not” (l. 35). Seeking a glimpse of the Body of Christ with her bodily eye, Mary Magdalene reveals to the faithful the potential for their own blindness to the presence of the Risen Lord.

Rich in allusions to liturgy, the dialogue between Jesus and Mary Magdalene would have reminded medieval audiences of the introit for the Easter liturgy, which began Quem quaeritis in sepulchro? or Whom seekest thou in the tomb? At the beginning of the celebration of Easter, the clergy would typically have gathered around the altar of repose where the Eucharist had been laid at the close of the Mass of the Lord’s Supper on Holy Thursday. The return of Christ’s Eucharistic presence to its customary place above the high altar was the climactic event which immediately preceded Mass on Easter, thus bringing to a close the “long day” of the Paschal Triduum.[3]

Well did the playwrights of medieval York realize the essence of what Pope Benedict XVI has written about this great Feast of the Resurrection:

Christ’s Resurrection enables man genuinely to rejoice. All history until Christ has been a fruitless search for this joy. That is why the Christian liturgy—Eucharist—is, of its essence, the Feast of the Resurrection, Mysterium Paschae. As such it bears within it the mystery of the Cross, which is the inner presupposition of the Resurrection.[4]

Mary Magdalene’s blindness to the presence of Christ turns to sight only when she is able to discern Christ’s wounded yet resurrected Body and Blood, the miraculous Corpus et Sanguis Christi. By means of a gradual initiation into the Easter mystery, Mary Magdalene comes to recognize Jesus first of all by his wounds, and especially by the wounds in his hands. She beholds in their still-bleeding death-defiance the great power of her Lord over both sin and death. The dialogue of the play suggests that Mary may even have dared, in all her awestruck wonder, to have touched or to have kissed the wetness of his wounds, after which she exclaims, “Thy love is sweeter than the mead” (l. 89). Some lines later, Mary refers to Christ’s wounded body as “miraculous food” (l. 123).

Her initial tearful search for her Lord in the garden has been fruitful indeed. Beholding the great Paschal Mystery, Mary Magdalene understands for the first time the full essence of the Feast of the Resurrection, a feast of faith: in the mystery of the Holy Eucharist, in the sacred banquet in which Christ is received, the Magdalene comprehends at last the Mysterium Fidei: mortem tuam annuntiamus, Domine, et tuam resurrectionem confitemur, donec venias. This memorial is repeated in some form at every Mass because the Eucharistic sacrifice is a mystical sharing in the Passion and Death as the inner presupposition of Christ’s Resurrection.

[1] All quotations represent my own renderings into modern English based on the original text as collected, edited, and emended by Richard Beadle in The York Plays: A Critical Edition of the York Corpus Christi Play as recorded in British Library Additional MS 35290, Vol. I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[2] See Robert E. Lewis, Middle English Dictionary (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007).

[3] See Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580, 2nd ed., (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), p. 31.

[4] The Feast of Faith: Approaches to a Theology of the Liturgy (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1986), p. 65.