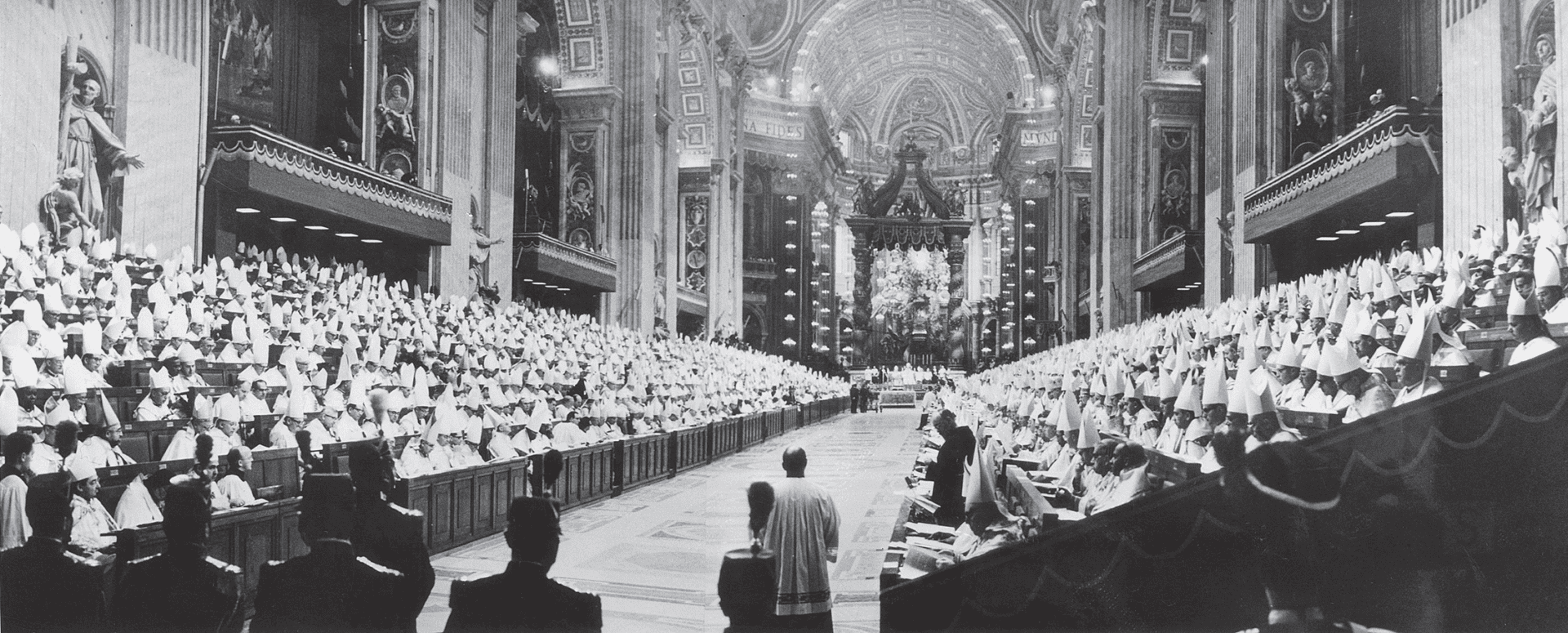

December 8, 2015, marks 50 years since the close of the Second Vatican Council. The day before the Council’s end in 1965, Pope Paul VI promulgated the Council’s final two (of sixteen) documents, Dignitatis Humanae, on religious freedom, and Gaudium et Spes, meaning “joy and hope,” the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World.

Much as its first document has had longstanding impact, so too has the Council’s last. In what is perhaps the Council’s most memorable line, the Fathers teach in Gaudium et Spes that “only in the mystery of the incarnate Word does the mystery of man take on light…. Christ, the final Adam, by the revelation of the mystery of the Father and his love, fully reveals man to man himself and makes his supreme calling clear” (n.22).

In his first Encyclical, Redemptor Hominis, Pope Saint John Paul II called this passage a “stupendous text.” After contributing to the preparation of Gaudium et Spes as an auxiliary bishop of Krakow, much of his papacy would direct our gaze toward the face of Jesus so that we could learn from him not simply who God was, but who we ourselves are called to be now and forever, how to find joy in the present life while hoping for eternal life with God.

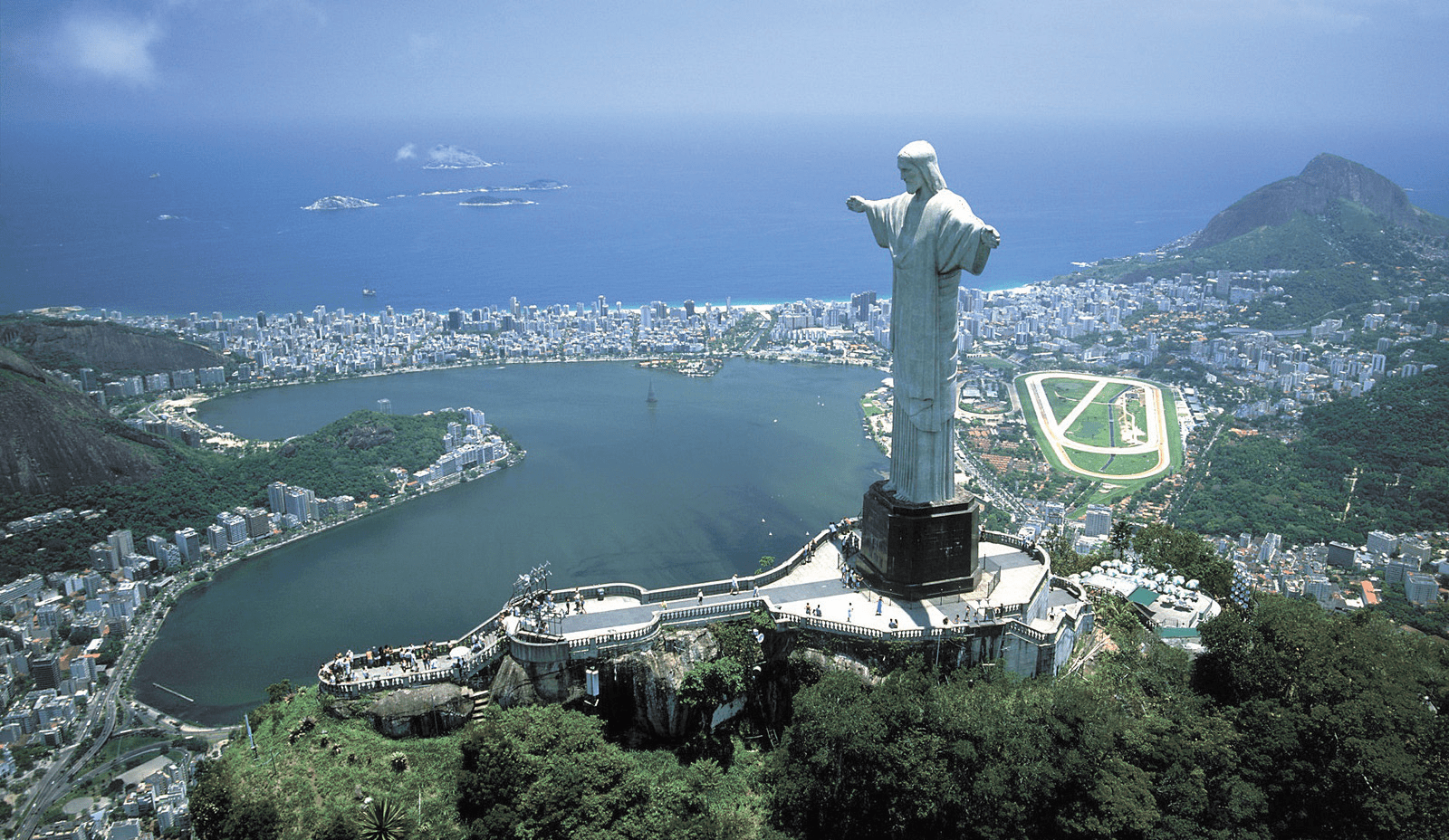

As the Council explained, and the saintly Pope related, “by his incarnation the Son of God has united himself in some fashion with every man. He worked with human hands, he thought with a human mind, acted by human choice and loved with a human heart.” The God who was man showed the value of the unborn and of the child; the necessity of father and mother and family life; the goodness of labor; the call to serve and teach and pray; the merits of suffering; and the path to eternity for which we hope. Our Redeemer’s humanity gives example for our humanity now. And like Christ, our faith and its practice have implications not simply for the world to come but in the world at hand: it is eminently human, giving joy to everyday life.

Central to this endeavor both here and hereafter, the Catholic liturgy is a source of joy and hope, for its substance is the God-made-man, Christ who not only reveals God to man but reveals “man to man himself.” Liturgical scholar Louis Bouyer warned of both “Nestorian and Monophysite liturgies.” He meant that the errors that befell our understanding of Christ— emphasizing his humanity to the detriment of his divinity, as the fifth-century bishop Nestorius had done; or elevating Jesus’ divinity to the diminution of his humanity, as Eutyches and the Monophysites had done—are also dangers for liturgical practice and understanding.

The liturgy, like the incarnate Christ, does and must use human, natural things: bread, water, human speech, doors, music, and marriage bonds. But the Church and her liturgy don’t simply keep these elements on their natural plane but elevate them to a supernatural end: man’s bread becomes the panis angelicus; natural washing effects supernatural cleansing; human communication enters a divine dialogue. By using ordinary things in an extraordinary way, Christ the High Priest of the liturgy reveals to us our humanity and our divine calling.

The topics treated in the present issue can similarly be seen through the lenses of Christ, human and divine. In preparation for the forthcoming second edition of the Rite of Marriage, Father Randy Stice clarifies some aspects of the Church’s traditional theology of marriage. Still, as sacramental marriage does have a divine dimension, matrimony “has this specific element that distinguishes it from all the other sacraments: it is the sacrament of something that was part of the very economy of creation” (citing St. John Paul II).

In addition to December 8 marking 50 years since the Council’s close— about which the Liturgical Institute’s Father Douglas Martis offers his thoughts in this issue—the day also inaugurates the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy called by Pope Francis. A key element marking its opening, both in Rome and throughout the world, is the opening of a Holy Door. While a door is most obviously a human creation, Monsignor Robert Dempsey explains how the Church sees the Holy Door as equally divine—if for no other reason than Christ calls himself “the door” (John 10:9)—and how natural passage through the Door of Mercy should be a prayer and a revelation of Jesus Christ, who is “the face of the Father’s mercy” (Pope Francis).

These liturgical elements, and others, when celebrated and seen correctly, are a source of joy and hope in this modern world, for they are encounters with Christ who “fully reveals man to man himself and makes his supreme calling clear” (n.22).