According to recent reports, Pope Francis has established a commission to review the translation principles and processes outlined in Liturgiam Authenticam. For some, the announcement is a reason to rejoice; for others, it is a cause for concern.

So much has, can, and will be asked about liturgical translations. Should they seek a more “dynamic” or “formal” equivalence? What degree of oversight ought local bishops’ conferences have, especially compared to that of the Holy See? How Latinate ought—or ought not—the final translations sound? Is the author of the liturgical lexicon—with its potential “dewfalls,” “consubstantials,” and “roofs”—adhering to the longer tradition or to the current culture? Add in all the linguistic “jots and tittles” (Matthew 5:18) and there is much to discuss.

But behind each debate surrounding “the smallest letter or the smallest part of a letter” (as another translation of Matthew 5:18 has it) appears a larger tension. This tension is just that—a pull, emphasis, or stress—between two necessary extremities: the traditional, universal, and unified, on the one hand, and the present, particular, and diverse, on the other.

To put the matter simply: should the style of liturgical language aspire toward elevation and transcendence, or ought it remain rooted in the human culture of any given time and place?

The immediate answer is that language ought not be either heavenly or earthly, but heavenly and earthly. To choose one or the other is—after the misfortune of some 5th century heretics—to become liturgical Nestorians overemphasizing the human, or linguistic Monophysites transcending out of this mundane world.

Liturgiam Authenticam itself desires to find a language among native tongues that justly satisfies both dimensions, as it begins: “The Second Vatican Council strongly desired to preserve with care the authentic Liturgy, which flows forth from the Church’s living and most ancient spiritual tradition, and to adapt it with pastoral wisdom to the genius of the various peoples” (n.1).

Still, within the limits of heaven and earth, is there a style of liturgical language that ought to characterize the praying Church?

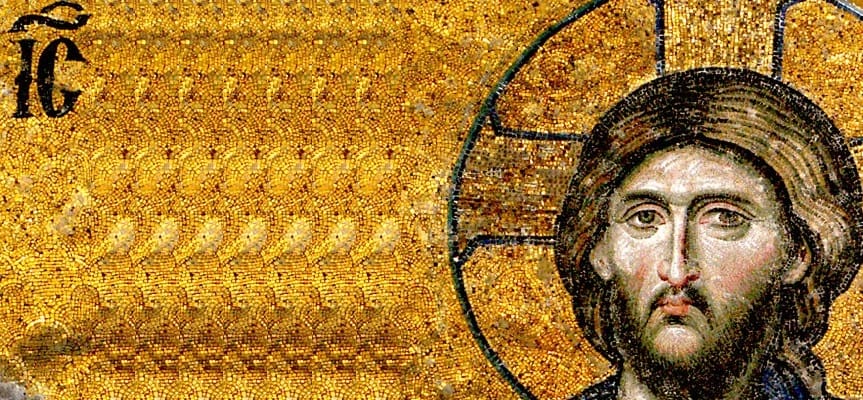

Romano Guardini’s The Spirit of the Liturgy devotes a chapter to “The Style of the Liturgy” which can equally shed light on the style of the liturgy’s language. Father Guardini takes as his norm Christ himself, the perfect embodiment of the “man of earth” and the “Man of heaven” (see Opening Prayer, option two, from Good Friday—in the present translation of the Missal). “Those who honestly want to come to grips with this problem [of liturgical style] in all its bearings should for their own guidance note the way in which the figure of Christ is represented” in both the Gospels and in the liturgy.

In the Gospels, “everything is alive; the reader breathes the air of earth; he sees Jesus of Nazareth walking about the streets and among the people, hears His incomparable and persuasive words, and is aware of the heart-to-heart intercourse between Jesus and His followers. The charm of vivid actuality pervades the historical portrait of Christ. He is so entirely one of us, a real person—Jesus, ‘the Carpenter’s Son’—Who lived in Nazareth in a certain street, wore certain clothes, and spoke in a certain manner.”

By extension, does not this Gospel account of Jesus describe liturgical language that is “about the streets and among the people,” a speech that is “entirely of us,” and our own “certain” culture?

“But how differently,” Guardini continues, “does the figure of Jesus appear in the liturgy! There He is the Sovereign Mediator between God and man, the eternal High-Priest, the divine Teacher, the Judge of the living and of the dead; in His Body, hidden in the Eucharist, He mystically unites all the faithful in the great society that is the Church; He is the God-Man, the Word that was made Flesh. The human element, or—involuntarily the theological expression rises to the lips—the Human Nature certainly remains intact, for the battle against Eutyches [and the Monophysites] was not fought in vain; He is truly and wholly human, with a body and soul which have actually lived. But they are now utterly transformed by the Godhead, rapt into the light of eternity, and remote from time and space. He is the Lord, ‘sitting at the right hand of the Father,’ the mystic Christ living on in His Church.”

Again, does not this depiction of Christ—the liturgical Word—characterize a liturgical prayer which is also “sovereign,” “eternal,” “divine,” “mystical,” and “transformed”? And it is precisely to these qualities of the liturgy’s style, and especially of its language, that some today object.

The same objections to “liturgical style” were present in Guardini’s own day: “It cannot be denied that great difficulties lie in the question of the adaptability of the liturgy to every individual, and more especially to the modern man. The latter wants to find in prayer—particularly if he is of an independent turn of mind—the direct expression of his spiritual condition. Yet in the liturgy he is expected to accept, as the mouthpiece of his inner life, a system of ideas, prayer and action, which is too highly generalized, and, as it were, unsuited to him. It strikes him as being formal and almost meaningless. He is especially sensible of this when he compares the liturgy with the natural outpourings of spontaneous prayer. Liturgical formulas, unlike the language of a person who is spiritually congenial, are not to be grasped straightway without any further mental exertion on the listener’s part…. These clear-cut formulas are liable to grate more particularly upon the modern man, so intensely sensitive in everything which affects his scheme of life, who looks for a touch of nature everywhere and listens so attentively for the personal note. He easily tends to consider the idiom of the liturgy as artificial, and its ritual as purely formal.”

Here, Romano Guardini addresses that most fundamental of misconceptions underlying the current debate surrounding liturgical translations: namely, that language of an elevated, poetic, traditional, transcendent, and particularly theological character has little place in the liturgy. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Pope Francis, who has cited Romano Guardini in the Encyclicals Lumen Fidei and Laudato Si, as well as the exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, must be familiar with The Spirit of the Liturgy and its place in the 20th Century liturgical movement. Indeed, as the work celebrates 100 years in 2018, we hope the commission reviewing Liturgiam Authenticam will let it continue to influence the ongoing liturgical renewal of the 21st century.

If Guardini is to be believed—or, rather, the weight of his thinking is to be found true—then we would do well to heed his conclusion that a “vital, clear, and universally comprehensible” style is the only liturgical style possible.