In an earlier contribution to Adoremus Bulletin, “Sacrifice as Deification: Reflections on the Augustinian Foundations of Ratzinger’s Sacrificial Theology,”[1] I had opportunity to discuss the character of sacrifice as deification. In that essay, which was a three-way dialogue with St. Augustine, Joseph Ratzinger, and Matthias Scheeben, I suggested that the key to understanding the biblical concept of sacrifice, as it was expressed in both the Old and New Testament, was to see it as the ritual burning of the victim in the altar fire on the altar of holocausts in the forecourt of the Old Testament’s tent or Temple. In the Old Testament, the altar fire represented the moment of communion with God, the telos or goal of sacrifice. In the New Testament, such burning communion is God communicating with man, whom he “inflames” with grace and the virtues. As St. Paul indicates, the most important of these virtues is charity, so we are fired by this virtue especially to lead us to our end in the beatific vision. The movement here, following the Church fathers’ reading of Hebrews 10:1, is one from shadow (the material fire of the Old Testament) to image (grace and the virtues) to reality (glory) consuming the human being and thereby rendering him a living holocaust totally devoted to God’s glory.

The thesis of this present essay builds on the argument in my last article, but it approaches its subject matter from an altogether different angle. In this essay my aim is not to inquire specifically into the nature of sacrifice, but, rather, to situate its New Testament fulfillment within a larger biblical framework, one that takes into consideration the concept of covenant and the relationship of Israel to God and thereby our own relationship with God.

Anglican Bishop and New Testament Scholar, N.T. Wright, in his Christian Origins and the Question of God series, has posited that Second Temple Judaism (i.e., at the time of Christ) conceives of Jews still as exiles awaiting return. Wright posits that one of the signs that the exile has ended is the “return of YHWH to Zion” (Isa 52:8),[2] which will take place when the glory of God comes to dwell again in the temple in Zion (as in 1 Kgs 8:10f.; 2 Chr 5:13-14; 2 Macc 2:8). Using Wright as a point of departure and in conjunction with key biblical texts, my aim in this essay is to ask about the divine fire descending from God’s glorious presence and whether there is not, accompanying the end of Israel’s exile, to be expected a new and definitive outpouring of divine fire corresponding to God’s presence in Christ. In the second half of this essay, with the help of Catholic theologian Matthias Joseph Scheeben (1835-1888), I will locate where in the New Testament the divine fire is to be found.

Exile’s End

In The New Testament and the People of God, Wright says that to understand the final things (or eschatology) as they relate to Second Temple Judaism and to Jesus, one must take stock of where Israel stands in relation to the Old Testament theology of exile: though abiding in the land, they live under the Roman yoke and have not been wholly restored to a right relation with God. Wright observes: “the need for [covenantal] restoration is seen in the common second-temple perception of its own period of history. Most Jews of this period…would have answered the question ‘where are we?’ in language which…meant: we are still in exile. They believed that, in all the senses which mattered, Israel’s [Babylonian] exile was still in progress.”[3] According to Wright, although the disaster of the Babylonian exile of the 6th century B.C. had to some extent been mitigated by the Jews’ repatriation under the Persian king Cyrus, their inability to uphold their part of their covenant with God had not been fully remedied.

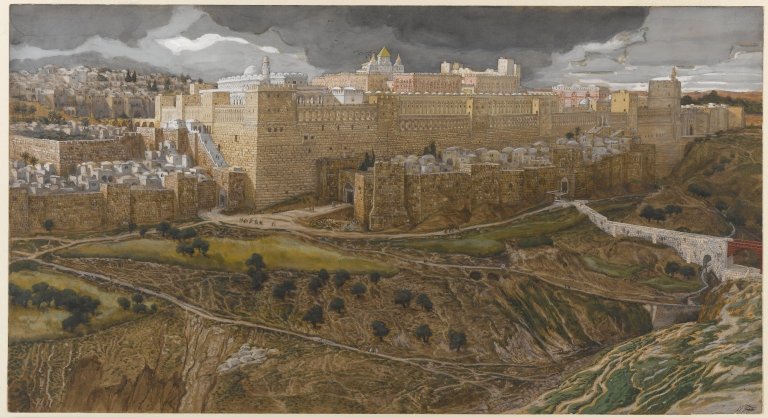

As Wright notes: “Although she [Israel] had come back from Babylon, the glorious message of the prophets remained unfulfilled. Israel still remained in thrall to foreigners; worse, Israel’s god had not returned to Zion. Nowhere in the so-called post-exilic literature is there any passage corresponding to 1 Kings 8:10 and following, according to which, when Solomon’s temple had been finished, ‘a cloud filled the house of YHWH, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of YHWH filled the house of YHWH.’ Instead, Israel clung to the promises that one day the Shekinah, the glorious presence of her god, would return at last.”[4]

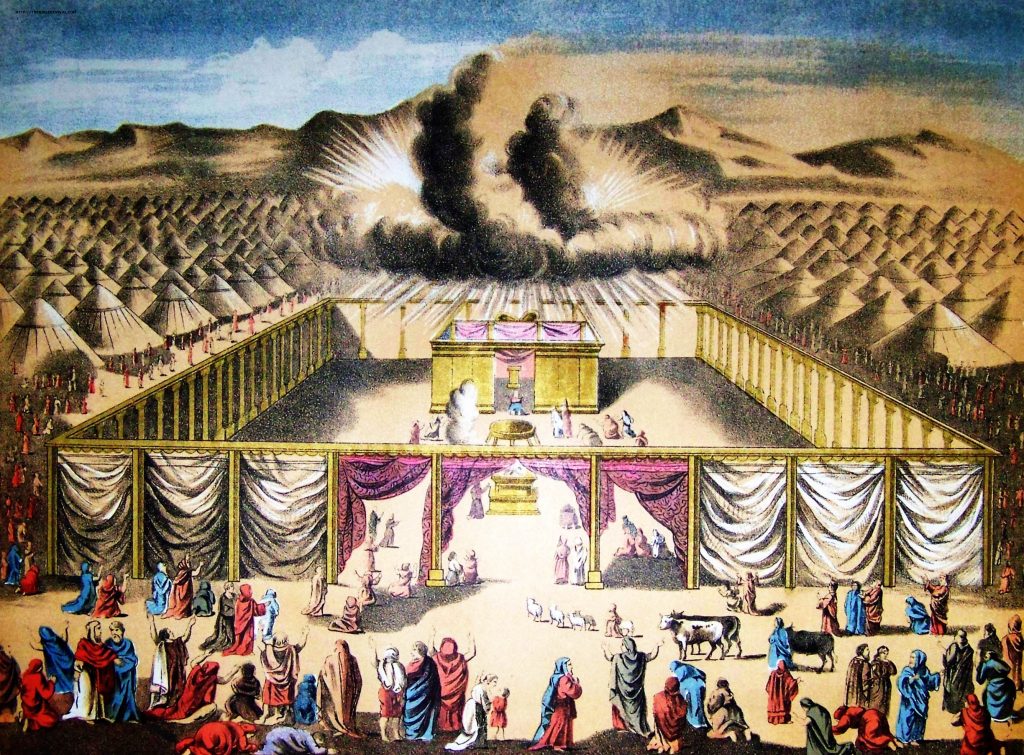

Wright’s point is well taken. There is no record of the glory connected with the pillar of cloud and fire again overshadowing the temple after the Babylonian exile, as it had first done upon the completion of the wilderness tabernacle (Ex 40:34-38); nor as it had done at the inauguration of the priestly cult (Lev 9:23-24), a phenomenon that was renewed at the dedication of Solomon’s temple (1 Kgs 8:10-11; cf. 2 Chr 7:1-2).[5] 2 Maccabees—composed in the 2nd to 1st century B. C.—even depicts the conditions of the restoration from exile jointly as A) God’s ingathering of his scattered people, and B) the reappearance of God’s glory in connection with the disclosure of the location of the lost Ark of the Covenant (cf. 2 Macc 2:5-8). Viewed in this way, since YHWH had not yet returned to the restored temple, “the exile,” as Wright puts it, “is not really over.”[6]

Building on Wright’s scholarship, I would now like to pose a question that as far as I know Wright does not address: considering the end of Israel’s exile and the anticipated fiery return of God, on the basis of the same biblical sources, could one look forward to a new descent of fire from heaven, alighting on Israel’s altar of holocausts? The basis for such an expectation is found in those biblical texts in which this fire from heaven first appears to the Israelites of the Old Testament.

The descending fire accompanies the descent of God’s glory at all the key junctures in which the latter occurs in the Old Testament texts. Thus, we first read of the descent of God’s glory on the tabernacle in Exodus 40:34 upon its completion, thereby rendering the tabernacle a “portable Sinai”[7]: “Then the cloud covered the tent of meeting, and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle.”[8] While there is no mention of a fire from YHWH in this passage—as the tabernacle form of worship was not yet operational—we do see it appear in precisely the place where we would expect to find it: with the inauguration of the Aaronic priesthood in Leviticus 9. There, we read that after “the glory of the Lord appeared before all the people…fire came forth from before the Lord and consumed the burnt offering…upon the altar” (verses 23-24).

The heavenly altar fire shows up again in the Old Testament at the dedication of Solomon’s temple. Although not mentioned in 1 Kings 8, it is mentioned in the parallel account in 2 Chronicles 5-7. There, we read that, “when Solomon had ended his prayer [of dedication], fire came down from heaven and consumed the burnt offering…and the glory of the Lord filled the temple” (2 Chr 7:1). Here again, we see the close connection between the divine glory overshadowing the tabernacle/temple structure, and the divine bestowal of the sacrificial fire.

One last text in the Old Testament is worthy of mention. 2 Maccabees 2 recounts a story of Jeremiah, at the time of the Babylonian exile, sealing up the tent, ark, and altar of incense in a cave (2 Macc 2:5). When certain persons try to disclose their location, Jeremiah rebukes them, responding: “The place shall be unknown until God gathers his people together again and shows his mercy. And then the Lord will disclose these things, and the glory of the Lord and the cloud will appear, as they were shown in the case of Moses, and as Solomon asked that the place should be specially consecrated” (2 Macc 2:7-8). While the signs of Israel’s restoration are here specified as the repatriation of the people, followed by the appearance of the glory and the cloud, the references to Moses and Solomon serve to cue up the following thematically related observation regarding the fire descending from heaven: “Just as Moses prayed to the Lord, and fire came down from heaven and devoured the sacrifices, so also Solomon prayed, and the fire came down and consumed the whole burnt offerings” (2 Macc 2:10). We see once again the close association in Scripture between the cloud, the glory, and the descending altar fire.

On a related note, 2 Maccabees 1:18-36 gives an account of the secret preservation and subsequent recovery by Nehemiah of the lost altar fire at the close of the Babylonian exile, thereby legitimatizing Second Temple worship. As Jonathan Goldstein notes, the point of the story here is to show that “the fire in the second temple was no strange fire but a continuation of the miraculous fire of the first temple.”[9] This narrative clearly shows the ritual importance attached to the miraculous altar fire in the Old Testament for the ongoing legitimacy of the sacrificial cult.

But this same narrative also raises a possible objection to the basic thrust of my thesis: if there is a record of the preservation of the altar fire after exile, is it really legitimate to expect its miraculous return as a phenomenon accompanying the so-called return of YHWH to Zion at the time of the full ingathering of Israel? In other words, if the divine fire which appeared at the beginning of the tent and tabernacle worship had disappeared with the Temple’s first destruction but then reappeared, in some way, at the return from Babylon, then why should we anticipate yet another, fuller, return? I maintain that expecting a return of the divine fire is legitimate because of the correspondence of types and figures that I’ve noted above. Note, for example, that the preservation of the fire kindled in Leviticus 9 did not rule out a fresh outpouring of it in 2 Chronicles 7. More to the point, when YHWH does in fact return to Zion for the eschatological ingathering of the people, he will do so in a quite new and unexpected way, one which surpasses the reality found in the “copy and shadow” of the Old Law (Heb 8:5)—that is, he will return in the person and work of the God-man, Jesus Christ.

So as to identify the reality in the New Testament corresponding to the Old Testament foreshadow of the descending fire, let us now turn to the writings of Matthias Scheeben and see what light they might shed on where this New Testament fire is located in connection with the person and work of Jesus Christ.

Heart-blood of the Logos

In Jesus and the Victory of God, Wright posits that Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem during Holy Week is in fact YHWH’s long-awaited return to his sanctuary. “Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem, climaxing in his actions in the Temple and the upper room,” he writes, “was intended to function like Ezekiel lying on his side or Jeremiah smashing his pot. The prophet’s action embodied the reality. Jesus went to Jerusalem in order to embody the…coming of the kingdom. He was not content to announce that YHWH was returning to Zion. He intended to enact, symbolize and personify” this return.[10]

The dynamic of YHWH’s return that Wright here examines on the level of Jesus’ public ministry—but which is built on the back of a relatively high theology of Christ[11]—Matthias Scheeben develops in terms of a metaphysics of the person and work of Christ, with Christ’s work here being seen as an emanation of his identity as the Word Incarnate, with its accompanying interior graces. Put simply, for Scheeben, Christ’s interior unction of perfect sanctity perfumes the disciples once the vessel of his body has been shattered.[12]

Christ is Emmanuel, God-with-us, God drawing-near, God come to dwell in the midst of his people Israel and, indeed, the whole human race by the very fact he is the one who has been anointed with the unction of the divinity par excellence.[13] “The anointing of Christ,” Scheeben writes, “is nothing less than the fullness of the divinity of the Logos, which is substantially joined to the humanity and dwells in it incarnate.”[14] Scheeben extends this line of thought by drawing out the Spirit-dimension of this anointing: the Holy Spirit, inasmuch as he proceeds from the Father through the Son, is sent down into the humanity joined to the Logos, since the Spirit himself is the perfume that gently radiates outward from the personal anointing that is the Logos, henceforward from his sacred humanity.[15] Moreover, this same divine unction (of the Logos and, at the same time, of the Spirit) is, by Scheeben’s reckoning, that which forms the basis of Christ’s priestly consecration. It is likewise, returning to our main theme, the heavenly altar fire that descends in and with the Logos and which renders him, on the level of his human existence, a sacrifice perfectly consecrated by this ennobling divine fire.[16] In other words: Christ, by his very constitution as God-man, is the Logos who—together with the Holy Spirit who is the fragrance suffusing outward from his sacrificial humanity—has taken human nature for himself from the stock of Israel. Therefore, this same Logos is God drawing near to Israel, God himself taking up abode in his temple, indeed God imparting himself by fire in a new and unexpected way.

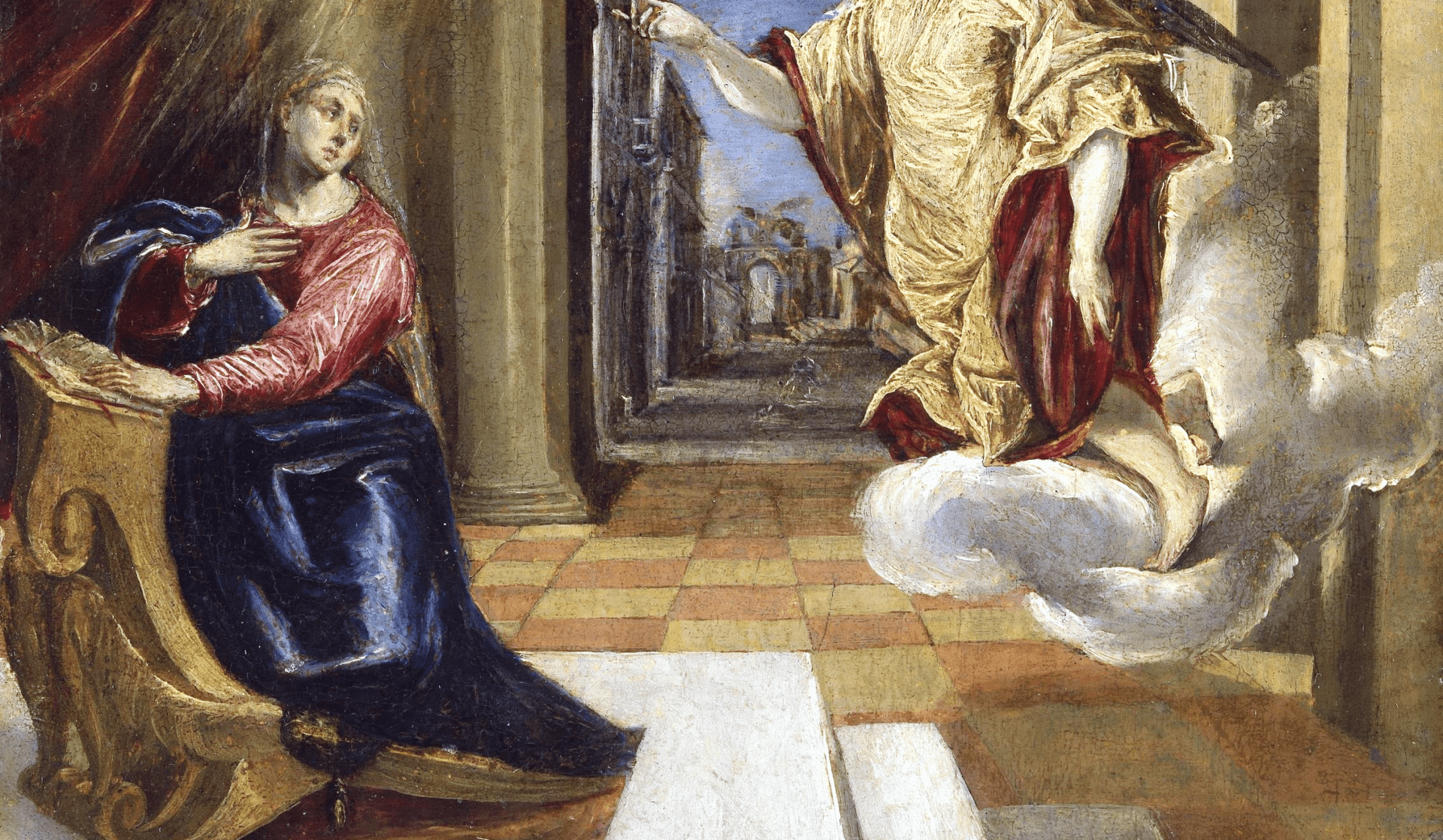

Scheeben brings out precisely this theme of Christ as temple in his commentary on Luke 1:31-37. There, focusing on Gabriel’s words to Mary at the Annunciation, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow [obumbrabit] you; therefore the child to be born will be called holy [sanctum]” (Lk 1:35), Scheeben comments: “Both the ‘Sanctum’ as well as the ‘obumbratio’ [overshadowing] [in the angel’s speech] contains an allusion to the descent of God in the cloud on the tabernacle, so as to rest within it on the Ark of the Covenant and thereby to make the tabernacle into the ‘Holy Place’ [Heiligen] par excellence.”[17] Thus, in Scheeben’s view, the divine descent upon Mary in the Incarnation serves as the fundamental New Testament fulfillment of the glory-cloud coming to rest on the tabernacle/temple in the Old Testament. Moreover, the type of the fire-cloud overshadowing the tabernacle contains an abiding reference to Christ on account of his personal constitution. Scheeben writes: “The Ark of the Covenant with the golden cover (the propitiatorium) and the cloud suspended upon it (the Schechinah or Chabod Adonai [the glory of the Lord]) were a highly significant type and symbol[18] of Christ and of God’s dwelling among men realized therein.”[19]

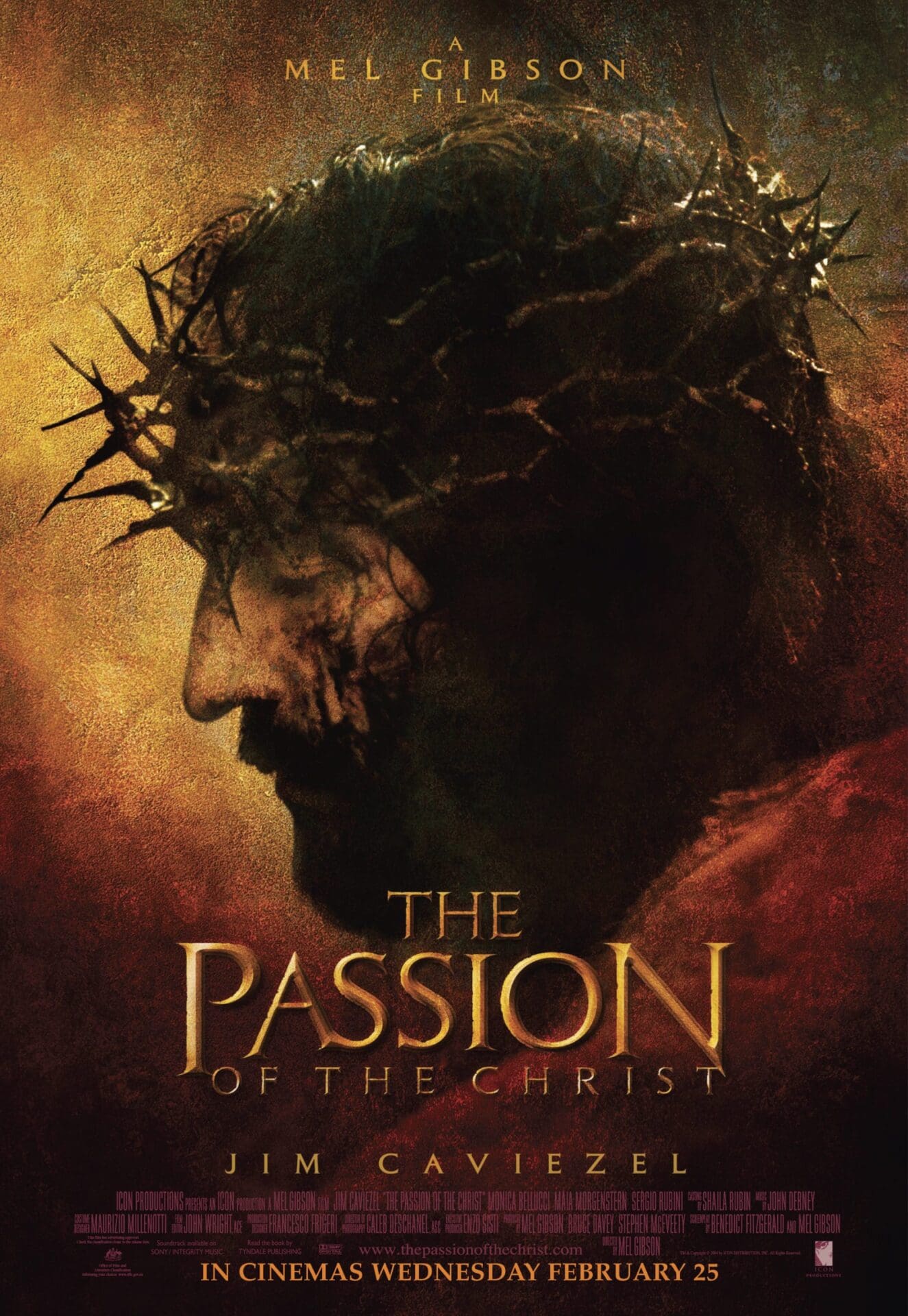

Now, as I argued above, along with the descent of the glory of YHWH at the end of exile, the Bible also holds out the prospect of the outpouring of a new altar fire accompanying and corresponding to the new appearance of God in the midst of his people. On the one hand, as briefly noted above, this has its counterpart in Scheeben in the descent of God’s glory in the Incarnation as it subsists in Christ’s personal existence as a human being (think of the “fire” in the exodus fire-cloud). However, the descending altar fire also has another fulfillment, this time found in Christ’s operation and personal history: it is the event in Christ’s life through which by his nature as God-man he becomes accessible to the rest of humanity by grace. Although Scheeben does not make the following connection explicit, I believe we can find clues to the location of this latter antitype in Scheeben’s writings by turning to his treatment of the eternal procession of the Holy Spirit.

As noted above, the Holy Spirit is, on Scheeben’s account, the fragrant aroma that wafts outward from the personal unction of the Logos anointing Christ’s humanity. The procession of the Holy Spirit from the Logos in salvation history is, however, the temporal counterpart to the Spirit’s eternal procession from Father and Son, but proximately from the Son. Now to what, let us ask, first, in the created order in general—and thereafter in Christ’s life (moving from type to antitype)—may we compare this relationship between Son and Spirit, that is, the production of a person other than by generation, necessary since the Spirit proceeds and is not begotten? According to Scheeben, only one such comparison is found: the production of Eve from sleeping Adam’s side in Gen 2:21-22.[20] Furthermore, there is also a correspondence between this creation narrative and a similar New Testament narrative: the piercing of Christ’s side and heart[21] while he slept the sleep of death on the Cross. It is in this sense that Methodius of Philippi calls the Holy Spirit the costa Verbi, the rib of the Word, but Scheeben thinks that “we shall do better to say that the Holy Spirit is sprung from the heart’s blood of the Father and the Son.”[22]

In other words, the outpouring of blood and water from Christ’s pierced side (which gives birth to the Church’s sacraments) expresses a parallel emission: the procession now become mission of the Holy Spirit from the Word. “The purifying and life-giving blood stream flowing from the heart of Christ over and into His Church,” Scheeben writes, “is at once the vehicle and the symbol of the temporal, and consequently of the eternal, outpouring of the Holy Spirit.”[23] Let us join this now to the fire typology: Scheeben throughout his writings depicts the Holy Spirit as fire, especially insofar as he is closely connected in Scripture and in the Patristic and theological tradition to the divine charity (Augustine’s igne amoris) that abides in our hearts (cf. Rom 5:5) and makes us a living sacrifice. Upon these grounds, Scheeben refers to the Holy Spirit poured out by Christ as “a spiritual river of fire [Feuerstrom] who does not merely wash and refresh souls [that is, in baptism], but at the same time transfigures and warms them.”[24]

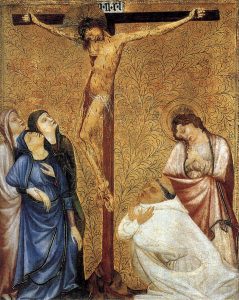

It follows that just as Christ is the fleshly temple and living pillar of cloud and fire that corresponds to the Old Testament types, so too the effusion of the blood and water from Christ’s side—which is Pentecost in nuce[25]—is the antitype to the event recorded in Leviticus 9:23-24, where fire came forth from before the Lord to consume and consecrate Israel’s sacrifices and, therein, the people themselves, so as to render them (and us!) a living temple and sacrifice of praise to the glory of God the Father. It is precisely this fire which brings about the true end of the exile and the definitive reconciliation of the people with God, for “now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ,” the two peoples having been made one, “a holy temple in the Lord,” fashioned into “a dwelling place of God in the Spirit” (Eph 2:13, 21-22).

Concluding Remarks

In dialogue with N. T. Wright, it has become clear that there existed the motif of the end of exile in the eschatology and worldview at the time of Second Temple Judaism; furthermore, there is also the prospect that Israel was still awaiting the return of the glory of YHWH to complete her repatriation from bondage. In connection with the return of the divine glory, however, one question remained. Will the related phenomenon of the descending divine fire return likewise? The New Testament outpouring of this divine fire from the glory of YHWH was to be found in the effusion of blood and water from Christ’s side, that is, in the Pentecostal outpouring of the divine fire of love, from its very wellspring, the pierced heart of the God-man in the mystery of his Passion. This is the mystery of Christ’s bride, the Church at its very source: the redeemed community, led out of exile and called to become a dwelling place “Holy to the Lord” (Ex 28:36), as she steps forth from the crucible of the burning love of Father and Son, herself enkindled and even set ablaze with this same divine love, that love through which she herself becomes a living holocaust, a living sacrifice of praise, who loves, as St. John says, by dint of the fact that “he first loved us” (1 Jn 4:19).

[1] David L. Augustine, “Sacrifice as Deification: Reflections on the Augustinian Foundations of Ratzinger’s Sacrificial Theology,” Adoremus Bulletin 22.1 (2016).

[2] My citation here of Isa 52:8 follows N. T. Wright’s use, employing the NRSV, but substituting “YHWH” for “Lord.”

[3] N. T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God [NTPG] (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1992), 268-69.

[4] Wright, NTPG, 269, emphasis added.

[5] See too N. T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God [JVG], Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996, 621: “But the geographical return from exile, when it came about under Cyrus and his successors, was not accompanied by any manifestations such as those in Exodus 40, Leviticus 9, 1 Kings 8, or even…Isaiah 6. Never do we hear that the pillar of cloud and fire which accompanied the Israelites in the wilderness has led the people back from their exile. At no point do we hear that YHWH has not gloriously returned to Zion. At no point is the house again filled with the cloud which veils his glory.”

[6] NTPG, 270.

[7] Nahum M. Sarna, The JPS Torah Commentary: Exodus (Philadelphia: JPS, 1991), 237. On the tabernacle as a mobile perpetuation of the Sinai experience, see L. Michael Morales, Who Shall Ascend the Mountain of the Lord?: A Biblical Theology of the Book of Leviticus (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 94, 96.

[8] All Scripture citations are Revised Standard Version, 2nd Catholic edition, unless otherwise indicated.

[9] Jonathan A. Goldstein, II Maccabees: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, The Anchor Bible 41A (New York: Doubleday, 1983), 173.

[10] Wright, JVG, 615.

[11] I say “relatively high” because Wright operates on the basis of what I consider to be a low view of Christ’s personal knowledge. Cf., for example, JVG, 606: “the Jesus we have described throughout must have had to wrestle [especially at Gethsemane] with the serious possibility that he might be totally deluded.”

[12] Cf. Matthias Joseph Scheeben, Handbuch der katholischen Dogmatik, V/2, 2nd ed., ed. Carl Feckes, in Gesammelte Schriften, VI/2 (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1954), n. 1478, where Scheeben describes Christ’s crucifixion “as a breaking that occurs, from without to without, by means of the expansive and diffusive force of Christ’s love and the penetration of the living vessel of his body via the streaming forth of his blood and his life.” (All translations of Scheeben’s Dogmatics are my own; all citations follow paragraph rather than page numbers.) For the anchoring of all of Christ’s created graces in the grace of union, i.e. in his unctio substantialis, see n. 910.

[13] Cf. esp. Matthias Joseph Scheeben, Handbuch der katholischen Dogmatik, V/1, 2nd ed., ed. Carl Feckes, in Gesammelte Schriften, VI/1 (Freiburg im Breisgau, Herder, 1954), n. 122: The man Jesus “is a substantially holy being [wesenhaft heiliges Wesen] and the true Son of God and therefore the promised Christ and Emmanuel and the true Lord of mankind.”

[14] Matthias Joseph Scheeben, The Mysteries of Christianity, trans. Cyril Vollert (St. Louis: Herder, 1954 [5th printing]), 332. He continues, on 333: “Accordingly ‘Christ’ and the ‘God-man’ mean one and the same thing.”

[15] See ibid. 332, emphases added: “When the Fathers say that Christ is anointed with the Holy Spirit, they mean that the Holy Spirit has descended into the humanity of Christ in the Logos from whom He proceeds, and that He anoints and perfumes the humanity as the distillation and fragrance of the ointment which is the Logos Himself.” Cf. this with Ps 23:5: “You anoint my head with oil, my cup overflows.”

[16] See Handbuch V/2, n. 1472.

[17] Scheeben, Handbuch V/1, n. 123.

[18] Lit: a “typical symbol [typisches Symbol].”

[19] Scheeben, Handbuch V/1, n. 81, emphases modified. See too n. 549. For the significance of the pillar of cloud and fire as representing the objective presence of God in the tabernacle in Scheeben, see Handbuch V/2, n. 1439: “The objective presence of God in the tabernacle was represented by the moving in ‘of the glory of God,’ i.e. the light-cloud [Lichtwolke], which had accompanied the people on their march through the wilderness and which corresponded to the manifestation of God on Sinai [i.e. the tabernacle was a mobile Sinai], which was also, however, in its own way, a dwelling of God and which the Jewish tradition as such called Schechinah.”

[20] For Scheeben’s whole discussion of this matter, see The Mysteries, “Appendix I to Part I: A Hypostatic Analogue in the Created Order for the Holy Spirit and His Origin,” 181-89. See too Matthias Joseph Scheeben, Handbuch der katholischen Dogmatik, II, 3rd ed., ed. Michael Schmaus, in Gesammelte Schriften, IV (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1948), nn. 1019-26.

[21] Scheeben holds that Christ’s side was pierced in such a way that his heart was pierced likewise, whether his chest was pierced on the left or trans-pierced from the right side. Cf. Handbuch V/2, n. 1206. On the rich significance of the piercing of Christ’ side in general, see n. 1205.

[22] Scheeben, The Mysteries, 185. See too 395: “The Holy Spirit is nothing less than the life-sap welling from the divine heart of the Logos, and His life-blood.”

[23] Ibid., 184. For the sacrificial significance of Jesus’ heart, see Handbuch V/1, n. 713: the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus is “the altar, on which the sacrificial fire burns, as well as the living organ of [Christ’s] priestly sacrificial disposition…. [it] is the most perfect symbol or sensible image of Christ’s sacrificial love.”

[24] Scheeben, Handbuch II, n. 1010. Cf. too Handbuch V/2, n. 1478, where Scheeben speaks of the “fire of the Holy Spirit” at work in Christ’s Resurrection and the Eucharistic consecration. Also note: with his reference to Holy Spirit as the “river of fire” above, Scheeben has merged the biblical typology of the sacrificial fire with that of the life-giving water pouring out of the temple (cf. Ezek 47:1; Rev 22:1, both read in light of Jn 7:38-39).

[25] I.e. insofar as the blood and water shed from Christ’s heart is the real-symbol of the eternal procession of the Holy Spirit from Father and Son become mission. On Pentecost, accordingly, the disciples enter into the mystery of the blood and water pouring forth from Christ’s side. This is the mystery of the Church at its fountainhead as it steps forth from the mystery of Christ’s Passion.