By Father Douglas Martis

Introduction

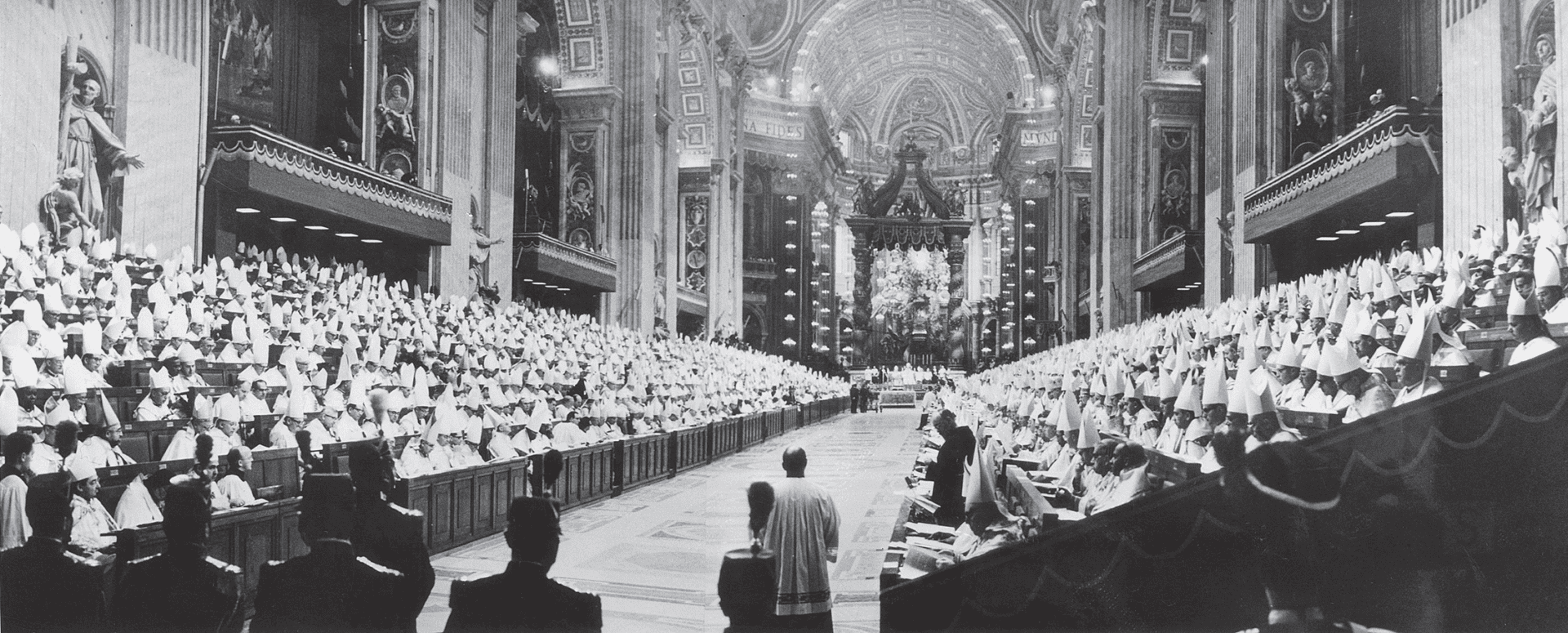

When the Second Vatican Council closed its doors on December 8, 1965, it had bequeathed to the Church a textual monument that has been a steady source of teaching, inspiration, and debate. The sixteen documents promulgated by the Fathers of the Council include nine decrees, three declarations and four constitutions. Each category of document carries its own magisterial weight. The most significant are the constitutions on the liturgy, the Church in se, divine revelation, and the Church in relation to the world. Each has had its own significant impact on the postconciliar Church. On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the conclusion of the ecumenical council, it is opportune to consider their broad impact, in particular in relation to the Church’s public prayer.

The dreamer sees only the good; the cynic revels in highlighting the bad. We will emulate the realist who tries to recognize in this marvelously mixed and often mixed up world different expressions, competing visions, and various values in tension.

We will consider each of these conciliar documents from three perspectives: first, noting the grace, i.e., the significant contribution that each has made to the renewal of the Church, particularly from the liturgical perspective; second, pointing out the danger that has become salient in the lived experience of the Church since 1965; and finally, offering a particular challenge engendered by each constitution as the Church continues to draw from the teaching of the Second Vatican Council.

Fifty years is not much time in the history of the Church, and although the great event of the Twenty-first Ecumenical Council can sound like ancient history to Gen X and Millennials (such as those whom I have been teaching and forming at Mundelein Seminary since 2002), half a century is not enough distance to be able to fully and accurately evaluate the Council’s value. We revisit these documents not to ascribe “good” or “bad,” but to consider what we have yet to learn, what insight there is to gain, what inspiration has yet to be derived from the event, the phenomenon and the teaching the Council has offered. Undoubtedly advances in technology, social change, upheaval between nations, setbacks and progress in medicine, and the pace of the modern world have all changed the landscape in which the principal themes of the Council unfolded. But timeless truths always emerge as perennial remedies for the world’s ills.

Let us not miss the opportunity to note that the Church does not treat the documents of the Second Vatican Council as a mere chronicle of a debate to be catalogue and shelved, as the forgotten work of bureaucrats only to be discovered with cries of “Eureka” by nerdy doctoral students in some musty Vatican basement centuries hence. As she had done with other texts of the tradition, the Church has woven the principal themes contained in these four constitutions into her liturgical prayer, in particular the Liturgy of Hours. They continue to instruct and inform both prayer and action in the world.

Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy The fact that the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, was the first document to be produced by the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council (December 4, 1963), should not be interpreted to mean merely that the Fathers considered the liturgy to be “most important.” It was also due to the fact that the study group was prepared to produce such a document.

The liturgical movement had been underway for nearly two generations; liturgical renewal had been going on for decades. Pope Leo XIII had already called attention to participation in the Mass, referring to it in Mirae caritatis (1902) as the “font and most important gift.” Even the classic liturgical battle cry, “active participation,” had already passed its sixtieth birthday by the time it was redacted into paragraph 14 of the Constitution. Nor must we forget that that term, coined by Pius X to insist on the restoration of Gregorian chant, had been reiterated by Saint Pius’ successors. In Divini Cultus (1928), Pope Pius XI echoes his predecessor’s claim saying

…so that the faithful take a more active part in divine worship, let Gregorian chant be restored to popular use in the parts proper to the people. Indeed it is very necessary that the faithful attend the sacred ceremonies not as if they were outsiders or mute onlookers, but let them fully appreciate the beauty of the liturgy and take part in the sacred ceremonies, alternating their voices with the priest and the choir, according to the prescribed norms. (DC 9)

Just fifteen years before the opening of the Council, Pope Pius XII in Mediator Dei reminds the Church of the importance of the Eucharist in the life of the Faithful.

Through this active and individual participation, the members of the Mystical Body not only become daily more like to their divine Head, but the life flowing from the Head is imparted to the members, so that we can each repeat the words of St. Paul, “With Christ I am nailed to the cross: I live, now not I, but Christ live in me.” (MD 78)

The call of Sacrosanctum Concilium for a participation that is not only active, but also full and conscious, represents a honing of the Magisterium’s teaching.

In this context we can see the overwhelming grace offered by the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. It articulates not only a “program” for renewal but also put language to a movement that was well underway. The perception by some that liturgical changes in the years after the Council were drastic and rapid puts us at risk of forgetting the decades-long desire, repeated by every pontiff since 1903, for a more complete engagement of the faithful in the source and summit (fons et culmens) of the Christian life. The noble desire of these liturgical leaders was the opening of the riches of the sacred liturgy so that the people could benefit more fully from the graces to be given. It is a conviction we would do well to retrieve today. There is still much to be learned from study of the teaching of the Church, the research of scholars, and the efforts of pastors in the years leading up to the Council. Their desire that knowledge of the liturgy should not be the domain of an academic, or even pastoral, elite should motivate us today to facilitate access to the divine mysteries.

Despite progress made in liturgical renewal (liturgical reform is a separate question), several dangers exist. The widespread use of the vernacular has no doubt been of tremendous benefit, but where it has led to a contempt for the Latin language, some serious examination of conscience must be done. In the new global dynamic that fosters a growing appreciation of the contributions of different cultures and languages, the liturgical language of the Church must be recognized as an important, even essential, part of our cultural heritage. Vernacular expression can aid liturgical comprehension, but it cannot replace much needed and necessary liturgical catechesis.

Continuing liturgical renewal must face the challenge of presenting the fullness of Catholic spirituality, emphasizing the Church’s official public forms of prayer, including the Divine Office, without compromising forms of personal prayer and private devotion. Authentic public prayer is predicated on a life of consistent personal prayer. Only when this is better understood can the spectrum of prayer be mutually enriching.

Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Genuine liturgical participation is grounded in the dyad of internal awareness and external expression. In like manner, the Second Vatican Council’s ecclesiological understanding treats the Church in se and ad extra. The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium (November 21, 1964), represents a sustained reflection on the nature of the Church, as she is in herself. The grace of this text can be described as a growing self-awareness on the part of the faithful that they belong to a dynamic, living, growing organism.

Chapter Two of Lumen Gentium is especially important in that it retrieves the notion of “People of God,” called by God into an assembly. This assembly is, in essence, a liturgical assembly: the people are called and united for the purpose of praising of God. This view emphasizes the divine initiative—it is God who calls, God’s voice which transforms individuals into a people. It highlights our connection as the new Israel with Israel of the alliance of old. It articulates the role of this People vis-àvis the world, that is, our responsibility to give witness to the mystery of the Gospel. It draws from the fountain of scripture, grounding its teaching fundamentally in the insight of the New Testament, especially I Peter 2:9, “You are a royal priesthood,” echoed constantly in the liturgical texts.

The danger with such an emphasis is that—while the Constitution itself does not do this—it can lead to the diminishment of other significant, evocative images of the Church. Lumen Gentium speaks of the Church also as the Body of Christ, as Spouse and Mother, as sheepfold, gateway, as God’s building and as the “Jerusalem which is above.” Coupled with the social upheaval of the 1960s, in some places the notion that the Church is “People of God” resulted in an anticlericalism, a kind of rejection of the Church as institution. One would hear “We are the Church,” that we are a self-determining People. This is religion as revolution, rather than as call to conversion. There can be a temptation to forget Chapter Three of Lumen Gentium which describes the hierarchical nature of the Church with its “variety of offices which aim at the good of the whole body” (LG 18).

The challenge for us today it to embrace the well-founded image, without turning it into an idol; to reap the good fruit that the image bears without yielding to the temptation to fashion it according to contemporary political agendas.

The remedy is given by the Constitution itself: recognize the preeminence of Christ.

Christ, the one Mediator, established and continually sustains here on earth his holy Church, the community of faith, hope and charity, as an entity with visible delineation through which he communicated truth and grace to all. But, the society structured with hierarchical organs and the Mystical Body of Christ, are not to be considered as two realities, nor are the visible assembly and the spiritual community, nor the earthly Church and the Church enriched with heavenly things; rather they form one complex reality which coalesces from a divine and a human element. For this reason, by no weak analogy, it is compared to the mystery of the incarnate Word. As the assumed nature, inseparably united to him, serves the divine Word as a living organ of salvation, so, in a similar way, does the visible social structure of the Church serve the Spirit of Christ, who vivifies it, in the building up of the body. (LG 8)

Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation The Church expresses unequivocally her appreciation for sacred scripture. The richness of the “fare” is perhaps one of the most salient experiences of the Council’s liturgical reform. The availability of the texts of the Bible in the vernacular is likewise a particular concern of the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum (November 28, 1965).

Easy access to Sacred Scripture should be provided for all the Christian faithful. That is why the Church from the very beginning accepted as her own that very ancient Greek translation of the Old Testament which is called the septuagint; and she has always given a place of honor to other Eastern translations and Latin ones, especially the Latin translation known as the vulgate. But since the word of God should be accessible at all times, the Church by her authority and with maternal concern sees to it that suitable and correct translations are made into different languages, especially from the original texts of the sacred books. And should the opportunity arise and the Church authorities approve, if these translations are produced in cooperation with the separated brethren as well, all Christians will be able to use them. (DV 22)

In some ways, Sacrosanctum Concilium had already expressed the Church’s commitment to the Word of God: The treasures of the bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God’s word. In this way a more representative portion of the holy scriptures will be read to the people in the course of a prescribed number of years. (SC 51)

Certainly Catholics are more aware of the biblical basis of the Mass; certainly they benefit today from a wider use of the vernacular. The Church is less susceptible to the anecdotal critique that “Catholics don’t believe in the Bible.”

The Church has always venerated the divine Scriptures just as she venerates the body of the Lord, since, especially in the sacred liturgy, she unceasingly receives and offers to the faithful the bread of life from the table both of God’s word and of Christ’s body. (Dei Verbum 21)

But by a strange and ironic convergence, the Council’s call for better access to scripture in the liturgy coincided with the near-annihilation of the scripturally- based antiphons of the Mass. Musicians and composers seemed to be unaware of the teaching of Musicam Sacram (1967) that called for the singing before anything else of the Order of Mass and promoted the chanting of the Entrance, Offertory and Communion antiphons. Even though this teaching was clearly grounded in Sacrosanctum Concilium and honored Pius X’s insistence that one “sing the Mass,” contemporary music has emphasized hymnody and newly composed songs.

Energies were spent on compositions that downplayed the scriptural foundations of the Eucharistic liturgy. Even the early work of groups like the St. Louis Jesuits which made some effort to use scriptural texts in their modern compositions eventually dissembled into the admission of nearly any text intended to express a religious sentiment.

The great danger was that for the sake of being relevant, the new composition created more distance between the Mass and the scriptures, and has shifted people’s expectations of the purpose of sacred music. Perhaps the argument can be made that before the liturgical reform more scripture was included in the Mass.

The challenge for the future will be to honor the sacred text in the way envisioned by the Church and to see its musical expression not as a quaint addition, but as integral to the liturgical act.

Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the World of Today

The fourth constitution promulgated by the Second Vatican Council was in some ways the Council’s final word to the world. The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, Gaudium et spes (December 7, 1965), reveals in the document’s opening words the stance of the Church toward the world as envisaged by the Fathers of the Council. Clothing its sentiment in the virtues of hope and joy, it expresses in a positive light the relationship between Church and world. It balances new discoveries of science with the profound, enduring truth of religion.

The pioneers of the liturgical movement, too, knew that prayer and action in the world go hand in hand. In Gaudium et spes the Church and the world are not an adversarial relationship in which each is suspicious of the other, but rather the document expresses the clear conviction that the Church has the answer to the difficulties and challenges posed by the world of today.

Today, the human race is involved in a new stage of history. Profound and rapid changes are spreading by degrees around the whole world. Triggered by the intelligence and creative energies of man, these changes recoil upon him, upon his decisions and desires, both individual and collective, and upon his manner of thinking and acting with respect to things and to people. Hence we can already speak of a true cultural and social transformation, one which has repercussions on man’s religious life as well. (GS 4)

Herein lies the modern dilemma.

Since all these things are so, the modern world shows itself at once powerful and weak, capable of the noblest deeds or the foulest; before it lies the path to freedom or to slavery, to progress or retreat, to brotherhood or hatred. Moreover, man is becoming aware that it is his responsibility to guide aright the forces which he has unleashed and which can enslave him or minister to him. That is why he is putting questions to himself. (GS 9)

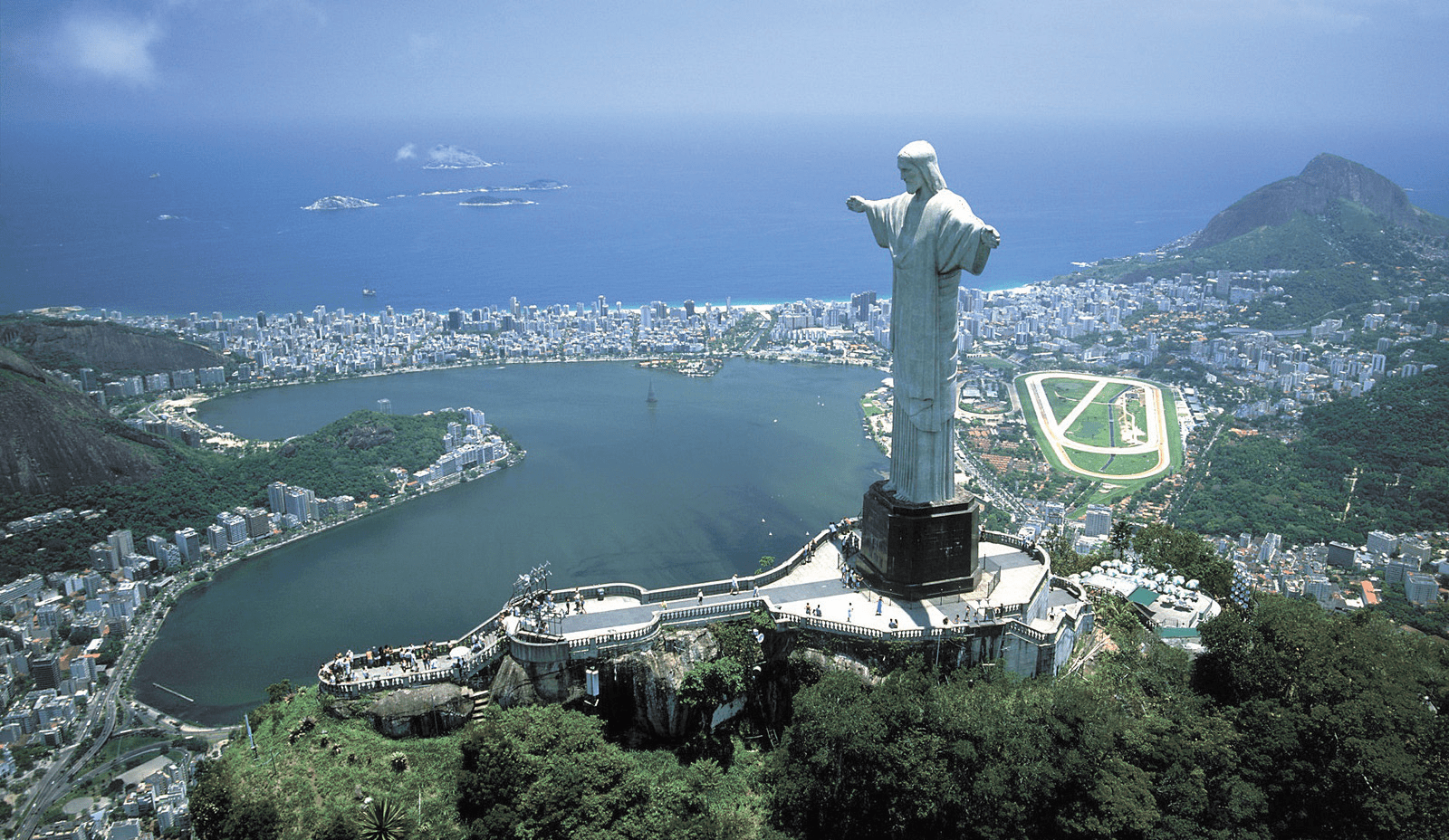

Created by God, destined for eternity, man’s virtue of religion links him in “this earthly exile” with the power of the divine. The Pastoral Constitution suggests that the Church has the answer to the world’s deepest questions. The Church must present Christ to our time if she is to fulfill her mission in the world.

The Church thus proposes a kind of accompaniment with the world: to walk along with it and reveal by its witness of evangelization the beauty of the Christian faith. The Church, then, is a As an auxiliary bishop of Karakow, Poland, Karol Wojtyla attended sessions of the Council and was involved in developing the text of Gaudium et Spes. He would say later, “The great intimate knowledge of the genesis of Gaudium et Spes enabled me to appreciate in great depth the prophetic value and to widely undertake the contents in my Magisterium from the first Encyclical, Redemptor hominis.” mentor, a companion, a guide through the dangers of this world, always pointing to that New World, prepared by Divine Providence and proclaimed by the gospel of Christ.

As the years have gone by, the risks have become evident. Unless they remain grounded in the truth, mentors have the danger of falling into same trap as those they are trying to help. If we neglect in our preaching the constant reminder of the afterlife, if we give the impression that here is all there is, social justice becomes only social work. Disconnected from the larger mystery of salvation, medicine becomes a matter of self-determination rather than a witness to trust in the mercy of God. There is a persistent danger in walking lockstep with the world. That is the temptation to forget that we are destined for another world, to forget that here is not the end. The risk in meeting people “where they are at” is that we can easily forget the call to conversion and instead simply endorse the status quo.

If the Church will be faithful to her mission and responsive to the call of the Second Vatican Council, she will both accompany people on their journey and remind them of their heavenly homeland. She will manifest God’s love to the world, but also call it to conversion, preparing it for God’s work of a new heavens and a new earth.

Engage

The Fathers of the Second Vatican Council, in their writings, especially the dogmatic and pastoral constitutions on the nature of the Church and the constitutions on Divine Revelation and Sacred Liturgy, offer a challenge to the world today to be engaged in the Church’s prayer and in her witness and action in the world. As with the legacies of previous councils, the course charted by Vatican II continues to articulate the teaching of the Church and shape the way her faith will be expressed to future generations.

Father Douglas Martis is a priest of the Diocese of Joliet-in-Illinois. He holds doctoral degrees in Sacred Theology and History of Religions and Religious Anthropology. He is professor of Sacramental Theology at the University of St. Mary of the Lake where he also directs the Liturgical Institute.